BettyCrocker.com

Elizabeth A. Blake, Clark UniversityThough she celebrates her 100th birthday this year, Betty Crocker was never born. Nor does she ever really age.

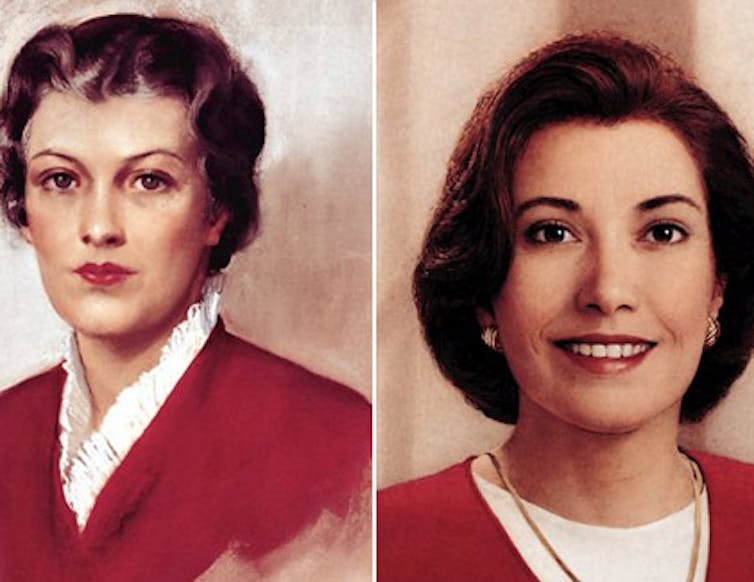

When her face did change over the past century, it was because it had been reinterpreted by artists and shaped by algorithms.

Betty’s most recent official portrait – painted in 1996 to celebrate her 75th birthday – was inspired by a composite photograph, itself based on photographs of 75 real women reflecting the spirit of Betty Crocker and the changing demographics of America. In it, she doesn’t look a day over 40.

More importantly, this painting captures something that has always been true about Betty Crocker: She represents a cultural ideal rather than an actual woman.

Nevertheless, women often wrote to Betty Crocker and saved the letters they received in return. Many of them debated whether or not she was, in fact, a real person.

In my academic research on cookbooks, I focus primarily on the way cookbook authors, mostly women, have used the cookbook as a space to explore politics and aesthetics while fostering a sense of community among readers.

But what does it mean when a cookbook author isn’t a real person?

Inventing Betty

From the very beginning, Betty Crocker emerged in response to the needs of the masses.

In 1921, readers of the Saturday Evening Post were invited by the Washburn Crosby Co. – the parent company of Gold Medal Flour – to complete a jigsaw puzzle and mail it in for a prize. The advertising department got more than it expected.

In addition to contest entries, customers were sending in questions, asking for cooking advice. Betty’s name was invented as a customer service tool so that the return letters the company’s mostly male advertising department sent in response to these queries would seem more personal. It also seemed more likely that their mostly female customers would trust a woman.

“Betty” was chosen because it seemed friendly and familiar, while “Crocker” honored a former executive with that last name. Her signature came next, chosen from among an assortment submitted by female employees.

As Betty became a household name, the fictional cook and homemaker received so many letters that other employees had to be trained to reproduce that familiar signature.

The advertising department chose the signature for its distinctiveness, though its quirks and contours have been smoothed out over time, so much so that the version that appears on today’s boxes is hardly recognizable. Like Betty’s face, which was first painted in 1936, her signature has evolved with the times.

Betty eventually became a cultural juggernaut – a media personality, with a radio show and a vast library of publications to her name.

An outlier in cookbook culture

As I explain to students in my food and literature courses, cookbooks aren’t valued solely for the quality of their recipes. Cookbooks use the literary techniques of characterization and narrative to invite readers into imagined worlds.

Deb Lindsey For The Washington Post via Getty Images

By their very nature, recipes are forward-looking; they anticipate a future in which you’ve cooked something delicious. But, as they appear in many cookbooks – and in plenty of home recipe boxes – recipes also reflect a fondly remembered past. Notes in the margin of a recipe card or splatters on a cookbook page may remind us of the times a beloved recipe was cooked and eaten. A recipe may have the name of a family member attached, or even be in their handwriting.

When cookbooks include personal anecdotes, they invite a feeling of connection by mimicking the personal history that is collected in a recipe box.

Irma Rombauer may have perfected this style in her 1931 book “The Joy of Cooking,” but she didn’t invent it. American publishers started printing cookbooks in the middle of the 18th century, and even the genre’s earliest authors had a sense of the power of character, just as many food bloggers do today.

An American ideal

But because Betty Crocker’s cookbooks were written by committee, with recipes tested by staffers and home cooks, that personal history isn’t quite so personal.

As one ad for the “Betty Crocker Picture Cook Book” put it, “The women of America helped Betty Crocker write the Picture Cook Book,” and the resulting book “reflected the warmth and personality of the American home.” And while books like “Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book” open with a friendly note signed by the fictional homemaker herself, the recipe headnotes carefully avoid the pretense that she is a real person, giving credit instead to the women who submitted the recipes, suggesting variations or providing historical context.

Hathi Trust Digital Library

Betty Crocker’s books invited American women to imagine themselves as part of a community connected by the loose bond of shared recipes. And because they don’t express the unique tastes of a particular person, Betty Crocker books instead promote taste as a shared cultural experience common to all American families, and cooking as a skill to which all women should aspire.

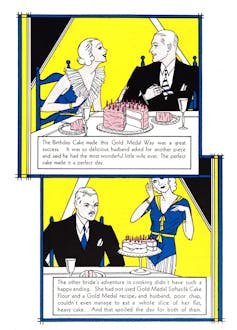

The “Story of Two Brides” that appears in Betty Crocker’s 1933 pamphlet “New Party Cakes for all Occasions” contrasts the good “little bride” who “has been taking radio cooking lessons from Betty Crocker” with the hapless “other bride” whose cooking and shopping habits are equally careless. The message here isn’t particularly subtle: The trick to becoming “the most wonderful little wife ever” is baking well, and buying the right flour.

Betty today

Despite its charming illustrations, the retrograde attitude of that 1933 pamphlet probably wouldn’t sell very many cookbooks today, let alone baking mixes, kitchen appliances or any of the other products that now bear the Betty Crocker brand, which General Mills now owns.

But if Betty Crocker’s branding in the supermarket is all about convenience and ease, the retro stylings of her newest cookbooks are a reminder that her brand is also a nostalgic one.

Published this year, for her 100th anniversary, the “Betty Crocker Best 100” reprints all of Betty’s portraits and tells the story of her invention. Rather than using the logo that appears on contemporary products, the front cover returns to the quirkier script of the early Betty, and the “personal” note at the opening of the book reminds readers that “it’s always been about recognizing that the kitchen is at the heart of the home.”

As Betty is continually reinvented in response to America’s evolving sense of self, perhaps this means valuing domestic labor without judging women by the quality of their cakes, and building community between all bakers – even those who won’t ever be good little brides.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Elizabeth A. Blake, Assistant Professor of English, Clark University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.