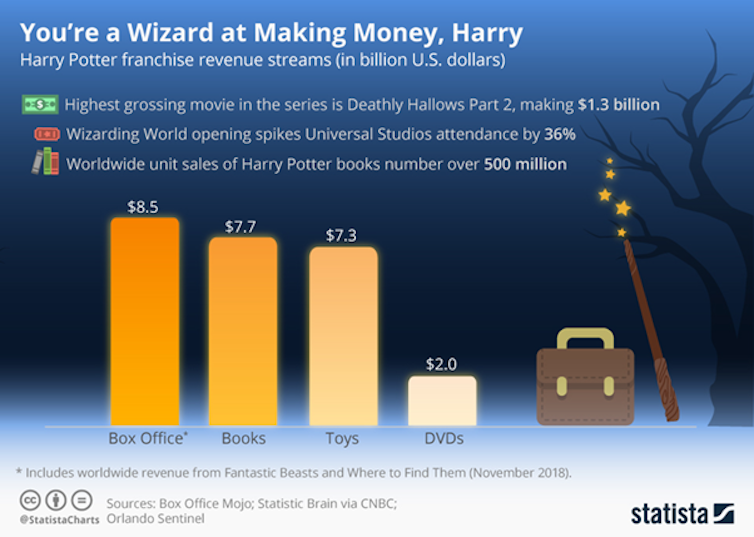

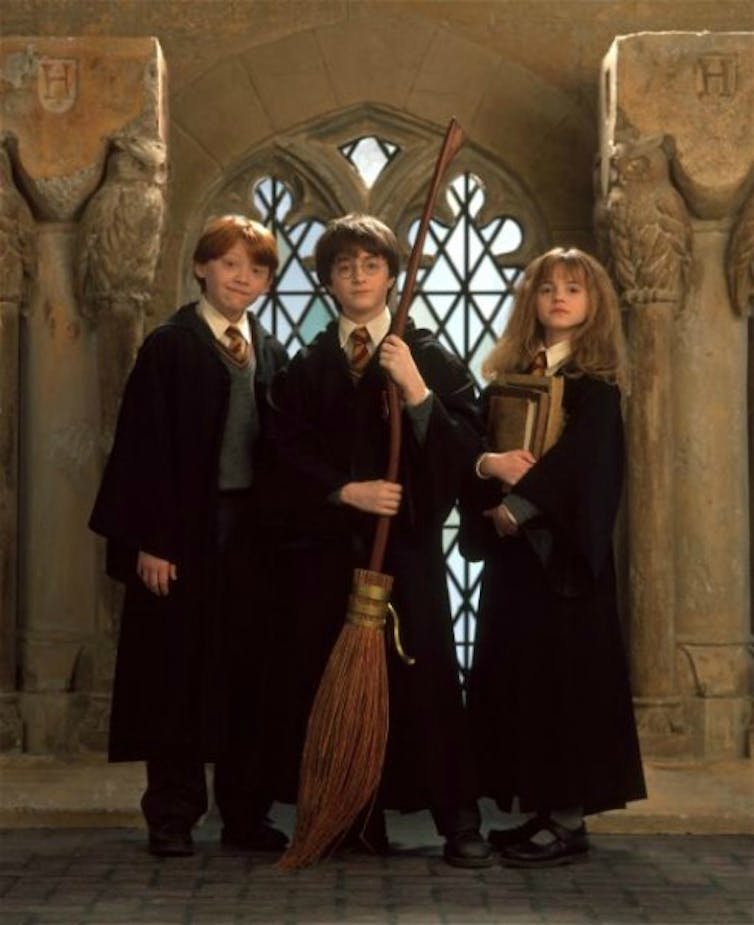

Jane Sunderland, Lancaster UniversityHarry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first film in the eight-part series, has reached its 20th anniversary. Released in 2001, it became the highest-grossing film of that year and the second-highest-grossing ever at the time (it’s now number 76). The film follows Harry’s first year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry as he begins his formal wizarding education.

The first film in the series came four years after the first book (of the same name) in JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series, which is 25 years old next year. Gone, of course, are the heady days when children grew up alongside Harry Potter, queuing outside bookshops the night before the one-minute-past-midnight release of the next volume in the series.

But this enthusiasm gave rise to a very particular phenomenon, with suggestions that the Harry Potter series prompted previously reluctant readers – in particular boys – to read fiction. Indeed, massive book sales led to media declarations of dramatic changes in children’s attitudes to reading.

While this claim does have some substance, the phenomenon was not quite as suggested. Parents and grandparents often bought Harry Potter books for their children, unasked. And while many children watched the films, they did not read the books.

That said, of couse, many children did read them. And while some young purists post-2001 refused to watch the first film until they had read the book, it’s likely the films prompted other children to then go on to read the books.

In our own 2014 study of around 600 British primary and secondary school students, around half reported having read at least one of the books, and more of these readers were boys. The most likely number of books in the series to have been read was all seven – the second likeliest, just one.

A substantial minority of children clearly engaged hugely with the series as readers – and it can only be assumed this benefited their reading more generally. This level of engagement was partly because it was a series, bringing with it a sense of continuity and achievement.

Neither were enthusiasts put off by the sheer length of the later books. Indeed, this may have added to children’s enjoyment and sense of achievement. As Rowling herself has said, “When I was a child, if I was enjoying a book, I didn’t want to finish it.”

The boy who lived on?

While the films are frequently televised, and with news that Warner Bros is planning to develop a television series set in the wizarding world, the Harry Potter books no longer top the best-selling children’s book lists. After 24 years, Amazon however still ranks the Philosopher’s Stone at number ten in their list of best-selling children’s books, with the others in the series not far behind.

All this is not surprising. Harry Potter is both enduringly imaginative – the spells, the magic, the different creatures – and reassuringly familiar – basically, it’s a school story. It has memorable, appealing characters and the style is undemanding. And now, a new generation of young parents who grew up with Harry Potter may want their children to have their own Potter experience. Though it seems likely that more children will continue to watch the films than read the books.

However, Harry Potter has come in for criticism in more recent years. Many readers today may be more aware of the elitism of Hogwarts. There is an imbalance between the number of male and female characters in the series, especially teachers. Its racial diversity has been accused of being tokenistic. And it lacks even hints of LGBTQ+ characters. Rowling’s claim in 2007 that she thought of Dumbledore as gay is not even suggested in the books.

Rowling herself has also generated controversy through her comments about gender and sex in relation to the debate around transgender rights, first on Twitter and later in a 3,700-word essay in 2020.

Yet Harry Potter is far from alone in the canon of consistently popular children’s literature when it comes to most of these issues. And none of them appear to have affected book sales so far.

It remains to be seen whether such issues will discourage millennial parents from introducing Harry Potter to their own children or affect its popularity among future generations. And in this sense, only time will tell if the appeal of the books and the films will continue to endure.![]()

Jane Sunderland, Honorary Reader in English, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.