The link below is to an article that looks at how to reduce the environmental toll of paper in publishing.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/environmental-toll-of-paper-in-publishing/

The link below is to an article that looks at how to reduce the environmental toll of paper in publishing.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/environmental-toll-of-paper-in-publishing/

Lucy Montgomery, Curtin University

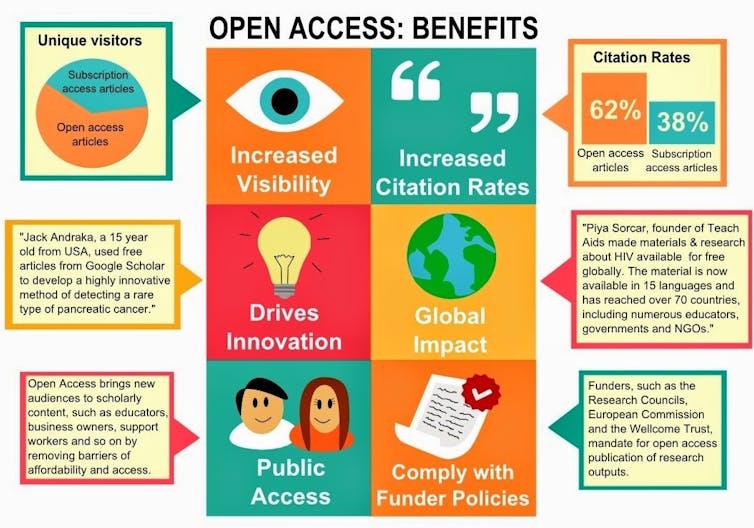

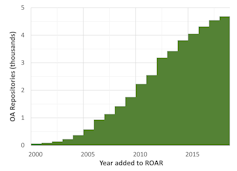

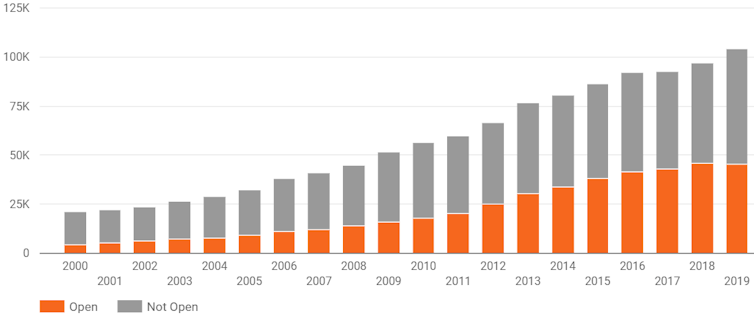

For all its faults, 2020 appears to have locked in momentum for the open access movement. But it is time to ask whether providing free access to published research is enough – and whether equitable access to not just reading but also making knowledge should be the global goal.

In Australia the first challenge is to overcome the apathy about open access issues. The term “open access” has been too easy to ignore. Many consider it a low priority compared to achievements in research, obtaining grant funding, or university rankings glory.

But if you have a child with a rare disease and want access to the latest research on that condition, you get it. If you want to see new solutions to climate change identified and implemented, you get it. If you have ever searched for information and run into a paywall requiring you to pay more than your wallet holds to read a single journal article that you might not even find useful, you will get it. And if you are watching dire international headlines and want to see a rapid solution to the pandemic, you will probably get it.

Many publishing houses temporarily threw open their paywall doors during the year. Suddenly, there was free access to research papers and data for scholars researching pandemic-related issues, and also for students seeking to pursue their studies online across a range of disciplines.

In October 2020, UNESCO made the case for open access to enhance research and information on COIVD-19. It also joined the World Health Organisation and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in calling for open science to be implemented at all stages of the scientific process by all member states.

There is clearly an appetite for freely available information. Since it was established earlier this year, the CORD-19 website has built up a repository of more than 280,000 articles related to COVID-19. These have attracted tens of millions of views.

Europe was already ahead of the curve on open access and 2020 has accelerated the change. Plan S is an initiative for open access launched in Europe in 2018. It requires all projects funded by the European Commission and the European Research Council to be published open access.

Read more:

All publicly funded research could soon be free for you, the taxpayer, to read

A 2018 report commissioned by the European Commission found the cost to Europeans of not having access to FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) research data was €10 billion ($A16.1 billion) a year.

In 2019, open access publications accounted for 63% of publications in the UK, 61% in Sweden and 54% in France, compared to 43% of Australian publications.

Australia’s flagship Australian Research Council has required all research outputs to be open access since 2013. But researchers can choose not to publish open access if legal or contractual obligations require otherwise. This caveat has led to a relatively low rate of open access in Australia.

Read more:

Universities spend millions on accessing results of publicly funded research

The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (AOASG) have long carried the torch for open access in Australia. But, without levers to drive change, they have struggled to change entrenched publishing practices of Australian academics.

Our Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI) project has examined open access across the world. We have analysed open access performance of individuals, individual institutions, groups of universities and nations in recent decades. The COKI Open Access Dashboard offers a glimpse into a subset of this international data, providing insights into national open access performance.

This analysis shows a steady global shift towards open access publications.

For example, in November 2020, Springer Nature announced it would allow authors to publish open access in Nature and associated journals at a price of up to €9,500 (A$15,300) per paper from January 2021. This was a signal change for the publishing industry. One of the world’s most prestigious journals is overturning decades of closed-access tradition to throw open the doors, and committing to increasing its open access publications over time.

At the moment, the pricing of this model enables only a select group to publish open access. The publication cost is equivalent to the value of some Australian research grants. Pricing is expected to become more affordable over time.

Read more:

Increasing open access publications serves publishers’ commercial interests

This international trend is a positive step for fans of freely available facts. However, we should not lose sight of other potentially larger issues at play in relation to open knowledge – that is, a level playing field for access to both published research and participation in research production.

Put another way, we need to pursue not only equity among knowledge takers but also among knowledge makers if we are to enable the world’s best thinkers to collaborate on the planet’s signature challenges.

All of this is good news for people who love to access information – but the bigger overall question for the higher education sector is about the conventions, traditions and trends that determine who gets to be considered for a job in a lab or a library or a lecture theatre. There is much more to be done to make our universities open for all – a future of equity in knowledge making as well as taking.![]()

Lucy Montgomery, Program Lead, Innovation in Knowledge Communication, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Catherine Harris, Sheffield Hallam University and Bernadette Stiell, Sheffield Hallam University

As people seek to educate themselves in response to Black Lives Matter protests, sales of books by black British authors, such as Reni Eddo-Lodge and Bernadine Evaristo, have topped the UK bestseller lists. Several recent prestigious awards have also been won by black writers, including Candice Carty-Williams who won book of the year for Queenie at the British Book Awards. Although proud of her achievement, she was also “sad and confused” on discovering she was the first black author to win this award in its 25-year history.

While these firsts must be celebrated, they also shine a light on publishing’s systemic practices, which have maintained inequalities and under-representation for black, Asian and minority ethnic writers and diverse books. Despite awareness of its shortcomings and years of debates and initiatives (diversity schemes, blind recruiting practices and manuscript submission processes) the industry has generally failed to achieve lasting change. This is because they fail to address the broader systemic inequalities faced by people of colour, which contribute to ongoing under-representation in the industry.

Our research on diversity in children’s publishing included an online survey of 330 responses and 28 in-depth follow-up interviews with people working across the sector. We found that a key barrier has been the engrained perception among industry decision-makers that there is a limited market for diverse books. This is a belief that books written by black and diverse authors or featuring non-white characters just don’t sell.

This perception is seen across the industry, including in children’s literature. This is despite evidence of substantial markets. For instance, a third of English primary pupils are from a black, Asian or minority ethnic background. However, a report by the Centre For Literacy in Primary Education revealed that although the number of black, Asian and minority ethnic protagonists in children’s books had increased from 1% in 2017 to 4% in 2018, there is still a long way to go to achieve representation that reflects the UK population.

Similarly, BookTrust reported that only 6% of children’s authors published in the UK in 2017 were from ethnic minority backgrounds, only a minor improvement from 4% in 2007.

What we found was that the lack of role models in the books read by children and young people of colour meant that they were less likely to aspire to careers in the sector. From those we spoke to, this was compounded by the lack of diversity, particularly in senior roles, in publishing. For those who had pursued a publishing career, experiences of everyday racism and microaggressions were widespread. This added to feelings of frustration and a sense that they were not welcome or did not belong in the industry.

This all has a knock-on effect on what gets published. Authors of colour that we spoke to expressed frustration about the commissioning process. This included quotas for books by or featuring people of colour, a perceived limited appeal for these books and a feeling that authors of colour could only write about race issues.

Reliance on “traditional routes” to publishing also disadvantages black and working-class authors. Publishers reported receiving high volumes of submissions and heavy workloads led to them relying on established writers rather than seeking out new, diverse talent. This has the impact of narrowing the pool of authors from which books are published.

Our participants – including authors, illustrators, editorial assistants and agents – widely reported that a lack of cultural understanding can also lead to the view that diverse books are a riskier investment. They explained how limited promotion and marketing budgets often resulted in lower sales, reinforcing perceptions of limited demand. From their experience, miscommunication at subsequent points along the supply chain about the demand for and availability of diverse books means that those that are published may not even reach bookshop shelves.

These interconnected factors (among others) create a negative cycle which perpetuates the lack of representation of minorities across all parts of the sector, including the lack of authors of colour being nominated for prizes and awards. Recommendations from our research include ensuring diversity on selection panels for events and awards and some good work is already taking place. However, more systematic collaboration and commitment from the sector will be required to produce lasting and meaningful changes and achieve equality and representation.

Our research participants pointed out that social media was allowing individuals to more effectively come together and raise their voices in support of diversity and representation. They expressed hope that this may help to drive forward meaningful and lasting change in the sector. There are signs that this may be the case with recent campaigns emerging in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The #publishingpaidme campaign highlighted racial disparities in publishing advances. The publisher Amistad, an imprint of Harper Collins dedicated to multicultural voices, ran the campaign #BlackoutBestsellerList and #BlackPublishingPower to draw attention to black authors and book professionals and demonstrate the market for these books. The newly formed Black Writers’ Guild, including many of Britain’s best-known authors and poets, wrote an open letter airing concerns and demanding immediate action from publishers. The hope is that these campaigns can focus the industry on bringing about meaningful change.![]()

Catherine Harris, Research Associate, Sheffield Hallam University and Bernadette Stiell, Senior research fellow in the Sheffield Institute of Education, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at women and African publishing.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/how-women-are-changing-the-face-of-african-publishing/

The links below are to articles that take a look at Apple Books for Authors.

For more visit:

– https://davidgaughran.com/2020/05/08/apple-books-for-authors-launches-pc/

– https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-publishing/apple-books-for-authors-platform-makes-publishing-easy

The link below is to an article that looks at the impact of the coronavirus on Chinese publishing.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/coronavirus-has-ground-chinese-publishing-to-a-halt/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at getting started with audiobook publishing.

For more visit:

https://www.janefriedman.com/audiobook-publishing/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at ‘Bookshop,’ an attempt to strike back against Amazon.

For more visit:

https://www.wired.com/story/bookshop-org/

John Kinsella, Curtin University

I start with a disclaimer: I am a UWA Publishing poet. I have published a book of poetry with them (as well as a novel), and have two books forthcoming with them in 2020 — The Weave, a collection of poetry co-written with Thurston Moore, and an edited and introduced volume, The Collected Poems of C.J. Brennan, the great, Sydney-dwelling, symbolist poet (1870-1932).

Now, with UWAP on the verge of being shut down, partly through what I and many others see as a misguided sense of what constitutes an interface between universities and the broader public, the fate of these books is unclear.

The University of Western Australia has proposed that “UWA Publishing operations, in their current form, come to an end” to be replaced by an open-source digital publishing model. The jobs of its employees and director Terri-ann White would likely be “surplus to requirements”. In a statement released late last week it said

Current publishing works already in train this year and next year are expected to continue, as will consultation on innovation that will assist UWA Publishing to adapt to the demands of modern publishing, with options to examine a mix of print, greater digitisation and open access publishing.

But even if contracted books are published, the closure of this publisher would be catastrophic for Australian poetry. It would be as if those books didn’t exist as something connected to a future vision of writing with purpose and community. It’s a way of killing a humanistic, inter-cultural conversation. It ignores the people who do so much to make these conversations happen.

UWAP, especially since 2016, publishes many poetry books a year — a very unusual act of creative support and belief. Its dynamic list includes such essential voices as Ania Walwicz, Candy Royalle, Peter Rose, Quinn Eades, Kate Lilley, David McCooey, and so many other voices of the now, along with collected and selected “greats” like Francis Webb, Lesbia Harford, and Dorothy Hewett.

Yes, I speak here from the inside, as an author. Yet I also speak from the outside as a reader of poetry, and with the incredible feeling of loss I get as a reader, at this ill-thought out proposal.

UWAP publishes many “big name” writers and scholars, but also many marginalised voices and/or voices that might find it hard to publish through purely market-driven publishing houses. It is part of the country’s literary and scholarly collective conscience.

Poetry is an active ingredient of social justice not only in what it can say and talk about, but in the way that it places language under pressure, and questions how expression is used in general discourse, and why. Words of oppression are so easily accepted — poetry questions the uses and “deployment” of language.

UWAP, under Terri-ann White, is part of a clutch of poetry publishers in Australia — and there are not many — who make a commitment to poetry beyond the canonical, and with a strong sense of the need to enact this scrutiny of language. What is said in poetry is seen to matter, and I believe it does.

I will never forget speaking to the late Fay Zwicky in 2017, in her last weeks, about her forthcoming Collected Poems (UWAP, edited by Lucy Dougan and Tim Dolin) and her discussion of proofs and the book itself. A life’s work — one of the great bodies of poetry produced in Australia.

Zwicky had published volumes of poetry with other vital publishers in the Australia poetry community, University of Queensland Press and Giramondo. And then the collation of a life’s work — a big project that required so much attention and goodwill. It was clearly necessary, if not essential, to her.

One of the many titles on the UWAP list that had a remarkable effect on so many readers, and which I noted in the Australian Book Review’s 2018 Books of the Year feature, was a collation of Lisa Bellear’s poetry — Aboriginal Country. As I said then, “the emphatic, committed voice of this remarkable Goernpil woman, feminist, poet, photographer, and activist shines through.” Not to have had access to Bellear’s work is unimaginable now we have encountered it gathered in this way.

There is huge engagement in seeing such a work through to press. It was edited (by Jen Jewel Brown), supported and seen onto the shelves via UWAP. An act of belief and support, among many such acts in a given year; all necessary.

Vitally, UWAP’s poetry list effectively manages that seemingly complex interaction between local work and that from the rest of the country. It seems too often assumed that a WA publisher will necessarily only publish WA work. Now, don’t get me wrong, I am a total believer in local publishing, but there’s also a strong necessity for a publisher that brings many localities together, as Magabala Books in Broome does with Australian Aboriginal writing.

UWAP publishes poets (and writers in general) from all over the country, and brings in some overseas titles as well. Terri-ann White actively takes her lists to readers and publishers outside Australia, and is an energetic and steadfast voice in international publishing for her authors, and for Australian and world literature.

To close UWAP would be a damaging of shared difference, of making community and discussion out of diverse voices.

While I have had the good fortune over the years to publish with some of the major poetry houses around the English-speaking world, I am especially proud and excited when a book of mine is selected for the UWAP list.

Shutting down UWAP would sever many ties and disrupt many conversations just begun, or prevent other conversations, especially of conscience, ever taking place.![]()

John Kinsella, Professor of Literature and Environment, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Emmett Stinson, Deakin University

There has been no shortage of bad news for Australia’s literary and publishing sector in the last year. Major literary journals Island and Overland have been defunded. Only 2.7% of Australia Council funding went to books and writing. The Chair in Australian Literature at University of Sydney is not being renewed.

Two major projects by literary academics were recommended for funding by the Australian Research Council’s peer-review process in 2018, but were rejected by ministerial discretion. Melbourne University Publishing’s CEO, Louise Adler, resigned after the university asked for a change in editorial direction.

And now University of Western Australia has announced dramatic changes to its highly-decorated press, University of Western Australia Publishing. These changes involve not renewing the contract of Director Terri-ann White, deemed “surplus to requirements”, and an end to current publishing activities.

It would be hard to blame writers and literary academics for feeling paranoid. Just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

In 2006, Mark Davis published The Decline of the Literary Paradigm in Australian Publishing.

He argued that between WWII and the 1990s, Australian publishers embraced their role in shaping national culture by subsidising unprofitable literary works with profits from more commercial titles. But by the 2000s, publishers had become neoliberal organisations that sought to maximise profits rather than support literary culture.

We are now seeing this same logic applied by universities.

Universities are increasingly focused on metrics driving enrolments, international rankings and research excellence. This, in turn, supports government funding and research grant income. Universities increasingly prioritise these metrics over cultural contributions that are harder to quantify.

Read more:

Why Australia needs a new model for universities

A statement released by UWA claims the changes will help “to guarantee modern university publishing into the future”, foreshadowing “a mix of print, greater digitisation and open access publishing.”

This statement might appear to mirror recent events at Melbourne University Press last year, but these situations are very different.

Academics had long questioned Melbourne University Press’ publication of works with commercial and political appeal but no clear scholarly or cultural value.

Professor Ronan McDonald summed up this view earlier this year when he wrote that Melbourne University Press was “a trade press irritatingly obliged to publish a few academic titles”.

Melbourne University reaffirmed its commitment to the Press by hiring a respected scholarly publisher, founding director of Monash University Publishing Nathan Hollier, with a track record of producing scholarly titles alongside prize-winning works for a general readership.

UWA Publishing, on the other hand, is one of our leading literary publishers, cultivating authors and significant titles often overlooked by commercial publishers.

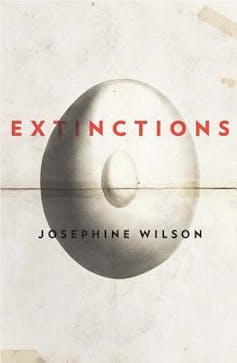

It published Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions, which won the Miles Franklin Award in 2017; is one of Australia’s foremost publishers of poetry; and has published scholarly works by leading Australian humanities academics, such as John Frow, Ross Gibson, and Ken Gelder. It has also published a series of traditional Noongar stories retold by the award-winning author Kim Scott

It has always balanced commitments to scholarly publishing with a significant literary list.

The notion that a respected publishing house can be replaced by open access publishing is disproved by examining other Australian university presses, such as the now-closed University of Adelaide Press, founded in 2009 with a mission to be an open access publisher.

While the press generated many interesting titles, it failed to have a cultural impact. Open access enables free and easy dissemination of work, but this does not meant that it engages with literary culture. Scholars can access works freely, but titles are isolated from bookshops, reviews, and cultural conversations.

Sydney University Press, which was relaunched in 2003 after closing in 1987, has employed a “hybrid approach” to open access. It is now returning to a more standard university publishing model, establishing a research series with dedicated editorial boards of academics, and even publishing a novel, Joshua Lobb’s The Flight of Birds, shortlisted for the Readings New Fiction Prize in 2019.

Open access has an important role to play in academic publishing, but it is laughable to claim UWA Publishing’s cultural impact can simply be replaced through open access.

There is a campaign underway to save UWA Publishing, including a petition with over 6,000 signatures.

It is hard to know at this stage if it will have any effect. It may be the publishing house is the victim of larger financial pressures currently affecting University of Western Australia.

This, of course, is the problem for the literary sector more generally: when cuts are needed, literature is always first on the chopping block.![]()

Emmett Stinson, Lecturer in Writing and Literature, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.