Kathryn MacCallum, University of Canterbury

We know COVID-19 and its associated changes to our work and learning habits caused a marked increase in the use of technology. More surprising, perhaps, is the impact these lockdowns have had on children’s and young people’s self-reported enjoyment of books and the overall positive impact this has made on reading rates.

A recent survey from the UK, for example, showed children were spending 34.5% more time reading than they were before lockdown. Their perceived enjoyment of reading had increased by 8%.

This seems logical — locked down with less to do means more time for other activities. But with the increase in other distractions, especially the digital kind, it’s encouraging to see many young people still gravitate towards reading, given the opportunity.

In general, most children still read physical books, but the survey showed a small increase in their use of audiobooks and digital devices. Audiobooks were particularly popular with boys and contributed to an overall increase in their interest in reading and writing.

There is no doubt, however, that digital texts are becoming more commonplace in schools, and there is a growing body of research exploring their influence. One such study showed no direct relationship between how often teachers used digital reading instruction and activities and their students’ actual engagement or reading confidence.

Read more:

There’s more than one good way to teach kids how to read

What the study did show, however, was a direct, negative relationship between how often teachers had their students use computers or tablets for reading activities and how much the students liked reading.

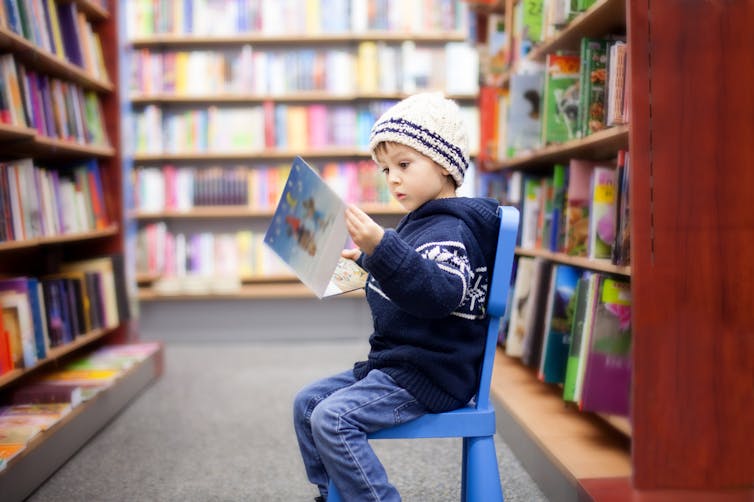

These findings suggest physical books continue to play a critical role in fostering young children’s love of reading and learning. At a time when technology is clearly influencing reading habits and teaching practices, can we really expect the love of reading to be fostered by sitting alone on a digital device?

http://www.shutterstock.com

The limitations of eBooks

In schools and homes we often see eBooks being used to support independent reading. As teachers and parents, we have started to rely on these tools to support our emerging readers. But over-reliance has meant losing the potential for engagement and conversation.

Studies have shown children perform better when reading with an adult, and this is often a richer experience with a print book than with an eBook.

Reading when we’re young is still a communal experience. My own seven-year-old is at the age when reading to me at night is a crucial part of his development as a reader. Relying on him to sit on his own and read from his device will never work.

Read more:

Has the print book trumped digital? Beware of glib conclusions

This is not to deny the usefulness of eBooks. Their adoption in schools has been led by the desire to better support learners. They provide teachers with an extensive library of titles and features designed to entice and motivate.

These embedded features provide new ways of helping children decode language and also offer vital support for children with special needs, such as dyslexia and impaired vision.

The research, however, suggests caution rather than a wholesale adoption of eBooks. Studies have shown the extra features of eBooks, such as pop-ups, animation and sound, can actually distract the learner, detracting from the reading experience and reducing comprehension of the text.

The book as object

Real books may lack these interactive features but their visual and tactile nature plays a strong role in engaging the reader.

Because books exist in the same physical space as their readers — scattered and found objects rather than apps on a screen — they introduce the role of choice, one of the big influences on engagement.

While generally a reluctant reader, my child loves to flick through books and look at the pictures. He might not necessarily read every word, but books such as Dog Man, Captain Underpants and Bad Guys have provided a fantastic opportunity to engage him.

We have even managed to link reading with our children’s favourite online games. Their Minecraft manuals have become valuable resources and are even taken to friends’ houses on play-dates.

Many of our books are not in the best shape, evidence they are lived with and loved. Second hand shops and school fairs provide a cheap option for adding variety, and libraries are also valuable for supplementing the home shelves.

Keeping it real

But cuts to library budgets and collections, such as have been announced recently by Wellington Central Library, threaten to further undermine the role of the physical book in children’s lives.

School libraries, too, are often the first space to be sacrificed when budgets and space restrictions tighten. This encourages the uptake of digital books and further reinforces a reliance on technological alternatives.

Read more:

Do we really own our digital possessions?

Of course, digital technology plays an important role in supporting children to engage and learn, often in powerful new ways that would otherwise be impossible.

But in our haste to adopt and rely on “digital solutions” without clear justification or consideration of their effective use, we risk undervaluing the power of objects made from paper and ink.

As we emerge from a pandemic that has accelerated digital progress, we can’t let these developments obscure the place of real books in real — as opposed to virtual — lives.![]()

Kathryn MacCallum, Associate Professor, University of Canterbury

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.