Man Booker

Adam Kelly, University of York

I am someone who reads, teaches, and writes about contemporary American fiction for a living. Knowing this, you might expect that fresh, experimental novels would constantly be arriving on my desk, that I would be inundated with literary innovation.

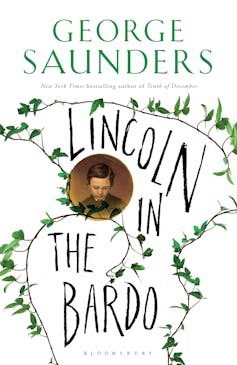

But it is in fact rare to come across a book that does something genuinely new and startling with the form of the novel, a form with a long and distinguished history. George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo, which last night won the 2017 Booker Prize, is that rare kind of book. I had read all of Saunders’s short fiction collections, as well as a great many interviews and essays, before opening his first novel. Yet despite what should have been ideal preparation, I was unprepared for what I found there.

As any student of American history knows, the ostensible subject of Lincoln in the Bardo is the most revered of all US presidents. Abraham Lincoln was an autodidact who rose to fame from an inauspicious backwoods upbringing. He became president at what remains the most fraught moment in American history. He led the north to victory in the Civil War, and abolished slavery by signing the Emancipation Proclamation. He thought like a legal scholar but projected the empathy of a statesman. His speeches are among the greatest ever made by a politician. And he was assassinated as the war drew to a close, ensuring his legacy could not be tarnished by any future descent from the height of his powers.

Lincoln is also one of the most written about men in history, a subject of endless fascination. He has been explored by countless scholars, imagined by myriad writers, embodied by numerous actors on stage and screen. How then to write about Lincoln in a new way, to imagine not only the man himself but all he has come to represent in and for American culture?

Wikimedia Commons

Tackling Lincoln

Lincoln in the Bardo answers this question in two surprising ways. First, Saunders does not focus his primary attention on Lincoln, but on the spirits who inhabit the cemetery in which his 11-year-old son Willie has been buried. Reading the novel’s opening line – “On our wedding day I was forty-six, she was eighteen” – we initially assume that we are hearing the voice of Abraham Lincoln, perhaps coming to us from the mysterious space of the bardo, the realm in Buddhist mythology that lies between death and rebirth.

It soon becomes clear, however, that the facts do not fit with this reading, and nor does the tone. On the third page, we discover that the speaker is one “hans vollman”, in conversation with someone called “roger bevins iii”. These are not famous men, nor are they taken up with famous acts. They are discussing the fatal accident experienced by vollmann when he was hit by a beam while in the first flush of sexual arousal with his virgin bride. Echoing the setting and tone of Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s Irish-language classic Cré na Cille, Lincoln in the Bardo begins like a bawdy black comedy.

In building a fictional world from this unexpected opening, the second key decision Saunders makes is to refuse to do what writers of historical fiction have always done, which is to conceal the sources of their research and imagine their subject fresh onto the page. Instead, Saunders quotes a wide range of scholarly passages verbatim, attributing the quotations to their author and text.

Bloomsbury

These passages are drawn from what historians call primary sources (letters and memoirs from Lincoln’s contemporaries) and secondary sources (scholarly accounts of Lincoln in the 150+ years since his death). Most of these sources are real, some are invented, and it’s not always clear which is which. The result is a novel that powerfully transmits the cumulative and collective effort to write history, to do justice to the past and what it means.

A democracy of contradictions

The mix of these two registers – the comic and the scholarly – shouldn’t work, but it does. Once the reader has settled into the rhythm of alternating chapters dealing with the chaotic world of the spirits and the more sober (but sometimes equally peculiar) scholarship on Lincoln, Saunders’s project gains clarity, purpose and power. Populated with a multitude of voices, the novel addresses the great faultlines of American democracy – race, gender, wealth, sexuality – while keeping its eye firmly on the common ground its characters share in their inevitable confrontation with life and death.

In a creative writing masterclass with Saunders that I attended earlier this year at the University of Liverpool, the author outlined his vision of literary stories as “active systems of contradiction”. In mixing together what we usually think of as opposites – tragedy and comedy, high rhetoric and bawdy farce, private grief and political action, the individual and the collective – stories can challenge our sense that some things must be kept apart. We come to see that these apparent opposites are in fact different faces of a fundamental unity. This is the unity that underpins our connection to one another in a shared world.

In writing Lincoln in the Bardo, Saunders couldn’t have known how directly his themes would speak to an America and a world in which contradictions are becoming increasingly stark and oppositions are being set in stone. The Booker Prize jury has done us a favour by drawing attention to a book that tries to forge a unity among opposites in the most surprising ways.

![]() Despite its origins in grief and mourning, Saunders’s message is a refreshingly hopeful one. We can only hope the message is heard by those whose ears it needs to reach.

Despite its origins in grief and mourning, Saunders’s message is a refreshingly hopeful one. We can only hope the message is heard by those whose ears it needs to reach.

Adam Kelly, Lecturer in American Literature, University of York

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.