Jodi McAlister, Deakin University

She published more than 70 novels and sold more than 34 million books translated into 29 languages, making her one of Australia’s most successful and prolific authors. Yet many are not familiar with her name.

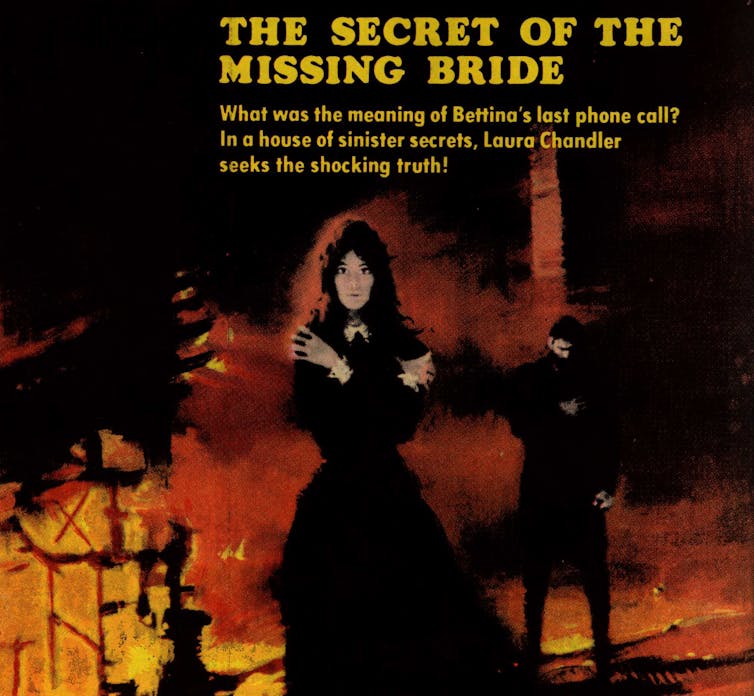

Valerie Parv passed away suddenly last weekend, a week before her 70th birthday. She began as an advertising copywriter, and her first books, non-fiction home and garden DIY guides, were published in the late 1970s. In the 1980s, she began to publish in the genre she was most well-known for: romance fiction.

Her first romance novel, Love’s Greatest Gamble, was published by Harlequin Mills & Boon in 1982. This was, as Parv noted, a book which “broke a few moulds at the time”, featuring a widowed single mother heroine dealing with the fallout of her late husband’s PTSD-induced gambling addiction.

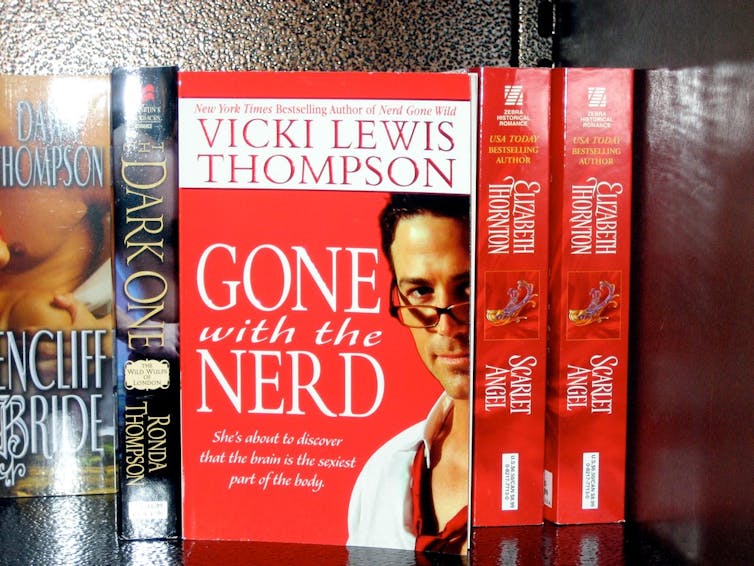

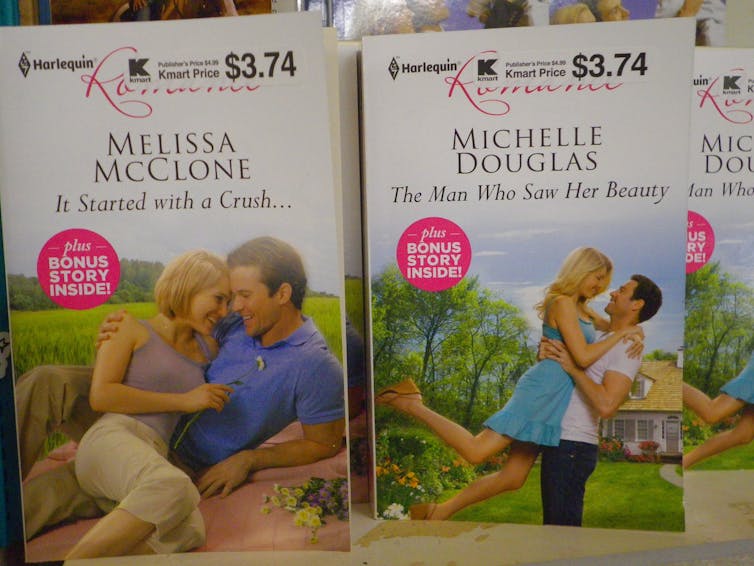

Parv went on to write 56 more romances across various Harlequin imprints. With these books, she was primarily working in the genre known as category romance — most frequently associated with Mills & Boon in Australia, and sold in print at discount department stores like Kmart, Big W and Target.

Romance fiction is often derided as formulaic. This is especially true for category romance fiction, as publisher guidelines can dictate things like length, setting and level of sexual content. Parv, however, firmly rejected this notion.

“All fiction has conventions but formula, hardly,” she wrote earlier this month.

“Not when people and their stories are so varied.”

Romance, and aliens

In addition to writing romance, Parv also wrote science fiction novels and a number of non-fiction works. She is the only Australian recipient of the Romantic Times Book Reviews Pioneer award, which honours those who have broken new ground in the development of the romance novel.

Parv was unafraid to experiment, enjoining aspiring authors to “write dangerously” rather than to satisfy the market, and often hybridised genres in her work.

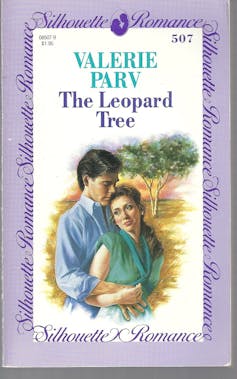

She frequently told an anecdote about her 1987 book The Leopard Tree, which raised the possibility its hero might have arrived by UFO.

While she received pushback on this from the English Harlequin imprint Mills & Boon, the book was published by the American imprint Silhouette, where the book, she would say, “became the poster-child for cutting edge romance for some years afterward”.

Completing her masters degree in 2007, Parv’s thesis was inspired by a question often posed to her by aspiring authors: “where do you get your ideas?”

Read more:

What’s next after Bridgerton? 5 romance series ripe for TV adaptation

She explored this question in relation to both her own work and the work of other authors, concluding authors often revisit themes and ideas resonant with their own lives, whether consciously or unconsciously.

In her own work, she observed a consistent preoccupation with characters resolving feelings of alienation, which she linked to the fact her family emigrated from Britain when she was seven, leaving her with a sense of rootlessness.

A writers’ writer

Parv’s professional career is as much a story of community-building as it is the story of an individual author.

An enormous part of her legacy will be her bestselling guides on the craft of writing, including The Art of Romance Writing (1993), Heart and Craft (2009), and, most recently, her part memoir/part writing advice volume 34 Million Books (2020), the title of which is a wink to her own prolific success.

In her writing guides, Parv focused unerringly on practical advice for writing, but also steered away from prescriptivism.

“There’s no one way to write a romance novel, no ‘secret’ that can be applied to every writer and every story,” she wrote in the introduction to Heart and Craft.

Parv was also strongly committed to mentorship. For 20 years, the Valerie Parv Award was run through the Romance Writers of Australia. Winners of the award — fondly referred to by Parv as her “minions” — received a year’s mentorship with Parv.

Nearly all of Parv’s minions have gone on to have works published. Their numbers include several highly successful romance authors, such as Kelly Hunter, Rachel Bailey and Bronwyn Parry.

In 2015, Parv was made a Member of the Order of Australia for significant contributions to the arts — both as a prolific author and as a mentor.

‘I believe in romance’

As a genre, romance fiction has never enjoyed an enormous amount of respect from outside its readership. For this reason, Parv — like her highly prolific and successful peer Emma Darcy, who predeceased her by four months — may never be a household name, despite her service to Australian literary culture: a fact of which she was well aware.

Despite this, she never ceased to advocate for the genre in which she made her career, and in which she assisted so many others to do the same.

“I will never send up romance in any form, because I believe in romance,” she commented on the Secrets From The Green Room podcast one month before her death.

“I’ve been in love, and I know how important it is to my life, and how it is to most people’s lives.”

Read more:

How to learn about love from Mills & Boon novels

![]()

Jodi McAlister, Lecturer in Writing, Literature and Culture, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.