The link below is to an article that takes a look at Graphite Comics, an unlimited comics platform.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-comic-news/graphite-comics-is-a-new-unlimited-comics-platform

The link below is to an article that takes a look at Graphite Comics, an unlimited comics platform.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-comic-news/graphite-comics-is-a-new-unlimited-comics-platform

The link below is to an article that takes a look at Comic Rack and how to organise your comics by using it.

For more visit:

https://www.makeuseof.com/tag/how-to-organize-comic-collection/

The link below is to an article that looks at comic book podcasts.

For more visit:

https://www.iheart.com/content/2019-04-09-best-podcasts-for-comic-book-geeks/

The link below is to an archive website called the Digital Comic Museum.

For more visit:

https://digitalcomicmuseum.com/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at where to find free books and comics.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/02/11/free-books-and-comics/

Camilla Nelson, University of Notre Dame Australia

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

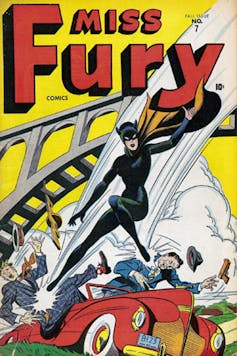

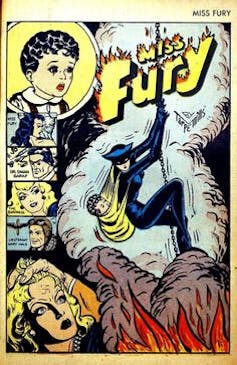

In April 1941, just a few short years after Superman came swooping out of the Manhattan skies, Miss Fury – originally known as Black Fury – became the first major female superhero to go to print. She beat Charles Moulton Marsden’s Wonder Woman to the page by more than six months. More significantly, Miss Fury was the first female superhero to be written and drawn by a woman, Tarpé Mills.

Miss Fury’s creator – whose real name was June – shared much of the gritty ingenuity of her superheroine. Like other female artists of the Golden Age, Mills was obliged to make her name in comics by disguising her gender. As she later told the New York Post, “It would have been a major let-down to the kids if they found out that the author of such virile and awesome characters was a gal.”

Yet, this trailblazing illustrator, squeezed out of the comic world amid a post-WW2 backlash against unconventional images of femininity and a 1950s climate of heightened censorship, has been largely excluded from the pantheon of comic greats – until now.

Comics then and now tend to feature weak-kneed female characters who seem to exist for the sole purpose of being saved by a male hero – or, worse still, are “fridged”, a contemporary comic book colloquialism that refers to the gruesome slaying of an undeveloped female character to deepen the hero’s motivation and propel him on his journey.

But Mills believed there was room in comics for a different kind of female character, one who was able, level-headed and capable, mingling tough-minded complexity with Mills’ own taste for risqué behaviour and haute couture gowns.

Where Wonder Woman’s powers are “marvellous” – that is, not real or attainable – Miss Fury and her alter ego Marla Drake use their collective brains, resourcefulness and the odd stiletto heel in the face to bring the villains to justice.

And for a time they were wildly successful.

Miss Fury ran a full decade from April 1941 to December 1951, was syndicated in 100 different newspapers at the height of her wartime fame, and sold a million copies an issue in reprints released by Timely (now Marvel) comics.

Pilots flew bomber planes with Miss Fury painted on the fuselage. Young girls played with paper doll cut outs featuring her extensive high fashion wardrobe.

Miss Fury’s “origin story” offers its own coolly ironic commentary on the masculine conventions of the comic genre.

One night a girl called Marla Drake finds out that her friend Carol is wearing an identical gown to a masquerade party. So, at the behest of her maid Francine, she dons a skin tight black cat suit that – in an imperial twist, typical of the period – was once worn as a ceremonial robe by a witch doctor in Africa.

On the way to the ball, Marla takes on a gun-toting killer, using her cat claws, stiletto heels, and – hilariously – a puff of powder blown from her makeup compact to disarm the villain. She leaves him trussed up with a hapless and unconscious police detective by the side of the road.

Miss Fury could fly a fighter plane when she had to, jumping out in a parachute dressed in a red satin ball gown and matching shoes. She was also a crack shot.

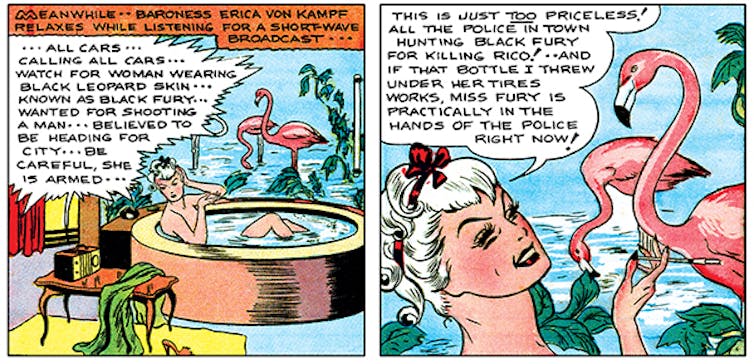

This was an anarchic, gender flipped, comic book universe in which the protagonist and principle antagonists were women, and in which the supposed tools of patriarchy – high heels, makeup and mermaid bottom ball gowns – were turned against the system. Arch nemesis Erica Von Kampf – a sultry vamp who hides a swastika-branded forehead behind a v-shaped blond fringe – also displayed amazing enterprise in her criminal antics.

Invariably the male characters required saving from the crime gangs, the Nazis or merely from themselves. Among the most ingenious panels in the strip were the ones devoted to hapless lovelorn men, endowed with the kind of “thought bubbles” commonly found hovering above the heads of angsty heroines in romance comics.

By contrast, the female characters possessed a gritty ingenuity inspired by Noir as much as by the changed reality of women’s wartime lives. Half way through the series, Marla got a job, and – astonishingly, for a Sunday comic supplement – became a single mother, adopting the son of her arch nemesis, wrestling with snarling dogs and chains to save the toddler from a deadly experiment.

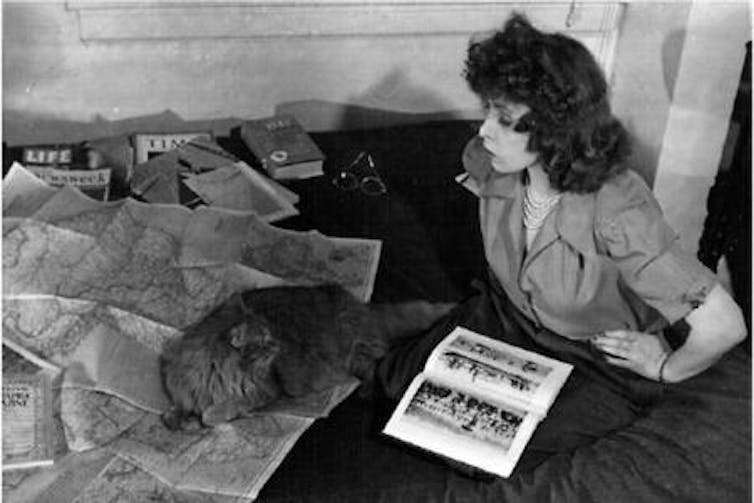

Mills claims to have modelled Miss Fury on herself. She even named Marla’s cat Peri-Purr after her own beloved Persian pet. Born in Brooklyn in 1918, Mills grew up in a house headed by a single widowed mother, who supported the family by working in a beauty parlour. Mills worked her way through New York’s Pratt Institute by working as a model and fashion illustrator.

In the end, ironically, it was Miss Fury’s high fashion wardrobe that became a major source of controversy.

In 1947, no less than 37 newspapers declined to run a panel that featured one of Mills’ tough-minded heroines, Era – a South American Nazi-Fighter who became a post-war nightclub entertainer – dressed as Eve, replete with snake and apple, in a spangled, two-piece costume.

This was not the only time the comic strip was censored. Earlier in the decade, Timely comics had refused to run a picture of the villainess Erica resplendent in her bath – surrounded by pink flamingo wallpaper.

But so many frilly negligées, cat fights, and shower scenes had escaped the censor’s eye. It’s not a leap to speculate that behind the ban lay the post-war backlash against powerful and unconventional women.

In wartime, nations had relied on women to fill the production jobs that men had left behind. Just as “Rosie the Riveter” encouraged women to get to work with the slogan “We Can Do It!”, so too the comparative absence of men opened up room for less conventional images of women in the comics.

Once the war was over, women lost their jobs to returning servicemen. Comic creators were no longer encouraged to show women as independent or decisive. Politicians and psychologists attributed juvenile delinquency to the rise of unconventional comic book heroines and by 1954 the Comics Code Authority was policing the representation of women in comics, in line with increasingly conservative ideologies. In the 1950s, female action comics gave way to romance ones, featuring heroines who once again placed men at the centre of their existence.

Miss Fury was dropped from circulation in December 1951, and despite a handful of attempted comebacks, Mills and her anarchic creation slipped from public view.

Mills continued to work as a commercial illustrator on the fringes of a booming advertising industry. In 1971, she turned a hand to romance comics, penning a seven-page story that was published by Marvel, but it wasn’t her forte. In 1979, she began work on a graphic novel Albino Jo, which remains unfinished.

Despite her chronic asthma, Mills – like the reckless Noir heroine she so resembled – chain-smoked to the bitter end. She died of emphysema on December 12, 1988, and is buried in New Jersey under the simple inscription, “Creator of Miss Fury”.

This year Mills’ work will be belatedly recognised. As a recipient of the 2019 Eisner Award, she will finally take her place in the Comics Hall of Fame, alongside the male creators of the Golden Age who have too long dominated the history of the genre. Hopefully this will bring her comic creation the kind of notoriety, readership and big screen adventures she thoroughly deserves.![]()

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gabriel Clark, University of Technology Sydney

With news that the Man Booker Prize long list includes a graphic novel for the first time, the spotlight is on comics as a literary form. That’s a welcome development; the comic is one of the oldest kinds of storytelling we have and a powerful artform.

Right now, the Australian comics community is producing some of the best original work in the world. Australian comics punch above their weight globally. Many have been picked up by international publishers and nominated for international and national literary awards – yet remain little known at home. Some are directed at an adult audience; some are for all ages. They tackle issues ranging from true crime to environmental ruin to life in detention.

As someone who has researched comics for years – and been a fan since childhood – I want to share with you some highlights from the contemporary Australian comic scene. Here are 10 Australian comics of note, in no particular order.

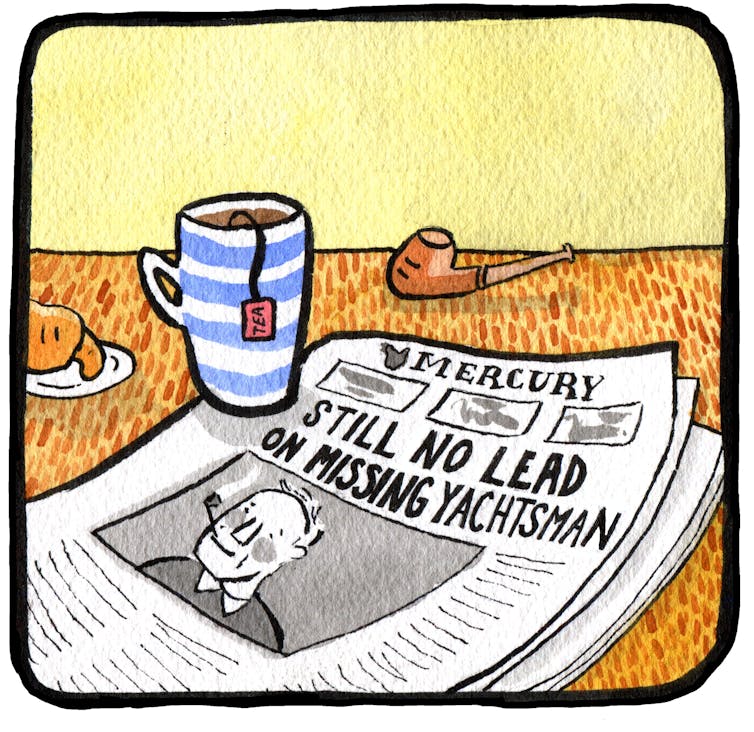

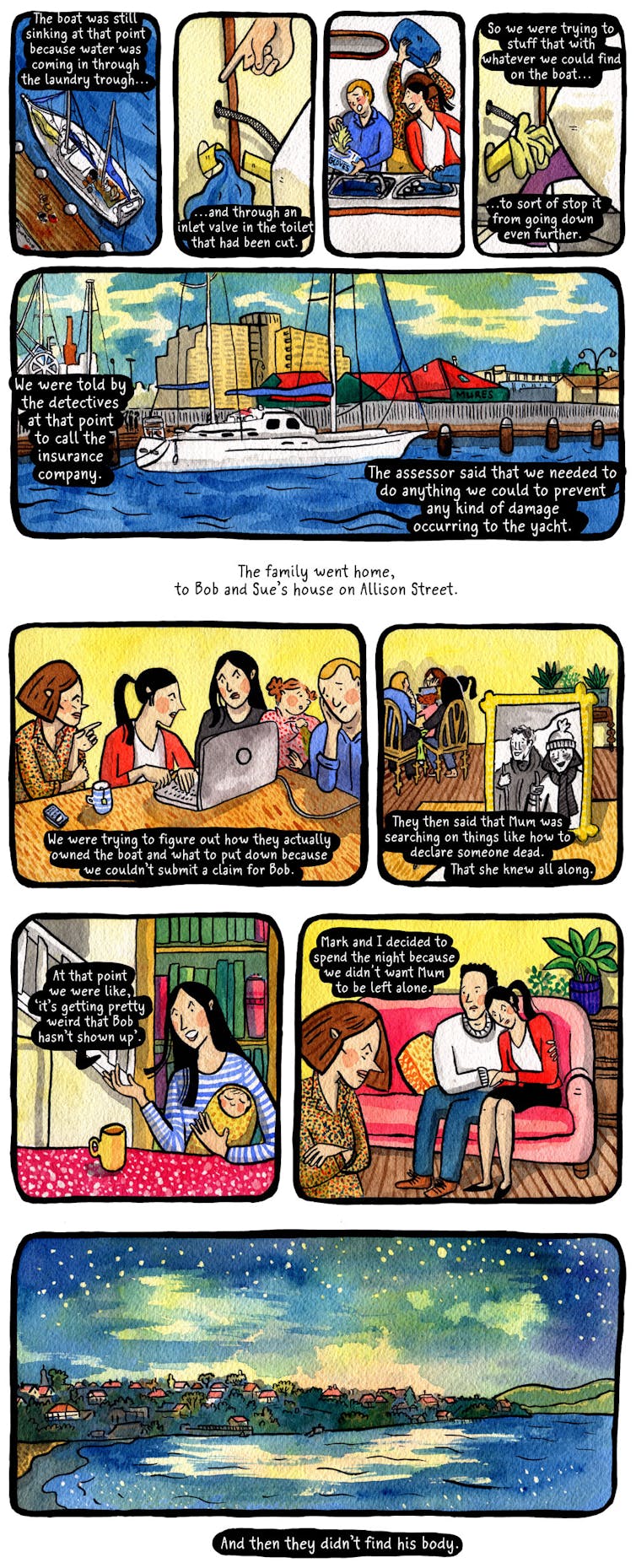

Sue Neill-Fraser’s conviction for the murder of her de-facto partner Bob Chappell in 2009 polarised the Tasmanian city of Hobart. To this day, Sue has maintained her innocence. This piece of long-form comics journalism by cartoonist Eleri Mai Harris takes readers deep into the personal impact this case has had on the families of those involved.

You can read Reported Missing online here.

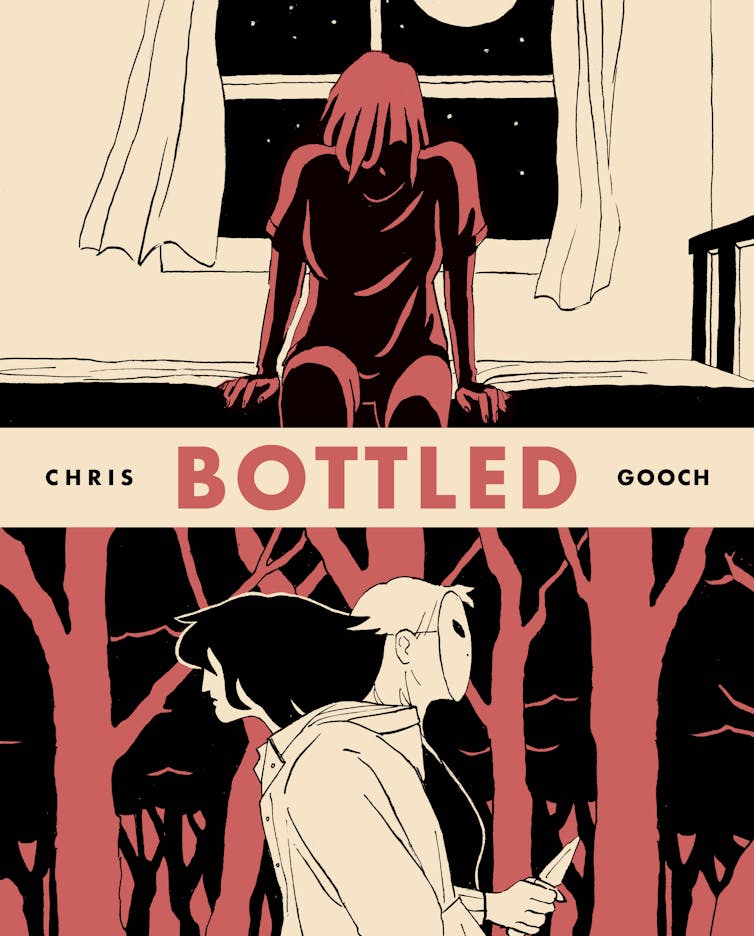

According to one study, mean friends can be good for you. The opposite may be true in this psychological drama, a tale of jealousy, friendship and narcissism. Bottled is a tense piece of suburban noir set in the suburbs of Melbourne, rendered stark and disjointed by Chris Gooch’s striking artwork.

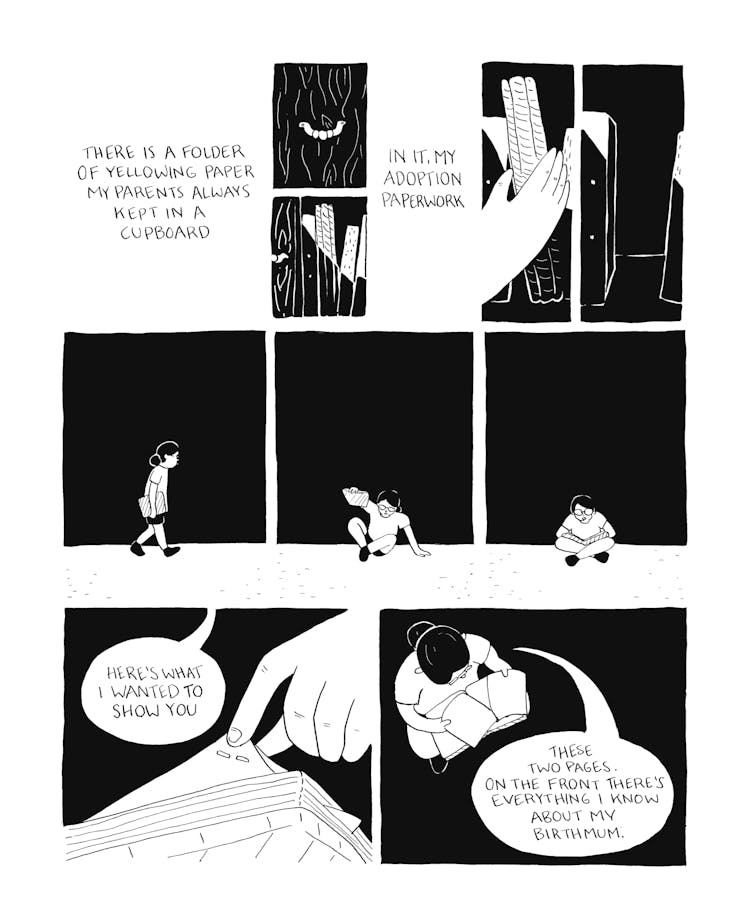

Who is my birth mother? In this autobiographical story, Meg O’Shea travels to Seoul to find an answer to that question, armed with her sense of humour and imagination. This whimsical story of sliding door moments explores the emotional impact of not having solutions and the fatality of not knowing.

You can read A Part Of Me Is Still Unknown here.

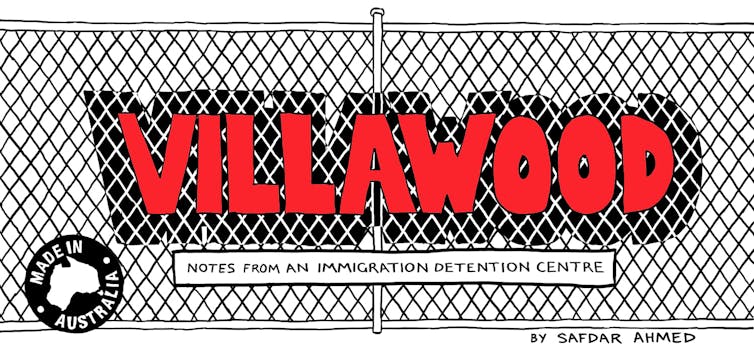

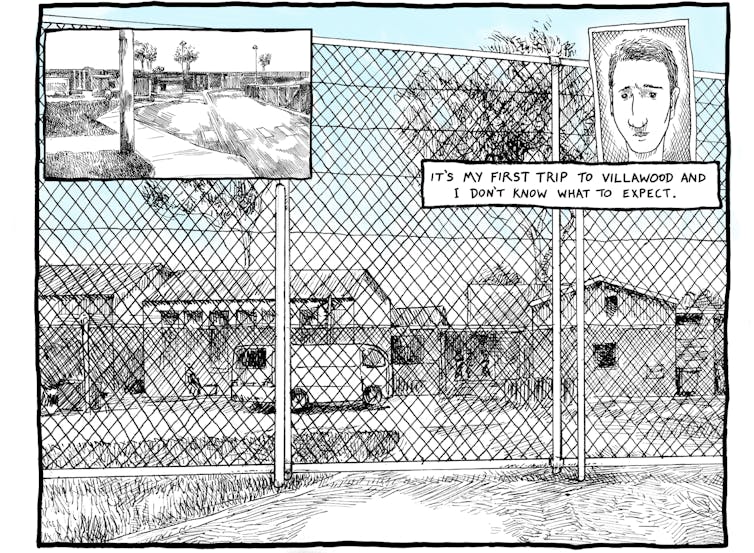

Villawood is a Walkley award-winning piece of comics journalism about the experiences of being held captive in a Sydney asylum seeker detention centre. In sharing the stories and experiences of the detainees, it lays bare the harsh realities of indefinite detention. These stories are made even more real through the inclusion of artwork created by the detainees. Their images sit alongside Safdar’s tense line work, which illustrates the realities of this brutal system.

You can read Villawood online here.

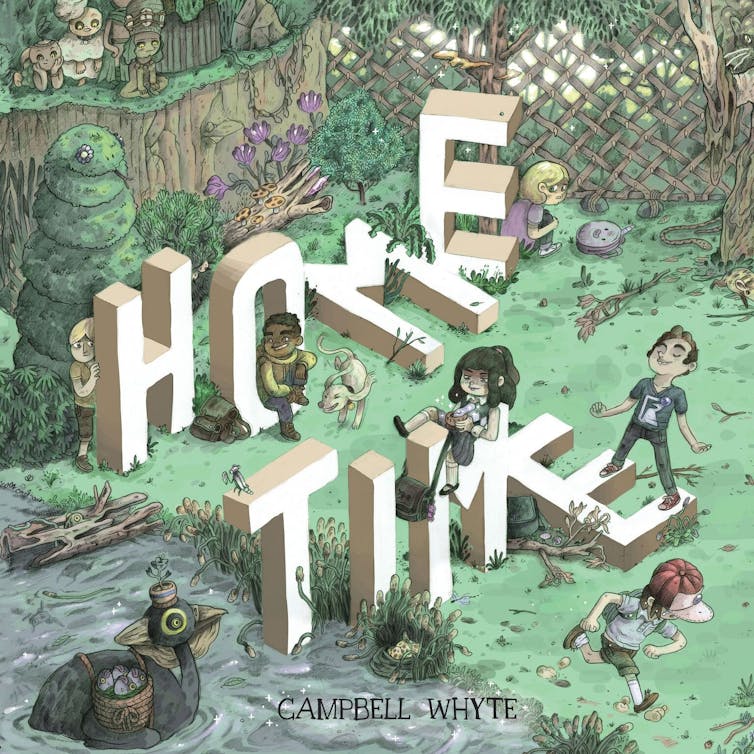

Changes are on the horizon for a group of Year Six school friends who are looking at their last summer together. But their suburban world is transformed after a freak accident transports them to an alternative universe. The friends find themselves in an inverse world filled with creepy gumnut babies, cups of tea and a deceptively familiar Australian landscape. With Home Time, Campbell Whyte has created an intoxicating and visually stunning Australian Narnia.

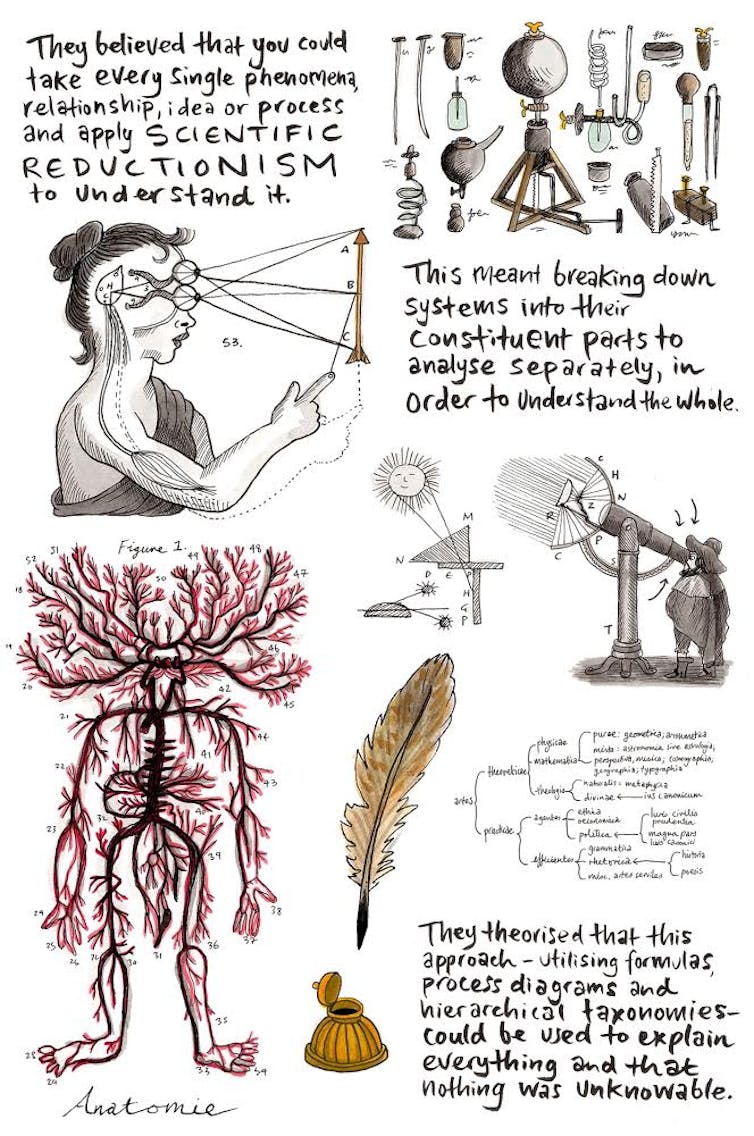

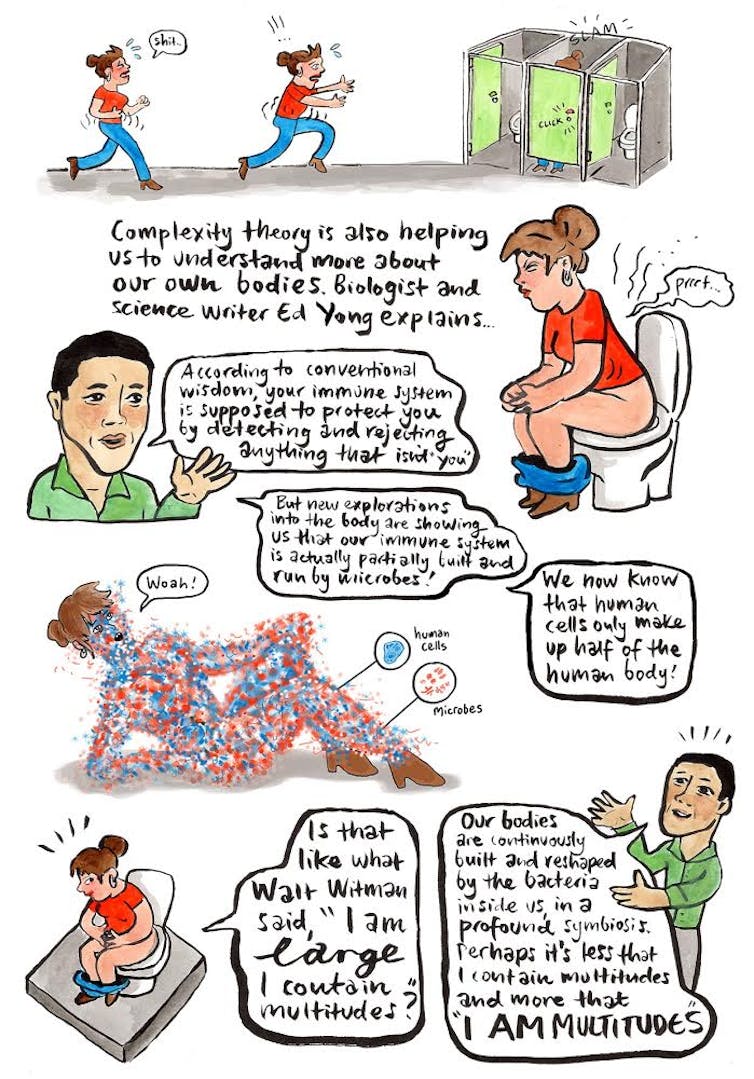

Sarah Catherine Firth’s visual essay explores how we understand the complex systems that exist in the world around us. Through autobiographical anecdotes and humour, it covers the history of scientific thought, unpacks complex ideas and helps provide answers to complicated questions.

You can read Making Sense of Complexity online here.

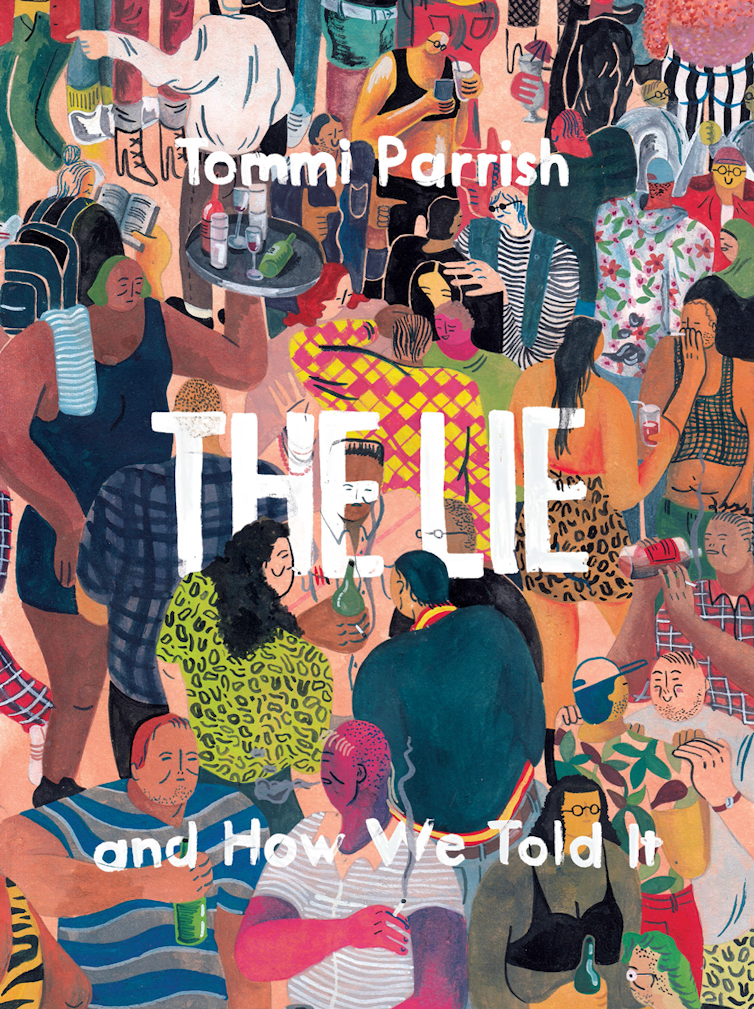

The blurb says The Lie is about how “after a chance encounter, two formerly close friends try to salvage whatever is left of their decaying relationship”. But it’s much more that. Visually, Tommi Parissh’s disproportioned characters dominate the spaces and the panels they inhabit, their uneven bodies reflecting their unease with themselves and their shared history. The Lie is a beautifully poignant tale of confused identities, self-centeredness and regret.

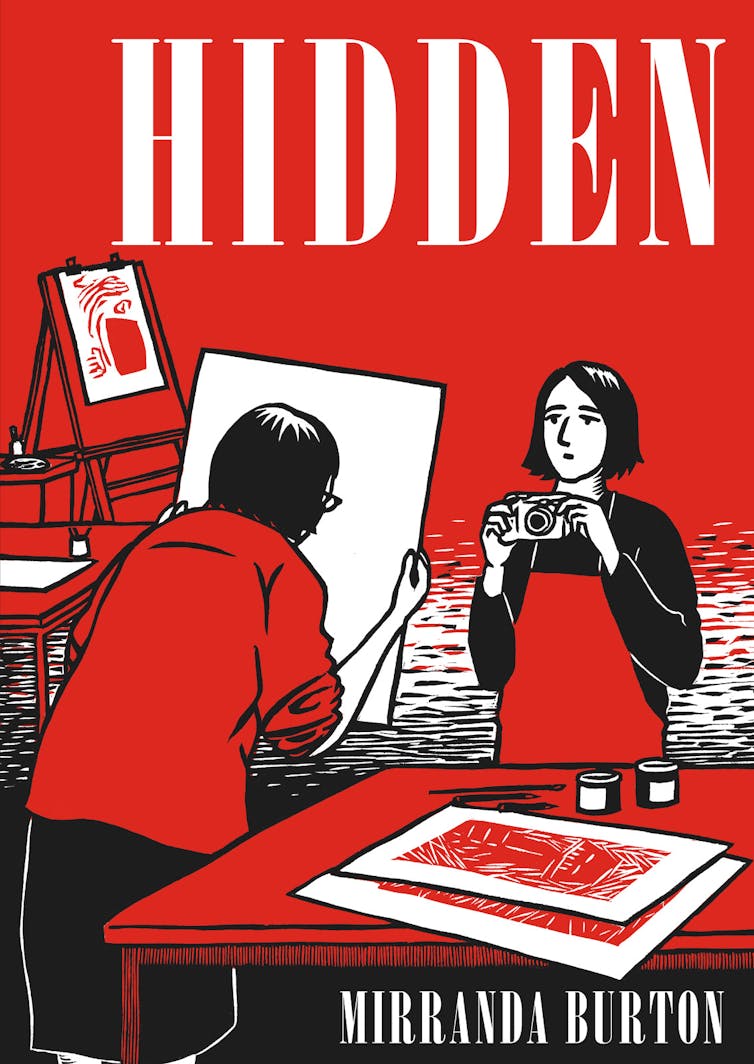

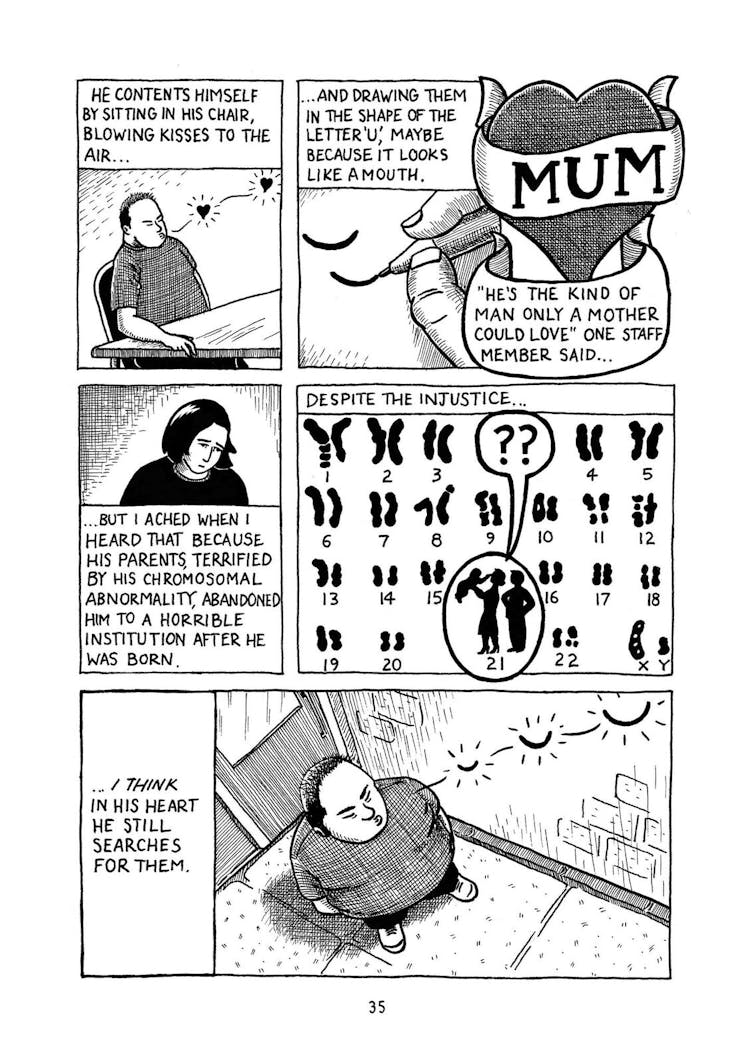

“Everyone sees the world in their own unique way.” That’s how Mirranda Burton introduces Steve, one of the intellectually impaired adults she teaches art to. But Hidden isn’t about how her subjects see the world. It’s about how Mirranda sees them – with care, respect and humour. Mirranda’s fictionalised stories reveal how engaging meaningfully with people can shift your perspectives in beautiful and unexpected ways.

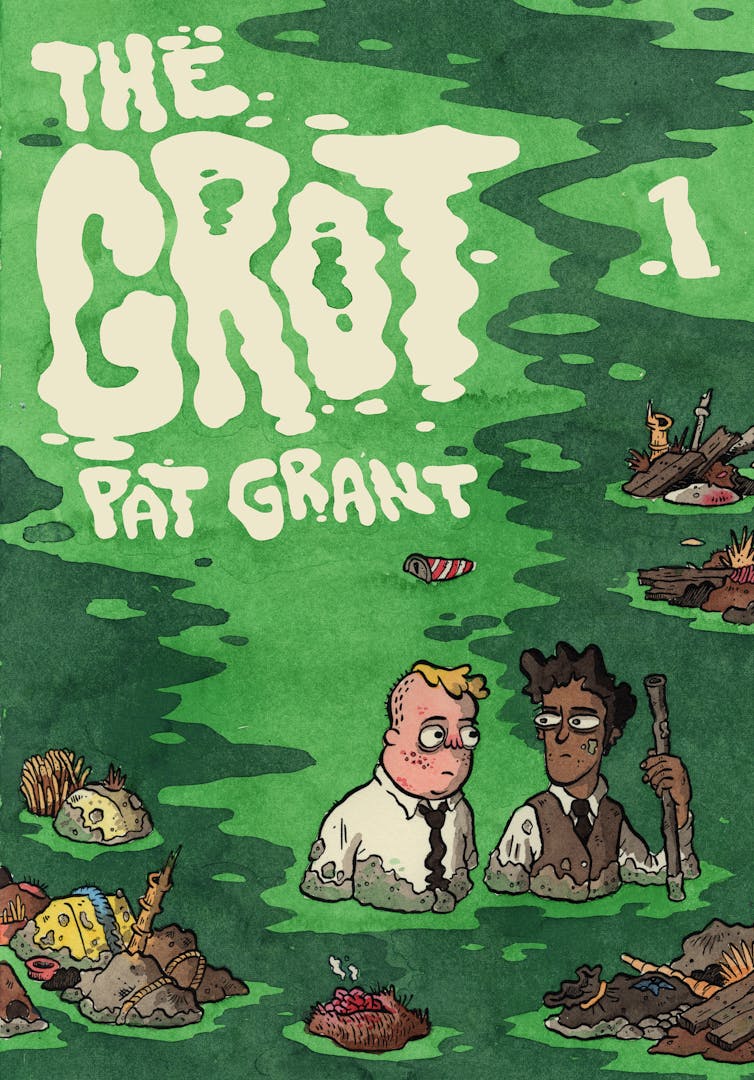

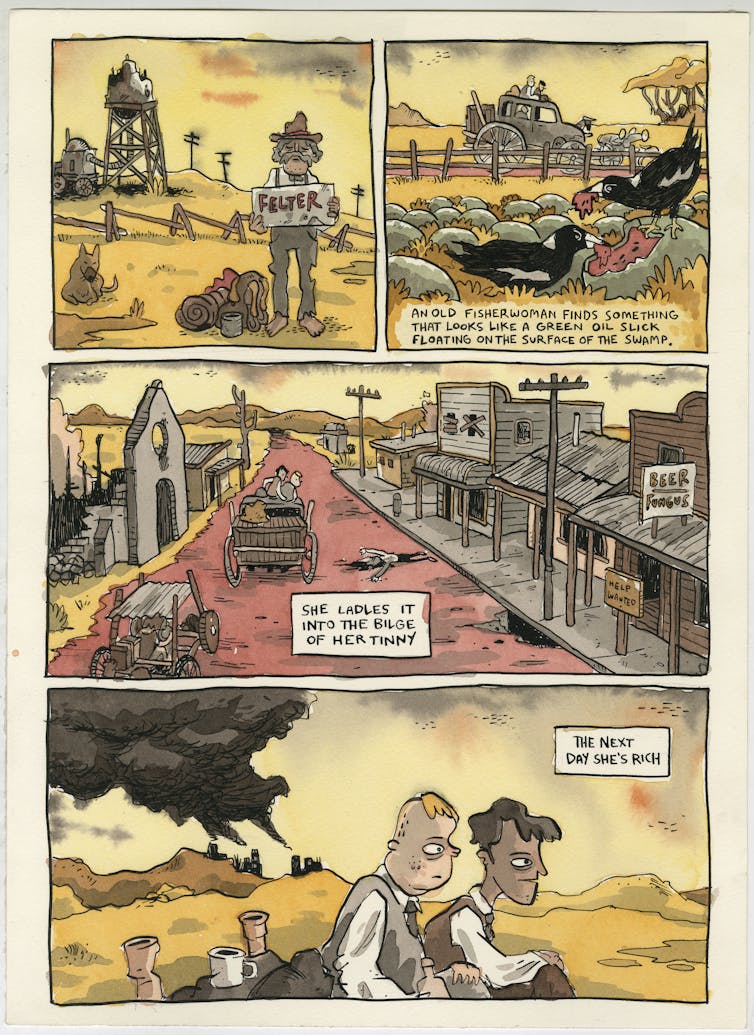

If everyone you know is trying to get rich at everyone else’s expense, then who can you trust? In The Grot, the world is in the wake of an unnamed environmental catastrophe, technology and society have been reduced to simple mechanics, and everyone is rushing to Felter City to make their fortunes. With The Grot, Pat Grant and Fionn McCabe have created a stained and wondrously dilapidated alternative universe of Australian hustlers and grifters fighting to survive in a new Australian gold rush.

You can read The Grot online here.

Sam Wallman’s comic essay So Below explores ideas of land ownership and its social and political ramifications. Sam’s poetic artwork guides the reader through complicated questions to reveal the communities impacted by the social construct of land ownership.

You can read So Below online here.![]()

Gabriel Clark, Lecturer, Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Louise Pryke, Macquarie University

Ancient Mesopotamia, the region roughly encompassing modern-day Iraq, Kuwait and parts of Syria, Iran and Turkey, gave us what we could consider some of the earliest known literary “superheroes”.

One was the hero Lugalbanda, whose kindness to animals resulted in the gift of super speed, perhaps making him the literary great-grandparent of the comic hero The Flash.

But unlike the classical heroes (Theseus, Herakles, and Egyptian deities such as Horus), which have continued to be important cultural symbols in modern pop culture, Mesopotamian deities have largely fallen into obscurity.

An exception to this is the representation of Mesopotamian culture in science fiction, fantasy, and especially comics. Marvel and DC comics have added Mesopotamian deities, such as Inanna, goddess of love, Netherworld deities Nergal and Ereshkigal, and Gilgamesh, the heroic king of the city of Uruk.

The Marvel comic book hero of Gilgamesh was created by Jack Kirby, although the character has been employed by numerous authors, notably Roy Thomas. Gilgamesh the superhero is a member of the Avengers, Marvel comics’ fictional team of superheroes now the subject of a major movie franchise, including Captain America, Thor, and the Hulk. His character has a close connection with Captain America, who assists Gilgamesh in numerous battles.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: the Epic of Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh and Captain America are both characters who stand apart from their own time and culture. For Captain America, this is the United States during the 1940s, and for Gilgamesh, ancient Mesopotamia. A core aspect of their personal narratives is their struggle to navigate the modern world while still engaging with traditions from the past.

Gilgamesh’s first appearance as an Avenger was in 1989 in the comic series Avengers 1, issue #300, Inferno Squared. In the comic, Gilgamesh is known, rather aptly, as the “Forgotten One”. The “forgetting” of Gilgamesh the hero is also referenced in his first appearance in Marvel comics in 1976, where the character Sprite remarks that the hero “lives like an ancient myth, no longer remembered”.

In Avengers #304, …Yearning to Breathe Free!, Gilgamesh travels to Ellis Island with Captain America and Thor. The setting of Ellis Island allows for the heroes’ thoughtful consideration of their shared past as immigrants. Like Gilgamesh, Thor is also from foreign lands, in this case the Norse kingdom of Asgard.

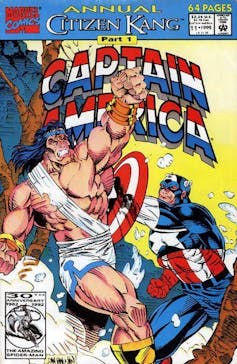

In the 1992 comic Captain America Annual #11, the battle against the villainous Kang sends Captain America time-travelling back to Uruk in 2700 BCE. Captain America realises that the his royal companion is Gilgamesh, and accompanies the king on adventures from the legendary Epic of Gilgamesh.

In the original legend, Gilgamesh finds the key to eternal youth, a heartbeat plant, and then promptly loses it to a snake. In the comic adaptation, the snake is an angry sea serpent, who Captain America must fight to save Gilgamesh. The Mesopotamian hero’s famous fixation on acquiring immortality is reflected in his Marvel counterpart’s choice to leave Captain America fighting the serpent in order to collect the heartbeat plant. This leads Cap to observe his ancient friend has “a few millennia” of catching up to do on the concept of team-work!

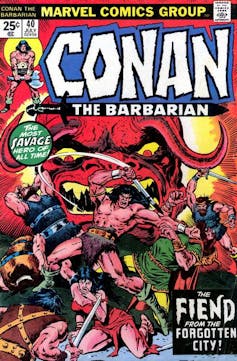

Gilgamesh is not the only hero to feature. Marvel’s 1974 comic, Conan the Barbarian #40, The Fiend from the Forgotten City, features the Mesopotamian goddess of love, Inanna. In the comic, the barbarian hero is assisted by the goddess while fighting against looters in an ancient “forgotten city.” Marvel’s Inanna holds similar powers to her mythical counterpart, including the ability to heal. It is interesting to note the prominence of the theme of “forgetting” in comic books involving Mesopotamian myths, perhaps alluding to the present day obscurity of ancient Mesopotamian culture.

Read more:

Friday essay: the legend of Ishtar, first goddess of love and war

It’s tempting to think that Captain America’s 1992 journey back to Ancient Mesopotamia was a comment on the political context at the time, particularly the Gulf War. But Roy Thomas, creator of this comic, told me via email his portrayal of Gilgamesh reflected his interest in the legend from his university days, and teaching students ancient myths at a high school.

Thomas’ belief in the benefits of learning myths is well founded. Story-telling has been recognised since ancient times as a powerful tool for imparting wisdom. Myths teach empathy and the ability to consider problems from different perspectives.

The combination of social and analytical skills developed through engaging with mythology can provide the foundation for a life-long love of learning. A recent study has shown that packaging stories in comics makes them more memorable, a finding with particular significance for preserving Mesopotamia’s cultural heritage.

The myth literacy of science fiction and fantasy audiences allows for the representation in these works of more obscure ancient figures. Marvel comics see virtually the entire pantheons of Greece, Rome, and Asgard represented. But beyond these more familiar ancient worlds, Marvel has also featured deities of the Mayan, Hawaiian, Celtic religions, and Australian Aboriginal divinities, and many others.

<!– Below is The Conversation's page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. –>

![]()

The use of Mesopotamian myth in comic books shows the continued capacity of ancient legends to find new audiences and modern relevance. In the comic multiverse, an appreciation of storytelling bridges a cultural gap of 4,000 years, making old stories new again, and hopefully preserving them for the future.

Louise Pryke, Lecturer, Languages and Literature of Ancient Israel, Macquarie University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the 2018 Will Eisner Comic Book Awards.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/23/2018-eisner-awards-winners/

You must be logged in to post a comment.