(Shutterstock)

Nada Elnahla, Carleton University and Ruth McKay, Carleton University

Reading fiction has always been, for many, a source of pleasure and a means to be transported to other worlds. But that’s not all. Businesses can use novels to consider possible future scenarios, study sensitive workplace issues, develop future plans and avoid unplanned problematic events — all without requiring a substantial budget.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many business leaders have learned how important it is for businesses to consider a wide range of possible outcomes and to enhance organizational adaptability. Relying on analyzing or projecting trends and extending what business leaders usually do is no longer enough to assure future success. When management is poorly prepared for the unexpected, businesses start getting into trouble.

Scenario planning, therefore, helps businesses keep themselves flexible and move quickly with market shifts. Scenario planning is a series of potential stories or possible alternate futures in which today’s decisions may play out. Such planning can help managers assess how they or their employees should respond in different potential situations.

How businesses can use novels

Unfortunately, scenario planning requires time and resources. And depending on its use, such as for an investigation, budgeting or legal matters, it can also require collecting sensitive data. That can include employees’ personal experiences of sexual, discriminatory or psychological harassment, suicide, mental health, drug abuse, etc.

The more sensitive the needed data is, the more difficult it is to collect while ensuring employee privacy. This is where literary texts come in.

(Helena Lopes/Unsplash)

As sources for possible future scenarios capable of providing strategic foresight, or producing alternative future plans, novels can also help businesses create dialogue on difficult and even taboo subjects.

Novels are, therefore, capable of helping managers become better, providing them with creative insight and wisdom. Science fiction can provide a means to explore morality tales, a warning of possible futures, in an attempt to help us avoid or rectify that future.

Brave new business world

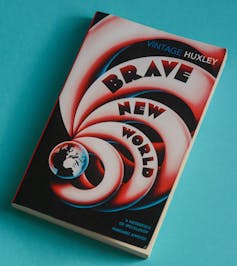

Our research

uses Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel Brave New World to explore possible scenarios related to situations that are usually kept confidential, such as employees’ mental health issues and drug use or abuse. We examined how employers encounter uncertainty around the impact that legalizing cannabis could have on the work environment, and ways to consider such potential effects.

Brave New World is set in a dystopian future and has been adapted numerous times, most recently into a 2020 TV series. It portrays a dystopic civilization whose members are shaped by genetic engineering and behavioural conditioning. Their happiness is maintained by government-sanctioned drug consumption. It is a world where countries are protected by walls that keep the undesired away — an eerily familiar scenario to Donald Trump’s promise of building a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

(Shutterstock)

By reading the novel, business managers can compare the world we live in today and the path our countries and corporations are on to the fictional events in the novel. This can help them pay attention to and address less comfortable, and sometimes often neglected, sensitive workplace issues that need to be considered when planning for the future.

For example, in Brave New World, the consumption of the drug “soma” becomes the norm upon which life is founded. When soma is taken away, individuals can no longer face their reality and they end up welcoming death.

Brave New World offers workplace leaders a look at what could happen if employees’ wellness, mental health or drug use are disregarded, and lead to isolation, absence, resignation or, in dire circumstances, suicide.

8-step action plan

To study sensitive workplace issues that could help generate new knowledge, lead to envisioning ways to act appropriately and develop future strategies, business managers can follow these steps:

- Form a team of managers and an HR representative who is aware of company policies and ethics protocols, and is in direct contact with employees.

- The team then decides which workplace issue(s) the organization needs to study.

- The team chooses a literary text, such as a novel, that discusses those issues.

- Each member of the team reads the literary text on their own before discussing it together in at least one session.

- The team researches the chosen workplace topics inside the organization and outside (for example, laws and regulations related to each issue).

- The team identifies insightful sections.

- The team analyzes the chosen extracts.

- The team writes a report with recommendations on workplace conditions and how best to improve them.

Reading has surged during lockdown. But literary works can provide us with more than a leisurely pastime. For businesses, novels represent a legitimate way to study the workplace, and this is accomplished by comparing the path our countries and corporations are on today to fictional events.![]()

Nada Elnahla, PhD Candidate, Sprott School of Business, Carleton University and Ruth McKay, Associate Professor, Management and Strategy, Sprott School of Business, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.