Hannah Copley, University of Westminster

For many, this year’s Valentine’s Day will be like no other. If you are spending the day apart from your loved ones, and don’t fancy the card selection at your local Tesco, writing a poem can be a more personal way to reach out and connect. Indeed, to paraphrase John Donne, “more than kisses, [poems] mingle souls”.

Here are some poems to take inspiration from, as well as some prompts to help you get that first line on the page.

Make a list

In her sonnet, How Do I Love Thee, Elizabeth Barrett Browning demonstrates the effectiveness of staying power when it comes to writing romance. After setting out to count the ways, the poem sticks determinedly to its opening concept – how do I love thee – answering the question from every possible angle, reaching to “the depth and breadth and height / My soul can reach”.

Read more:

Poems for long distant loves in lockdown

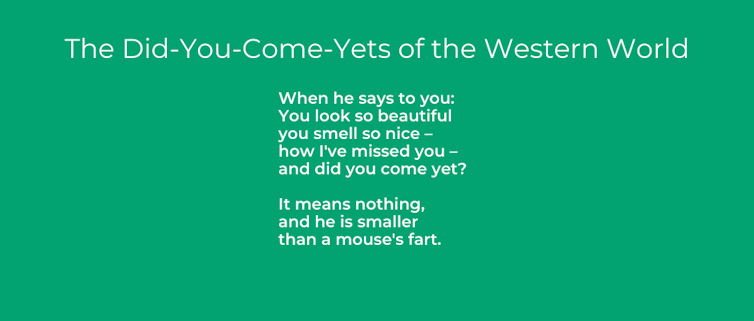

How do I love thee demonstrates how incorporating a list within a poem can make for a persuasive and intimate piece of writing. We see this again, in an altogether sillier way, in Ways of Making Love, by Hera Lindsay Bird. In her poem, Bird unfolds a surprising and decidedly unsexy list of similes to “answer” the instructional title of the poem:

Like a metal detector detecting another metal detector.

Like two lonely scholars in the dark clefts of the Cyrillic alphabet.

Like an ancient star slowly getting sucked into a black hole.

Whether it’s heartfelt or more lighthearted, a list poem is an opportunity to remember the quirks that make up a relationship. Half prayer, half receipt, it can quantify the seemingly unquantifiable, as the need to find the next answer to the opening question forces you to think creatively and explore beyond the obvious.

Why not begin with a title like “Each Thing You Do”, and challenge yourself to at least forty lines. Or perhaps you might want to answer Barrett Browning’s original question in light of our 2021 reality:

I love you further than two metres;

I love you beyond the limits of my daily walk.

Embrace desire

Ways of Making Love might not live up to the eroticism of its title, but Selima Hill’s Desire’s a Desire certainly delivers:

It taunts me

like the muzzle of a gun;

it sinks into my soul like chilled honey

packed into the depths of treacherous wounds;

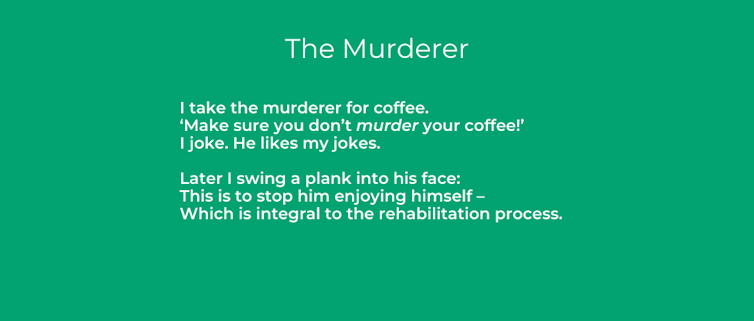

In this variation of the list poem, Hill takes longing as her starting point and recounts its effects in sensual, almost painful detail. Similarly, in Kim Addionzo’s For Desire, the poet celebrates what it is to want without restraint or guilt, whether that’s “the strongest cheese”, the “good wine”, or “the lover who yanks open the door / of his house and presses me to the wall”. In Fucking in Cornwall, Ella Frears embraces the less-than-glamorous realities of sex and desire:

The rain is thick and there’s half a rainbow

over the damp beach; just put your hand up my top.

It may not be the stuff of the big-budget period drama, but it’s joyful in its nostalgia for the awkward fumbling of first love, as well as of the rainy delights of the English seaside.

Each of these poems celebrates the power of declaring longing and need; of articulating the body and what it wants.

Be playful

Perhaps you’ll notice something familiar about the opening lines of Harryette Mullen’s Dim Lady:

My honeybunch’s peepers are nothing like neon. Today’s special at Red Lobster is redder than her kisser. If Liquid Paper is white, her racks are institutional beige. If her mop were Slinkys, dishwater Slinkys would grow on her noggin.

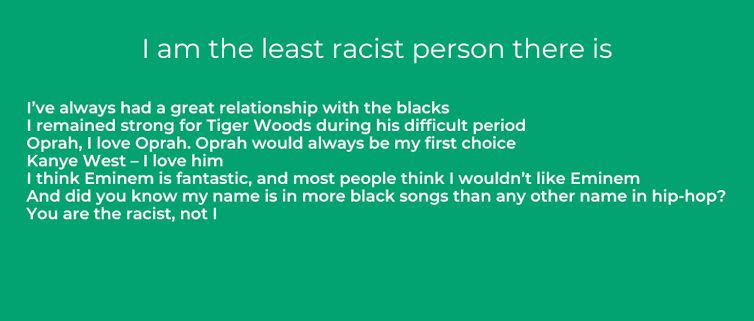

In this fast-paced ode, Mullen takes Shakespeare’s famous Sonnet 130 (“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”) — itself a parody — and effectively scribbles all over it. While she maintains the style of the original, she substitutes almost every word with a contemporary reference to mass consumer culture, rendering the whole declaration — and the love industry — joyfully ridiculous.

Dim Lady demonstrates the power of the re-write and celebrates the fact that poetry – like love – can be a playful and adaptable collaboration. Like the Zoom pub quiz and online escape room, Mullen’s word substitution is a game that can be played at whatever distance.

Why not each take Sonnet 130 and come up with your own versions using a different frame of reference. Types of plant? TV programmes? Biscuit brands? Then swap and compare results.

And remember, whatever style you decide to try this Valentine’s Day, keep in mind the poet Les Murray’s sage advice:

The best love poems are known

as such to the lovers alone.

When it comes to writing your own verse, remember, it’s the thought that counts.![]()

Hannah Copley, Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.