The link below is to an article that takes a look at 5 of the best poems of John Keats.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/23/john-keats-five-poets-on-his-best-poems-200-years-since-his-death

The link below is to an article that takes a look at 5 of the best poems of John Keats.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/23/john-keats-five-poets-on-his-best-poems-200-years-since-his-death

Richard Marggraf-Turley, Aberystwyth University

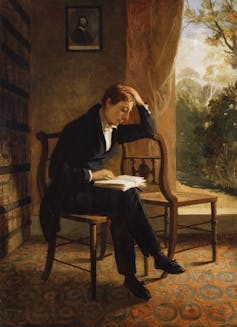

In John Keats’ poems, death crops up 100 times more than the future, a word that appears just once in the entirety of his work. This might seem appropriate on the 200th anniversary of the death of Keats, who was popularly viewed as the young Romantic poet “half in love with easeful death”.

Death certainly touched Keats and his family. At the age of 14, he lost his mother to tuberculosis. In 1818, he nursed his younger brother Tom as he lay dying of the same disease.

After such experiences, when Ludolph, the hero of Keats’ tragedy, Otho the Great, imagines succumbing to “a bitter death, a suffocating death”, Keats knew what he was writing about. And then, aged just 25, on February 23 1821, Keats himself died of tuberculosis in Rome.

His preoccupation with death doesn’t tell the whole story, however. In life, Keats was vivacious, funny, bawdy, pugnacious, poetically experimental, politically active, and above all forward-looking.

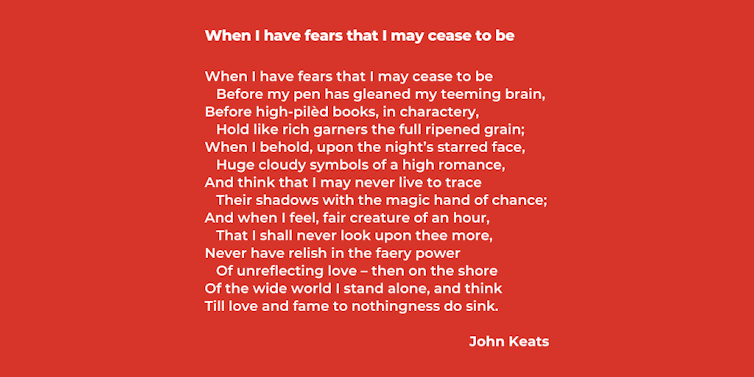

He was a young man in a hurry, eager to make a mark on the literary world; even if – as a trained doctor – he was all too conscious of the body’s vulnerability to mortal shocks. These two very different energies coalesce in one of his best loved poems, written in January 1818 when the poet was in the bloom of health:

When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be is a poem of personal worry, according to biographer Nicholas Roe. In it, Keats is anxious that he won’t have time to achieve poetic fame or fall in “unreflecting love”, and these fears and self-doubts take him to the brink.

But as brinks go, this one doesn’t seem all that bad. The poem is romantic with a small “r” – wide-eyed, dramatic, sentimental – its vision of finality, of nothingness, gorgeous in its desolation, and all-importantly painless. Who can read those final lines without themselves feeling a pull to swooning death, half in love with it, as Keats professed to be?

That’s what I used to think, at any rate. Lately, in the pandemic, I’ve begun to read this poem rather differently. Lensed through long months of lockdown, the sonnet’s existential anxieties seem less abstract, grand and performative, and more, well, human.

It’s a poem that will resonate with the youth who are cooped up indoors, physically isolated, unable to meet and mingle, agonisingly aware of weeks slipping by, opportunities missed, disappointments mounting. This poem has made me almost painfully empathetic towards their plight.

The sonnet’s fears of a future laid to waste are shared by whole generations whose collective mental health is under siege. In his last surviving letter, written two years after the sonnet while dying in Rome, Keats records a “feeling of my real life having past”, a conviction that he was “leading a posthumous existence”. How many of us are experiencing similar thoughts at the moment?

Of all the Romantics, Keats perhaps knew most about mental suffering. He grew up in Moorgate, just across from Bethlem Hospital, which was known to London and the world as Bedlam. Before he turned to poetry, Keats trained at Guy’s hospital, London, where he not only witnessed first-hand the horrors of surgery in a pre-anaesthetic age but also tended to patients on what was called the lunatic ward.

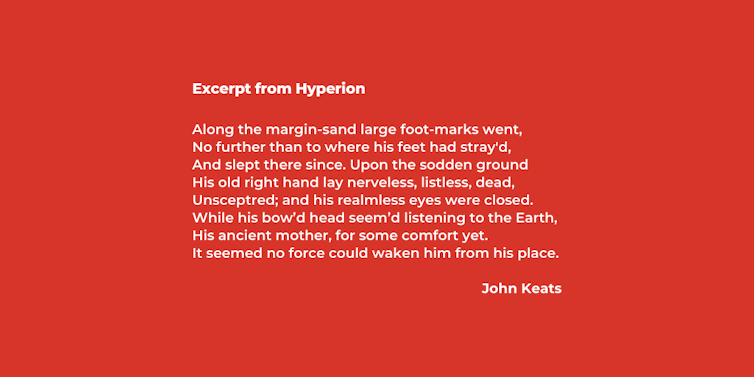

It was all too much for him. Traumatised by the misery and pain he felt he could do little to alleviate, in 1816 he threw medicine in for the pen. His experiences at Guy’s, though, and the empathy he developed there, found their way into his writing. For instance, in Hyperion, his medical knowledge helps him to inhabit the catatonic state of “gray-hair’d Saturn”, who sits in solitude, “deep in the shady sadness of a vale”, despairing after being deposed by the Olympian gods. The vignette is a moving image of isolation and enervation that speaks to us today:

As for lockdown, Keats was no stranger to its pressures and deprivations. During periods of illness in Hampstead in 1819 – precursor symptoms of tuberculosis – he was reluctant to venture out, isolating himself. In October 1820, he set sail for Italy in the hope warmer climes would save his lungs. On arrival, his ship was put into strict quarantine for ten days. In letters to his friends, Keats described being “in a sort of desperation”, adding, “we cannot be created for this sort of suffering”.

Keats was a poet of his age, his own social, cultural and medical milieu. And yet, on the bicentenary of his death, he’s also – more than ever, perhaps – a poet of ours. A poet of lockdown, frustration, disappointment, fears … and even hope.

Because even in those last, scarcely imaginable weeks in Rome, 200 years ago, holed up in a little apartment at the foot of the Spanish Steps, he never quite gave up on the future, never relinquished his dreams of love and fame.![]()

Richard Marggraf-Turley, Professor of English Literature, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elisabeth Gruner, University of Richmond

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Do authors really put deeper meaning into poems and stories – or do readers make it up? Jordan, 14, Indianapolis, Indiana

One of my favorite novels is “Charlotte’s Web,” the famous story of a friendship between a pig and a spider.

I often talk about this novel with my students studying children’s literature. At some point, someone always asks about “deeper meaning.” Is it really a story of, say, the cycle of death and rebirth? Or the importance of friendship? Or the significance of writing?

Or is it just a story of life in the barn, with talking animals?

In a way, it doesn’t matter. Because every writer is also a reader, and that means that whatever a writer puts into a story probably came from somewhere else, whether it’s another story, or a poem, or their own life experience.

And readers, too, will bring their own experience – of other stories, other poems and life – and that will direct their interpretation of what they absorb. We can see one example of this if we look at the spider in “Charlotte’s Web.”

That spider, Charlotte, is based on a real spider. We know this because E.B. White drew pictures of spiders, studied them and made sure to be as accurate as he could when he wrote about them.

But, to a reader she may also represent Arachne, the talented weaver who challenged the goddess Athena and was changed into a spider for her pride. Or she may be the “noiseless patient spider” of Walt Whitman’s poem, who flings out thread-like filaments as the poet flings out words.

She may also be the spider who weaves “the silken tent” of Robert Frost’s poem. Maybe we’ll think about how the spider, like a human storyteller, generates something seemingly out of nothing, which makes her web miraculous.

Each of these spiders symbolizes different things. When we read about her, then, we may think of all those other spiders. Or we may just think about the spider we saw on our own front porch that morning, weaving her own web.

As the writer Philip Pullman said, “The meaning of a story emerges in the meeting between the words on the page and the thoughts in the reader’s mind.”

What Pullman is suggesting, then, is that it’s up to readers to make the meaning they want out of the stories they hear and the books they read.

It’s a powerful statement: We are in charge.

This doesn’t mean that anything goes. Meanings come from context, from convention, from older stories and from previous usage. But it’s up to us to interpret what we read and to make the case for how we’re doing it.

Or, as the novelist John Green writes of his books, “They belong to their readers now, which is a great thing – because the books are more powerful in the hands of my readers than they could ever be in my hands.”

What we do with the books we read matters, Green tells us. It’s up to us to make the meaning and up to us to decide what to do with that meaning once we’ve made it.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Elisabeth Gruner, Associate Professor of English, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Laura Varnam, University of Oxford

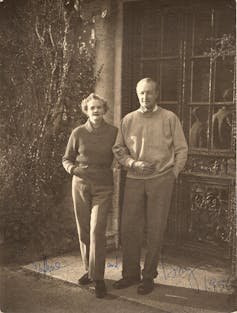

Daphne du Maurier remains one of the 20th century’s most popular and enigmatic writers, her life captivating readers as much as her works, as the most recent biography, Manderley Forever by Tatiana de Rosnay, has shown. Her literary reputation is also finally on the rise and, although her most popular novel Rebecca has often overshadowed her wide-ranging achievements as a writer, the celebration of its 80th anniversary last year reinforced Du Maurier’s place in the canon of English Literature as a serious and influential author.

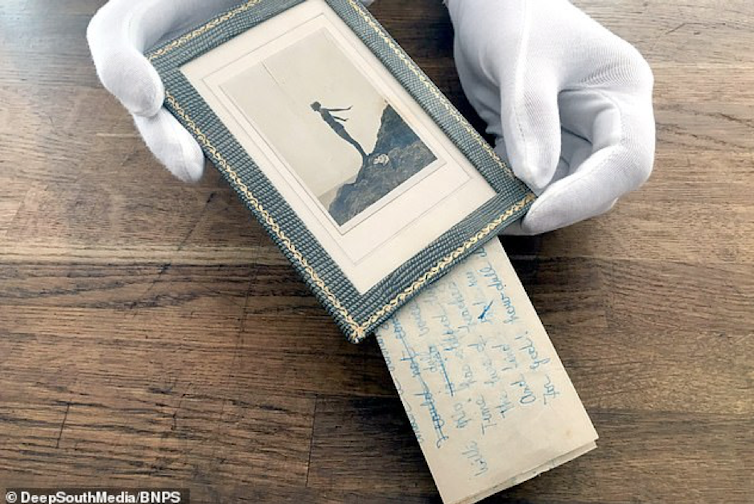

This will be aided by the recent discovery of unknown poems, written early in her writing career, hidden behind a stunning photograph of the young Du Maurier in a bathing costume on the rocks, poised to take flight into the sea that was such an inspiration to her work.

The poems were discovered by auctioneer Roddy Lloyd of Rowley’s auction house, Ely, as he prepared the archive of Du Maurier materials belonging to the late Maureen Baker-Munton for auction on April 27. Baker-Munton was PA to Daphne’s husband, Lt Gen Sir Frederick “Boy” Browning and she became a close and important friend to the Du Maurier Browning family, as expert Ann Willmore explains on the Du Maurier website.

Du Maurier is still primarily known as a novelist – as well as the bestseller Rebecca she is also rightly revered for the great Cornish novels, Jamaica Inn (1936), Frenchman’s Creek (1941) and My Cousin Rachel (1951). But, as I argue in the book I am writing on Du Maurier, she was a far more versatile, wide-ranging, and experimental writer than is currently recognised. Du Maurier wrote plays, short stories and biographies throughout her career but she was also a poet, as her son Kits Browning explained to me when we spoke over the telephone recently.

Read more:

Du Maurier’s Rebecca at 80: why we will always return to Manderley

The newly discovered poems were written when Du Maurier was honing her craft as a writer in the late 1920s. At that stage she was primarily writing short stories but, as Browning told me: “My mother wrote poetry throughout her life and career.” Indeed Du Maurier often used poetry as a way of exploring an experience or emotion or testing out a character before then expanding on her ideas in a short story or novel. One of the newly discovered poems focuses on loneliness:

When I was ten, I thought the greatest bliss,

would be to rest all day upon hot sand under a burning sun…

time has slipped by, and finally I’ve known,

The lure of beaches under exotic skies,

and find my dreams to be misguided lies,

For God! How dull it is to rest alone.

Du Maurier’s work is preoccupied by the difference between fantasy and reality – and the dangers of dreaming – and her work repeatedly returns to the tension between the desire for independence and the need for companionship and human contact.

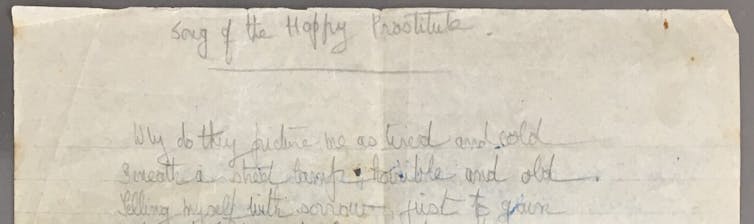

Another poem: Song of the Happy Prostitute, portrays a woman who is frustrated with the way her profession is represented.

Why do they picture me as tired and old…

selling myself with sorrow,

just to gain a few dull pence to shield me from the rain.

What on first sight might seem an unusual, even controversial, topic for the young writer in fact reflects the dominant themes of her early work, as Ann Willmore, of Bookends of Fowey, explained to me recently. Willmore discovered the unpublished Du Maurier short story The Doll in which a young woman, suggestively named Rebecca, protects her personal independence by keeping a sex doll. “The Happy Prostitute poem fits in with Daphne’s interests in gender and sexuality, especially in her early work, and she did seem to want to shock her readers”, Willmore told me.

The poem also, in my view, relates to two early short stories from the same period of Du Maurier’s life in which she created the character of a prostitute called Mazie who boldly claimed that her work enabled her to be independent. “I’m free, I don’t owe anything to no one, I belong to myself”, Mazie declares in the short story Piccadilly. Growing up in the 1920s, when the freedom and autonomy of women was increasingly a topic for public debate, Du Maurier’s choice of subject matter reflects the concerns of her day.

Du Maurier was a very privileged young woman, growing up in the grandeur of Cannon Hall in Hampstead – but her background was theatrical and Bohemian, as the daughter of celebrated actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and stage actress Muriel Beaumont. And, as her son Kits Browning stressed, she was an avid reader and gained much imaginative experience of the world from the books she devoured as a teenager.

As to why the poems were hidden behind the photograph – either by Du Maurier herself or someone else – we are unlikely ever to find out. Browning told the Daily Telegraph that perhaps she did not want her parents to read them. Perhaps the Happy Prostitute found fuller expression in the Mazie short stories.

These newly discovered poems shed important light on Du Maurier’s early work and writing practice. Still often dogged by the incorrect label of “romantic novelist”, these poems highlight the important themes of independence, gender, and sexuality that were to fascinate Du Maurier throughout her career, in both prose and poetry. They show her boldness, spirit, and strength, just like the photograph behind which they were concealed for all these years.![]()

Laura Varnam, Lecturer in English Literature, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.