Chris Pak, Swansea UniversityYou see the forest of cranes before you reach the coast. In the heat’s haze, machinery resounds in the middle distance, shifting and tamping dirt with earth-shattering force. Beyond the construction site, the sea sparkles under the Sun, traversed by ships old and new. It seems the whole city takes its cue from the coast – there is always so much being built, demolished and rebuilt.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

Those in power push ahead with their enduring programme to reshape the world by building new land. This is a society that is being transformed for a particular vision of the future: to build new worlds able to meet the challenges of a soaring population, more space and new modes of living. But what kind of future is being built, and at what cost?

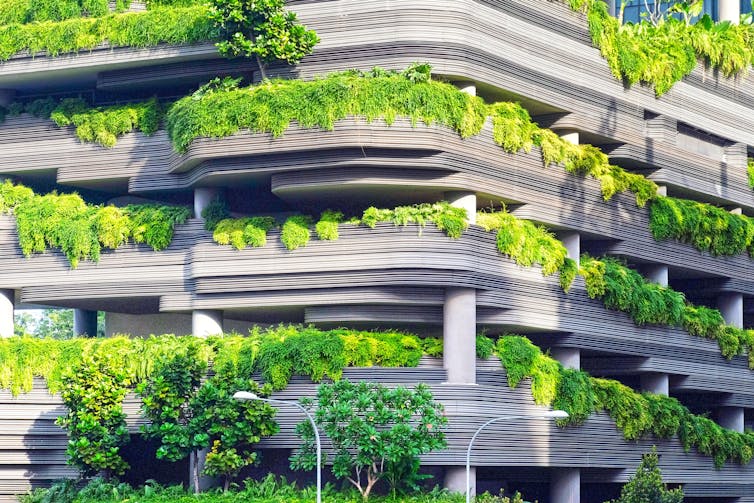

This isn’t science fiction. This is the real story of land reclamation in 1980s-90s Hong Kong, where I grew up. Land reclamation involves the filling of water bodies with soil to extend land or create artificial islands. Housing and infrastructure on the scale seen in Hong Kong is only possible because of how much land – over 70km² of it – was reclaimed. But this has come at a cost to people, biodiversity and the integrity of wildlife habitats alike.

It was during my childhood in this city, part of which was so recently submerged beneath the ocean, that I first began to speculate about the drastic ways we transform space – and the unforeseen impacts this has.

As a child immersed in science fiction classics such as Frank Herbert’s Dune, I quickly realised that fiction can help us consider, imagine, and work through these unforeseen impacts. And so it is no surprise that climate fiction – or “cli-fi” – has quickly become a recognised genre in recent years. From Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour to Omar El Akkad’s American War, people are clearly interested in imagining possible futures as a way of considering how we are going to get ourselves out of this mess.

If there is something that we can be fairly sure of, it is that the future will be radically different to what we had imagined, and that it will demand adjustment. This is why authors of science fiction are consulted by organisations and governments: to help us think about the risks and challenges of the future in ways inaccessible to other disciplines. As COP26, the delayed 2020 UN climate change conference in Glasgow, approaches we urgently need more of this imaginative impulse.

Science fiction has certainly already played a part in this narrative. Harnessing the Sun’s energy has a long history in science fiction, and Arthur C. Clarke is often credited with coming up with the idea of the solar cell-powered geostationary communications satellite. NASA’s satellite system, meanwhile, is crucial for monitoring climate change and can plausibly be traced back, in part, to science fiction’s capacity for thinking about worlds and systems. And of course, spaceships and space stations – indeed, our expansion into space – is an invention of science fiction.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. This story was commissioned by The Conversation’s Insights team. More.

Inspired by my early days in Hong Kong, I went on to shape a career researching science fiction with a focus on technical systems that transform the planet we live on: the idea of terraforming and geoengineering. If terraforming is the modification of other planets to enable habitation by life on Earth, geoengineering can be defined as the planetary modification of the Earth – such as the deliberate intervention in the climate system.

As the controversial debate about geoengineering becomes increasingly urgent given the catastrophic failure to curb emissions, science fiction about terraforming and geoengineering can help us imagine possible configurations of solutions to the climate crisis and their implications. A closer look at this particular example will also show why embracing this form of thinking is so crucial for the climate crisis more generally too.

The power of storytelling

Proposals for geoengineering and terraforming are informed both by history and by the stories we tell one another. What science fiction can do is imagine and think through the political, as well as the scientific, implications of the technological choices we make. Science fiction stories speculate on, diagnose and illustrate the experiences and the problems wrapped up in global debates about mitigation and adaptation.

The aim of science fiction is not to solve society’s problems (though specific works of science fiction do offer solutions that we as readers are invited to critique, revise, advocate for, and even adopt); nor is science fiction about prediction. We therefore shouldn’t evaluate science fiction according to its success or failure in this regard. Rather, the role of science fiction is to speculate on possibilities.

Romain Tordo/Unsplash, FAL

Science fiction, then, shouldn’t be read in isolation. The fictional space is an imaginative realm for testing ideas and values, and for attempting to imagine futures that could inform our societies now. The genre seeks to push beyond the assumptions of a singular time and place by providing a range of alternative ways of conceiving ideas, contexts and relationships. Science fiction asks to be challenged; it asks for us to hold one story up against another, to consider and interrogate the worlds portrayed and what they might tell us about our stances on crucial contemporary issues.

Reading such fiction can help us to think speculatively beyond the technical aspects of adaptation, mitigation and, indeed, intervention, and to understand the stances that we as people and as societies take toward these concerns.

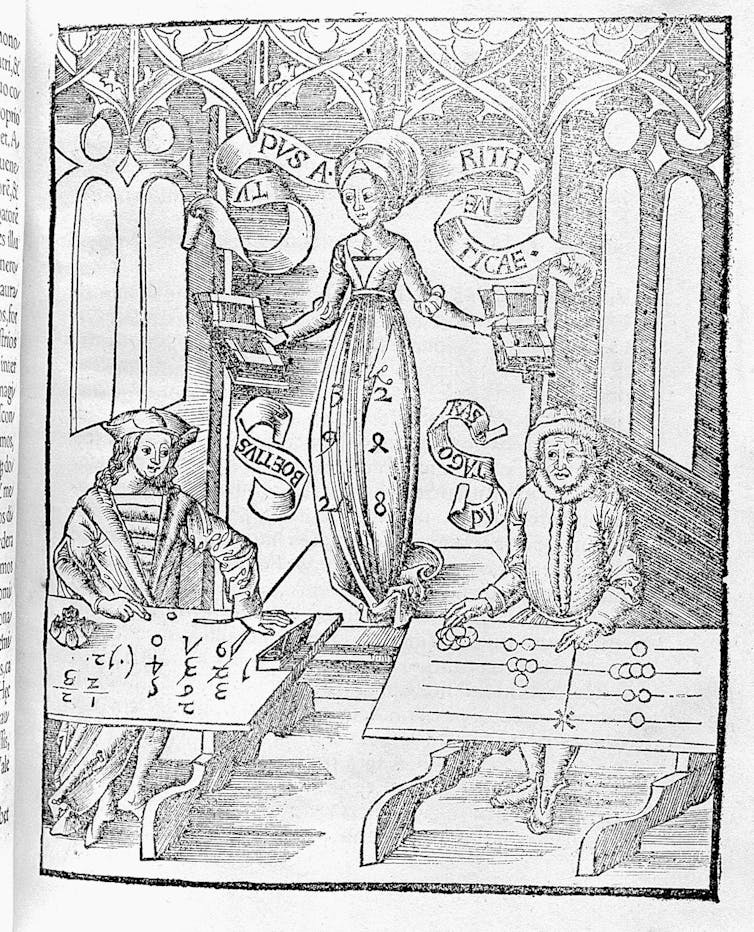

This is the idea behind my book, in which I survey the history of stories about terraforming, geoengineering, space and climate change. What science fiction teaches us is that technologies are not simply technical systems. Science is not simply a theoretical and technical endeavour. Rather, the practice of science and the development of technologies are also fundamentally social and cultural. This is why many researchers use the word “sociotechnical” to describe technological systems.

A geoengineered planet

In the real – policy – world, fictions inform the imagination. Some imagine a future world covered by machines sucking CO₂ out of the air and pumping it into the porous rock below. Others imagine one powered by a portfolio of vast wind and solar farms, hydroelectric and geothermal plants. Some imagine business largely continuing as usual, with only moderate changes in how we produce and use energy, and little to no change to how we organise our economies and our lives.

And some suggest we send planes into the stratosphere, pumping out particulates that will reflect sunlight back into space and turn the sky white.

It is this last vision, solar radiation management (SRM), that has been the subject of particularly intense debate. SRM involves controlling the amount of sunlight trapped in Earth’s atmosphere. A number of scientists, including Ken Caldeira and David Keith (sometimes referred to as the “geoclique”) advocate for further research into SRM, but they are strongly opposed by various pressure groups.

Bill McGuire, a patron of Scientists for Global Responsibility and Emeritus Professor of Earth Sciences at UCL, recently wrote a science fiction novel, Skyseed (2020), which imagines the terrifying failure of a nanotech-based approach to solar radiation management. This novel describes the impossibility – given our current state of knowledge – of foreseeing the consequences of this speculative technology.

Proposals for solar radiation management vary enormously, but the most common forms involve brightening marine clouds or injecting particles into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight away from the Earth. Doing so, it is proposed, would help to cool the Earth, though it would do nothing to remove carbon and other carbon equivalent gases from the atmosphere, nor would it address ocean acidification.

Read more:

Climate repair: three things we must do now to stabilise the planet

More extravagant ideas include building sunshades in space and placing them in various orbital configurations. If this idea sounds like it comes straight out of a science fiction novel, that’s because it does: such orbital mirrors feature in James Oberg’s 1981 work New Earths and Lois McMaster Bujold’s 1998 novel Komarr.

Transforming planets

But what can terraforming tell us about geoengineering and Earth? The idea of transforming places beyond Earth – planets or other spatial bodies – to make them more amenable to human life has been a mainstay of science fiction for decades. The necessity of maintaining life support systems in space habitats and spaceships draws on the same science that underpins technologies for addressing climate change. Such stories pose many pertinent questions that we should heed as we consider next steps on Earth – or beyond it.

In its broadest sense, terraforming refers to transforming other planets or cosmic bodies so that life from Earth can live there. Entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, have brought terraforming and the colonisation of Mars to our imagination through an ambitious project to put people on the planet within the decade. Musk is not alone: other entrepreneurs such as Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic) and Jeff Bezos (Blue Origins) are also competing to exploit space and get humankind out there.

Read more:

Billionaire space race: the ultimate symbol of capitalism’s flawed obsession with growth

Contemporary visions of terraforming Mars must contend with recent assessments that show it is not possible to terraform the planet with present day technology, given the lack of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that would enable an atmosphere to be created on Mars. But scientific research into terraforming continues to carve out a space for its future possibility.

Nicolas Lobos/Unsplash, FAL

Although it is the subject of current scientific research, the word “terraforming” was in fact coined by science fiction writer Jack Williamson (writing as Will Stewart) in the 1942 short story, Collision Orbit, set on a terraformed asteroid. The story describes terraforming technologies that include a “paragravity installation” sunk into the heart of the asteroid, which provides some gravity. Oxygen and water, meanwhile, are generated from mineral oxides, a process that releases “absorptive gases to trap the feeble heat of the far-off Sun”.

In the story, the greenhouse effect is harnessed to make other cosmic bodies habitable. What makes terraforming possible here are new ways of manipulating atomic matter. But Williamson is also concerned with the unintended consequences of new inventions and new ways of generating energy. New energy systems make terraforming feasible for small groups and large institutions alike, promising a re-configuration of power throughout the solar system by the story’s end.

Lessons from fiction for the future

I’ve focused here on the ideas of geoengineering and terraforming because they represent the most outlandish theories or proposals when it comes to potential “solutions” to the climate crisis. But of course, everything I’ve written applies just as much to thinking about less grandiose proposals.

The questions and speculations offered by science fiction are endless, and it would be a fool’s errand to attempt to outline those that are the most pertinent, or important, or relevant to COP26. So instead I’d like highlighting those books that have stayed with me the most in my time working in this area, and explain why I think they might prove fruitful food for thought for anyone attending, debating, or simply following COP26.

1. Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest (1972).

This short novel by science fiction heavyweight Ursula K. Le Guin describes a forest world, populated by an indigenous society, that early on in the novel is occupied and aggressively deforested to provide Earth with wood. This is not simply a technical project. It is also social because it involves the complete transformation of the indigenous society, who are violently gang-pressed to provide a freely exploitable labour force. It is also social insofar as this supply chain is oriented to the demands and desires of those on Earth.

We might see echoes of this story in James Cameron’s film Avatar (2009); only, in Avatar the target for extraction is “unobtainium”. In Herbert’s iconic novel Dune, it’s a substance called “geriatric spice mélange”. It’s not important what these resources are, but that they are scarce and valuable in the stories’ worlds.

Portrayals of extensive afforestation and deforestation are a form of terraforming or geoengineering because they transform the planet’s ability to regulate its climate. This isn’t addressed directly in Le Guin’s novel; but Le Guin does explore the issue of terraforming in her 1974 novel The Dispossessed, which focuses on the political and economic relationship between an anarchist state on a moon called Anarres and its historical home planet, Urras. This novel explores what life might look like on a Moon that has long been undergoing terraformation.

What these examples tell us is that, in some contexts, afforestation or deforestation that transforms societies and their environments function as a form of terraforming or geoengineering. We must recognise prior claims to the land and work with communities to develop an ethics of care for these environments that resist aggressive exploitation.

2. Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy (1992-1996)

Perhaps the author who has most consistently explored contemporary debates about climate change is Kim Stanley Robinson.

Named the 2008 TIME “Hero of the Environment”, Robinson addresses climate change politics in works set on Earth and the solar system. I’ve written extensively about Robinson’s work, which speculates on a portfolio of sciences and technologies to supplement the creation of new ways of living centred on social and ecological justice. Most importantly, Robinson ties these technologies to the communities being portrayed, and traces the struggles and injustices that such developments risk.

Robinson imagines the terraformation of Mars in his trilogy Red Mars (1992), Green Mars (1993) and Blue Mars (1996). A host of technologies appear, including orbital mirrors, referred to as solettas, technologies for engineering soil and biologically engineered lichens to transform the atmosphere, among many others.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the Mars trilogy is the consistent reflection on the vision for transformation: for whom is the planet being transformed? Corporate interests on Earth, or the entirety of the Martian population? And what relationship does the transformation of Mars bear for the peoples on Earth?

As one of the key members of the terraforming project on Mars, the scientist Sax Russell’s technocratic, top-down approach to the terraformation of Mars undergoes a sea change after a traumatic brain injury during a Martian revolution. This injury prompts him to reflect on language and communication and leads him to understand that the technical approach that he had thus far adopted — an approach that erases the perspectives and experiences of his fellow Martians — is insufficient for building a truly open society. In his own imperfect way, he begins to move toward an understanding of science as a firmly sociotechnical system, and to realise that the human element cannot be ignored.

The fictional adventures of Russell might as well inform our own response to climate change. By hearing only the voices of specialists and politicians, other avenues for addressing climate change might be overlooked. Worse, we may inadvertently lock ourselves into a technological system that cannot hope to address the effects of climate change, or which may exacerbate the precariousness of many peoples across the globe.

Science fiction offers ways to discuss speculative technologies without presenting them as ready made technological fixes, enabling wider public deliberation about our approach to climate change. Fiction asks crucial questions, revises and reconsiders aspects of science and society in relation to their contemporary moment. But it also transmits a way of thinking – it identifies our assumptions about the worlds we want to live in and challenges dominant narratives about climate change. Most importantly, it offers a range of possible technological solutions, which could and should inform our response to the climate crisis.

3. Ian McDonald’s Luna Trilogy (2015-2019)

McDonald considers the exploitation of resources and people, along with the extension of financial speculation to all aspects of life on the colonised Moon in his trilogy Luna: New Moon (2015), Luna: Wolf Moon (2017) and Luna: Moon Rising (2019).

In this story of power and the exploitation of the Moon’s resources, families who control key industries on the Moon struggle for dominance against the backdrop of an Earth that is adapting to climate change. The trilogy imagines and interrogates the extension of the logic of development outward to the solar system and encourages readers to think about the inevitable economic and political clashes this will bring.

Science fiction can help us think about our own stories of climate mitigation and adaptation. Such stories are experiments in envisioning future possibilities and creating solutions to future problems. Central to many of these visions is an emphasis on social and ecological justice, and an awareness of the dangers of erasing populations from the story.

It is true that attempts to imagine the future are the product of utopian thinking – but don’t imagine for a moment that utopian in this sense equates to a naive idealism. Rather, utopian thinking is a commitment to working through the difficulties and impasses of our contemporary moment without losing sight of the possible futures that we imagine and would like to create.

What makes science fiction valuable in our efforts against climate change is that it does not offer us a final word, but rather invites an open ended exploration and experimentation with stories and ideas. Science fiction encourages us to build worlds and to question the worlds that we are building. It asks us to choose a future from a range of possibilities and to put in the work to create it. Science fiction was crucial in helping me make sense of the radical transformations of 20th century Hong Kong and the UK, and it led to my engagement with the politics of climate change. This is precisely the work of public deliberation and engagement that is crucial as we move toward and beyond COP26.

For you: more from our Insights series:

- There aren’t enough trees in the world to offset society’s carbon emissions – and there never will be

- Drugs, robots and the pursuit of pleasure – why experts are worried about AIs becoming addicts

- Billionaire space race: the ultimate symbol of capitalism’s flawed obsession with growth

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Chris Pak, Lecturer in English Literature, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.