The link below is to an article that looks at it being OK to quit reading a book.

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/essay/article/why-its-okay-to-quit-a-book/

The link below is to an article that looks at it being OK to quit reading a book.

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/essay/article/why-its-okay-to-quit-a-book/

Emma Smith, University of Oxford

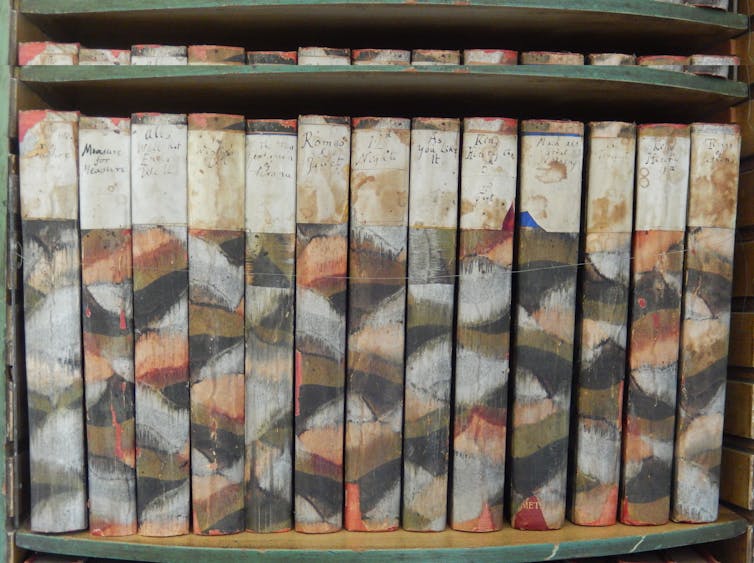

In recent years the orthodoxy that Shakespeare can only be truly appreciated on stage has become widespread. But, as with many of our habits and assumptions, lockdown gives us a chance to think differently. Now could be the time to dust off the old collected works, and read some Shakespeare, just as people have been doing for more than 400 years.

Many people have said they find reading Shakespeare a bit daunting, so here are five tips for how to make it simpler and more pleasurable.

If your edition has footnotes, pay no attention to them. They distract you from your reading and de-skill you, so that you begin to check everything even when you actually know what it means.

It’s useful to remember that nobody ever understood all this stuff – have a look at Macbeth’s knotty “If it were done when ‘tis done” speech in Act 1 Scene 7 for an example (and nobody ever spoke in these long, fancy speeches either – Macbeth’s speech is again a case in point). Footnotes are just the editor’s attempt to deny this.

Try to keep going and get the gist – and remember, when Shakespeare uses very long or esoteric words, or highly involved sentences, it’s often a deliberate sign that the character is trying to deceive himself or others (the psychotic jealousy of Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, for instance, expresses itself in unusual vocabulary and contorted syntax).

The layout of speeches on the page is like a kind of musical notation or choreography. Long speeches slow things down – and, if all the speeches end at the end of a complete line, that gives proceedings a stately, hierarchical feel – as if the characters are all giving speeches rather than interacting.

Short speeches quicken the pace and enmesh characters in relationships, particularly when they start to share lines (you can see this when one line is indented so it completes the half line above), a sign of real intimacy in Shakespeare’s soundscape.

Blank verse, the unrhymed ten-beat iambic pentamenter structure of the Shakespearean line, varies across his career. Early plays – the histories and comedies – tend to end each line with a piece of punctuation, so that the shape of the verse is audible. John of Gaunt’s famous speech from Richard II is a good example.

This royal throne of kings, this sceptered isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars.

Later plays – the tragedies and the romances – tend towards a more flexible form of blank verse, with the sense of the phrase often running over the line break. What tends to be significant is contrast, between and within the speech rhythms of scenes or characters (have a look at Henry IV Part 1 and you’ll see what I mean).

Shakespeare’s plays aren’t novels and – let’s face it – we’re not usually in much doubt about how things will work out. Reading for the plot, or reading from start to finish, isn’t necessarily the way to get the most out of the experience. Theatre performances are linear and in real time, but reading allows you the freedom to pace yourself, to flick back and forwards, to give some passages more attention and some less.

Shakespeare’s first readers probably did exactly this, zeroing in on the bits they liked best, or reading selectively for the passages that caught their eye or that they remembered from performance, and we should do the same. Look up where a famous quotation comes: “All the world’s a stage”, “To be or not to be”, “I was adored once too” – and read either side of that. Read the ending, look at one long speech or at a piece of dialogue – cherry pick.

One great liberation of reading Shakespeare for fun is just that: skip the bits that don’t work, or move on to another play. Nobody is going to set you an exam.

On the other hand, thinking about how these plays might work on stage can be engaging and creative for some readers. Shakespeare’s plays tended to have minimal stage directions, so most indications of action in modern editions of the plays have been added in by editors.

Most directors begin work on the play by throwing all these instructions away and working them out afresh by asking questions about what’s happening and why. Stage directions – whether original or editorial – are rarely descriptive, so adding in your chosen adverbs or adjectives to flesh out what’s happening on your paper stage can help clarify your interpretations of character and action.

One good tip is to try to remember characters who are not speaking. What’s happening on the faces of the other characters while Katherine delivers her long, controversial speech of apparent wifely subjugation at the end of The Taming of the Shrew?

The biggest obstacle to enjoying Shakespeare is that niggling sense that understanding the works is a kind of literary IQ test. But understanding Shakespeare means accepting his open-endedness and ambiguity. It’s not that there’s a right meaning hidden away as a reward for intelligence or tenacity – these plays prompt questions rather than supplying answers.

Would Macbeth have killed the king without the witches’ prophecy? Exactly – that’s the question the play wants us to debate, and it gives us evidence to argue on both sides. Was it right for the conspirators to assassinate Julius Caesar? Good question, the play says: I’ve been wondering that myself.

Returning to Shakespeare outside the dutiful contexts of the classroom and the theatre can liberate something you might not immediately associate with his works: pleasure.![]()

Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elaine Reese, University of Otago

Humans are innately social creatures. But as we stay home to limit the spread of COVID-19, video calls only go so far to satisfy our need for connection.

The good news is the relationships we have with fictional characters from books, TV shows, movies, and video games – called parasocial relationships – serve many of the same functions as our friendships with real people, without the infection risks.

Read more:

Say what? How to improve virtual catch-ups, book groups and wine nights

Some of us already spend vast swathes of time with our heads in fictional worlds.

Psychologist and novelist Jennifer Lynn Barnes estimated that across the globe, people have collectively spent 235,000 years engaging with Harry Potter books and movies alone. And that was a conservative estimate, based on a reading speed of three hours per book and no rereading of books or rewatching of movies.

This human predilection for becoming attached to fictional characters is lifelong, or at least from the time toddlers begin to engage in pretend play. About half of all children create an imaginary friend (think comic strip Calvin’s tiger pal Hobbes).

Preschool children often form attachments to media characters and believe these parasocial friendships are reciprocal — asserting that the character (even an animated one) can hear what they say and know what they feel.

Older children and adults, of course, know that book and TV characters do not actually exist. But our knowledge of that reality doesn’t stop us from feeling these relationships are real, or that they could be reciprocal.

When we finish a beloved book or television series and continue to think about what the characters will do next, or what they could have done differently, we are having a parasocial interaction. Often, we entertain these thoughts and feelings to cope with the sadness — even grief — that we feel at the end of a book or series.

The still lively Game of Thrones discussion threads or social media reaction to the death of Patrick on Offspring a few years back show many people experience this.

Some people sustain these relationships by writing new adventures in the form of fan fiction for their favourite characters after a popular series has ended. Not surprisingly, Harry Potter is one of the most popular fanfic topics. And steamy blockbuster Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction for the Twilight series.

So, imaginary friendships are common even among adults. But are they good for us? Or are they a sign we’re losing our grip on reality?

The evidence so far shows these imaginary friendships are a sign of well-being, not dysfunction, and that they can be good for us in many of the same ways that real friendships are good for us. Young children with imaginary friends show more creativity in their storytelling, and higher levels of empathy compared to children without imaginary friends. Older children who create whole imaginary worlds (called paracosms) are more creative in dealing with social situations, and may be better problem-solvers when faced with a stressful event.

As adults, we can turn to parasocial relationships with fictional characters to feel less lonely and boost our mood when we’re feeling low.

As a bonus, reading fiction, watching high-quality television shows, and playing pro-social video games have all been shown to boost empathy and may decrease prejudice.

We need our fictional friends more than ever right now as we endure weeks in isolation. When we do venture outside for a walk or to go the supermarket and someone avoids us, it feels like social rejection, even though we know physical distancing is recommended. Engaging with familiar TV or book characters is one way to rejuvenate our sense of connection.

Plus, parasocial relationships are enjoyable and, as American literature professor Patricia Meyer Spacks noted in On Rereading, revisiting fictional friends might tell us more about ourselves than the book.

So cuddle up on the couch in your comfiest clothes and devote some time to your fictional friendships. Reread an old favourite – even one from your childhood. Revisiting a familiar fictional world creates a sense of nostalgia, which is another way to feel less lonely and bored.

Read more:

Couch culture – six months’ worth of expert picks for what to watch, read and listen to in isolation

Take turns reading the Harry Potter series aloud with your family or housemates, or watch a TV series together and bond over which characters you love the most. (I recommend Gilmore Girls for all mothers marooned with teenage daughters.)

Fostering fictional friendships together can strengthen real-life relationships. So as we stay home and save lives, we can be cementing the familial and parasocial relationships that will shape us – and our children – for life.![]()

Elaine Reese, Professor of Psychology, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that reports on a report that found ebook readers read more than other readers.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/people-who-read-ebooks-read-more

The link below is to an article that reports on a report that found digital readers are more likely to be writers than print only readers. The article contains a link to the report concerned.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/digital-readers-are-more-likely-to-be-writers-than-print-only-readers-says-a-new-report/

Kate Flaherty, Australian National University

Every year about 150 students enrol in the introductory English literature course at the Australian National University, which I teach. The course includes works by Shakespeare, Austen, Woolf and Dickens.

I know what these books did for me as a student 20 years ago, but times have changed. I am curious to discover what reading these old books does for young people today.

Last year, 2019, saw the first cohort of students who were born in or beyond 2000 – the so-called digital generation. These students have grown up in a world where you can read a book without holding the physical object.

Read more:

Love, laughter, adventure and fantasy: a summer reading list for teens

I decided to introduce the option of a bibliomemoir – an increasingly popular form of creative non-fiction – into their final year assignment. This would allow me to tease out the particular connections students were making between literature and their own lives.

The idea for a bibliomemoir was sparked in a workshop run by our then writer-in-residence, celebrated Australian teen novelist and author of Puberty Blues, Dr Gabrielle Carey.

Carey described bibliomemoir as a piece of writing that shows literary criticism is “best written as a personal tale of the encounter between a reader and a writer”.

Written with flair and precision the students’ bibliomemoirs revealed the formative effects of reading on their lives. Many of their insights related directly to challenges of growing up in the digital age.

They wrote about responding to distraction and cultivating compassion, connection, concentration and resilience.

A bibliomemoir might be an account of how one book or author has shaped a person’s life. Or it might be the memoir of a life structured by reading books. In Outside of a Dog, for instance, Rick Gekoski tells his life story through 25 books that have influenced him, including authors from Dr Seuss to Sigmund Freud.

Gekoski pointed out in an interview that bibliomemoir reveals the formative effects of reading. I saw immediately that I could adapt bibliomemoir to help me understand how my students saw books as shaping their lives.

Read more:

5 Australian books that can help young people understand their place in the world

So, for the final essay of the introductory English course, Carey and I designed a new essay question. It invited students to write a brief bibliomemoir based on one of the novels in the course. Like a traditional essay this would allow me to evaluate their skills of written expression, argument and technical analysis of literary language.

Unlike a traditional essay, it would allow me to see inside their individual reading experience. I would be able to understand how these books were influencing my students’ view of the world and their understanding of themselves.

One student shared how reading Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway prompted a conversation with his flatmate about experiences of digital distraction and strategies for concentration:

Soon we came to the subject of Big Ben, which Woolf uses as a motif through the book. [My friend] said that the way Big Ben interrupted the characters’ thoughts reminded her of how a notification from your phone can interrupt your stream of thought.

I had also noticed the motif of Big Ben, however I appreciated it as an element of structure and pacing in a book that had no chapters, in fact I had sometimes structured my reading sessions around the ringing of Big Ben in the book.

Another student, reading of the mental torment experienced by the returned soldier Septimus in Mrs Dalloway, gained a new perspective on people who don’t seem to fit in. Reflecting on her initially judgemental perception of a dishevelled man boarding her bus the student asked: “was he so different from Septimus? Wise and lost?”.

She then explained she gained a new and unexpected perspective on life:

[Woolf] gave me glasses I never knew I needed – lenses smeared with multiple fingerprints that enhanced rather than hindered the view.

She concluded that

to be a reader is to suspend rigid views, to consider and honour the perspectives of the characters one meets.

A third student reflected on the challenges of reading itself, and on the rewards of persisting when structure and characterisation are unfamiliar. The student said she set out wanting to be an “inspired reader” but confessed to feeling “frustrated” by Woolf’s “merciless indifference” to her characters in Mrs Dalloway.

In noting this frustration, the student had registered the novel’s lack of clear protagonist or plotline. The novel is difficult to read because, while we do see individual characters trying to interpret their lives as coherent stories, Woolf refuses to impose an artificial grand narrative.

After sticking with it, however, the student recognised the novel’s achievement:

There lies the beauty of it: the ordinary day captured in time and words as a novel.

This student’s bibliomemoir was a story of the dividends paid by sustained concentration and a flexible mindset.

A fourth student used the bibliomemoir to analyse how Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey showed her the value of observing people closely, and has equipped her with resilience as a student facing the challenge of dyslexia:

I could not work out how to do the exact things my teachers wanted me to do. What I could do was learn to understand my teachers. By learning to watch them, like Austen watched people, and learning to understand them as people, I began to understand how to jump through their hoops.

While she couldn’t quantify the competencies reading books had given her, the student said she just knew books had formed who she was:

I cannot list the strategies that I employ when reading and writing […] I give all the credit to reading literature, to books like Northanger Abbey and writers like Jane Austen and so volunteer myself as an example of how reading literature is valuable in our era.

These examples revealed some of the many reasons new readers, even of the digital age, return to old books and old ways of reading them. The readers expressed an urgency for connection with narratives more complex than a news feed.

Read more:

If you can read this headline, you can read a novel. Here’s how to ignore your phone and just do it

They recognised that truthful self-reflection can be prompted by sustained engagement with fiction. They proved that connection with others, compassion and resilience are nurtured through a deepened understanding of story in the study of literature.

I can only conclude that for this group of readers, taking a book into their hands is a very deliberate act of identification with the bigger, shared story of reading.![]()

Kate Flaherty, Senior Lecturer (English and Drama) ANU, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at falling asleep while reading – certainly an issue for me.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/14/why-do-i-fall-asleep-when-i-read/

The link below is to an article that asks ‘why people aren’t reading books anymore?’ It also briefly comments on other survey findings, which seem largely irrelevant to the main question of the article.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/why-arent-people-reading-books-anymore

The link below is to an article that looks at how to raise a reader.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/13/how-to-raise-reader/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at reading aloud.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/02/12/participate-in-read-alouds/

You must be logged in to post a comment.