The link below is to an article that looks at historical fiction and the value of reading it.

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/authors/7-reasons-to-read-historical-fiction/

The link below is to an article that looks at historical fiction and the value of reading it.

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/authors/7-reasons-to-read-historical-fiction/

Elaine Reese, University of Otago

Humans are innately social creatures. But as we stay home to limit the spread of COVID-19, video calls only go so far to satisfy our need for connection.

The good news is the relationships we have with fictional characters from books, TV shows, movies, and video games – called parasocial relationships – serve many of the same functions as our friendships with real people, without the infection risks.

Read more:

Say what? How to improve virtual catch-ups, book groups and wine nights

Some of us already spend vast swathes of time with our heads in fictional worlds.

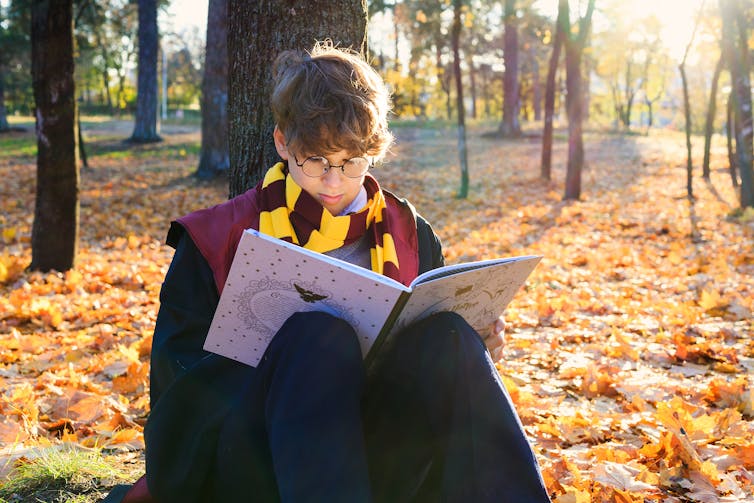

Psychologist and novelist Jennifer Lynn Barnes estimated that across the globe, people have collectively spent 235,000 years engaging with Harry Potter books and movies alone. And that was a conservative estimate, based on a reading speed of three hours per book and no rereading of books or rewatching of movies.

This human predilection for becoming attached to fictional characters is lifelong, or at least from the time toddlers begin to engage in pretend play. About half of all children create an imaginary friend (think comic strip Calvin’s tiger pal Hobbes).

Preschool children often form attachments to media characters and believe these parasocial friendships are reciprocal — asserting that the character (even an animated one) can hear what they say and know what they feel.

Older children and adults, of course, know that book and TV characters do not actually exist. But our knowledge of that reality doesn’t stop us from feeling these relationships are real, or that they could be reciprocal.

When we finish a beloved book or television series and continue to think about what the characters will do next, or what they could have done differently, we are having a parasocial interaction. Often, we entertain these thoughts and feelings to cope with the sadness — even grief — that we feel at the end of a book or series.

The still lively Game of Thrones discussion threads or social media reaction to the death of Patrick on Offspring a few years back show many people experience this.

Some people sustain these relationships by writing new adventures in the form of fan fiction for their favourite characters after a popular series has ended. Not surprisingly, Harry Potter is one of the most popular fanfic topics. And steamy blockbuster Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction for the Twilight series.

So, imaginary friendships are common even among adults. But are they good for us? Or are they a sign we’re losing our grip on reality?

The evidence so far shows these imaginary friendships are a sign of well-being, not dysfunction, and that they can be good for us in many of the same ways that real friendships are good for us. Young children with imaginary friends show more creativity in their storytelling, and higher levels of empathy compared to children without imaginary friends. Older children who create whole imaginary worlds (called paracosms) are more creative in dealing with social situations, and may be better problem-solvers when faced with a stressful event.

As adults, we can turn to parasocial relationships with fictional characters to feel less lonely and boost our mood when we’re feeling low.

As a bonus, reading fiction, watching high-quality television shows, and playing pro-social video games have all been shown to boost empathy and may decrease prejudice.

We need our fictional friends more than ever right now as we endure weeks in isolation. When we do venture outside for a walk or to go the supermarket and someone avoids us, it feels like social rejection, even though we know physical distancing is recommended. Engaging with familiar TV or book characters is one way to rejuvenate our sense of connection.

Plus, parasocial relationships are enjoyable and, as American literature professor Patricia Meyer Spacks noted in On Rereading, revisiting fictional friends might tell us more about ourselves than the book.

So cuddle up on the couch in your comfiest clothes and devote some time to your fictional friendships. Reread an old favourite – even one from your childhood. Revisiting a familiar fictional world creates a sense of nostalgia, which is another way to feel less lonely and bored.

Read more:

Couch culture – six months’ worth of expert picks for what to watch, read and listen to in isolation

Take turns reading the Harry Potter series aloud with your family or housemates, or watch a TV series together and bond over which characters you love the most. (I recommend Gilmore Girls for all mothers marooned with teenage daughters.)

Fostering fictional friendships together can strengthen real-life relationships. So as we stay home and save lives, we can be cementing the familial and parasocial relationships that will shape us – and our children – for life.![]()

Elaine Reese, Professor of Psychology, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Katherine Shwetz, University of Toronto

Masked people standing six feet apart. Empty shelves in the supermarket. No children in sight outside the school during recess.

The social upheaval caused by COVID-19 evokes many popular dystopian or post-apocalyptic books and movies. Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 crisis has sent many people rushing to fiction about contagious diseases. Books and movies about pandemics have spiked in popularity over the past few weeks: stuck at home self-isolating, many people are picking up novels such as Stephen King’s The Stand or streaming movies such as Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion.

Yet no one seems to fully agree on why reading books or watching movies about apocalyptic pandemics feels appealing during a real crisis with an actual contagious disease. Some readers claim that contagion fiction provides comfort, but others argue the opposite. Still more aren’t totally sure why they these narratives feel so compelling. Regardless, stories about pandemics call to them all the same.

So what, exactly, does pandemic fiction offer readers? My doctoral research on contagious disease in literature, a project that has required me to draw from both literary studies and health humanities, has taught me that a contagious disease is always both a medical and a narrative event.

Pandemics scare us partly because they transform other, less concrete, fears about globalization, cultural change, and community identity into tangible threats. Representations of contagious diseases allow authors and readers the opportunity to explore the non-medical dimensions of the fears associated with contagious disease.

Pandemic fiction does not offer readers a prophetic look into the future, regardless of what some may think. Instead, narratives about contagious disease hold up a mirror to our deepest, most inchoate fears about our present moment and explore different possible responses to those fears.

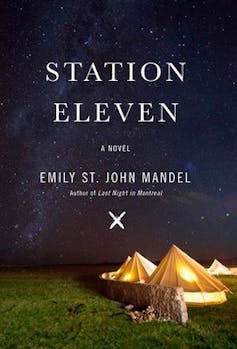

One novel that has grown in popularity over the past few weeks is been Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. Mandel’s novel follows a troupe of Shakespearean actors touring a post-apocalyptic landscape in a North America decimated by contagious disease.

Mandel’s novel serves as a test case for understanding the cultural response to COVID-19. The current pandemic sharpens fears about the relative instability of our communities (along with posing an immediate threat to our health, of course).

Coverage of Station Eleven claims that the text is uniquely relevant to the COVID-19 situation. This response treats Mandel’s novel as through it predicts what will happen as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Some news outlets even call the novel a “model for how we could respond” to an apocalyptic pandemic.

This is not the case. Station Eleven draws from apocalyptic literature, a narrative form that tells us more about the present than the future. Mandel herself has called Station Eleven more “a love letter to the world we find ourselves in” than a handbook for a post-apocalyptic future Indeed, Mandel herself publicly suggested that her novel is not ideal reading material for the present moment.

In fact, Station Eleven spends almost no time focused on the actual epidemic. The vast majority of the novel takes place before and after the outbreak. The medical details of the disease are less important than the rhetorical impact of the destructive virus.

Those fears in Station Eleven coalesce in scenes where communities must shift how they understand their relationship to one another. Characters stranded in an airport hangar, for example, must work together to build a new society that accommodates their shared traumatic experience. The pandemic in Mandel’s novel dramatically emphasizes to the characters not how to respond to a virus but, instead, how powerfully interconnected they truly are — the same thing COVID-19 is doing to us right now. Part of what pandemic fiction illuminates is how fears of invasion and the perceived threat of outsiders can diminish our humanity.

A virus crosses the boundary of your body, invading your very cells and changing your body on an incredibly intimate level.

It is unsurprising, then, that scholars see a strong relationship between contagious diseases and community identity. As anthropologist Priscilla Wald puts it, contagious disease “articulates community.” Pandemics emphasize how our individual bodies are connected to our collective body.

Left unchecked, the rhetorical implications of these narratives can lead to discriminatory behaviour or racism.

In Station Eleven, the villain — a cult leader prophet — continually denies his fundamental connection to those around him. He claims that he and his followers survived the epidemic because of their divine goodness and not because of luck. As a result, he engages in violent, abusive behaviours intended to quash the fear associated with interdependence — a common response to this fear.

The prophet in Station Eleven does not survive the novel; the surviving characters are the ones who accept that they cannot extricate themselves from connection to other people.

Contagious diseases — both in fiction and in real life — remind us that the social and cultural boundaries we use to structure society are fragile and porous, not stable and impermeable.

Although these works of literature cannot prophecize an imminent post-apocalyptic future, they can speak to our present.

So if reading a book about a pandemic appeals to you, go for it — but don’t use it as an instructional manual for an outbreak. Instead, that work of fiction can help you better understand and manage how the virus amplifies complex, diverse and multi-faceted fears about change in our communities and our world.![]()

Katherine Shwetz, PhD Candidate and Course Instructor, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

James Peacock, Keele University

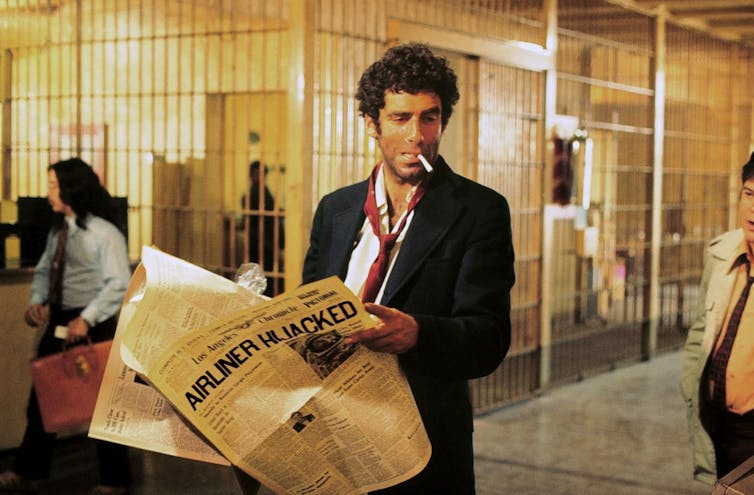

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that humans are connected, and that an individual’s actions can have profound consequences for the local community, the nation, and beyond. A good detective story, whether it takes place within an English country house or travels across international borders, reminds readers of this fundamental truth.

Detectives might be charming, eccentric amateurs like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, for example – or tough, world-weary professionals such as Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or Ian Rankin’s John Rebus.

But in both country-house and hard-boiled traditions their function is similar. They link disparate individuals and communities as they reconstruct events, and raise the possibility that, whoever pulled the trigger or administered the poison, we all share some responsibility for allowing such things to happen.

The selection below, I hope, reflects the genre’s diversity. What connects these books, for all their stylistic variety, is a preoccupation with links between people and communities and a desire to explore the implications of every action, deliberate or accidental.

The first full-length detective novel in American literature, The Dead Letter, published under the pen-name Seeley Register, is a curious hybrid. Featuring a country house that might be haunted, a clairvoyant child who – conveniently – is the detective’s daughter, and scenes of deathly pale women wandering moonlit gardens, mourning lost lovers, it shows how 19th-century detectives emerged from Gothic literature.

It is also a sentimental love story and a meditation on the corrupting power of money.

Like the Edgar Allan Poe stories which influenced it, and the Sherlock Holmes tales that followed, its narrator is not the detective, but the detective’s friend who – like the reader – is inclined to romanticise the sleuth’s heightened abilities.

The Dead Letter can be florid and outlandish, but it combines its eclectic elements to highly entertaining effect.

Philip Marlowe, the hero of seven novels and numerous short stories by Raymond Chandler, is tall, handsome, witty and admirably cynical about the effects of wealth. I’d love to recommend all the Marlowe stories and, given that its author intended it to be the last, The Long Goodbye might seem an idiosyncratic choice.

Stranger still, its pleasures are less to do with the detective thriller’s traditional virtues – intricate plotting, dynamic action – and more with the air of nostalgic melancholia Chandler conjures. There are murders, of course, and there is the vivid evocation of Los Angeles in its grubby splendour. There is also Marlowe’s trademark gift for metaphor: at the beginning, watching two people arguing outside a club, he remarks:

The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back.

But the novel’s heart is the unlikely friendship between Marlowe and Terry Lennox, a rich, dipsomaniac veteran locked in a loveless marriage, emotionally scarred by his combat experiences. As its title suggests, this epic and heartbreaking novel is about goodbyes: to innocence, to friendship, to the conventions of the detective story, and to an America untainted by consumerism.

Christie remains the pre-eminent writer of the “whodunit”. Her sheer prolificacy masks the fact that she is a consistently innovative plotter, unafraid to experiment with point-of-view in sometimes radical ways. She also produces stories that are dark, disturbing, and morally ambiguous – characteristics highlighted in recent adaptations such as the BBC’s version of The Pale Horse.

Though not among her most celebrated novels, Cat Among the Pigeons delightfully combines international espionage and country house mystery, with the “country house” being a prestigious girls’ prep school in England where members of staff start dying in suspicious circumstances.

Ingenious and laced with cruelty, it might be read as a story about Great Britain’s declining empire, or the fragile isolation of the upper classes, or it might simply be read as Mallory Towers with added murder.

This comprises three distinctive tales: City of Glass, Ghosts and The Locked Room, that conspire to connect in surprising ways. Often regarded as a model of “antidetection”, Auster’s trilogy frequently confounds expectations, promising stock elements of the hard-boiled story – the enigmatic loner gumshoe, the femme fatale, the dirty city – before jettisoning the cliches and exploring new territory.

Auster’s New York is a labyrinth ruled by chance, where one’s doppelganger can appear for no reason, where a man can devote his life to collecting and renaming bits of rubbish, and where “Paul Auster” can appear as a character. These are elaborate puzzles yet highly readable thrillers.

They are perfect stories for lockdown because they are about the consolations of reading and the paradoxical truth that the deeper into solitude we go, the more we understand our vital connection to others.

This is the first thriller starring Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins, an African-American factory worker in the Watts area of Los Angeles, who falls into detection when a stranger enters his local bar and offers him a missing persons job. Mosley’s work exemplifies the ways in which detective stories, tightly bound to specific places and times, function not only as entertainment but also as historical documents.

Devil in a Blue Dress, through energetic vernacular dialogue, realistic situations and wry observations on race relations, brilliantly evokes the lives of African-American families who moved from the southern states to California during the Second Great Migration.

More than the talented amateurs of the country house mystery, who possess a timeless quality and whose successful investigations tend to reinstate cosy normality – and Marlowe, a 20th-century knight errant with a nostalgic impulse – Easy Rawlins demonstrates that detectives are shaped by historical circumstances. He also happens to have one of the most captivatingly unstable sidekicks in all detective writing.

Detectives are people who move, tracing links between people, places and times. They are also expert readers: of clues, people, situations. During lockdown, these stories can transport us elsewhere and remind us that reading is an empathetic act, a way of reaching out and trying to connect with others.![]()

James Peacock, Senior Lecturer in English and American Literatures, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tennessee Witney via Shutterstock

Pam Lock, University of Bristol

The evolution of the novel and short story in the 19th century brought us one of the greatest human sources of comfort, besides food and a nice hot bath. When someone tells me they are planning to “curl up with a good book”, I am filled with a sense of peace on their behalf – of quiet enjoyment, perhaps accompanied by a little soft music and the crackle of a fire.

Regular solitary time is becoming the norm for many. Many of us are already tired of the enjoyable inanity of Netflix and Amazon Prime and are ready for something to lose ourselves in completely.

In the 19th century, the novel boomed as literacy and leisure time increased. Novels were frequently published in weekly parts, one to three chapters at a time. They had to be long enough to fill the required number of issues, and interesting enough to ensure readers kept buying the magazine or periodical (or run the risk of being cancelled mid-series). It is this combination that makes them a great resource for times like today.

Human beings are designed to love stories. Our brains seek narratives to help us make sense of the world. We communicate using stories to exchange knowledge and gain understanding. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote: “fiction is to the grown man what play is to the child” – through fiction we learn by imaginative experience.

Stories help us gain insight into things we cannot or should not experience. They also keep us safe – we tell each other cautionary tales all the time. So let’s do as our NHS doctors and nurses ask and learn from their stories of the virus – while also tucking ourselves away with some great old novels:

An exciting and funny adventure story about a man who goes on holiday and ends up as temporary king of Ruritania.

London-born adventurer Rudolf Rassendyll is persuaded to pretend to be the king after the real king is kidnapped by his evil half-brother on the eve of his coronation. A distant relation of the royal family, Rudolf is the king’s spitting image.

Beautifully written and filled with energy, the story romps across the beautiful scenery of Ruritania to the mysterious castle of Zenda. Rudolf is one of the most vibrant and positive characters I have come across and will fill you with hope. But what will he do when he falls in love with the king’s beautiful fianceé?

Read it for free on Project Gutenberg.

Cross-dressing, swashbuckling adventuress Leona Lacoste journeys from Rio de Janeiro to London to clear her father’s name.

Unknown to her until his death, he has been in hiding in their Brazilian home, having escaped some scandal or crime in England. To get to the bottom of the mystery, Leona must stop at nothing.

Disguised as a man to make the journey possible in the 1870s, she proves herself onboard a ship in a dramatic duel and seduces the daughter of a rich industrialist. But what will she uncover about her unknown family history?

Read it for free on Internet Archive, or buy from Victorian Secrets.

The celebrated mystery which launched a new type of story known as the sensation or enigma novel.

Walter Hartright is startled by the sudden appearance of a mysterious woman dressed in white walking on the road to London late at night. She asks him for directions and he decides to see her safely to a cab.

On the way, he discovers that she is from the very town to which he is about the journey to start work as an art teacher. Little does he know how this mysterious woman and the family in Limeridge will change his life forever.

Read it free on Project Gutenberg.

This may seem an unlikely choice but don’t let the TV and film adaptations fool you. This is a seriously good book. The adventurers who track and foil Count Dracula, led by Mina Harker and Abraham Van Helsing, are the epitome of organised and resourceful Victorian society.

This book is all about creating order from chaos: a reassuring ideal at the moment. Mina Harker’s way of life is doubly threatened by Dracula as he endangers both her fiancé, Jonathan Harker, whom he imprisons in his castle; and her best friend, Lucy Westenra, who is tormented by sleepwalking and mysterious illnesses.

Mina acts as the lynchpin for the five men who join together to defeat the count. The story that we are treated to is her collection of their accounts, creating a magnificent and lucid whole from diaries, cuttings, reports and letters. How will these rational beings thwart the supernatural power of the count?

Read it free on Project Gutenberg.

Jane Eyre fights for what she believes to be right. She stands up to those more powerful than herself, whether it be for her own rights or the good of others.

Orphaned and rejected by her guardian aunt, Jane trains to become a teacher at a charity school and then becomes governess to Adele, the ward of the wealthy and seemingly misanthropic Mr Rochester.

Slowly and unwillingly she falls in love with her master but he has a certain secret in his attic. What will this determined woman do to save herself from the temptations of his love?

Read it free on Project Gutenberg:.

You’ll have noticed that I have stuck to books with happy endings, or at least tidy ones. There is no Thomas Hardy (you must take broadcaster Andy Hamilton’s advice and read Hardy’s novels backwards to get a happy ending), and no George Eliot, whose wonderfully complex characters are very real and intriguing but not often comforting.

Some are old, familiar favourites, others lesser known but equally enjoyable. The list is by no means complete. It is intended to be the beginning of a journey back to familiar friends and an exploration of new ones. They are shared with love and care in the hope they will make you feel a little better for their company.![]()

Pam Lock, Lecturer, English Literature (Specialist in Victorian Literature and Alcohol), University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock

Jodi McAlister, Deakin University

Romance fiction has two defining features.

First, it centres on a love story. Secondly, it always ends well.

Our protagonists end up together (if not forever, then at least for the foreseeable future) and this makes the world around them a little bit better, too.

In times of uncertainty, upheaval and chaos, readers often turn to romance fiction: during the second world war, Mills & Boon was able to maintain its paper ration by arguing its books were good for the morale of working women.

The books the company was producing in this period were not about the war. Most never even mentioned it. Instead, they provided an escape for readers to a world where they could be assured everything was going to turn out all right: love would conquer all, villains would be defeated, and lovers would always find their way back to each other.

Read more:

How to learn about love from Mills & Boon novels

Today, romance publishing is a billion-dollar industry, with thousands of novels published each year. It covers a wide range of subgenres: from historical to contemporary, paranormal to sci-fi, from novels where the only physical interaction between the protagonists is a kiss, to erotic romance where sex is fundamental to the story.

Rule 34 of the internet states if you can think of something, then there’s porn of it. The same, I would argue, is true for romance fiction.

But where to begin? As both a scholar of romance fiction and an avid reader of it, I’ve put together this list of five great reads for people who might want to start exploring the genre.

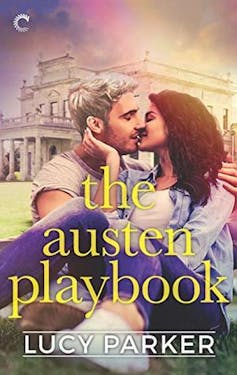

The Austen Playbook by Lucy Parker

The Austen Playbook is the fourth book in Parker’s London Celebrities series (all only loosely connected, so you can jump in anywhere).

Heroine Freddy is an actress from an esteemed West End family, trying to balance her desire to perform in musicals and crowd-pleasers over her family pushing her towards serious drama. Hero Griff is a theatre critic and his family estate is playing host to a wacky live-action Jane Austen murder mystery, in which Freddy is playing Lydia.

Parker is a gifted author, and this book is a light, bright and sparkling delight.

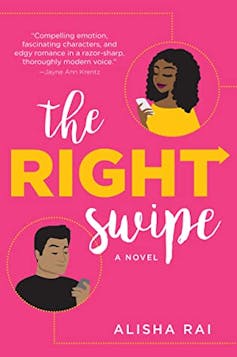

The Right Swipe by Alisha Rai

Many people now find partners on dating apps, but these apps are often not exactly friendly for women.

Rai addresses that to great effect in The Right Swipe, where heroine Rhiannon is the designer of a dating app designed specifically for women.

She meets hero Samson the first time as a result of swiping right, and then the second time, months later, when he’s teamed up with one of her primary business rivals…

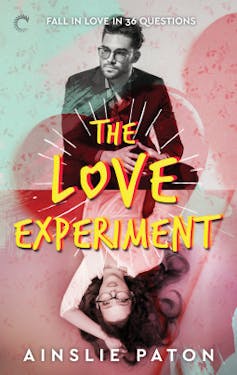

The Love Experiment by Ainslie Paton

Paton is one of Australia’s smartest and most underrated romance authors. The Love Experiment draws on the 36 questions developed by psychologist Arthur Aron to explore whether intimacy could be generated or intensified between two people if they exchanged increasingly personal information.

The 36 questions were popularised in Mandy Len Catron’s 2015 New York Times essay To Fall In Love With Anyone, Do This. Here, journalist protagonists Derelie and Jackson undertake the experiment in Paton’s book, only to find love is more complex than 36 questions.

Project Saving Noah by Six de los Reyes

This book emerges from RomanceClass, a fascinating community of English-language romance writers and readers based in the Philippines. One of their distinctive features is their collaboration with local actors in Manila to perform excerpts from the books (including Project Saving Noah) at their regular gatherings. I was privileged enough to attend one of these last year.

Protagonists Noah and Lise are graduate students in oceanography competing for one spot on a research project, while simultaneously being forced to work together. Their romance is conflicted and compelling, but what stands out about this book is the vividness with which their environment – natural and academic – is constructed.

Mrs Martin’s Incomparable Adventure by Courtney Milan

If Milan’s name sounds familiar, it’s because she was at the centre of the recent scandal engulfing the Romance Writers of America, which penetrated through romance’s usual cultural invisibility.

When she’s not standing up against systemic racism, Milan writes excellent, mostly historical, romance. Mrs Martin is a delightful historical romp, as our two heroines Bertrice (aged 73) and Violetta (aged 69) team up against Violetta’s terrible nephew, and fall in love and eat cheese on toast together.![]()

Jodi McAlister, Lecturer in Writing, Literature and Culture, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Liu zishan via Shutterstock

Gavin Miller, University of Glasgow

Science fiction has struggled to achieve the same credibility as highbrow literature. In 2019, the celebrated author Ian McEwan dismissed science fiction as the stuff of “anti-gravity boots” rather than “human dilemmas”. According to McEwan, his own book about intelligent robots, Machines Like Me, provided the latter by examining the ethics of artificial life – as if this were not a staple of science fiction from Isaac Asimov’s robot stories of the 1940s and 1950s to TV series such as Humans (2015-2018).

Psychology has often supported this dismissal of the genre. The most recent psychological accusation against science fiction is the “great fantasy migration hypothesis”. This supposes that the real world of unemployment and debt is too disappointing for a generation of entitled narcissists. They consequently migrate to a land of make-believe where they can live out their grandiose fantasies.

The authors of a 2015 study stress that, while they have found evidence to confirm this hypothesis, such psychological profiling of “geeks” is not intended to be stigmatising. Fantasy migration is “adaptive” – dressing up as Princess Leia or Darth Vader makes science fiction fans happy and keeps them out of trouble.

But, while psychology may not exactly diagnose fans as mentally ill, the insinuation remains – science fiction evades, rather than confronts, disappointment with the real world.

The psychological accusation that science fiction evades real life goes back to the 1950s. In 1954, the psychoanalyst Robert Lindner published his case study of the pseudonymous “Kirk Allen”, a patient who maintained an extraordinary fantasy life modelled on pulp science fiction.

Allen believed he was at once a scientist on Earth – and simultaneously an interplanetary emperor. He believed he could enter his other life by mental time travel into the far-off future, where his destiny awaited in scenes of power, respect, and conquest – both military and sexual.

Lindner explained Allen’s condition as an escape from overwhelming mental anguish rooted in childhood trauma. But Lindner, himself a science fiction fan, remarked also on the seductive attraction of Allen’s second life, which began to offer, as he put it, a “fatal fascination”. The message was clear. Allen’s psychosis was extreme, but it showed in stark clarity what drew readers to science fiction: an imagined life of power and status that compensated for the readers’ own deficiencies and disappointments.

Lindner’s words mattered. He was an influential cultural commentator, who wrote for US magazines such as Time and Harper’s. The story of Kirk Allen was published in the latter, and in Lindner’s book of case studies, The Fifty-Minute Hour, which became a successful popular paperback.

Psychology had very publicly diagnosed science fiction as a literature of evasion – an “escape hatch” for the mentally troubled. Science fiction answered back, decisively changing the genre in the following decades.

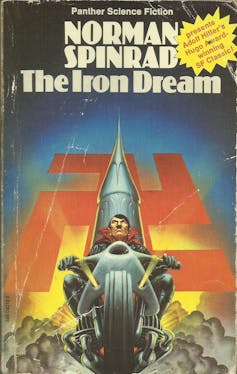

To take one example: Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream (1972) purports to reprint a prize-winning 1954 science fiction novel. The novel is apparently written, in an alternate history timeline, by Adolf Hitler, who gave up politics, emigrated to the US, and became a successful science fiction author and illustrator. A fictional critical afterword explains that Hitler’s novel, with its “fetishistic military displays and orgiastic bouts of unreal violence”, is just a more extreme version of the “pathological literature” that dominates the genre.

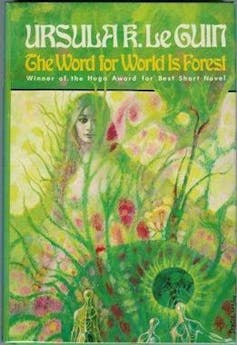

In her review of The Iron Dream, the now-celebrated science fiction author Ursula Le Guin – daughter of the distinguished anthropologist Alfred Kroeber – wrote that the “essential gesture of SF” is “distancing, the pulling back from ‘reality’ in order to see it better”, including “our desires to lead, or to be led”, and “our righteous wars”. Le Guin wanted science fiction to make strange the North American society of her time, showing afresh its peculiar psychology, culture, and politics.

In 1972, the US was still fighting the Vietnam War. In the same year, Le Guin offered her own “distanced” version of social reality in The Word for World is Forest, which depicts the attempted colonisation of an inhabited alien planet by a macho, militaristic Earth society intent on conquering and violating the natural world – a semi-allegory for what the USA was doing at the time in south-east Asia.

As well as repudiating the worst parts of the genre, such responses implied a positive model for science fiction. Science fiction wasn’t about evading reality – it was a literary anthropology which made our own society into a foreign culture which we could stand back from, reflect on, and change.

Rather than ask us to pull on our anti-gravity boots, open the escape hatch and leap into fantasy, science fiction typically aspires to be a literature that faces up to social reality. It owes this ambition, in part, to psychology’s repeated accusation that the genre markets escapism to the marginalised and disaffected.![]()

Gavin Miller, Senior Lecturer in Medical Humanities, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Motortion Films via Shutterstock

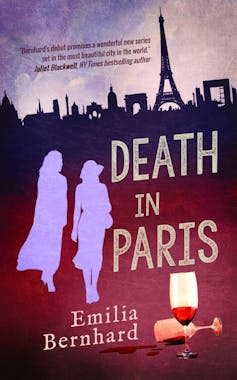

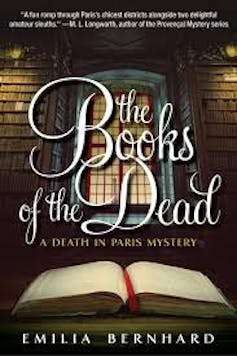

Emily Bernhard Jackson, University of Exeter

Mystery is the bestselling genre in literature. Crime/mystery fiction, to give the genre its full title, beats inspirational, science fiction, horror and apparently even romance to take the top spot.

And why not? There’s someone for everyone in crime/mystery – elderly lady sleuths, amateur Palestinian sleuths, professional Belgian sleuths, thoughtful Scottish police officers, embittered Scottish police officers, damaged Irish police officers, weary Scandinavian police officers, former army officer detectives, amateur girl detectives, sad drunk amateur girl detectives. There’s even a detective who partners up with a skeleton.

What there doesn’t seem to be much of in mystery fiction, however, is female detectives who begin detecting in middle age (two cases in point: Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski was 32 when we began to follow her adventures, while Patricia Cornwell’s Kay Scarpetta was 36). Women in the 40-to-60 range don’t get much of a showing as main characters in literature generally, so maybe it’s no surprise that they don’t show up as headliners in the mystery genre.

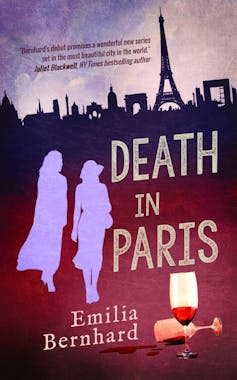

But it’s a surprise if you’re a woman in your 40s who is beginning to write mystery novels – which not so long ago I was. And while it’s a cliche that people write what they know, when I decided to write a mystery I entered into that cliche wholeheartedly. I started writing mysteries in my 40s – and I made my detectives two women in their 40s.

But while I designed my detectives in part to mirror myself, I also chose their age for entirely different reasons. For all its advances and improvements, contemporary culture remains uncomfortable, not just with middle-aged women, but to an even greater degree with contentedly single middle-aged women – and to an even greater degree than that with childless women who are childless by choice. I wanted to confront this odd aversion head on, so I made sure that between them my detectives fill all these categories.

This decision is a small one, but for me it engaged with a question I’ve long struggled with, the question of what, intellectually, literature is supposed to do. Should it report on the world as it is, or should it model the world as it might – could, should, would – be?

Recent fiction may not have been filled with middle-aged women, but it has been filled with angry ones. It’s jam packed with dystopian models of female repression and with women and men implacably set against one other: look at Naomi Alderman’s The Power, Leni Zumas’s Red Clocks, Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments. As I began to create my fictional world, I was troubled by the question of whether these outpourings of rage, all justified, all earned, are enough.

Read more:

Review: The Testaments – Margaret Atwood’s sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale

In one way this literature is unquestionably good: female rage is something else culture has assiduously avoided considering for centuries, and during those centuries women have been subjugated, silenced, used and abused in ways that deserve outpourings of anger.

Nor is this landscape of female repression changing quickly, and there is value in forcing it before readers’ eyes. In a recent article for The Guardian about the Staunch Prize, the new award for the best crime/mystery novel that does not feature violence against women, the novelist Kaite Welsh wrote that she wouldn’t “sanitise my writing in service of some fictional, feminist utopia … my work lies in marrying my imagination with the ugly truth”. This is an important argument.

But while I don’t care about the absence of feminist utopias, I do care about the absence of writing that models the future we want. What will it be like, the world we’re striving for where the playing field is level and men and women are just people being people together? I believe that we can only imagine based on what we’ve seen, and that it’s part of literature’s job to help us see what doesn’t yet exist but could.

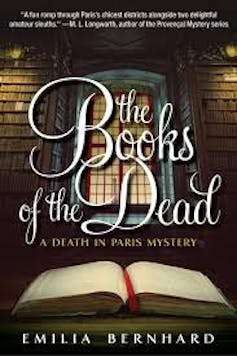

For this reason, although I grounded my novels firmly in the present (well, Death in Paris is set in 2014 and The Books of the Dead in 2016), I made some specific choices about that present. In my books, every person in a powerful position is a woman. Department heads and doctors, sources of knowledge and implacable foes: all are female.

More importantly, as far as I was concerned, no one draws attention to that. It’s so normal as to be unworthy of note. Nor does anyone comment on the fact that both my detectives are childless, and one remains happily unmarried in her mid-40s. Both of these detectives are heterosexual, but I made that decision so I could give each a husband or boyfriend who sees them as an intellectual and emotional equal, and for whom that equality is also the norm. The women in my books have and enjoy good sex, and they have and enjoy good conversations – almost none of them about men.

My books are full of oversights and omissions, and I’m far from satisfied with them. But what I aimed to do, and am still trying to do, is to augment the justifiable depictions of anger, the honest depictions of ongoing brutality and violence against women, with a small model that allows for a morsel of hope.![]()

Emily Bernhard Jackson, Lecturer in English, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Andre Spicer, City, University of London

The future isn’t what it used to be, at least according to the Canadian science fiction novelist William Gibson. In a interview with the BBC, Gibson said people seemed to be losing interest in the future. “All through the 20th century we constantly saw the 21st century invoked,” he said. “How often do you hear anyone invoke the 22nd century? Even saying it is unfamiliar to us. We’ve come to not have a future”.

Gibson thinks that during his lifetime the future “has been a cult, if not a religion”. His whole generation was seized by “postalgia”. This is a tendency to dwell on romantic, idealised visions of the future. Rather than imagining the past as an ideal time (as nostalgics do), postalgics think the future will be perfect. For example, a study of young consultants found many suffered from postalgia. They imagined their life would be perfect once they were promoted to partner.

“The Future, capital-F, be it crystalline city on the hill or radioactive post-nuclear wasteland, is gone”, Gibson said in 2012. “Ahead of us, there is merely … more stuff … events”. The upshot is a peculiarly postmodern malaise. Gibson calls it “future fatigue”. This is a condition where we have grown weary of an obsession with romantic and dystopian visions of the future. Instead, our focus is on now.

Gibson’s diagnosis is supported by international attitude surveys. One found that most Americans rarely think about the future and only a few think about the distant future. When they are forced to think about it, they don’t like what they see. Another poll by the Pew Research Centre found that 44% of Americans were pessimistic about what lies ahead.

But pessimism about the future isn’t just limited to the US. One international poll of over 400,000 people from 26 countries found that people in developed countries tended to think that the lives of today’s children will be worse than their own. And a 2015 international survey by YouGov found that people in developed countries were particularly pessimistic. For instance, only 4% of people in Britain thought things were improving. This contrasted with 41% of Chinese people who thought things were getting better.

So why has the world seemingly given up on the future? One explanation might be that deep pessimism is the only rational response to the catastrophic consequences of global warming, declining life expectancy and an increasing number of poorly understood existential risks.

But other research suggests that this widespread pessimism as irrational. People who support this view, point out that on many measures the world is actually improving. And an Ipsos poll found that people who are more informed tend to be less pessimistic about the future.

Read more:

The end of the world: a history of how a silent cosmos led humans to fear the worst

Although there may be some objective reasons to be pessimistic, it is likely that other factors may explain future fatigue. Researchers who have studied forecasting say there are good reasons why we might avoid making predictions about the distant future.

For one, forecasting is always a highly uncertain activity. The longer the time frame one is making predictions about and the more complicated the prediction, the more room there is for error. This means that while it might be rational to make a projection about something simple in the near future, it is probably pointless to make projections about something complex in the very distant future.

Economists have known for many years that people tend to discount the future. That means we put a greater value on something which we can get immediately than something we have to wait for. More attention is paid to pressing short-term needs while longer-term investments go unheeded.

Psychologists have also found that futures that are close at hand seem concrete and detailed while those that are further away seem abstract and stylised. Near futures were more likely to be based on personal experience, while the distance future was shaped by ideologies and theories.

When a future seems to be closer and more concrete, people tend to think it is more likely to occur. And studies have shown that near and concrete futures are also more likely to spark us into action. So the preference for concrete, close-at-hand futures mean people tend to put off thinking about more abstract and distant possibilities.

The human aversion to thinking about the future is partially hardwired. But there are also particular social conditions that make us more likely to give up on the future. Sociologists have argued that for people living in fairly stable societies, it is possible to generate stories about what the future might be like. But in moments of profound social dislocation and upheaval, these stories stop making sense and we lose a sense of the future and how to prepare for it.

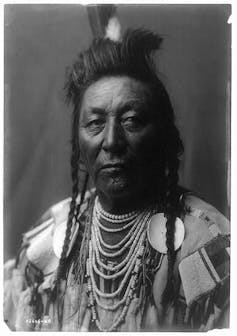

This is what happened in many native American communities during colonialism. This is how Plenty Coups, the leader of the Crow people, described it: “When the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened.”

But instead of being thrown into a sense of despair by the future, Gibson thinks we should be a little more optimistic. “This new found state of No Future is, in my opinion, a very good thing … It indicates a kind of maturity, an understanding that every future is someone else’s past, every present is someone else’s future”.![]()

Andre Spicer, Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Motortion Films via Shutterstock

Emily Bernhard Jackson, University of Exeter

Mystery is the bestselling genre in literature. Crime/mystery fiction, to give the genre its full title, beats inspirational, science fiction, horror and apparently even romance to take the top spot.

And why not? There’s someone for everyone in crime/mystery – elderly lady sleuths, amateur Palestinian sleuths, professional Belgian sleuths, thoughtful Scottish police officers, embittered Scottish police officers, damaged Irish police officers, weary Scandinavian police officers, former army officer detectives, amateur girl detectives, sad drunk amateur girl detectives. There’s even a detective who partners up with a skeleton.

What there doesn’t seem to be much of in mystery fiction, however, is female detectives who begin detecting in middle age (two cases in point: Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski was 32 when we began to follow her adventures, while Patricia Cornwell’s Kay Scarpetta was 36). Women in the 40-to-60 range don’t get much of a showing as main characters in literature generally, so maybe it’s no surprise that they don’t show up as headliners in the mystery genre.

But it’s a surprise if you’re a woman in your 40s who is beginning to write mystery novels – which not so long ago I was. And while it’s a cliche that people write what they know, when I decided to write a mystery I entered into that cliche wholeheartedly. I started writing mysteries in my 40s – and I made my detectives two women in their 40s.

But while I designed my detectives in part to mirror myself, I also chose their age for entirely different reasons. For all its advances and improvements, contemporary culture remains uncomfortable, not just with middle-aged women, but to an even greater degree with contentedly single middle-aged women – and to an even greater degree than that with childless women who are childless by choice. I wanted to confront this odd aversion head on, so I made sure that between them my detectives fill all these categories.

This decision is a small one, but for me it engaged with a question I’ve long struggled with, the question of what, intellectually, literature is supposed to do. Should it report on the world as it is, or should it model the world as it might – could, should, would – be?

Recent fiction may not have been filled with middle-aged women, but it has been filled with angry ones. It’s jam packed with dystopian models of female repression and with women and men implacably set against one other: look at Naomi Alderman’s The Power, Leni Zumas’s Red Clocks, Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments. As I began to create my fictional world, I was troubled by the question of whether these outpourings of rage, all justified, all earned, are enough.

Read more:

Review: The Testaments – Margaret Atwood’s sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale

In one way this literature is unquestionably good: female rage is something else culture has assiduously avoided considering for centuries, and during those centuries women have been subjugated, silenced, used and abused in ways that deserve outpourings of anger.

Nor is this landscape of female repression changing quickly, and there is value in forcing it before readers’ eyes. In a recent article for The Guardian about the Staunch Prize, the new award for the best crime/mystery novel that does not feature violence against women, the novelist Kaite Welsh wrote that she wouldn’t “sanitise my writing in service of some fictional, feminist utopia … my work lies in marrying my imagination with the ugly truth”. This is an important argument.

But while I don’t care about the absence of feminist utopias, I do care about the absence of writing that models the future we want. What will it be like, the world we’re striving for where the playing field is level and men and women are just people being people together? I believe that we can only imagine based on what we’ve seen, and that it’s part of literature’s job to help us see what doesn’t yet exist but could.

For this reason, although I grounded my novels firmly in the present (well, Death in Paris is set in 2014 and The Books of the Dead in 2016), I made some specific choices about that present. In my books, every person in a powerful position is a woman. Department heads and doctors, sources of knowledge and implacable foes: all are female.

More importantly, as far as I was concerned, no one draws attention to that. It’s so normal as to be unworthy of note. Nor does anyone comment on the fact that both my detectives are childless, and one remains happily unmarried in her mid-40s. Both of these detectives are heterosexual, but I made that decision so I could give each a husband or boyfriend who sees them as an intellectual and emotional equal, and for whom that equality is also the norm. The women in my books have and enjoy good sex, and they have and enjoy good conversations – almost none of them about men.

My books are full of oversights and omissions, and I’m far from satisfied with them. But what I aimed to do, and am still trying to do, is to augment the justifiable depictions of anger, the honest depictions of ongoing brutality and violence against women, with a small model that allows for a morsel of hope.![]()

Emily Bernhard Jackson, Lecturer in English, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.