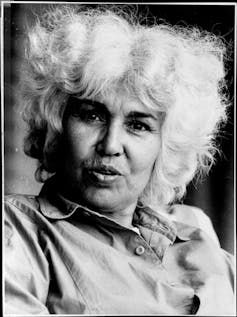

In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images

Amal Amireh, George Mason University

Egypt’s Nawal El Saadawi was the foremost Arab feminist thinker of the past 50 years. Her ideas inspired generations of Arab women, but also provoked controversy and criticism.

She was prolific, publishing over 50 books of fiction and non fiction in Arabic, many translated and receiving global attention.

Focusing on sex, politics, and religion, El Saadawi believed that patriarchy, capitalism and imperialism are intertwined systems that oppress Arab women and prevent them from reaching their full potential.

The trajectory of El Saadawi’s intellectual life follows major developments in Arab society and culture from the 1940s to the present. To understand her contribution, it’s important to see her in the context of the historical moment that made her work possible, necessary and provocative.

Born into change

Born in 1931 in the village of Kafr Tahla near Cairo, into a middle class family, El Saadawi was the second of nine children. She came of age at the cusp of key changes such as the drive for girls’ education pioneered by an earlier generation of activists. She, in fact, attended a school established by Nabawyya Mousa, an activist for women’s education.

Supported by a father who believed in the importance of education for social mobility, El Saadawi attended the British School. Her academic excellence allowed her to evade early marriage and receive a scholarship to study medicine at the University of Cairo. She graduated in 1955 with a specialisation in psychiatry.

Read more:

Nawal El Saadawi: Egypt’s grand novelist, physician and global activist

At university she was exposed to nationalist, anti-colonialist politics. She participated in student demonstrations against the British and married a fellow activist. They had a daughter but divorced. Her second marriage ended in divorce after her husband stipulated she stops writing. Her third marriage, to Sherif Hetata a novelist and former political prisoner, lasted over 40 years but also ended in divorce. They had a son.

After medical school, El Saadawi returned to her village. Working as a countryside physician exposed her to class and gender inequities that further shaped her thinking. She witnessed first hand the harmful consequences of entrenched patriarchal practices such as female genital cutting and defloration inflicted on the bodies of poor village women, detailing some of her experiences in Memoirs of a Woman Doctor (1958).

Travels around the world

In 1963, she was appointed director general for public health education and was able to travel to international forums and conferences. These travels, documented in My Travels Around the World (1991), gave her perspective on the struggles of other women. She always asserted that patriarchy is a universal system of oppression, not only restricted to Arab or Muslim societies.

Thus while she did not hesitate to call female genital cutting “barbaric” she also resisted its sensationalisation in the West as a mark of difference between first world and third world women. She insisted that all women are circumcised if not physically then “psychologically and educationally”. She rejected the idea that western women are needed to help liberate their Arab or African sisters.

But it was the 1967 Six-Day War that pushed El Saadawi to a more radical public position regarding gender. This crushing Arab military defeat by Israel created a crisis for Arab intellectuals generally, compelling them to take a surgical look at their societies.

Feminist manifestos

El Saadawi believed that patriarchy and gender inequalities are root causes for Arab defeatism. She rose to fame in the 1970s with a series of feminist manifestos that put her on the map. Women and Sex (1971) was the first. In it, she condemned the violence committed against women’s bodies including virginity tests, honour killings, wedding night defloration and genital cutting.

Anthony Lewis/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

She exposed her society’s ignorance and double standards regarding women’s bodies and sexuality. Her first chapter, for instance, was focused on the clitoris and its importance for women’s sexual pleasure. She argued that exploitative marriages are no different from prostitution.

Using her medical knowledge, she argued that differences between the sexes are not natural but socially constructed by patriarchal practices – and can therefore be changed through legislation and education. However, she insisted that gender justice will not be possible under a capitalist society. Soon after publication, she lost her job and the magazine she had founded was closed down.

But the positive reception of her work among the public encouraged her to write other polemics including The Female is the Origin (1974), Woman and Psychological Struggle (1976), Man and Sex (1976) and The Hidden Face of Eve (1977). Combining anecdotes of patients, her biography, medical and social research and polemic against gender injustice, she spoke with the authority of a physician, the knowledge of an intellectual and the passion of an injured woman.

The power of fiction

El Saadawi viewed herself first and foremost as a novelist, using fiction to express many of her ideas regarding sex and society. Her first novel to attract attention, for example, was Woman at Point Zero (1983). Her main character, working class Firdaus, experiences sexual exploitation and assault and eventually is executed by the state for killing her pimp.

While she made significant contributions to the Arab feminist novel, El Saadawi’s fiction was received less enthusiastically than her other work, criticised for being repetitive and her female characters dismissed as one-dimensional.

Religious backlash

But the creativity of fiction allowed a space to critique another taboo in Arab society – religion. Her later works were written in response to a religious backlash that had taken over public life in Egypt and beyond.

In The Fall of the Imam (1987), for instance, she condemns the patriarchal regime of President Anwar el-Sadat for using the authority of religion to shore up political legitimacy and marginalise dissidents. The novel was banned by Al Azhar, Egypt’s highest religious authority. In it and God Dies by the Nile (1985), the El Saadawian heroine kills the male authority figures who use religion to oppress them.

In The Innocence of the Devil (1994), El Saadawi goes further: she makes God and the Devil characters in a mental asylum and directly indicts both Islam and Christianity as oppressive of women. Her critique of religion made her an easy target for fundamentalists in Egypt. Her hostility to political Islam was rooted in the personal experience of censorship and death threats.

Her critiques also alienated two other kinds of readers: self-identified Muslims and liberal western academics. As religion was playing a more prominent role in public life in Egypt, many found her views too radical.

For her dissent, she paid a price. In 1981 she was thrown in jail by the Sadat regime along with a thousand other intellectuals. There she wrote Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1986) using an eye pencil smuggled to her by a sex worker on toilet paper given to her by a murderer.

After her release, she formed The Arab Woman Solidarity Association. It was closed down by Hosni Mubarak’s government in 1991. Unwaivering, she ran against Mubarak in the 2004 presidential elections. During the 2011 uprising that deposed Mubarak, El Saadawi, in her 80s, held seminars in tents in Tahrir Square to radicalise a new generation.

This article is based on Amireh’s chapter in the book Fifty-One Key Feminist Thinkers (Routledge).![]()

Amal Amireh, Associate professor, George Mason University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.