The link below is to an article reporting on the 2020 Singapore Book Awards winners.

For more visit:

https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/08/singapore-book-awards-2020-a-dessert-guide-wins-book-of-the-year-covid19/

The link below is to an article reporting on the 2020 Singapore Book Awards winners.

For more visit:

https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/08/singapore-book-awards-2020-a-dessert-guide-wins-book-of-the-year-covid19/

The link below is to a book review of ‘Caste – The Origins of Our Discontents,’ by Isabel Wilkerson

For more visit:

https://time.com/5870485/isabel-wilkerson-caste/

Malachi McIntosh, Queen Mary University of London

In many ways, the current state of the world seems unprecedented. The last few years – but especially 2020 – have brought shocks that no one could have foreseen.

Although much headline news has been cause for anxiety, there have been a few notable moments of hope. For me, like so many, the worldwide protests in response to the murder of George Floyd have been among them. In the centre of the uprising’s hopeful surprises has been the way they’ve torn open space for conversations about race and racism in the UK.

Why don’t we teach all British schoolchildren about colonialism? Why does it take so much more convincing to have the statues of slaveowners removed than those of others responsible for past atrocities? Why were so many young people of colour so quickly mobilised to say “the UK is not innocent”, in solidarity with their peers on the streets in the United States?

With the boom in interest in the histories of colonialism, empire and the British civil rights movement in response to Black Lives Matter protests, has come an aligned boom in interest in Black British writing.

Candice Carty-Williams and Bernardine Evaristo won significant firsts for Black authors at the British Book awards – book of the year and author of the year, respectively. Reni Eddo-Lodge, author of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race, became the first Black Briton to top the paperback non-fiction chart, while Evaristo topped the fiction list.

Across social media and newspapers, reading lists proliferated, apparently responding to a hunger from readers of all backgrounds to gain knowledge of issues and the history of race and racism they’d never received in schools or universities.

For many in and on the fringes of the publishing industry, it’s felt hopeful that a moment of real recognition for Black British writing, in an echo of the attention being paid to Black British lives, has arrived.

But has it really? Although the accelerated pace of interest feels unique, the pattern – social unrest triggering readerly interest in the works of writers of colour – is, unfortunately, not.

Immediately after the second world war there was a similar boom. Britain was about to enter a long phase of decolonisation, and its demographic make-up, through waves of colonial then ex-colonial migration, was on course to permanently change. This opened up space and piqued curiosity for works from the most visible group at the centre of social transformation – at that time Caribbean emigrants.

As detailed in Kenneth Ramchand’s book The West Indian Novel and Its Background, from 1950 to 1964, over 80 novels by Caribbean authors, including classics like In the Castle of My Skin by by George Lamming and A House for Mr Biswas by VS Naipaul were published in London – far more than those published in the Caribbean itself.

What’s most significant about that spike is that it didn’t last. As Caribbean migration waned after the passage of a series of restrictive immigration acts from 1962 to 1971, so did the opportunities for writers from Caribbean backgrounds.

This was evident in the fortunes of most of the those published in Britain post-war. The likes of Edgar Mittelholzer and John Hearne – then known and widely published – and even Samuel Selvon – now widely known and respected – found their works falling out of print.

Attention then shifted to Black writers from the African continent – primarily those from west Africa, like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka – where the progress of decolonisation was taking dramatic turns. But this interest also waned.

There have been more recent booms, for example in the 1980s after the New Cross fire in 1981, which sparked protests in south London after 13 young black people were killed, and the Brixton uprising of the same year in response to excessive and, at times, violent policing in the area.

Then, around the turn of the millennium, rechristened “multicultural” writing rose, alongside visible demographic change, through the successes of Zadie Smith, Andrea Levy, Monica Ali and others. These were breakthroughs significant enough for Wasafiri, the magazine where I work and which has been championing Black British and British Asian writing since 1984, to declare in 2008 that Black Britons had “taken the cake” of British letters.

Yet in 2016, eight years later, only one debut novel from a Black British male author, Robyn Travis, was published in the UK.

In her memoirs, the British writer and editor Diana Athill calls the post-war boom in writing from then-colonies a result of short-lived “liberal guilt” combined with curiosity about the peoples and nations disconnecting from Britain. There are concerning signs along these lines in our present.

In their recent report – a result of over a hundred interviews with those in the field – Anamik Saha and Sandra van Lente reveal that British publishers feel both that they ought to publish more writers of colour and that those same writers belong to a particular niche with limited quality and limited appeal to their target readers.

Anticipating this conversation in her 2019 essay What a Time to Be a (Black) (British) (Womxn) Writer, first published in the book Brave New Words on the eve of her Booker Prize win, Bernardine Evaristo both celebrated and questioned the growing body of Black British writing.

Something, she notes in the essay, is definitely shifting, but she wonders how far it will really shift – if Black Britons are being published in greater numbers but on singularly narrow terms. Like their forebears in the 1950s, 1960s, 1980s and early 2000s, are there only certain stories Black writers are allowed to tell? Only certain messages they’re expected to convey?

While it is far too early to make a judgement on how long the current boom will last, the way this moment repeats a pattern of social change followed by publishing frenzy is at least worthy of attention – and perhaps scepticism. So often the present seems unprecedented, but in order for it to be truly revolutionary, novel, status-quo shifting – liberating – the changes we see within it have to be sustained.![]()

Malachi McIntosh, Emeritus lecturer in British Black and Asian Literature, Queen Mary University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

DPPA/AAP

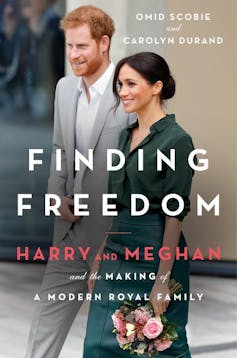

Giselle Bastin, Flinders University

A new book about the Duke and Duchess of Sussex is generating sensational headlines about their private life, defiance of Queen Elizabeth and how Prince William “behaved like a snob” to his future sister-in-law.

It is also the latest foray of British royals into the minefield that is royal

biography.

Finding Freedom: Harry and Meghan and the Making of a Modern Royal Family, by royal reporters Omid Scobie and Carolyn Durand, promises stories about how the royal couple has struggled with “the many rumours and misconceptions that [have] plagued” them since their 2017 engagement.

According to numerous reports, this also includes tales of their clashes with palace officials and members of their own families, as well as their courtship and ill-treatment by the British press.

A spokesperson for the couple has firmly said they “did not contribute to ‘Finding Freedom’”. But there is widespread speculation Harry and Meghan were nevertheless involved, given the level of detail in the book.

According to the publishers, HarperCollins, the biography has been produced with “unique access and written with the participation of those closest to the couple”.

We’ve seen this before, and it is a tale that seldom ends happily or well. In 1976, John Wheeler-Bennett, official biographer of George VI, observed royal biography is

not to be entered into advisedly or lightly; but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly and in the fear of God.

Wheeler-Bennett was here referring to the role of the royal biographer, but could just as easily have been referring to the royals themselves.

The royals are not supposed to go on the record and speak of private matters. The dictum ruling the House of Windsor for the best part of the 19th and 20th centuries was they should “never explain, never complain”.

In 1947, when hearing of a former servant’s plans to write about her time in royal service, the Queen Mother summed up the royal family’s strong expectations when she said:

people in positions of confidence with us must be utterly oyster.

Subsequently, the royal family was dismayed when the Duke of Windsor fed his story to a ghostwriter in 1951’s A King’s Story, outlining his own version of the abdication crisis. Prince Philip also disapproved strongly of Prince Charles’s candid revelations in Jonathan Dimbleby’s 1994 book Prince of Wales: A Biography and subsequent interview.

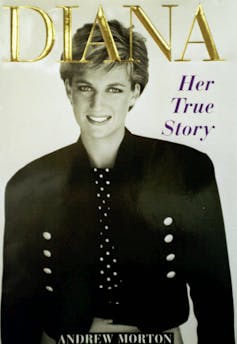

Prince Harry could also have learned some valuable lessons from his own mother, who flouted the “utterly oyster” rule.

Diana, Princess of Wales, was behind the most famous royal biography of all time when she commissioned Andrew Morton to “ghost” her tale of marital woe and royal suffering with the 1992 tell-all Diana: Her True Story.

Her True Story was a huge commercial success – having sold more than ten million copies as of 2017. But after the book’s publication, Buckingham Palace and conservative media outlets went after Morton, expressing disbelief a royal princess would talk to a tabloid journalist with no official royal biographer status.

After publicly eviscerating Morton, and the airing of Diana’s explosive 1995 Panorama interview, the palace and establishment then went after Diana. Conservative MP and close friend of Prince Charles, Nicholas Soames, claimed she must have been “in the advanced stages of paranoia” to have been disclosing the types of things she had.

Read more:

Diana revived the monarchy – and airing old tapes won’t change a thing

Diana thought Her True Story would act as a passport to freedom. She hoped it would help her separate from the royals, while keeping her privileges intact. As journalist Tina Brown wrote in her 2007 book, The Diana Chronicles, the princess thought she would get to keep all

the good bits of being a princess and doing her own global thing without Charles around to cramp her style. She did not factor in the power of royal disapproval and its consequences.

Nor did she factor in “the risk of … the Palace ‘going nuclear’ and continuing until there [is] nothing left”.

Critically, Diana had thought the revelations in Her True Story would invite her estranged royal relations’ sympathy. As Brown also notes,

she had been so long in her private panic room she thought this deafening public scream would solve the matter once and for all.

Brown records how Diana quickly regretted the book, telling her friend David Puttnam shortly before the book’s release in 1992,

I’ve done a really stupid thing. I have allowed a book to be written. I felt it was a good idea, a way of clearing the air, but now I think it was a very stupid thing that will cause all kinds of terrible trouble.

Diana was right. The biography and the Panorama interview hastened Diana’s exit from the royal enclosure. This gave her a short spell of relief and exultation. But this was followed by unhappiness that she had to live, in effect, in exile.

With release of another sensational royal biography – that very much gives one side of the story – the parallels between Diana and her son are uncanny.

Harry and Meghan obviously already have a rocky relationship with the palace, given their split with the royal family in March.

Their latest public pronouncement about their “true story” (albeit via interlocutors) is the latest salvo being fired in the long-running soap opera known as “The Windsors”. It has obviously been made to try to win a public relations war. Indeed, public relations is what the royals do. They don’t have “jobs” as such, but merely have to be “seen to be”.

Finding Freedom might have felt like a good idea to the Sussexes — an opportunity to set the record straight – but as Diana’s experience suggests, they may well come to regret the opening of their particular oyster of royal rage.

Their contribution of yet another chapter to the Windsor soap is one that will likely prove unstoppable, insatiable even. And one thing is almost certain: Harry and Meghan will very probably lose any editorial control they thought they had over their own story.

Read more:

The Crown series 3 review: Olivia Colman shines as an older, frumpier Elizabeth

![]()

Giselle Bastin, Associate Professor of English, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Irene Gammel, Ryerson University

We rarely associate youth literature with existential crises, yet Canada’s youth literature offers powerful examples for coping with cultural upheaval.

As a scholar of modernism, I am familiar with the sense of uncertainty and crisis that permeates the art, literature and culture of the modernist era. The modernist movement was shaped by upheaval. We will be shaped by COVID-19, which is a critical turning point of our era.

Societal upheaval creates a literary space for “radical hope,” a term coined by philosopher Jonathan Lear to describe hope that goes beyond optimism and rational expectation. Radical hope is the hope that people resort to when they are stripped of the cultural frameworks that have governed their lives.

The idea of radical hope applies to our present day and the cultural shifts and uncertainty COVID-19 has created. No one can predict if there will ever be global travel as we knew it, or if university education will still to be characterized by packed lecture halls. Anxiety about these uncertain times is palpable in Zoom meetings and face-to-face (albeit masked) encounters in public.

So what can literature of the past tell us about the present condition?

Consider Canadian author L.M. Montgomery, a master of youth literature. In her books, Montgomery grapples with change. She provides examples of how youth’s visions and dreams shape a new hopeful future in the face of devastation. I have read and taught her novels many times. However unpacking her hope-and-youth-infused work is more poignant in a COVID-19 world.

Her pre-war novel Anne of Green Gables represents a distinctly optimistic work, with a spunky orphan girl in search of a home at the centre. Montgomery’s early work includes dark stories as subtexts, such as alluding to Anne’s painful past in orphanages only in passing. Montgomery’s later works place explorations of hope within explicitly darker contexts. This shift reflects her trauma during the war and interwar eras. In a lengthy journal entry, dated Dec. 1, 1918, she writes, “The war is over! … And in my own little world has been upheaval and sorrow — and the shadow of death.”

COVID-19 has parallels with the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed more than 50 million people and deepened existential despair. Montgomery survived the pandemic. In early 1919, her cousin and close friend Frederica (Frede) Campbell died of the flu. Montgomery coped by dreaming, “young dreams — just the dreams I dreamed at 17.” But her dreaming also included dark premonitions of the collapse of her world as she knew it. This duality found its way into her later books.

Rilla of Ingleside, Canada’s first home front novel — a literary genre exploring the war from the perspective of the civilians at home — expresses the same uncertainty we feel today. Rilla includes over 80 references to dreamers and dreaming, many through the youthful lens of Rilla Blythe, the protagonist, and her friend Gertrude Oliver, whose prophetic dreams foreshadow death. These visions prepare the friends for change. More than the conventional happy ending that is Montgomery’s trademark, her idea of radical hope through dreaming communicates a sense of future to the reader.

The same idea of hope fuels Montgomery’s 1923 novel Emily of New Moon. The protagonist, 10-year-old Emily Byrd Starr, has the power of the “flash,” which gives her quasi-psychic insight. Emily’s world collapses when her father dies and she moves into a relative’s rigid household. To cope, she writes letters to her dead father without expecting a response, a perfect metaphor for the radical hope that turns Emily into a writer with her own powerful dreams and premonitions.

Nine decades later, influenced by Montgomery’s published writings, Jean Little wrote an historical novel for youth, If I Die Before I Wake: The Flu Epidemic Diary of Fiona Macgregor. Set in Toronto, the book frames the 1918 pandemic as a moment of both trauma and hope. Twelve-year old Fiona Macgregor recounts the crisis in her diary, addressing her entries to “Jane,” her imaginary future daughter. When her twin sister, Fanny, becomes sick with the flu, Fiona wears a mask and stays by her bedside. She tells her diary: “I am giving her some of my strength. I can’t make them understand, Jane, but I must stay or she might leave me. I vow, here and now, that I will not let her go.”

A decade later, Métis writer Cherie Dimaline’s prescient young adult novel The Marrow Thieves depicts a climate-ravaged dystopia where people cannot dream, in what one of the characters calls “the plague of madness.” Only Indigenous people can salvage their ability to dream, so the protagonist, a 16-year-old Métis boy nicknamed Frenchie, is being hunted by “recruiters” who are trying to steal his bone marrow to create dreams. Dreams give their owner a powerful agency to shape the future. As Dimaline explains in a CBC interview with James Henley, “Dreams, to me, represent our hope. It’s how we survive and it’s how we carry on after every state of emergency, after each suicide.” Here, Dimaline’s radical hope confronts cultural genocide and the stories of Indigenous people.

Radical hope helps us confront the devastation wrought by pandemics both then and today, providing insight into how visions, dreams and writing can subversively transform this devastation into imaginary acts of resilience. Through radical hope we can begin to write the narrative of our own pandemic experiences focusing on our survival and recovery, even as we accept that our way of doing things will be transformed. In this process we should pay close attention to the voices and visions of the youth — they can help us tap into the power of radical hope.![]()

Irene Gammel, Professor of Modern Literature and Culture, Ryerson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Camilla Nelson, University of Notre Dame Australia

The Australian poet Gwen Harwood used to submit poems to literary journals under both her own name and a male pseudonym, Walter Lehmann. Furious that the latter poems were more favourably received, in 1961, she sent two new sonnets to The Bulletin, penned by Lehmann, containing coded messages of abuse.

Her elaborate literary hoax became front-page news. But Donald Horne, the magazine’s editor, poured scorn on the female poet. “A genuine literary hoax would have some point to it,” he said.

In 2020, just in case this “point” is still not sufficiently clear, the Women’s Prize for Fiction has just marked its 25th anniversary by publishing 25 literary works by female authors with their real names on the cover for the first time.

Some of the books, like Middlemarch, written by Mary Ann Evans under the pen name George Eliot, are well-known, ranking among the greatest novels in English. Others have been dragged off dusty book shelves and placed in the spotlight once again.

Mary Bright, writing as George Egerton, openly talks about women’s sexuality in Keynotes, published in 1893. Ann Petry, best known as the author of The Street, the first book by an African American woman to sell more than one million copies, appears as the author of Marie of the Cabin Club, her first published short story penned under the pseudonym Arnold Petri in 1939.

Also included is Violet Paget, whose ghost story A Phantom Lover, was published under her pen name Vernon Lee. And Amantine Aurore Dupin, whose Indiana is better known for being written under the pseudonym George Sand.

For these authors, using a pseudonym was not just about slipping their work past male publishers who did not think publishing was a place for a woman. It was also about more diffuse forms of gender prejudice.

Women writers – witheringly dubbed “lady novelists” in the 19th century – also worried that their work would be marginalised as “women’s writing”; as domestic, interior, “feminine” and personal, as opposed to “masculine” themes such as history, society and politics that are, according to social norms, deemed to be more serious and culturally significant.

As George Lewes, Mary Ann Evans’ friend and life partner, put it, “the object of anonymity was to get the book judged on its own merits, and not prejudged as the work of a woman”.

In Australia, the Harwood hoax has often been relegated to the status of a literary curiosity, or mildly amusing cultural footnote. But Harwood was far from alone in feeling a sense of frustration with the male-dominated literary world.

In choosing a male pseudonym, Harwood joined the ranks of other bold and adventurous Australian women, such as Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879–1954). Franklin’s male pseudonym has been given to Australia’s most illustrious literary award, but her work – including My Brilliant Career (1901) – has not been published under her real name. The Stella Prize, established in 2013, marked this omission.

Indeed, Stella explicitly asked her publisher to delete the word “Miss” and use the name “Miles” in the hope that her work would be better received as the work of a man. “I do not wish it to be known that I’m a young girl but desire to pose as a bald-headed seer of the sterner sex,” she said.

So too, Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson (1870–1946), also known as Mrs Robertson, is only recognisable to Australian readers under the pen name Henry Handel Richardson.

Ethel used the male pseudonym to publish her literary works – including the classic women’s coming of age story, The Getting of Wisdom (1910) – because she wanted to be taken seriously as a writer.

Ethel’s gender identity was kept a secret for many years. As late as 1940 she wrote that she had chosen a man’s name because,

There had been much talk in the press of that day about the ease with which a woman’s work could be distinguished from a man’s; and I wanted to try out the truth of the assertion.

The sexually ambiguous pen name M. Barnard Eldershaw was also used by 20th century Australian writers Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw who, working in the 1920s to 1950s, penned five novels together, including Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, as well as short stories, critical essays and a radio play.

There were, of course, Australian women in the late 19th century who published under their own names, and paid the penalty.

They included Rosa Praed, Ada Cambridge, and Tasma, the pen name of Jessie Couvreur. Many were denigrated as “lady novelists” whose “romances” were witheringly labelled derivative, commercial or frivolous. And it’s likely their names are no longer recognised, except by experts.

Rosa and Ada, Stella and Ethel, for some reason, do not sound as weighty or serious as Henry and Miles, or George and Vernon. But this will not change until Australian publishers take note. It’s time to republish these Australian women under their own names.![]()

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

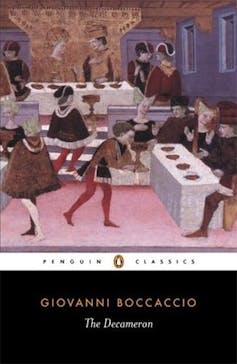

Frances Di Lauro, University of Sydney

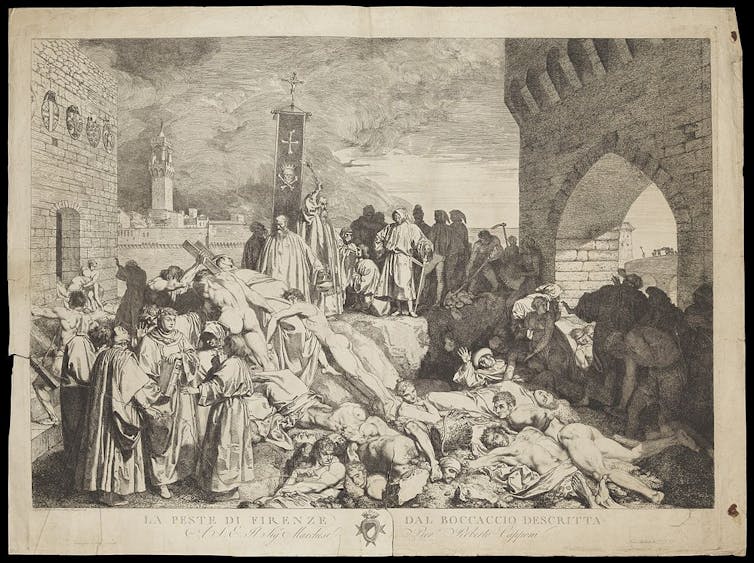

In the year then of our Lord 1348, there happened at Florence, the finest city in all Italy, a most terrible plague…

Giovanni Boccaccio introduces his acclaimed collection of novellas, the Decameron, with a reference to the most terrifying existential crisis of his time: the decimating effects of the bubonic plague in the 1348 outbreak known as the Black Death.

Boccaccio’s book, written between 1348 and 1353, has been acclaimed as an exemplar of vernacular literary prose, and a commentary on the “peste” that swept through Europe that year.

A classic of medieval plague literature, it continues to be cited by physicians and epidemiologists to this day for its vivid depiction of a disease that held a city under siege.

In the introduction to his book, Boccaccio estimates that more than 100,000 people – over half of the city’s inhabitants – died within the walls of Florence between March 1348 and the following July.

He vividly describes physical, social and psychological sufferings, writing of people dying in the street, rotting corpses, plague boils, swollen glands known as “buboes” – some the size of eggs, others as large as apples – bruises and the blackening skin that foreshadowed death.

Boccaccio’s introduction is followed by ten sections containing short stories. Each of the book’s ten storytellers tells a story a day for ten days. Derived from Greek, the word decameron means ten days and is an allusion to Saint Ambrose’s Hexameron, a poetic account of the creation story, Genesis, told over six days.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: Albert Camus’ The Plague

The Decameron is a tale of renewal and recreation in defiance of a decimating pandemic. Boccaccio attributes the cause of this terrible plague to either malignant celestial influences or divine punishment for the iniquity of Florentine society.

Unlike the plague of 1340 – which killed an estimated 15,000 Florentines – that of 1348 was, according to Boccaccio, far more contagious, spreading with greater vigour and speed.

It was extraordinary, in his view, that the disease did not merely spread from human to human but crossed species too. He saw two pigs dying within moments of biting infected clothing in the street.

Florentine officials removed household waste and contaminants from the city in attempts to eradicate the deadly pestilence, and banned infected people from entering.

They issued public pleas and advised residents on measures that would minimise risk of contagion, such as social distancing and increased personal hygiene.

Boccaccio, in the same introduction, takes aim at those who fled the sick to protect their own health and in doing so degraded the social fabric.

Extreme interpretations of social distancing led to people shunning neighbours and members of their extended and immediate families. In some cases, he writes, parents even deserted their children.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: how Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations can help us in a time of pandemic

While some took conservative measures – self-isolating indoors in small numbers, eating and drinking moderately and shutting out contact from the outside – others, he writes, roamed freely, gratifying their senses and meeting their desires for food, fun and sex:

…satisfying their every yearning, laughing and mocking at every mournful accident; and so they vowed to spend day and night, for they would go to one tavern, then to another, living without any rule or measure…

Others still consumed only what their bodies needed and excluded contact with the infected. But they wandered wherever they wished, carrying bunches of fragrant flowers, herbs, or spices, or wearing them across their noses in a bid to repel the infection and the offensive odour of death.

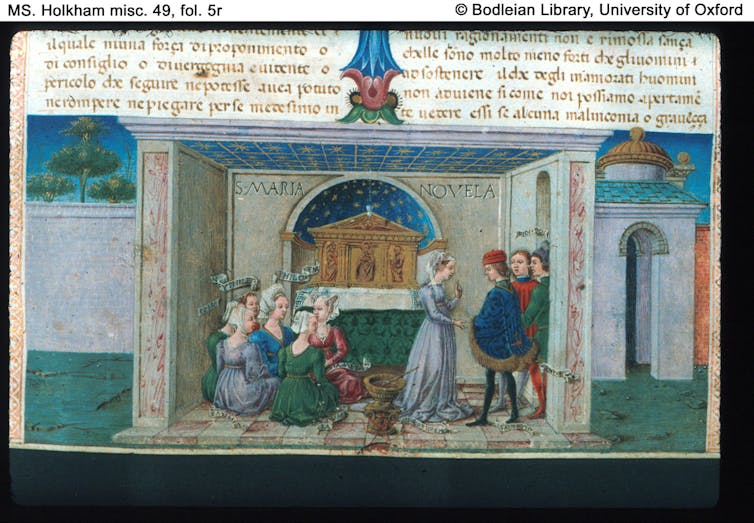

Boccaccio’s unfavourable account, lamenting moral degradation and the enormous human suffering, is interrupted by a ray of light in the form of seven young noblewomen and three young gentlemen who appear in the Church of Santa Maria Novella on a Tuesday morning.

They become the storytellers of the Decameron. Collected as a brigade (brigata), they exhibit civility, gentility, strength and a commitment to duty.

Boccaccio presents them as decorous and untarnished, having each cared for their loved ones while within the city walls. He gives each a name that suits their personal qualities, choosing monikers from his own and other literary works. They are: Pampinea, Filomena, Neifile, Filostrato, Fiammetta, Elissa, Dioneo, Lauretta, Emilia and Panfilo.

At the suggestion of the eldest noblewoman, Pampinea, the brigata leave the terrible pestilence and their devastated, plague-ridden city to take refuge in a rural villa in the nearby hills.

They are not abandoning others, she assures the group, as their relatives have either died or fled. The ten pass time by partaking in banquets, playing games, dancing, singing and telling stories.

Each member of the group narrates one story every day across the following ten days, under the supervision of the elected king or queen for the day. The proceedings close with singing and a dance.

Over those ten days, the brigata tell 100 stories. In them, they name real people – historical, contemporaries and near contemporaries – who would have been recognisable to readers of the Decameron in Boccaccio’s lifetime.

This gives a semblance of reality to the stories told inside an otherwise imaginary scene. The stories reflect Boccaccio’s accounts of moral decay in Florence at the time. Corruption and debauchery abound.

Read more:

Guide to the Classics: Dante’s Divine Comedy

How then do the pastimes of the brigata bring about renewal and recreation?

The Decameron situates vices within fiction and serves as a guide for preserving the mind during physical isolation. Retreating from a stricken city to live a simple life in a communal isolation, the brigata entertain each other and by following disciplined, structured rituals, recover some of the predictability and certainty that, according to Boccaccio, had been lost.

The Decameron was the first prose masterpiece to be written in the Tuscan vernacular, making it more accessible to readers who could not read Latin. It was first distributed in manuscript form in the 1370’s and almost 200 copies were printed over the following two centuries.

The work was censured in 1564 by the Council of Trent and a “corrected” version, expunging all references to clerics, monasteries and churches, was released in 1573.

Boccaccio’s introduction to the Decameron is a frame-story – a narrative that frames another story or a collection of stories.

This form became a popular literary model for enveloping collections of short stories that blend oral storytelling and literature. Variations and borrowings are seen in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well.

The most well-known film adaptation of the Decameron is the first of a trio of masterpieces in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1971 Trilogy of Life. Showcasing ten of the 100 stories in the Decameron, it remains one of Italy’s most popular films.

The Decameron will resonate with modern readers as we grapple with the horror of our own current pandemic. The book is a prescription for psychological survival, a way of mentally distancing from terrible visions, death counts and grim economic forecasts.

Although its framing events took place over 600 years ago, the Decameron’s modern readers, like Boccaccio’s brigata, will find comfort in company and optimism and a sense of certainty in the programmed rituals it describes.

Through its 100 stories, readers can vicariously experience situations that are out of their reach. They can be entertained, find lots to laugh about, and ultimately celebrate the joy and restorative powers of storytelling itself.![]()

Frances Di Lauro, Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Studies, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at the best ebook reader for PDFs – is there one?

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/08/05/ask-the-expert-what-is-the-best-ereader-for-pdfs/

The link below is to an article that reviews the Pocketbook Color ebook reader.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/07/30/hands-on-with-the-pocketbook-color/

The link below is to an article that looks at the latest Kobo software update.

For more visit:

https://blog.the-ebook-reader.com/2020/08/11/new-kobo-software-update-4-23-released-with-design-changes/

You must be logged in to post a comment.