Charles Dickens Museum

Leon Litvack, Queen’s University Belfast

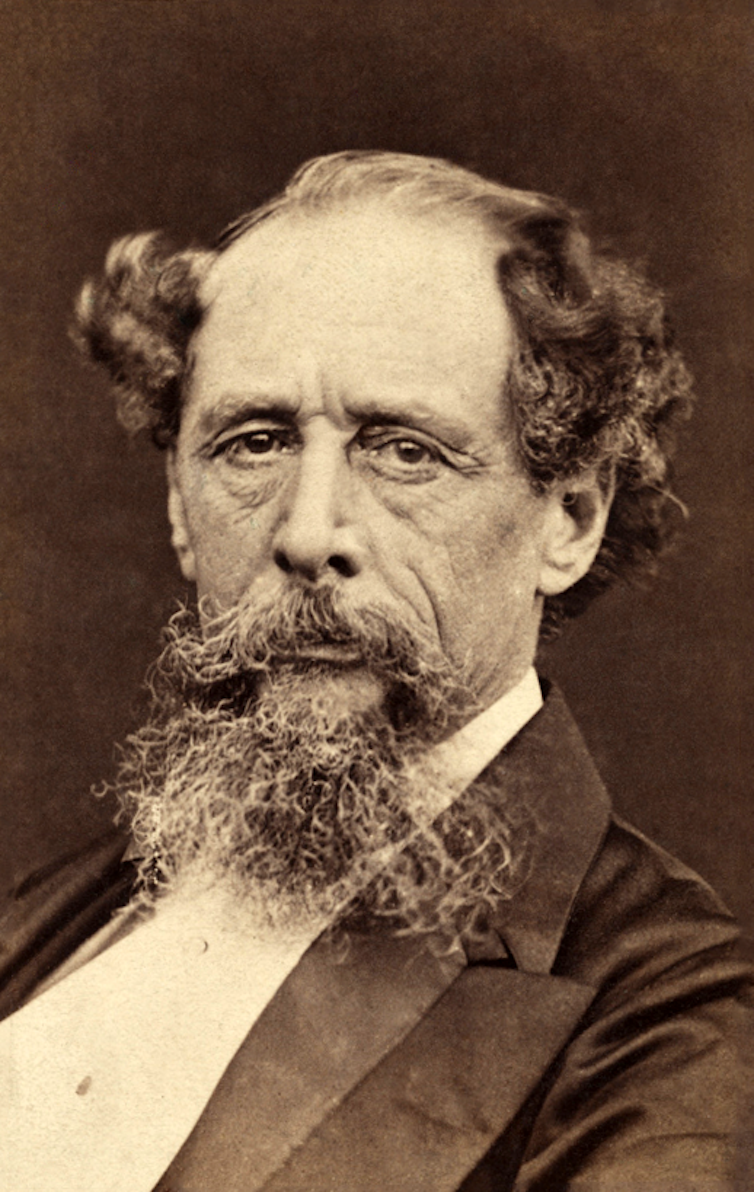

When Charles Dickens died, he had spectacular fame, great wealth and an adoring public. But his personal life was complicated. Separated from his wife and living in a huge country mansion in Kent, the novelist was in the thrall of his young mistress, Ellen Ternan. This is the untold story of Charles Dickens’s final hours and the furore that followed, as the great writer’s family and friends fought over his final wishes.

wikimedia/nationalmediamusuem, CC BY

My new research has uncovered the never-before-explored areas of the great author’s sudden death, and his subsequent burial. While details such as the presence of Ternan at the author’s funeral have already been discovered by Dickensian sleuths, what is new and fresh here is the degree of manoeuvring and negotiations involved in establishing Dickens’s ultimate resting place.

Dickens’s death created an early predicament for his family. Where was he to be buried? Near his home (as he would have wished) or in that great public pantheon, Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey (which was clearly against his wishes)?

“The Inimitable” (as he sometimes referred to himself) was one of the most famous celebrities of his time. No other writer is as closely associated with the Victorian period. As the author of such immortal classics as Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and A Christmas Carol, he was constantly in the public eye. Because of the vivid stories he told, and the causes he championed (including poverty, education, workers’ rights, and the plight of prostitutes), there was great demand for him to represent charities, and appear at public events and visit institutions up and down the country (as well as abroad – particularly in the United States). He moved in the best circles and counted among his friends the top writers, actors, artists and politicians of his day.

Dickens was proud of what he achieved as an author and valued his close association with his public. In 1858 he embarked on a career as a professional reader of his own work and thrilled audiences of thousands with his animated performances. This boost to his career occurred at a time when his marital problems came to a head: he fell in love with Ternan, an 18-year-old actress, and separated from his wife Catherine, with whom he had ten children.

Wikimedia

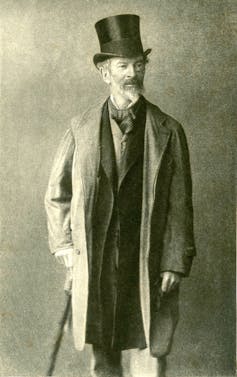

Dickens was careful to keep his love affair private. Documentary evidence of his relationship with Ternan is very scarce indeed. He had wanted to take her with him on a reading tour to America in 1868, and even developed a telegraphic code to communicate to her whether or not she should come. She didn’t, because Dickens felt that he could not protect their privacy.

On Wednesday June 8 1870, the author was working on his novel Edwin Drood in the garden of his country home, Gad’s Hill Place, near Rochester, in Kent. He came inside to have dinner with his sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, and suffered a stroke. The local doctor was summoned and remedies were applied without effect. A telegram was sent to London, to summon John Russell Reynolds, one of the top neurologists in the land. By the following day the author’s condition hadn’t changed and he died at 6.10pm, on June 9.

Accepted wisdom concerning Dickens’s death and burial is drawn from an authorised biography published by John Forster: The Life of Charles Dickens. Forster was the author’s closest friend and confidant. He was privy to the most intimate areas of his life, including the time he spent in a blacking (boot polish) warehouse as a young boy (which was a secret, until disclosed by Forster in his book), as well as details of his relationship with Ternan (which were not revealed by Forster, and which remained largely hidden well into the 20th century). Forster sought to protect Dickens’s reputation with the public at all costs.

Last Will and Testament

In his will (reproduced in Forster’s biography), Dickens had left instructions that he should be:

Buried in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner; that no public announcement be made of the time or place of my burial; that at the utmost not more than three plain mourning coaches be employed; and that those who attend my funeral wear no scarf, cloak, black bow, long hat-band, or other such revolting absurdity.

Forster added that Dickens’s preferred place of burial – his Plan A – was “in the small graveyard under Rochester Castle wall, or in the little churches of Cobham or Shorne”, which were all near his country home. However, Forster added: “All these were found to be closed”, by which he meant unavailable.

Leon Litvack

Plan B was then put into action. Dickens was set to be buried in Rochester Cathedral, at the direction of the Dean and Chapter (the ecclesiastical governing body). They had even dug a grave for the great man. But this plan too was scuppered, in favour of interment in Poets’ Corner, in Westminster Abbey – the resting place of Geoffrey Chaucer, Samuel Johnson, and other literary greats.

Forster claims in the biography that the media led the way in agitating for burial in the abbey. He singles out The Times, which, in an article of January 13 1870, “took the lead in suggesting that the only fit resting place for the remains of a man so dear to England was the abbey in which the most illustrious Englishmen are laid”. He added that when the Dean of Westminster, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, asked Forster and members of the Dickens family to initiate what was now Plan C, and bury him in the abbey, it became their “grateful duty to accept that offer”.

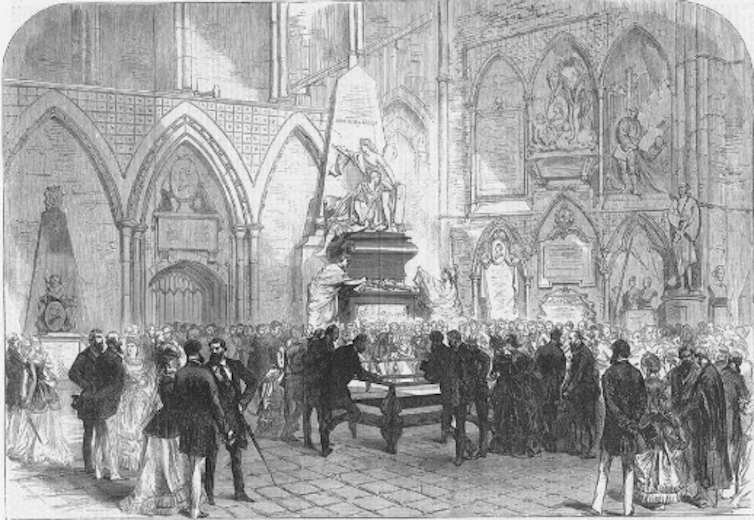

The private funeral occurred early in the morning of Tuesday June 14 1870, and was attended by 14 mourners. The grave was then left open for three days so that the public could pay their respects to one of the most famous figures of the age. Details of the authorised version of Dickens’s death and burial were carried by all the major and minor newspapers in the English-speaking world and beyond. Dickens’s estranged wife Catherine received a message of condolence from Queen Victoria, expressing “her deepest regret at the sad news of Charles Dickens’s death”.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

The effect that Dickens’s death had on ordinary people may be appreciated from the reaction of a barrow girl who sold fruits and vegetables in Covent Garden Market. When she heard the news, she is reported to have said: “Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?”

The funeral directors

My investigation has revealed, however, how Dickens’s burial in Poets’ Corner was engineered by Forster and Stanley to satisfy their personal aims, rather than the author’s own. While the official story was that it was the “will of the people” to have Dickens buried in the Abbey (and there were articles in The Times to this effect), the reality was that this alteration suited both the biographer and the churchman.

Forster could conclude the volume he was contemplating in a fitting manner, by having Dickens interred in the national pantheon where so many famous literary figures were buried. He thus ensured that a stream of visitors would make a pilgrimage to Dickens’s grave and spread his reputation far and wide, for posterity.

Stanley could add Dickens to his roll of famous people whose burials he conducted. They included Lord Palmerston, the former UK prime minister, mathematician and astronomer Sir John Herschel, missionary and explorer David Livingstone, and Sir Rowland Hill, the postal reformer and originator of the penny post.

The efforts of Forster and Stanley to get Dickens buried exactly where they wanted enhanced the reputations of both men. For each of them, the interment of Dickens in the abbey might be considered the highlight of their careers.

Charles Dickens Museum, CC BY

‘Mr Dickens very ill, most urgent’

The new evidence I have found was gathered from libraries, archives and cathedral vaults and prove beyond a doubt that any claims about the Westminster burial being the will of the people are false.

What emerges is an atmosphere of urgency in the Dickens household after the author collapsed. Dickens’s son Charley sent the telegram to the author’s staff in London, requesting urgent medical assistance from the eminent neurologist, John Russell Reynolds:

Go without losing a moment to Russell Reynolds thirty eight Grosvenor St Grosvenor Sqr tell him to come by next train to Higham or Rochester to meet… Beard (Dickens’s physician), at Gadshill … Mr Dickens very ill most urgent.

Dickens’s sister-in-law, Georgina Hogarth, who ran his household and cared for his children after the separation from Catherine, was clearly disappointed that the specialist could do nothing for her much-adored brother-in-law. She sent a note to her solicitor with the doctor’s fee: “I enclose Dr Reynolds’ demand (of £20) for his fruitless visit.”

Dean Stanley had met Dickens in 1870, after being introduced by the churchman’s brother-in-law, Frederick Locker, who was a friend of the novelist. Stanley confided to his private journal (now housed in the archives of Westminster Abbey) that he was “much struck” by his conversation with Dickens and appreciated the few opportunities he had to meet the author before he died.

Locker’s memoir also records an interesting conversation he had with Stanley before this 1870 meeting, which sheds light on the Dean’s attitude towards the novelist, his death and funeral. Locker writes about talking to Stanley “of the burials in the abbey” and they discussed the names of some “distinguished people”. Stanley told him there were “certain people” he would be “obliged to refuse” burial, on account of personal antipathies. But his attitude changed when the name of the author “came up” and he said he “should like to meet Dickens”. Then, to “gratify” Stanley’s “pious wish”, Locker asked Dickens and his daughter to dine. Thus even while Dickens was still alive, Stanley privately expressed a desire to bury him.

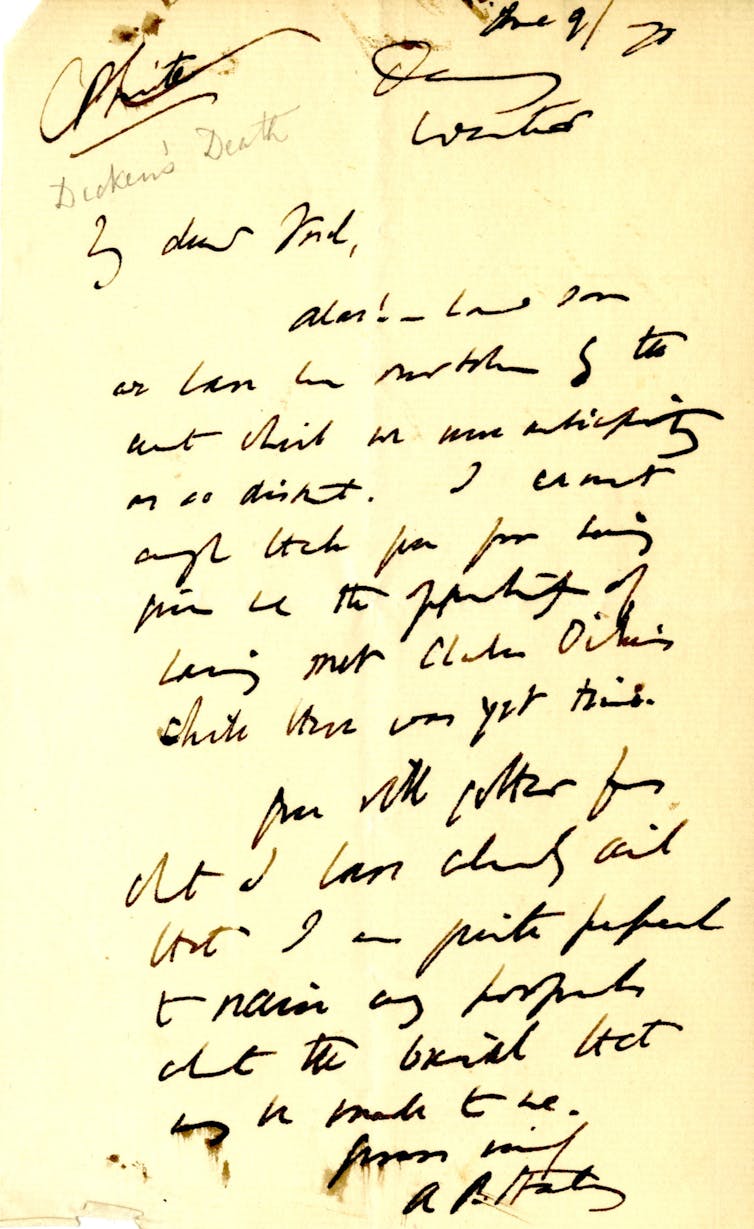

When the end came, Locker conveyed the news to his brother-in-law on that very day – June 9. The Dean wrote to Locker to say:

Alas! – how soon we have been overtaken by the event which we were anticipating as so distant. I cannot amply thank you for having given me the opportunity of having met Charles Dickens while there was yet time. You will gather from what I have already said that I am quite prepared to raise any proposals about the burial that may be made to me.

By kind permission of the Armstrong Browning Library., Author provided

The letter is fascinating. On the very day of the famous author’s death, the Dean was already thinking about burial in the Abbey. But there was a catch: Stanley could only entertain such a proposal if it came from the family and executors. He could not act unilaterally.

Locker quickly seized the opportunity hinted at in Stanley’s letter and sent a copy of it to Charley Dickens (the author’s son) on June 10. He wrote in his covering note: “I wish to send you a copy of a letter that I have just received from Dean Stanley and I think it will explain itself. If I can be of any use pray tell me.”

False claims and ambition

Meanwhile, the idea of getting Dickens to Poets’ Corner was growing in Stanley’s imagination. He wrote to his cousin Louisa on Saturday June 11 to say “I never met (Dickens) till this year… And now he is gone … and it is not improbable that I may bury him”. It’s interesting how quickly the plan crystallised in the Dean’s mind. Within the space of 48 hours, he went from hypothetical proposals from the family for burial, to foreseeing a key role for himself in the proceedings.

However, an answer from Charley Dickens wasn’t forthcoming. Stanley waited until the morning of Monday June 13, before seeking another way of making his wishes known to the family. He got in touch with his friend Lord Houghton (formerly Rickard Monckton Milnes – a poet, politician and friend of Dickens), reiterating his preparedness “to receive any proposal for (Dickens’s) burial in the Abbey” and asking Houghton to “act as you think best”.

It was at this point in the proceedings that Forster took charge of the planning. He had been away in Cornwall when Dickens died and it took him two days to reach Gad’s Hill. When he reached Dickens’s country home on Saturday June 11 he was overcome with grief at the death of his friend and clearly unprepared for the suddenness with which the blow was struck. His first thoughts, and those of the immediate family, were to accede to Dickens’s wishes and have him buried close to home. While the official account, in his Life of Dickens, claims that the graveyards in the vicinity of his home were “closed”, an examination of the records of the churches in Cobham and Shorne demonstrate this to be false.

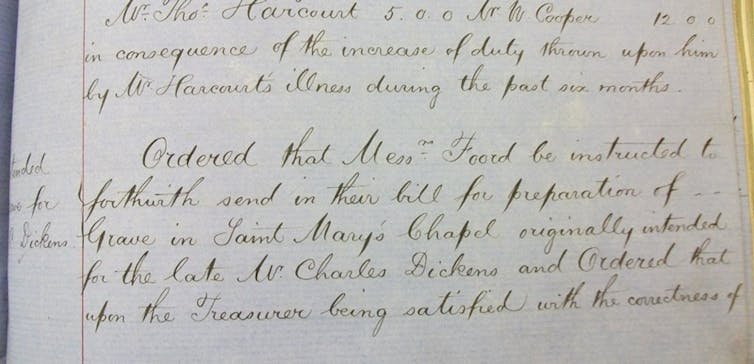

The proposed burial in Rochester Cathedral was not only advanced, but in fact finalised, costed, and invoiced. The Chapter archives demonstrate that a grave was in fact dug in St Mary’s Chapel by the building firm Foord & Sons. The records also show that the Cathedral authorities “believed, as they still believe (after Dickens was buried in the Abbey), that no more fitting or honourable spot for his sepulture could be found than amidst scenes to which he was fondly attached, and amongst those by whom he was personally known as a neighbour and held in such honour”.

Medway Archives & Local Studies., Author provided

These views are reinforced by the claims of Hogarth, Dickens’s sister-in-law, in a letter to a friend:

We should have preferred Rochester Cathedral, and it was a great disappointment to the people there that we had to give way to the larger demand.

This “larger demand” came – at least in part – from a leader that appeared in The Times on Monday June 13. It concluded:

Let (Dickens) lie in the Abbey. Where Englishmen gather to review the memorials of the great masters and teachers of their nation, the ashes and the name of the greatest instructor of the nineteenth century should not be absent.

Despite this appeal appearing in the press, Stanley’s private journal records that he still “had received no application from any person in authority”, and so “took no steps” to advance his burial plan.

Stanley’s prayers must have seemed answered, then, when Forster and Charley Dickens appeared at the door of the Deanery on that same day. According to the Dean, after they sat down, Forster said to Stanley: “I imagine the article in the ‘Times’ must have been written with your concurrence?” Stanley replied: “No, I had no concern with it, but at the same time I had given it privately to be understood that I would consent to the interment if it was demanded.” By this Stanley meant the letter he had sent to Locker, which the latter had forwarded to Charley. Stanley of course agreed to the request from Dickens’s representatives for burial in Poets’ Corner. What he refrains from saying is how much he personally was looking forward to officiating at an event of such national significance.

While it’s clear, from the private correspondence I have examined, that Stanley agitated for Dickens’s burial in the abbey, the actions of Forster are harder to trace. He left fewer clues about his intentions and he destroyed all of his working notes for his monumental three volume biography of Dickens. These documents included many letters from the author. Forster used Dickens’s correspondence liberally in his account. In fact, the only source we have for most of the letters from Dickens to Forster are the passages that appear in the biography.

But as well as showing how Forster falsely claimed in his biography that the graveyards near his home were “closed”, my research also reveals how he altered the words of Stanley’s (published) funeral sermon to suit his own version of events. Forster quoted Stanley as saying that Dickens’s grave “would thenceforward be a sacred one with both the New World and the Old, as that of the representative of the literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue”. This, however, is a mis-quotation of the sermon, in which Stanley actually said:

Many, many are the feet which have trodden and will tread the consecrated ground around that narrow grave; many, many are the hearts which both in the Old and in the New World are drawn towards it, as towards the resting-place of a dear personal friend; many are the flowers that have been strewed, many the tears shed, by the grateful affection of ‘the poor that cried, and the fatherless, and those that had none to help them’.

Stanley worked with Forster to achieve their common aim. In 1872, when Forster sent Stanley a copy of the first volume of his Life of Dickens, the Dean wrote:

You are very good to speak so warmly of any assistance I may have rendered in carrying out your wishes and the desire of the country on the occasion of the funeral. The recollection of it will always be treasured amongst the most interesting of the various experiences which I have traversed in my official life.

Leon Litvack

For the ages

My research demonstrates that the official, authorised accounts of the lives and deaths of the rich and famous are open to question and forensic investigation – even long after their histories have been written and accepted as canonical. Celebrity is a manufactured commodity, that depends for its effect on the degree to which the fan (which comes from the word “fanatic”) can be manipulated into believing a particular story about the person whom he or she adores.

In the case of Dickens, two people who had intimate involvement in preserving his reputation for posterity were not doing so for altruistic reasons: there was something in it for each of them. Stanley interred the mortal remains of Dickens in the principal shrine of British artistic greatness. This ensured that his tomb became a site of pilgrimage, where the great and the good would come to pay their respects – including the Prince of Wales, who laid a wreath on Dickens’s grave in 2012, to mark the bicentenary of his birth.

Such public commemorations of this Victorian superstar carry special meaning and mystique for his many fans. This year, on February 7 (the anniversary of his birth), Armando Iannucci (director of the new film adaptation The Personal History of David Copperfield) is scheduled give the toast to “the immortal memory” at a special dinner hosted by the Dickens Fellowship – a worldwide association of admirers. The 150th anniversary of his death will be observed at Westminster Abbey on June 8 2020.

Whether it’s the remembrance of the author’s death or his birth, these public acts symbolise how essential Dickens is to Britain’s national culture. None of this would have been possible, however, had it not been for the involvement of Dickens’s best friend and executor, John Forster. Forster organised the private funeral in Westminster Abbey in accordance with Dickens’s wishes, and ensured that his lover Ellen Ternan could discreetly attend, and that his estranged wife would not. But he is also the man who overruled the expectations of the author for a local burial. Instead, through an act of institutionally sanctioned bodysnatching, the grave in Poets’ Corner bound Dickens forever in the public mind with the ideals of national life and art and provided a fitting conclusion to Forster’s carefully considered, strategically constructed biography. It ends with these words:

Facing the grave, and on its left and right, are the monuments of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Dryden, the three immortals who did most to create and settle the language to which Charles Dickens has given another undying name.

For you: more from our Insights series:

-

The end of the world: a history of how a silent cosmos led humans to fear the worst

-

Decades neglecting an ancient disease has triggered a health emergency around the world

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Leon Litvack, Associate Professor, Queen’s University Belfast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.