The link below is to an artcile that contains a host of ifographics concerning the Emily Bronte novel, ‘Wuthering Heights.’

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/jul/30/emily-brontes-wuthering-heights-in-charts

The link below is to an artcile that contains a host of ifographics concerning the Emily Bronte novel, ‘Wuthering Heights.’

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2018/jul/30/emily-brontes-wuthering-heights-in-charts

Claire Nally, Northumbria University, Newcastle

Following the announcement that Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina is the first graphic novel ever to be longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Joanne Harris (the author of Chocolat) tweeted #TenThingsAboutGraphicNovels and stated simply: “graphic novels are novels”.

Once upon a time, graphic novels may have been viewed as disposable – and not especially literary – but such a value judgement has long since been challenged.

The graphic autobiography has become especially visible in recent years, with a noteworthy example being Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (2000) – which details her experiences as a young woman during and after the Iranian revolution in 1979. The novel was adapted into a film in 2007.

The comic book has a long and rich history, as Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics explains. He looks at a pre-Columbian text from the Codex Nuttall about 8-Deer “Tiger’s Claw”, discovered by the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortés around 1519. McCloud argues we can think about such early texts as comics.

Terminology is important here, too. The word “comics” usually refers to serialised publications – whereas “graphic novels” are issued as books. That said, they share many artistic and literary characteristics. Author Alan Moore has rejected the term “graphic novel” (along with the film versions of his work), suggesting it is nothing more than a marketing term. So, in no particular order – and with that caveat in mind – here are my top five literary reads in graphic novel and comic book genres.

Author Bryan Talbot is well-known to comic and graphic novel fans, having penned The Adventures of Luther Arkwright in the 1970s and 1980s. Grandville is the first volume in a series of five, which tells the investigative story of a badger detective, Detective Inspector LeBrock, accompanied by his trusty sidekick, Roderick the Rat.

In this anthropomorphic universe, humans feature in servile roles as an underclass, with some critical comparisons to post-9/11 racial stereotypes. The Grandville of the title is an alternative history Paris, lovingly characterised with steampunk details and Belle Époque style. The city of Grandville takes its name from the pseudonym of a French artist, Gérard Grandville, famed for his satire of French politics and society.

The book wears its intellectualism lightly – but, for those with a keen eye, look out for cultural references to Édouard Manet, Augustus Egg, Sarah Bernhardt, and intertexts such as Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, as well as children’s classics including Wind in the Willows, Tintin and Rupert the Bear.

Alan Moore needs little introduction to cult readers or the academic community. He has amassed a wealth of literary criticism about his work, including plenty of material about the title I have chosen, From Hell. This was originally issued in serial form and later published as a single-volume collected work – the version with which most readers will be familiar.

From Hell is not for the squeamish: it retells in gruesome detail the Whitechapel murders of the late 19th century, speculating Jack the Ripper was Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria’s royal physician. Gull’s murder spree, seeking to suppress an illegitimate heir to the throne and filtered through a lens of masonic imagery and misogyny, takes us through a psychogeographic tour of London.

Eddie Campbell’s exquisite illustrations contrast the privileged suburbs in which Gull lives with the poverty-stricken degradation of Whitechapel’s citizens.

Partly fictional and partly factual, the book is a wonderful parody of the dark tourist interest in the murders, with the careful reader becoming increasingly self-conscious of their own uncomfortable complicity in the narrative.

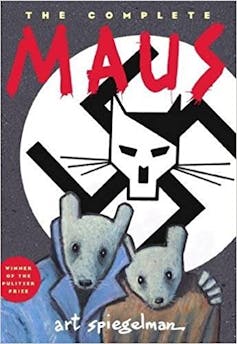

Like From Hell, Art Spiegelman’s Maus was originally published in serial form. Spiegelman began writing in 1978, telling the story of his father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Holocaust survivor.

In many ways, the text defeats simplistic categories and genres: it is a fiction, an autobiography and a history.

It is also another anthropomorphic story in which Nazis are cats and the Jewish community are characterised as mice. The reader is placed in the unenviable but important position of bearing after-witness to the trauma of the Nazi regime, a point enhanced by the use of literary devices such as the framing narrative.

Spiegelman uses the more recent moment of the late 1970s and interviews with his elderly, widowed father as a departure point to revisit the 1930s through to the end of the Holocaust in 1945.

Spiegelman’s book won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

Sydney Padua’s witty black-and-white graphic novel describes itself as “an imaginary comic about an imaginary computer”. It foregrounds Ada Lovelace’s contribution to Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, the herald of our modern computers.

Like other examples here, the narrative is situated in an alternative universe, which offers a view of what would happen if the Difference Engine had been built. Along with an adventure plot, the graphic novel features references to a wealth of 19th–century characters such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Duke of Wellington. It has elaborate pseudo-factual footnotes and endnotes of which writers such as Flann O’Brien or Mark Z. Danielewski would be proud.

It would be very remiss of me, as a longstanding aficionado of James Joyce, to omit reference to this Costa award-winning graphic memoir by Mary M. Talbot (with illustrations by Bryan Talbot, the writer’s husband), which follows Lucia Joyce’s troubled relationship with her father, and draws parallels with the author’s own relationship with her father, the eminent Joyce scholar James S. Atherton.

Read more:

Guilty Pleasures: an English literature professor’s secret stash of graphic novels

Lucia’s tragic love for Samuel Beckett – and her thwarted ambition to become a dancer – are beautifully juxtaposed with Talbot’s recollections of her upbringing, alongside the difficulties experienced by both talented women growing up with writerly fathers. Strategic use of colour, sepia tones and the frequent use of the Courier typeface (as well as Talbot’s own personal lettering font which features throughout his work), make this book an aesthetically delightful read.

Of course, there are many artists and writers I have omitted from this list – not least figures such as Neil Gaiman, whose work The Sandman (1989-) has been critically acclaimed, pushing as it does the Gothic tropes and metaphysical reflections of the genre.

For those of a humorous inclination, Kate Beaton’s webcomic Hark, A Vagrant (published as a book in 2011) is an affectionately irreverent look at literature and history, including the hilarious Dude Watchin’ With the Brontës.

![]() There are also the recent works lauded in the Will Eisner Comic Awards, held earlier this month in San Diego as part of Comic-Con. Further reading can be found on that list.

There are also the recent works lauded in the Will Eisner Comic Awards, held earlier this month in San Diego as part of Comic-Con. Further reading can be found on that list.

Claire Nally, Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century English Literature, Northumbria University, Newcastle

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the discovery of an ancient library in Cologne, Germany.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/31/spectacular-ancient-public-library-discovered-in-germany

The link below is to an article reporting on the latest news from the PEN America Literary Awards.

For more visit:

https://publishingperspectives.com/2018/07/pen-america-announces-refocused-short-story-debut-robert-bingham-prize/

The links below are to articles reporting on a controversy concerning a suggestion that Amazon should replace libraries.

For more visit:

– https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/23/twaddle-librarians-respond-to-suggestion-amazon-should-replace-libraries

– https://the-digital-reader.com/2018/07/22/amazon-books-should-replace-local-libraries-and-other-publisher-serving-solutions/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2018 Commonwealth Short Story Prize. The winner was ‘Trinidadian Creole,’ by Kevin Jared Hosein.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jul/25/trinidadian-creole-tale-wins-2018-commonwealth-short-story-prize

David Anderson, Swansea University

The British economy was in a volatile state 80 years ago, as the world teetered on the brink of war. Business was tough for all, and yet printing and publishing was expanding with Dundee-based DC Thomson & Co, publisher of newspapers, magazines and comics, especially prominent.

Spurred on by the success of weekly newspaper comic strips Oor Wullie and The Broons, and its “big five” action story papers for boys, Thomson decided in 1937 to create another quintet of comics for boys and girls, this time focused on humour.

The Dandy became the first of these comics to launch in December 1937, featuring characters Korky the Cat, Keyhole Kate, Hungry Horace and the enduring Desperate Dan. Under the editorship of the indomitable Albert Barnes (whom the square-jawed Desperate Dan is said to be modelled on), The Dandy introduced a new style of comic drawing to generations of schoolchildren. Taking inspiration from existing British and American styles, such as the use of hand drawn speech bubbles, The Dandy’s team of experienced scriptwriters and talented artists developed a humour that celebrated slapstick and derided authority figures.

The following summer, a “great new fun paper” arrived – The Beano. Now close to publishing its 4,000th edition, the very first issue of The Beano came complete with a free whoopee mask when it was released on July 30, 1938. Deriving its name from a 19th century colloquialism for celebration, party, or other merry occasion, The Beano was intended to be a feast of fun.

The 28-page publication was a mixture of mostly black and white comic stories, short comic strips, and text stories. With characters such as Big Eggo (an inquisitive ostrich), Lord Snooty (and his pals), and Pansy Potter (the strong man’s daughter), The Beano enjoyed an immediate readership, with 442,963 copies of the first issue sold.

It wasn’t just about the laughs. During World War II, The Dandy and The Beano became important propaganda tools in the fight against Nazism and Fascism. Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göering, and Benito Mussolini were lampooned in each comic, and copies of The Beano were sent to soldiers serving overseas to boost morale.

Scripts and advertisements followed patriotic themes, too, urging readers to aid the war effort on the home front by gathering waste paper for recycling. Lord Snooty’s storylines often reminded children of the importance of gas masks for protection against chemical attack during air raids. Thrilling adventure stories, such as Tom Thumb, and Jimmy and His Magic Patch, enthralled war-weary readers with fantastic escapist tales in far flung, fairytale locations.

The war scattered Beano artists and writers far and wide, while paper rationing and ink shortages forced a smaller page count. Yet publication continued, albeit fortnightly, alternating with The Dandy.

A third pre-war Thomson comic, The Magic, which launched a few weeks before the outbreak of hostilities, ceased publication in 1941 because of paper scarcities. Thomson’s ambition to create another big five was never fully realised.

After the war, The Beano staff returned with renewed energy and enthusiasm, successfully taking on new comics such as The Eagle (1950), also published in Britain, and the competing medium of TV. Circulation increased dramatically – in April 1950, The Beano reached the peak of its popularity, recording a weekly sale of 1,974,072, the highest to date, for issue 405.

In 1948, Biffo the Bear ousted Big Eggo from the front cover after market research indicated children preferred their cartoon strip characters to more closely resemble people. It was an important moment in the comic’s history, when many of The Beano’s longest running stories, focused on child characters, full of tricks and tomfooleries, began to appear for the first time in all their mischievous, madcap magnificence. One such character was the “world’s wildest boy”, Dennis the Menace, who burst onto the pages of The Beano in 1951.

In 1953, artist Leo Baxendale brought to life The Bash Street Kids, Little Plum, and Minnie the Minx, with Roger the Dodger, by Ken Reid, also debuting that year. In the 1960s and 70s, further new characters were introduced, including Billy Whizz (“the world’s fastest boy”) and Baby-Face Finlayson (“the cutest bandit in the west”).

Since the 1980s, Beano storylines have increasingly reflected shifting social trends, and adjustments have been made to the language and look of characters. Dennis, for example, is no longer known as a menace and his nemesis, Walter, is no longer a “softy”.

While the digital age has undoubtedly impacted sales, The Beano has, for the most part, embraced the challenges, and is now available online as well as in print. Now the world’s longest running weekly comic (following the demise of The Dandy in 2012), The Beano has endured because it celebrates its past, while evolving to survive the future.

![]() The comic has entertained children and adults for more than three generations, a riotous celebration of comic art, anarchy and absurdity. It is part of Britain’s individual and collective memory, part of the fabric of its social and cultural history. Happy Birthday, Beano!

The comic has entertained children and adults for more than three generations, a riotous celebration of comic art, anarchy and absurdity. It is part of Britain’s individual and collective memory, part of the fabric of its social and cultural history. Happy Birthday, Beano!

David Anderson, Senior Lecturer in American History, Swansea University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.