Daily Archives: 27 August 2018

VS Naipaul: a man who cast doubt on post-colonial liberal certainties

EPA

Dilip Menon, University of the Witwatersrand

No author in contemporary times more wilfully damaged his reputation with cantankerous observations as did VS Naipaul. He had extreme and contrarian opinions on the big issues of the day, from colonialism to Islam and the travesties of nationalism in Asia and Africa.

A generation of readers who came of age in the last decade of the 20th century saw, and heard, him at his worst, even as his literary career was capped with the ultimate accolade of the Nobel Prize in 2001. The citation emphasised his,

perceptive narrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories.

But it must have seemed incomprehensible to those who had only listened to his intemperate words and read his later work which seemed like tired caricatures of his earlier oeuvre.

Colonial history

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul’s early life was lived in the detritus of the colonial history of indenture and the vast forced movement of people from the South Asian subcontinent to Africa and the Caribbean. Between 1833 (the abolition of slavery) and 1922, 3.5 million Indians were transported under a system of debt bondage to work on sugar plantations in European colonies.

The memory of Indian civilisation was scattered along an archipelago of labour across two oceans – the Indian and the Pacific. Men and women living in countries as disparate as South Africa, Trinidad and Fiji were trapped in small lives of drudgery, gossip and congealed tradition yet still aspiring to a life of the mind.

Vidia’s father Seepersaud Naipaul was the first Indo-Trinidadian reporter for the Trinidad Guardian. He wrote short stories that he hoped would be published in London and lift the family from its genteel poverty. He, and his sons, Vidia and Shiva, mined the messy intricate lives around them for affectionate and searing portrayals of ambition, intrigue and ennui within the Indo-Trinidadian community.

Never has so small a community been mined for so large a literary canvas. A House for Mr Biswas, Flag on the Island, The Suffrage of Elvira, The Mystic Masseur, and his brother Shiva’s Chip Chip Gatherers and Fireflies were the first great novels coming out of the history of indenture.

Both Vidia and Shiva went up to Oxford, but their writing was both an act of faith to their origins as much as an act of treason against the language bequeathed them by Empire. Naipaul’s early novels affectionately and grittily recreated the Indo-Trinidadian argot at a time when postcolonial writing was marked by the well-behaved cadences of the Queen’s English. This act of temerity is often forgotten, as every word committed treason against a colonial enterprise of education.

Characters that spoke to the world

His novels were not simply quaint local evocations as became clear in the literary accolades that came his way so easily. Mr Biswas (A House for Mr Biswas 1961), Ganesh Ramsumair in The Mystic Masseur (1957) (who would retitle himself Ramsay Muir) and others were characters that spoke to the world much as did characters from the books of French literary artist Balzac: small people who occupied the world in large ways.

It’s worth remembering that this act of rendering the register of Trinidadian lives as universal marks an ambition that few postcolonial writers possess even today. Indian and African writers in English write correct, unambitious prose where the register of local English is always rendered as comical. This embarrassment is evident even in Salman Rushdie’s “chutnified” English which bears no relation to forms of English spoken anywhere in India, but is a form of caricature that marks the yawning distance between the writer and the landscape that he occupies.

Indo-Anglian writers are most comfortable in ventriloquising their own class. Naipaul’s characters and their speech are not the result of mere acute observation, but of a location within a matrix of social relations.

This attention to, and affection for, the odd and the eccentric, even repugnant, individual characterised his later move into a higher journalism in books like India: A Million Mutinies Now (1990) and his closely observed travel account of the southern states of the US, A Turn in the South (1989). He is able to summon up the fertile anarchy of one space and the underlying melancholy of the other through fine-grained conversations, attentive to every word spoken even by people lost to the national imagination.

The epigraph to A Turn in the South is from Shakespeare:

There is a history in all men’s lives.

What irritated critics bred on liberal hypocrisy was the fact that Naipaul wore his opinions on his sleeve. Even as he lavished a single-minded devotion to the rhythms of speech of his interlocutors, and rendered their selves in an uncannily distinctive fashion, he never held back on his disappointment on what could have been.

The experience of having pulled himself up from a narrow world meant that he judged harshly; even himself. Readers of his letters to his father from Oxford Between Father and Son (2000) are exposed to a self-indulgent, self-pitying and entitled son. He’s prodigal in every way, writing, and not often, to a father who waited to live vicariously, through every letter, a life that he could never have had.

Naipaulian credo

Naipaul was hard on himself as on others. Patrick French, in his magisterial biography titled it with the Naipaulian credo: The world is what it is. One made one’s life or one didn’t. It was the harsh lesson of someone for whom the experience of indenture was one generation away.

What lay behind his novels – set in Africa – as well as his historical accounts of the Caribbean, was what he saw as the refusal of the postcolonial citizen to take the world for what it was, and move on.

He saw both the coloniser and colonised as wrapped in sentimental nostalgia for what might have been. The Middle Passage and The Loss of El Dorado are as much about the overweening ambition and rapacity of the Europeans as much as their failure. And the inept violence of the coloniser was mirrored in the inability of the colonised to come into their own.

When he wrote An Area of Darkness in 1964, it was too close to the euphoria of independence for Indian elites to accept. It prompted prissy nationalist ripostes, like that of the poet Nissim Ezekiel who accused Naipaul of solipsism, that

he wrote exclusively from the point of view of his own dilemma.

Time has shown that the dilemma stains all Indian thought, the burden of a non-modernity.

On Naipaul’s passing, another Indian poet, Keki Daruwalla, was to write about him that he was like

a mother bird rummaging in a nest of doubts.

And doubt about liberal certainties and postures was what Naipaul left us with, even as he devoted his entire focus and lapidary prose to the little people.

<!– Below is The Conversation's page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. –>

![]()

VS Naipaul, writer, born 17 August 1932; died 11 August 2018.

Dilip Menon, Mellon Chair of Indian Studies and the Director of the Centre for Indian Studies in Africa, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Best Books on Madonna

The link below is to an article that looks at the best books on Madonna (who recently turned 60).

For more visit:

https://pitchfork.com/features/lists-and-guides/these-are-the-best-madonna-books/

Fan Fiction

The link below is to an article that takes a look at fan fiction by way of an ‘open letter.’

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/08/21/open-letter-to-fanfiction/

Humphrey Llwyd: the Renaissance scholar who drew Wales into the atlas, and wrote it into history books

The Library of Congress/Wikimedia

As a small country with less than 5% of the UK population, Wales faces major challenges in making its presence felt in the wider world – but this is something that scholars, politicians and the people themselves have been concerned about for centuries.

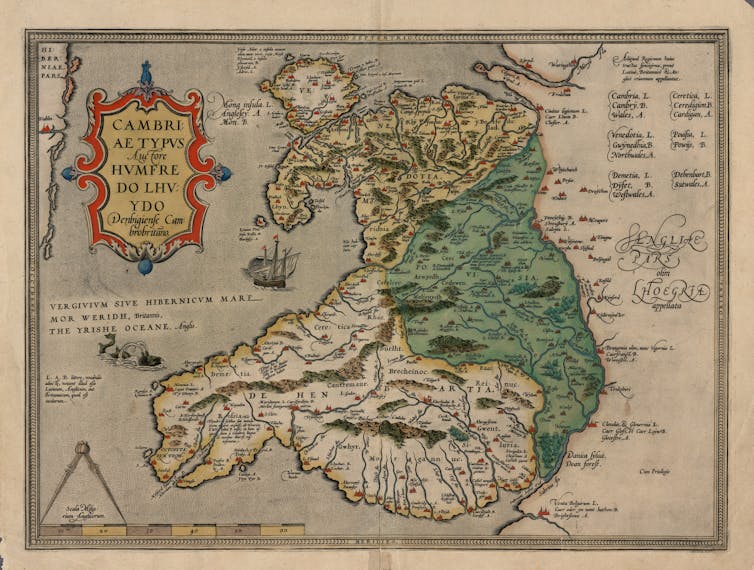

August 2018 marks the 450th anniversary of the death of Humphrey Llwyd, a remarkable Renaissance scholar who believed that Wales was fundamental to the history and identity of Britain. Llwyd not only drafted the first published map of Wales – which literally set the country on a global stage – but was the first person to write a history of Wales and a topographical account of Britain.

Born to a gentry family in Denbigh in 1527 and educated at Oxford, Llwyd went on to make his career in England, being employed in the household of the cultured and book-loving Henry Fitzalan, the 12th Earl of Arundel. This gave Llwyd the opportunity to develop his interest in learning. It also led to his marriage to Barbara, sister of the earl’s son-in-law, Lord Lumley (who himself was another enthusiastic book collector).

Philip Yorke/Wikimedia

By 1563 Llwyd had set up home back in Denbigh, within the walls of the town’s medieval castle. As MP for the borough, he reportedly facilitated the passage, through the parliament of 1563, of the bill authorising the translation of the Bible and Book of Common Prayer into Welsh.

In 1566–7 Llwyd joined Arundel on a journey to Italy. However, a little over a year after his return to Denbigh, he fell seriously ill, and died on August 21 1568. He was buried just outside the town at the church of Llanfarchell, where the fine monument erected to his memory can still be seen.

Mapping Wales

Like other Welsh Renaissance scholars, Llwyd welcomed the so-called “union” of Wales and England under Henry VIII. Yet precisely because the future of Wales lay in the wider orbit of Britain Llwyd was determined to promote its history and culture as integral parts of the island’s heritage.

That determination was sharpened by his experiences outside Wales. It is no coincidence that the first work conceived of as a history of Wales – Llwyd’s Cronica Walliae (“The Chronicle of Wales”) of 1559 – was written in England, very probably at Arundel’s palace of Nonsuch near London for antiquarian-minded members of the earl’s circle. (Despite its Latin title, the work was written in English.)

The chronicle struck a defiant tone:

I was the first that tocke the province [Wales] in hande to put thees thinges into the Englishe tonge. For that I wolde not have the inhabitantes of this Ile ignorant of the histories and cronicles of the same, wherein I am sure to offende manye because I have oppenede ther ignorance and blindenes thereby …

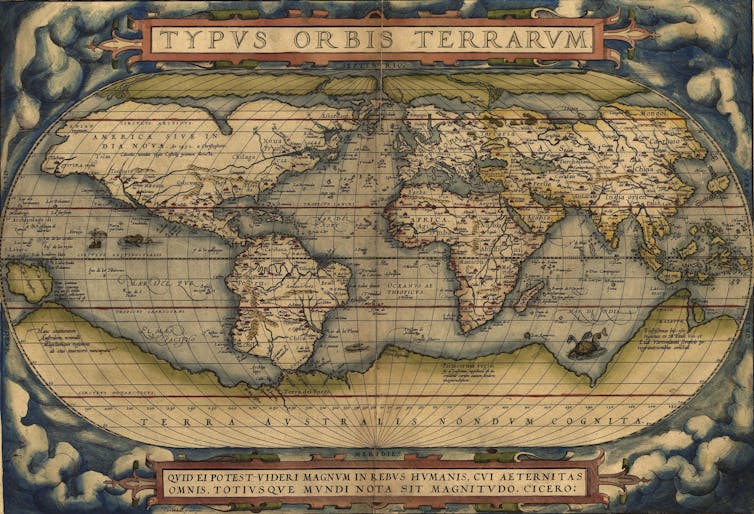

Llwyd’s final works resulted from commissions by the great Flemish cartographer and “inventor” of the atlas, Abraham Ortelius, whom Llwyd met at Antwerp on his way home from Italy in 1567. These included two maps, one of Wales, the other of England and Wales, which were eventually published in a supplement to Ortelius’s atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (“Theatre of the World”), in 1573.

National Library of Wales

Llwyd sent drafts of these from his deathbed in Denbigh, along with notes on the topography of Britain – Commentarioli Britannicae descriptionis fragmentum (“A Fragment of a Little Commentary on the Description of Britain”) – written in Latin and published in Cologne in 1572. This was soon followed by Thomas Twyne’s English translation, The Breviary of Britayne (1573). Significantly, about half of the work was devoted to Wales.

Defending history

One aim of the Breviary was to defend the traditional British history popularised by Geoffrey of Monmouth – which traced the earliest kings of Britain to the Trojan exile Brutus – against the Italian humanist historian Polydore Vergil, “who sought not only to obscure the glory of the British name, but also to defame the Britons themselves with slanderous lies”. Like his compatriot Sir John Prise of Brecon, Llwyd not only cited numerous classical sources but stressed the importance of sources in Welsh, which Vergil could not read.

The Cronica Walliae also took the truth of British history for granted. The work drew heavily on the medieval Welsh chronicles known as Brut y Tywysogyon (“The Chronicle of the Princes”), which were designed as continuations of Geoffrey’s history, though Llwyd also used other sources and imposed his own shape on the whole. In particular, he divided the history by the reigns of the kings and princes whose deeds he related, from Cadwaladr the Blessed in the late seventh century to the failed revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn in 1294–5. This allowed Llwyd to present the history of medieval Wales as an unbroken succession of legitimate rulers. It also allowed him to insert the first account of Prince Madog’s alleged discovery of America in the 12th century.

<!– Below is The Conversation's page counter tag. Please DO NOT REMOVE. –>

![]()

His final sentence made clear, however, that a separate Welsh history was long over: after 1295 “there was nothinge done in Wales worthy memory, but that is to bee redde in the Englishe Chronicle”. Nevertheless, by commemorating their ancient and medieval history, Llwyd insisted that the Welsh could boast a unique pedigree and status as “the genuine Britons” in the Tudor realm.

Huw Pryce, Professor of Welsh History, Bangor University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.