State Library of New South Whales, CC BY-ND

Rachel Franks, University of Newcastle

Women have always been central to true crime stories: as victims, perpetrators, readers, and (increasingly) as tellers of these tales. Indeed, these tales, often dismissed as sensationalised violence, offer important opportunities to reflect on crime and crime control.

Many true crime writers today – including numerous women, working in a once male-dominated market – have been biographers, coroners, detectives, historians, journalists, lawyers, and psychologists. These backgrounds bring a style of storytelling that educates us about, not just merely entertains us with, crime. Importantly, many privilege complex and nuanced storytelling over simplistic stereotypes of women as just “bad” or just “good”.

Call number: DL F8/50, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, CC BY

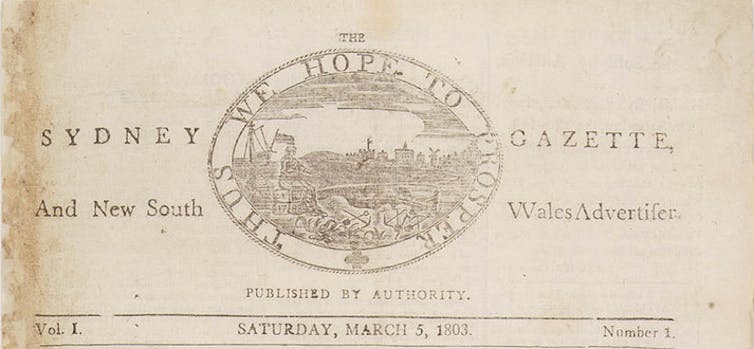

The first Australian true crime stories were transmitted orally, jotted down in journals, and entered into official records. George Howe, editor of our first newspaper, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, enthusiastically embraced the topic of crime: the paper’s first issue in 1803 included stories of fraud, attempted murder, and the brutal rape of 17-year-old Rose Bean.

The first Australian publication dedicated to true crime is Michael Howe: The Last and the Worst of the Bushrangers of Van Diemen’s Land (1818), by T.E. Wells. This short work is also the story of Howe’s companion, then victim, Mary Cockerill a young Indigenous woman. Cockerill supported Howe in a landscape forbidding and wild to the European settlers. After being betrayed by Howe – he shot her as they were being pursued, facilitating his own escape – Cockerill then used her knowledge of the bush to help authorities. Howe was captured and killed in 1818, bringing his bushranging career to an end.

In the colonial era, a woman’s status as a victim was upheld, or denied, based on her character and her ability to conform to social mores of the time. Today, women are often still judged by what they say and what they wear; their education and their occupation. How many sexual partners have they had? Are they too emotional? Are they not emotional enough? Likewise, some perpetrators have been seen as more heinous because they are women.

Women as perpetrators

In Captain Thunderbolt & His Lady (2011), Carol Baxter skilfully tells the story of Frederick Ward (“Captain Thunderbolt”), a bushranger in the mid-1800s, and his Indigenous partner-in-crime Mary Ann Bugg (“Mrs Thunderbolt”). Bugg – an intelligent, gutsy, trouser-wearing woman – is brought vividly to life, as she breaks the law and defies the feminine expectations of her time.

As Baxter notes, Bugg was dissatisfied with the social status quo, and, like many bushrangers, she received support and sympathy from the wider population. She was not all “bad” but not all “good” either. Indeed, some suggested Mrs Thunderbolt was merely blamed for the deeds of her husband. Bugg outlived her outlaw partner by 35 years, dying in obscurity in Mudgee in 1905.

One of the more dramatic true crime tales of the late colonial period, is the story of Louisa Collins. Caroline Overington looks at the life, and death, of Collins in Last Woman Hanged (2014). Accused of murder, Collins famously endured four trials in 1888, which, as Overington argues, were effectively trials of all Australian women. If women wanted equal rights, including the right to vote, “then, such equality had to be universal: women, too, would hang for murder”. In the first three trials, the juries failed to deliver a verdict. In the fourth trial, the jury found her guilty and Collins was hanged in 1889.

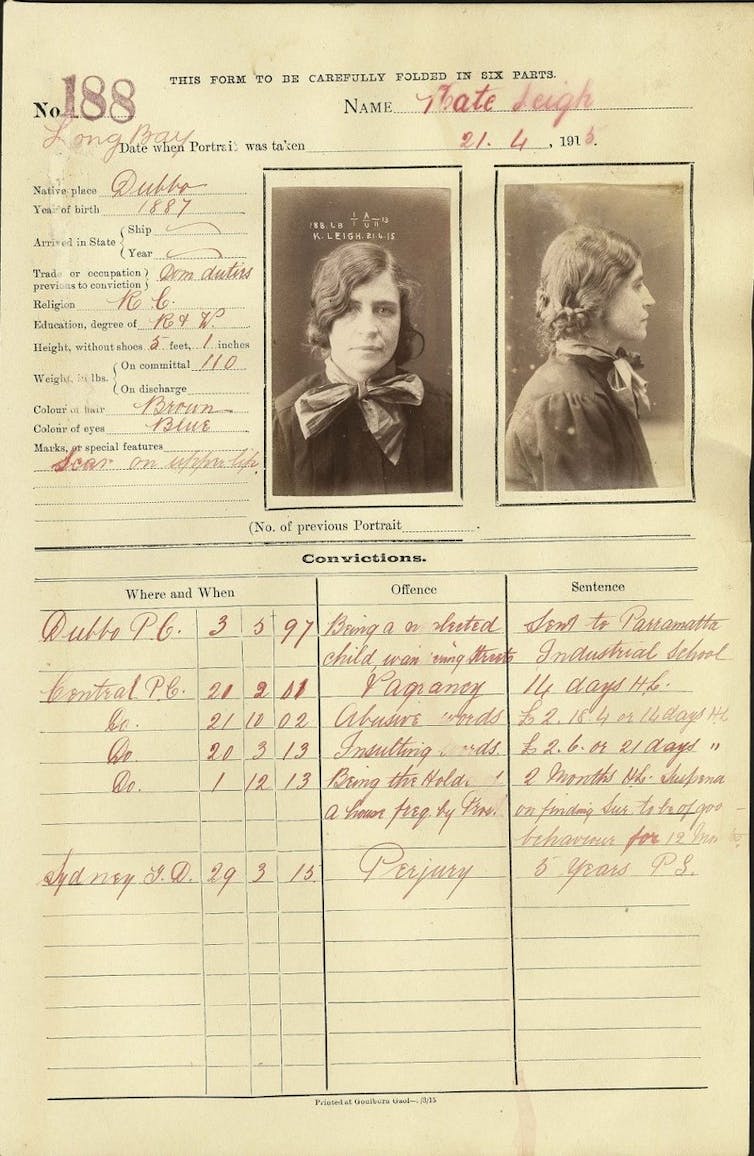

State Archives of New South Wales, CC BY

The Worst Woman in Sydney (2016) by Leigh Straw documents the life of Kate Leigh, born Kathleen Beahan, an icon of Sydney’s underworld from the 1920s through to the 1950s. A “famed brothel madam, sly-grog seller and drug dealer”, she is best known for her involvement in the “Razor Wars” when Sydney gangs used razors instead of guns. Leigh could handle a rifle (or any other weapon) and was “an intelligent criminal entrepreneur” who quickly capitalised on opportunities as they emerged. A hardened crook (who was in and out of prison), Leigh was also very generous; her Christmas parties for poor children, in Surry Hills, were legendary for the food and presents given out.

In Nice Girl (2011), Rachael Jane Chin looks at the many dreadful secrets kept by Keli Lane. Found guilty of murder and of lying under oath, Lane’s case is one that is still difficult to believe. Gender, and gendered ideals, stand out within it. Chin unpacks how Lane was a solid, middle-class young woman. She had her boyfriends but was not promiscuous. She was a teacher and had worked hard to become an elite athlete.

But underneath Lane’s “good upbringing and clean-cut appearance”, which earned her the benefit of the doubt from those around her, were five secret pregnancies during the 1990s. Two pregnancies were terminated, two infants were put up for adoption and one baby, Tegan, was murdered. Lane is serving her prison sentence, the crimes she committed as shocking now as when they were discovered. She will be eligible for parole in 2023.

Women as victims

In 1921 the body of 12-year-old schoolgirl Alma Tirtschke was found in an inner-Melbourne alleyway. Colin Campbell Ross was charged with rape and murder, as described in Kevin Morgan’s Gun Alley (2005, updated 2012). We learn the victim, just a child, was quiet but also clever and creative. As readers, we cannot help but speculate who Tirtschke could have grown up to be.

Ross was hanged in 1922: a result of false allegations, a flawed investigation, and a trial held in the press and in the courtroom. He received a posthumous pardon in 2008. This case is particularly important in the history of Australian true crime writing because, as Tom Roberts explains, it highlights the commercialisation of crime, focusing on the headline of the defenceless female, and media-driven moral panics.

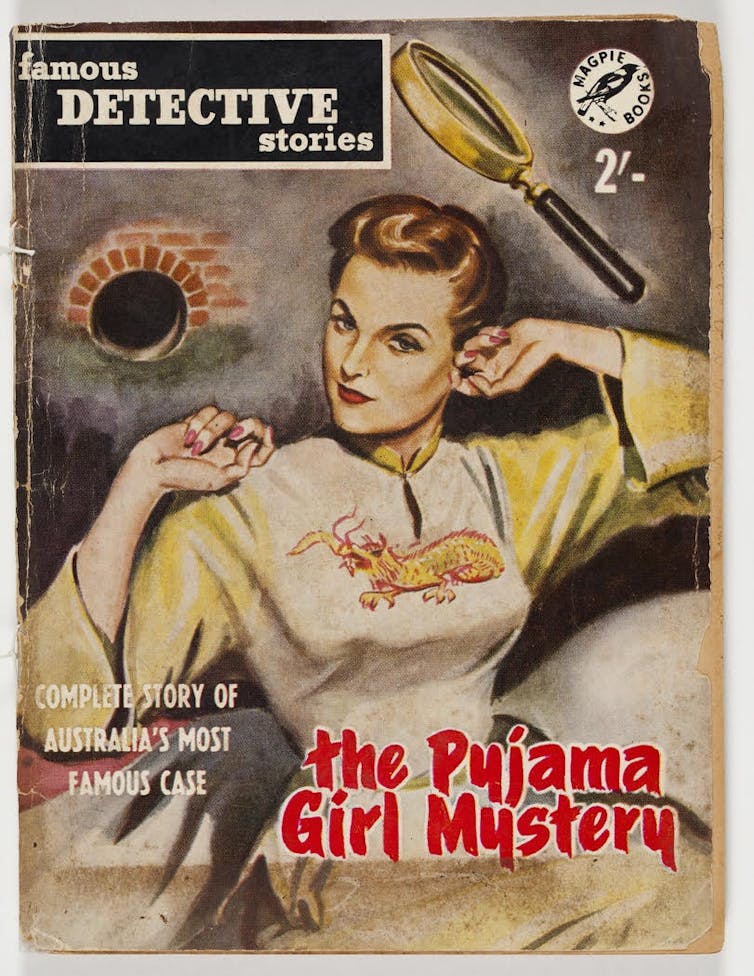

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

One of Australia’s most famous crimes is the “Pyjama Girl Case”. In 1934 the remains of Linda Agostini, born Florence Platt, was found. She had been shot, beaten, and burnt. Most notably, Agostini was wearing yellow, silk pyjamas, patterned with a dragon: a flamboyant garment in Depression-era Australia. Agostini’s body was placed on public display in an attempt by the police to discover the name of the murdered woman but it took 10 years to identify the victim. In the 1940s and 1950s, Frank Johnson published his Famous Detective Stories series, which included The Pyjama Girl Mystery. Like many of Johnson’s true crime storytelling efforts, the woman at the centre of the criminal case is presented as a sexual object.

The story of Anita Cobby, born Anita Lynch, has been told many times. The first major telling of the brutal rape and murder of the 26-year-old in 1986, is Julia Sheppard’s Someone Else’s Daughter (1991). Sheppard contrasts Cobby and her numerous contributions to the community, as a charity worker as well as a nurse, with the senseless cruelty of the men who took Cobby’s life. Stories like this one, which have stayed in the public imagination over decades, highlight how the impacts of crime extend beyond the victim, family, and friends. They also show how women can be victims of completely random acts of violence.

Many women are victims of domestic violence. The murder of Lisa Harnum, by her fiancé Simon Gittany, is described by Amy Dale in The Fall (2014). Gittany threw Harnum to her death from their apartment balcony, situated on the 15th floor of an inner-Sydney building in 2011. This is a story of control, surveillance, and toxicity. Harnum was trapped in an untenable position: too frightened to leave but also too frightened to stay. When she did try to escape, the result was tragic. Gittany was sentenced to 26 years in prison, with a non-parole period of 18 years.

Changing true crime narratives

The once “either/or” binary of “bad/good” women has given way to demands from readers to see women as complex figures within these works. As a result, more and more writers are now increasingly focussed on the human cost of crime.

Kerry Greenwood, known for crime fiction and true crime, has curated two important volumes On Murder (2000) and On Murder II (2002). Rachael Weaver, in The Criminal of the Century (2006), offers a rigorous exploration of colonial serial killer Frederick Deeming. More recently Alecia Simmonds has written on the terrible consequences seen when drug use, violence, masculinity, and psychosis collide in Wildman: The True Story of a Police Killing, Mental Illness and the Law (2015). A dominant force on the landscape of true crime writing is Helen Garner with several compelling works including Joe Cinque’s Consolation (2004) and This House of Grief: The Story of a Murder Trial (2014).

Women are also telling their own stories, as seen in Lindy Chamberlain’s work Through My Eyes (1990). Chamberlain was falsely imprisoned for the murder of her baby daughter, Azaria, at Uluru in 1980. This book delivers a very personal account of one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in Australian history.

![]() Crime is never without context and is never straightforward. Many writers – women and men – know that simplifying these stories with stereotypes, female or male, is just not good enough: for the innocent, for the guilty, or for readers.

Crime is never without context and is never straightforward. Many writers – women and men – know that simplifying these stories with stereotypes, female or male, is just not good enough: for the innocent, for the guilty, or for readers.

Rachel Franks, Conjoint Fellow, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.