The link below is to a poem by Ellen Bass – ‘Grizzly.’

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/grizzly/

The link below is to an article that gives some advice on reading poetry.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/04/16/why-to-read-poetry/

The link below is to an article that looks at whether reading poetry in the morning helps your health or not.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2020/04/10/poetry-and-health/

The link below is to an article that reports on the shortlist for the 2020 Griffin Poetry Prize.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/heres-the-international-shortlist-for-the-griffin-poetry-prize/

Andrew McMillan, Manchester Metropolitan University

One of the things you get asked most when people find out that you’re a poet is whether you can recommend something that could be read at an upcoming wedding, or if you know something that might be suitable for a funeral. For most people, these occasions – as well as their schooldays – are the only times they encounter poetry.

That feeds into this sense that poetry is something formal, something which might stand to attention in the corner of the room, that it’s something to be studied or something to “solve” rather than something to be lounged with on the sofa. Of course, this needn’t be true.

We’ve seen over the past couple of months how important poetry can be to people. It’s forming a response in advertisements and marketing campaigns, it’s becoming a regular part of the public’s honouring of frontline heroes and, for people who write poetry more often, it’s becoming a way to create a living historical document of these unprecedented times – this latter point was the aim of the new Write where we are Now project, spearheaded by poet Carol Ann Duffy and Manchester Metropolitan University.

In years to come, alongside medical records and political reporting, historians and classes of schoolchildren will look to art and poetry to find out what life was like on a day-to-day basis – what things seemed important, what things worried people, how the world looked and felt and was experienced. Write where we are Now will, hopefully, be one such resource, with poets from all over the world contributing new work directly about the Coronavirus pandemic or about the personal situations they find themselves in right now.

So the crisis has perhaps brought poetry – with its ability to make the abstract more concrete, its ability to distil and clarify, its ability to reflect the surreal and strange world we now find ourselves in – back to the fore.

Many of you might be thinking now is the time to try and get to grips with poetry, maybe for the first time. A novel might feel too taxing, watching another film just involves staring at another screen for longer, but a poem can offer a brief window into a different world, or simply help to sustain you in this one.

If you’re nervous around poetry or are scared it might not be for you, I wanted to offer up some tips.

1. You don’t have to like it

Poetry is often taught in very strange ways: you’re given a poem and told that it’s good – and that if you don’t think it’s good then you haven’t understood it, and you should read it again until you have, and then you’ll like it. This is nonsense. There are poets and poems for every taste. If you don’t like something, fine. Move on. Find another poet. Anthologies are great for this, and a good place to start with your poetry journey.

2. Read it aloud

Poetry lives on the air and not on the page, read it aloud to yourself as you walk around the house, you’ll get a better understanding of it, you’ll feel the rhythms of the language move you in different ways – even if you’re not quite sure what’s going on.

3. Don’t try and solve it

This is something else that goes back to our educational encounters with poetry – poems are not riddles that need solving. Some poems will speak to you very plainly. Some poems will simply move you through their language. Some poems will baffle you but, like an intriguing stranger, you’ll want to step closer to them. Poems aren’t a problem to be wrestled with – mostly poems are showing you one small thing as a way of talking about something bigger. Poems aren’t a broken pane of glass that you need to painstakingly reassemble. They’re a window, asking you to look out, trying to show you something.

4. Write your own

The best way to understand poetry is to write your own. The way you speak, the street you live on, the life you’ve lived, is as worthy of poetry as anything else. Once you begin to explore your own writing, you’ll be able to read and understand other people’s poems much better.

Read more:

Eavan Boland: the great Dublin poet and powerful feminist voice

I would say this as a poet, but poetry is going to be even more central to how we rebuild after this current crisis. Poetry, especially the teaching of how we might write it, has this wonderful ability to create a new language, to imagine new ways of seeing things, to help people to articulate what it is that they’ve just been through. The way we move forward, as a community, as a society and, in fact, as a civilisation, is to push language to new frontiers, to use language to memorialise, reimagine and rebuild, but also to remember that poetry can be an escape, something to be enjoyed, something to cherish.

With that in mind here is a poem I wrote for Write where we are Now.![]()

Andrew McMillan, Senior Lecturer, Department of English, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Adam Piette, University of Sheffield

The death of poet Eavan Boland comes as a soft shock to my sense of the world. The creative connections she forged between her richly various poetry, Irish culture and the fierce determinations of feminism were mesmerising. Just as important was her faith in poems as places to think and feel in, where those connections could be offered as intricate gifts to all readers.

She is rightly celebrated for her breakthrough collection, the 1980 In Her Own Image, which pitted itself against the lazy assumptions of a male-dominated poetry world and voiced the bitter extremes of female experience, like the anorexic’s fanaticism (“Flesh is heretic./ My body is a witch. / I am burning it”), the beaten wife’s survivalist plural selving (“I was not myself, myself”), the menstrual visionary (“I leash to her {the moon}, / a sea, / a washy heave, / a tide”), the crazy poetics of the kitchen (“the tropic of the dryer tumbling clothes. / The round lunar window of the washer”).

Such poems gave centre stage to female experiences and had a huge impact on the Irish poetry scene in particular, which had taken its time responding to the feminist revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.

Their accurate representation of the marginalisation of women in history and by history (“still no page / scores the low music / of our outrage” It’s a Woman’s World, 1982) was belied by the poems as public and historical voices. A feminist collection, In Her Own Image showed the world that Boland’s was a powerful voice above all and a real challenge to the Yeatsian tradition of male poetics in Ireland.

The wonderful Mise Eire (1987), meaning “I am Ireland”, for instance, takes on the identity of the many emigrant women travelling from Ireland to the New World, and opens:

I won’t go back to it

my nation displaced

into old dactyls

and the poem is colourfully detailed about the historical record, as routines being played by Boland:

I am the woman –

a sloven’s mix

of silk at the wrists,

a sort of dove-strut

in the precincts of the garrison

The ancestral women whose being she inherits through her matriarchal line and her Irish identity, women under the control of the old dispensation, the women of Irish patriarchal history, molls to the men of power – that is what she won’t go back to. So what reads as a rich imagining of the emigrant glad to be leaving is also Boland’s coded challenge to the Irish lyric tradition with its old dactyls and assumptions about women poets as strutting doves; as well as a specific historical voicing of second-wave feminism – we are not going back to that old world.

On the back of the extraordinarily febrile mind at work on her own culture and in concert with the feminism of her times, she built up a repertoire of voices that constitute some of the finest poetry in English.

Navigating between work in America and a full life in Ireland, she lived out that emigrant dream and made it real, made it her world. Her poems are intimately connected to the dailiness of her own life, to a sense of significances and exfoliations in the ordinary events in her patch of space and time. Equally, she writes poems of extraordinary power and complexity about the history of Ireland, about the Famine, the Troubles (the three-decade conflict between nationalists and unionists), about the acts of violence suffered by her people over time.

She was unafraid to make poetry do the work that once was most resolutely its task: the work of elegy, epic (her lyrics attend to history with the eye of an epic poet), lyric most of all and testimonial witnessing of experience with heart and mind.

For me, one of her tasks was to be the poet of Dublin, the Dublin she loved and cherished, and fought for and against too. Many of her very best poems bring that fabled city to new light. Her poem Anna Liffey (1997), which tussles with James Joyce’s representation of the female principle Anna Livia Plurabelle in Finnegans Wake, is also a hymn of praise to Dublin’s river Liffey:

It rises in rush and ling heather and

Black peat and bracken and strengthens

To claim the city it narrated.

Again, subtly, it is a woman’s story-telling (Anna Liffey narrating) that lays claim to this new post-feminist Dublin. Born abroad, she adopted Dublin as an émigré Irish returnee – but that journey home was also this complex act of kinship and claim:

It has taken me

All my strength to do this.

Becoming a figure in a poem.

Usurping a name and a theme.

Thank goodness for her usurpation! Such a harvest of gifts, as well.

In the incomparably beautiful And Soul (2007), Dublin’s rain is praised at the same time as Boland is battling the cloudburst of her grief for her dying mother. In The Lost Land (1998), her daughters growing up and living faraway reprise her whole life story (“memory itself / has become an emigrant”). Nobody has written so fully and well about the intimate relationship between Ireland and the United States. Ireland has lost its most exquisite chronicler:

In the end

everything that burdened and distinguished me

will be lost in this:

I was a voice.

Adam Piette, Professor of Modern Literature, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

James McGonigal, University of Glasgow

Grey over Riddrie the clouds piled up,

dragged their rain through the cemetery trees.

The gates shone cold. Wind rose

flaring the hissing leaves, the branches

swung, heavy, across the lamps.

From King Billy (1963)

Why do we remember particular poems and poets – and happily forget others? The Scottish poet Edwin Morgan was born 100 years ago, and this week marks the the start of a year of celebration of the man and his work. It goes ahead in a virtual way, with public events cancelled in days of lockdown or deferred to 2021 – an advantage of a year-long celebration.

Born in Glasgow on April 27, 1920, Edwin George Morgan led a remarkable and wide-ranging creative life. He published 25 collections of his own poetry and translated hundreds of Russian, Hungarian, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French and German poems too. He also wrote plays, opera libretti, radio broadcasts, journalism, book and drama reviews and literary criticism.

His work continues to be published, produced, taught and celebrated. His poetry is memorable not only for Glasgow, his native city, and for Scotland – but for a wider audience thanks to Morgan’s lifelong concern with universal and cosmic matters.

Morgan loved the city of his birth for its energy, industrial inventiveness, humour and crowded streets. He warmed to its humanity, shared its sorrows, wrote against scarring deprivation, recovered its history (real and imagined), and projected several Glasgows into the future.

He celebrated its changing cityscape in The Starlings in George Square, and its interactive street culture in Trio, where we encounter three Glaswegians bearing Christmas gifts of a guitar festooned with mistletoe, a new baby and a chihuahua, cosy in a tartan coat. He recorded the darker elements of Glasgow too, such as the city’s sectarian violence and notorious tribal gang culture in King Billy.

The directness of these interactions is carried in authentic urban speech rhythms new to Scottish poetry at the time. In the Snack-bar and Death in Duke Street vividly describe the long deprivation and the sudden death that are also part of the scene:

Only the hungry ambulance

howls for him through the staring squares.

Morgan taught English at Glasgow University all his working life, and became the city’s first poet laureate in 1999. He became Scotland’s laureate too, in 2004 – its first “makar” or national poet. He celebrated Scotland’s varied landscapes, people and places, whether humorously in Canedolia, or reflectively in Sonnets from Scotland.

For Morgan, part of a poet’s job was to remind Scots that if they want to achieve something in the world and to really be taken seriously, then they need to find words to show the world what they stand for. Poets and other writers can help them to do this. When Scotland’s ambitious new parliament building opened at Holyrood at the foot of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, he wrote:

What do the people want of the place? They want it to be filled with thinking

persons as open and adventurous as its architecture.

A nest of fearties is what they do not want.

A symposium of procrastinators is what they do not want.

A phalanx of forelock-tuggers is what they do not want.

And perhaps above all the droopy mantra of “it wizny me” is what they do not want.

Lines from For the Opening of the Scottish Parliament, October 9 2004

Morgan travelled widely – to Africa and the Middle East during the second world war, to Russia and Eastern Europe during the Cold War, to the US, New Zealand and the North Pole. These are the places he writes of in his poetry. The New Divan is his mysterious war poem in which he records in 100 sharp filmic stanzas, memories from the second world war desert campaign that shift like characters in an Arabian Nights tale – and yet are modern soldiers and lovers too.

Space and time travel fascinated him. A supersonic flight by Concorde to Lapland was the nearest he could actually get to outer space, where he had often journeyed in his imagination. The First Men on Mercury dramatises a linguistic encounter between Western astronauts and Mercurian beings that ends in a complete and hilarious transposition of language and power. Morgan believed that humanity would ultimately endeavour to create “A Home in Space”, which is the title of another poem that follows “a band of tranquil defiers” who decide to cut off all connection with the Earth.

This was a poet who could speak as a space module or a Mercurian, and also as an apple, a computer, an Egyptian mummy. He was an acrobat of words and identities. Perhaps his own identity as a gay man, risking censure or imprisonment through most of his life, encouraged that ability to shape-shift. His love poems are haunting. Some deal with loss or transience, as in One Cigarette, or Absence, or Dear man, my love goes out in waves, or with the physical risks of a forbidden lifestyle, as in Glasgow Green or Christmas Eve, which tells of a fleeting encounter with another man on a bus.

But his poems also celebrate ways in which all lovers share the tender details of everyday life together, as in Strawberries. His writing of gay and queer experience had a significant impact on social attitudes and political change in Scotland. His voice spoke for many young or isolated gay people, with an advocacy that was subtle but powerful in effect.

Morgan was an individualist, in some senses a loner. And yet he was also an inspirer of creative partnerships – in art, photography, opera, music and drama, cultural journalism and poetry in performance. His early support was invaluable to an array of groundbreaking poets and artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay, Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and Jackie Kay, and he enjoyed collaborations with Scots musicians such as jazz saxophonist Tommy Smith and indie band Idlewild.

Such lists could be extended. They continue to grow through the Edwin Morgan Trust, set up to administer his cultural legacy by supporting new poets and poetry in Scotland and Europe as well as wider artistic responses to Morgan’s work. There are centenary publications too with new collections of selected poems and prose. For those who loved this quiet man of Scottish poetry it promises to be a memorable year.![]()

James McGonigal, Emeritus Professor of English in Education, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Julia M. Wright, Dalhousie University

War has been widely used — and criticized — as a metaphor for dealing with COVID-19. But the metaphor didn’t come out of nowhere. Writers have long linked war and disease, and not only because war often contributes to the spread of disease.

In my study of British and Irish literature from around 1800, including writing about medicine, it’s clear that people struggled to understand disease without having evidence of bacteria or viruses. In a chapter on “Contagion” in his 1797 handbook on medicine, the physician Thomas Trotter even laughed at the suggestion that diseases were spread by “little animals.”

Yet the idea persisted. In 1828, cartoon satirist William Heath imagined river water as “Monster Soup.” In 1854, English physician John Snow used what we might now call contact tracing to show that a London water pump was at the centre of a cholera outbreak. The same year, Italian physician Filippo Pacini used a microscope to identify the cause of the disease.

Writers were aware of public and research interests in medicine and drew on them, as in the familiar example of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1818. Writers also used medical metaphors: for instance, William Blake called the influence of Greek and Latin literature a “general malady and infection.”

These writers are using figures of speech to link concepts together: war is like a storm, disease is like war, and disease is like a storm, spread through clouds of bad air, raining contagion.

Read more:

Apocalyptic fiction helps us deal with the anxiety of the coronavirus pandemic

Metaphors aren’t simply decorative. They help explain unfamiliar ideas, and help us remember them by making them vivid or surprising. When Shakespeare had Hamlet talk about picking up weapons to fight “a sea of troubles,” he was communicating a sense of overwhelming odds. The metaphor was good enough to stick and is still widely used. Metaphors can also pass judgement, like Blake associating Greek and Latin literature with disease because it promoted war.

War was almost constant for Britain at this time, and writers often turned to thunderstorms to capture the terrible sound of battles. Blake’s 1793 poem about the American Revolutionary War describes the new United States as “darkned” by storm clouds while “Children take shelter from the lightnings” and leaders speak “in thunders.” A few years later, in his poem “Fears in Solitude,” Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote about “Invasion, and the thunder and the shout.”

Medical writers of the era thought that bad air carried disease because they didn’t have the technology to see further. But they were able to connect the spread of disease with soldiers and ships. This made it an easy step from disease to war — with weather still in the mix.

In “Fears in Solitude,” Coleridge associated British imperialism with a spreading infection, carrying “to distant tribes slavery and pangs” “Like a cloud that travels on, / Steamed up from Cairo’s swamps of pestilence.” In “Adonais,” P.B. Shelley wrote of “vultures to the conqueror’s banner true … whose wings rain contagion.”

Two hundred years ago, disease wasn’t an “Invisible Enemy” or a “little animal”. It had power to kill, much like the kings who sent armies around the globe.

In her influential 1792 essay, Vindication of the Rights of Woman, English writer Mary Wollstonecraft wrote that “despots” are the source of a “baneful lurking gangrene” and lead to “contagion.” A quarter of a century later, the cholera pandemics began.

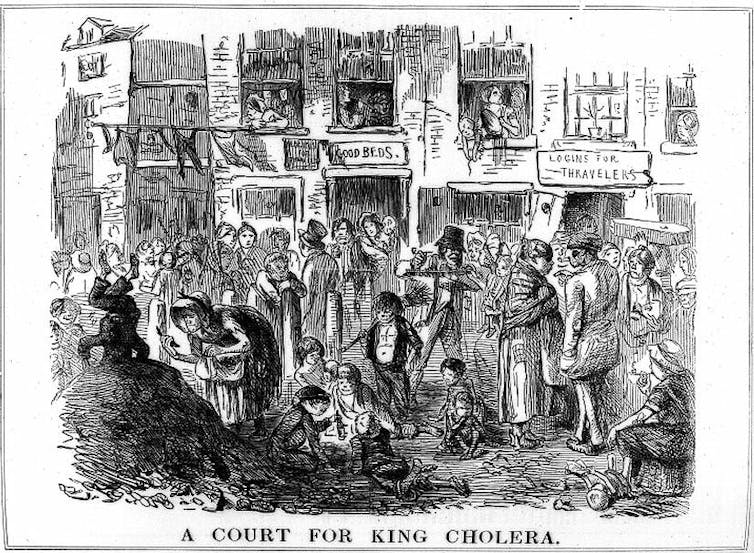

In John and Michael Banim’s 1831 poem “The Chaunt of the Cholera,” cholera doesn’t just “Breathe out the breath which maketh / A pest-house of the place.” It is a mercenary working for Europe’s monarchs: “Kings!–tell me my commission, / As from land to land I go.” Others, like English cartoonist John Leech, called the disease Lord Cholera or King Cholera.

John Leech’s 1852 cartoon, “A Court for King Cholera,” relayed a message we’re hearing now: inequality feeds pandemics. The 1853 poem “King Cholera’s Procession” also details the unsanitary conditions of the urban poor while condemning “Those that rule” for being King Cholera’s “friends.”

In her 1826 novel about a devastating pandemic, The Last Man, Mary Shelley also links rulers, war, and disease. The plague “shot her unerring shafts over the earth,” a shower of arrows, and becomes “Queen of the World.” Shelley idealizes the leader “full of care” who doesn’t want victory — only “bloodless peace.”

To these writers, war was a metaphor for the problem, not the solution.

In our time, business media suggest “battle metaphors” are overused. We have television shows like Robot Wars and Storage Wars, training sessions called “bootcamps” and elections in “battleground states.”

War is all too real and devastating in many parts of our world. But as a metaphor it is worn out — perhaps no longer vivid, no longer explanatory. Writers such as Coleridge, the Shelleys, and Blake may have seen close connections between war and disease, but their work also hints at another possibility.

Instead of talking about a war on COVID-19, let’s consider those storm metaphors. We need to stay inside and wait for it to pass.

And, while we are, perhaps we can also look to the past for help in understanding our present. Before they had evidence of germs, they could see that war and inequality spread disease.![]()

Julia M. Wright, University Research Professor, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sally Bushell, Lancaster University

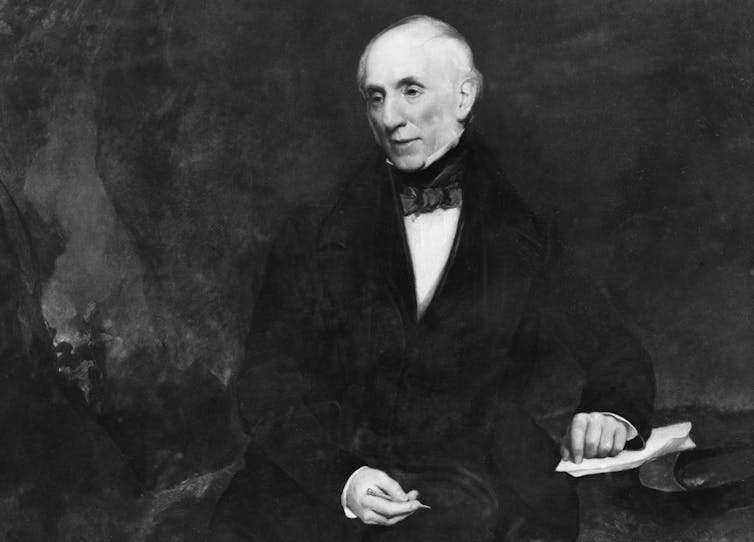

It is 250 years since the birth of the great English poet William Wordsworth. A lover of nature, his poetry abounds with images of lambs, flowers in full bloom, windswept crags and woodland scenes. His pleasure in nature, particularly that of his home the Lake District, is famous.

His contemporary Samuel Taylor Coleridge once describes his genius as “not a spirit that descended to him through the air; it sprang out of the ground like a flower.” Wordsworth did find much inspiration in the natural landscape that he would revel in on his long walks. In these house-bound times and on this anniversary, we can all find inspiration in the great poet and his love of walking as we take our daily exercise.

In a comic article from 1839 entitled Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets: “Mr Wordsworth”, the writer Thomas De Quincey criticised Wordsworth’s unshapely legs while also noting that:

[He calculated], upon good data, that with these identical legs Wordsworth must have traversed a distance of 175,000 to 180,000 English miles

In his summer vacation from Cambridge University in 1790, he walked right across revolutionary France, over the Alps and back through Germany (arriving late for the start of term). Wordsworth was still able to ascend Helvellyn, one of the highest peaks in the Lake District, aged 70 – a feat celebrated in Benjamin Robert Haydon’s portrait of him in 1842.

Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy were not only interested in large-scale walking tours but walked almost every day, at all times of the day. Dorothy’s famous Grasmere Journal, documents their walks and is itself a wonderful example of nature writing. In it she logs the minute details they would see on their walks, like daffodils near the Lake District’s Gowbarrow Park:

I never saw daffodils so beautiful. They grew about the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the lake.

Walking was not just for pleasure, though. We know that Wordsworth frequently walked to write. Dorothy’s Journal describes how:

Though the length of his walk maybe sometimes a quarter or half a mile, he is as fast bound within the chosen limits as if by prison walls. He generally composes his verses out of doors, and while he is so engaged he seldom knows how the time slips away, or hardly whether it is rain or fair.

In a poem entitled When first I Journey’d Hither to his brother John, who was away at sea, Wordsworth writes of the joy of finding a path carved into the earth by him:

With a sense

Of lively joy did I behold this path

Beneath the fir-trees, for at once I knew

That by my Brother’s steps it had been trac’d.

My thoughts were pleas’d within me to perceive

That hither he had brought a finer eye,

A heart more wakeful: that more loth to part

From place so lovely he had worn the track,

Out of his own deep paths!

The poem ends by imagining John, walking up and down on the deck of his ship at sea in tune with William as he also walks up and down to write the poem on the path that John has made for him. He imagines an empathetic connection between the two constrained spaces:

Alone I tread this path, for aught I know

Timing my steps to thine

Wordsworth is known for composing in the rhythm with the pace of his walking. In his epic autobiography, The Prelude, Wordsworth describes himself doing this and sending his terrier (Pepper) ahead to warn him of others:

And when at evening on the public way

I sauntered, like a river murmuring

And talking to itself when all things else

Are still, the creature trotted on before;

Such was his custom; but whene’er he met

A passenger approaching, he would turn

To give me timely notice, and straightway,

Grateful for that admonishment, I hushed

My voice, composed my gait, and, with the air

And mien of one whose thoughts are free, advanced

To give and take a greeting that might save

My name from piteous rumours, such as wait

On men suspected to be crazed in brain

This is also a wonderful example of why walking alone can be freeing. It allows us to be alone with our thoughts and to act freely (till someone happens by that is).

So, as you undertake your permitted daily walk, remember that constraint can also be creative, the familiar walk enjoyable in its very familiarity. Enjoy the calm of nature and, like William’s brother, John, receive that calm as a “silent poet” appreciative and receptive to the simple pleasures around you.![]()

Sally Bushell, Professor of English and Creative writing, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kevin John Brophy, University of Melbourne

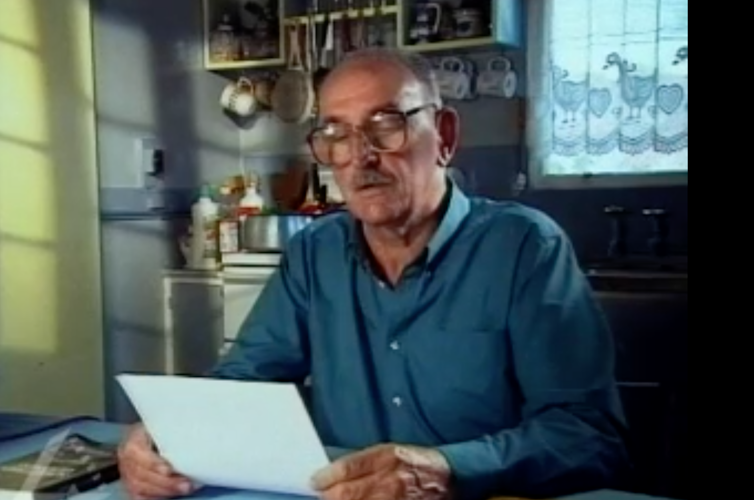

“Katrina, I had in mind a prayer, but only this came,” Bruce Dawe wrote to his infant daughter, new-born, in intensive care, her life in the balance, declaring as poets must that their poems are the best and only real gift they can give.

I did not know Dawe, who died aged 90 on Wednesday, but I knew his poetry from my first years of reading poems. For decades, the first contemporary poems many Australians read were his.

Born in 1930 in Fitzroy, a failed student after attending seven schools, he worked as a labourer like his father, a farmhand, a postman, and spent a year on the University of Melbourne campus where he became a poet and a Catholic. He joined the RAAF in 1959.

As well as publishing a growing list of books, he studied part time until he achieved a PhD. His teaching life at the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education and the University of Southern Queensland lasted from 1969 until 1993. By then he was easily Australia’s most well-read and well-loved poet. His death this week is a significant moment for poets and readers of poetry.

We know that poetry is somehow central to our nation’s soul, but mostly we like to keep its presence at the margins. In living memory, Les Murray and Dorothy Porter managed to bring poetry to wide audiences, but neither of them so broadly, neither of them prompting the passion of Dawe’s many readers.

When it comes to poetry, readers know pretty quickly what is authentic. Dawe’s poems are real enough to talk to you with one arm over your shoulder, or sit beside you, inviting you to look with them at what this whole damned creation is doing now.

But he couldn’t have survived as a poet by simply being genial. His poetry always held a deep steadiness of purpose in its gaze. This was his special skill. He was able to bring us in to seeing for instance how “the spider grief swings in his bitter geometry” (from Homecoming) when dead soldiers are freighted home.

He was uncannily capable of making poetry that talked plainly but still mysteriously about the most extreme of our experiences: funerals and suicides, drowned children, a mother-in-law’s glorious death falling out of her chair at a barbecue, the last nail being driven into the body of Christ (“the iron shocking the dumb wood”), the 1995 massacre at Srebrenica, or the hanging of Ronald Ryan.

You cannot read his poems without finding some personal connection to them too; my grandmother who once held a telegram announcing her son’s wartime death, and whose home was opposite Ronald Ryan’s bloody shootout on Sydney Road, had seemed to me to have had her life marked by images in Dawe’s poems.

In Australia, we know there’s another job requirement for any poet worth their salt, and that is a dry and thoroughly demotic wit. Dawe’s hilarious At Shagger’s Funeral is just one gem that Lawson would have been proud to have chiselled out.

New themes of gender, ethnicity, identity politics, the explosion of poetry since the avant-garde experiments of Fluxus might seem to leave Dawe’s poetry suspended in a historical moment, but this is to say no more than what happens to every strong and distinctive poet.

No one wrote poetry quite like Dawe. Lots of poets took inspiration from him too, many without realising it – the vibrant “street poetry” movement in Melbourne through the 1970s and 80s, morphing into performance poetry and spoken word – each take their impulse from Dawe’s confidence in poetry’s place as a voice for, about, and from life as it’s lived by the most desperate and the most ordinary of us.

The bravery of his poetry, its wit and sensitivity to the world are there in one of the most stark and touching love poems you could imagine reading:

Hearing the sound of your breathing as you sleep,

with the dog at your feet, his head resting

on a shoe, and the clock’s ticking

Like water dripping in a sink

– I know that, even if reincarnation were a fact,

given the inherent cruelty of the world

where beautiful things and people

are blasted apart all the day long,

I would never want to come back, knowing

I could never be this lucky twice …

(from You and Sarajevo: for Gloria)

He has been praised for the technical achievement of blending the colloquial with the lyrical, something he often got “right”. But beyond this deftness, his poems always reach towards our most humane responses to the world.

We know from our present troubles as a nation, as a planet, and as a species, that we need poets as right and true as Bruce Dawe to continue this sometimes visionary and sometimes laughably inadequate work. ![]()

Kevin John Brophy, Emeritus Professor of Creative writing, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.