Photo by John Gay © National Portrait Gallery, London

John Goodby, Sheffield Hallam University

It’s the dream of every researcher to get their hands on a hitherto-unknown manuscript by the author in whose work they specialise. As you’d imagine, most never realise that dream. But on December 9 2014 at Sotheby’s auction house in London, I was lucky enough for it to happen to me. A school exercise book that had once belonged to Dylan Thomas, filled with 16 of his poems in his handwriting, was bought by my then-employers, Swansea University, for £85,000 and given to me to edit.

A PhD student, Adrian Osbourne, was funded to help me in my labours. A greater honour, and a more daunting, more thrilling task, would have been hard for either of us to imagine.

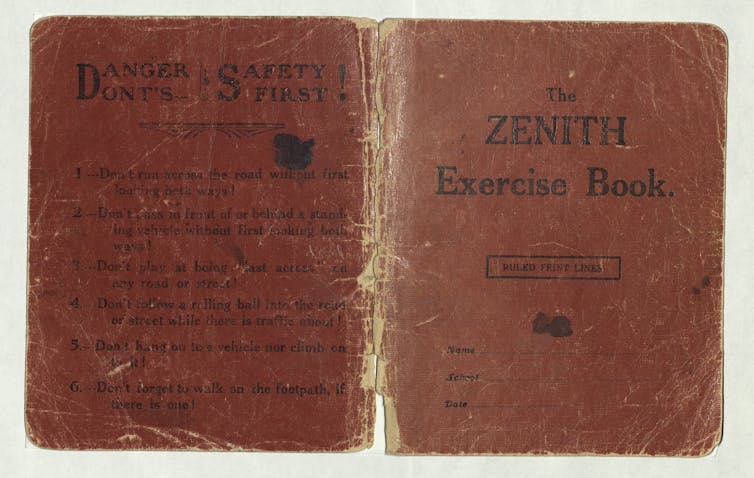

To begin at the beginning, however, some context. From April 1930, aged 15, Thomas began copying his completed poems into a series of school exercise books. In his short story, The Fight, the “D. Thomas” character notes how: “In the evening, before calling on my new friend, I sat in my bedroom by the boiler and read through my exercise-books full of poems. There were Danger Don’ts on the backs.”

Swansea University, Author provided

In a letter of 1933, Thomas referred to an “innumerable” number of such notebooks. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until 1941. At that point, in the darkest days of the second world war, hard up and with a family to support, he sold the first four, which run from April 1930 to April 1934, to the library of the State University of New York at Buffalo. Scholars were given access to them and they were published in 1967 as Poet in the Making: The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas.

No more notebooks emerged during Thomas’s lifetime, nor – despite much speculation – did any appear after his death in 1953. Thus, the Sotheby’s notebook is the only one to have appeared, and it covers the period summer 1934 to August 1935 – making it a direct continuation of the first four.

Scrap paper?

The fifth notebook’s extraordinary nature as an object is matched by the story of its survival. Two notes contained in the Tesco’s bag in which the notebook was found allowed us to establish this. The first, a brief description by Thomas himself, shows that the last time he was in possession of it was early 1938.

After marrying in summer 1937, he and Caitlin Macnamara lived with Caitlin’s mother at her home in Hampshire until early 1938. The second note – by Mrs Macnamara’s maid, Louie King – revealed that after Dylan and Caitlin’s departure she was given the notebook, with other “scrap paper” they left behind, to burn in the kitchen boiler. King, however, withheld the notebook from its fiery fate – out of curiosity, sentiment, or for some other reason we know nothing about. When she died in 1984 the notebook passed to her family, who kept it, still a secret to the outside world, until 2014.

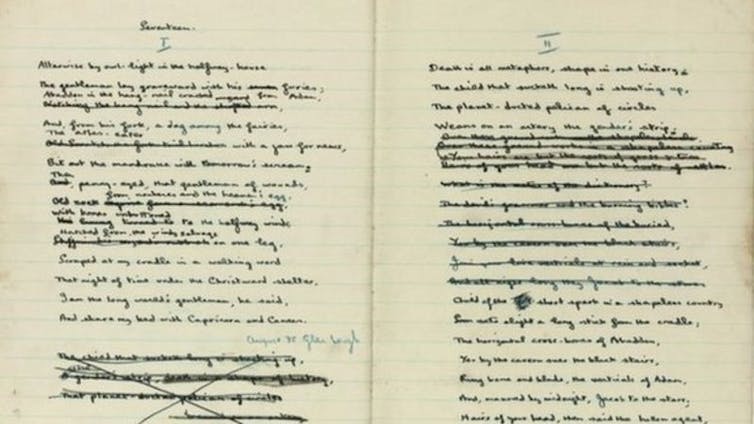

We now had three tasks – to transcribe the notebook poems, deciphering, if possible, Thomas’s many corrections and deletions. We then set out to compare them with the published versions and to work out what light – if any – they shed on Thomas’s poetic development.

It should be said that the fifth notebook poems are all published ones. Unlike its predecessors it contains no unpublished items (this may be why Thomas does not seem to have minded losing it). Where it differed was in the number of corrections it contained. The poems in the first four notebooks are almost always clean copies. In the fifth, many poems undergo radical revision, allowing us to trace Thomas’s creative processes at first hand.

Swansea University, Author provided

Luckily, we were able to realise most of our aims. Thomas’s handwriting is clear, so most poems and corrections were easy to read. Some problems arose as the notebook progressed, and the poems grew more complex and worked-over. Usually, educated guesswork (not to mention my colleague’s keen eyesight) carried us through – although in a handful of cases we called in a technician armed with a super-photocopier. In the end only five words were unresolved.

Changing style

Among the deleted passages were many of great beauty and originality, some of which Thomas reworked elsewhere. There were also three stanzas, in two of the poems, which had never been seen before.

Everywhere his incredibly rapid development as a poet was evident. Sometimes, even the tiniest item could alter our understanding of a poem; in I Dreamed My Genesis, the notebook confirmed that a comma should replace a full stop found in three print editions, making better sense of eight lines of the poem.

At the other end of the scale of significance, after poem eight, When, Like a Running Grave, we noted that Thomas had, unusually, written out the date in full: “26th October 1934” – the eve of his 20th birthday – with an emphatic line in the centre of the page. We know from the number of poems he wrote about birthdays (they include Poem on His Birthday and Poem in October) that they held great significance for Thomas. So we feel it is no coincidence that the poems that follow this point, beginning with Now and culminating in Altarwise By Owl-Light, the final poem, differ from these before it, and are the most experimental he ever wrote. Agonisingly aware of human mortality, of the end of youth, this emphatic dating marks the exact moment of Thomas’s momentous decision to adopt a more daring style.

The notebook, then, represents a kind of hinge in his early career, and this is something we could only have learned from the notebook itself, since the stylistic shift is completely obscured by the non-chronological order in which When, Like a Running Grave and Now were published. It grants us the privilege of witnessing, for the first time, the young Dylan Thomas at the height of his powers, seizing and reshaping his poetic destiny.![]()

John Goodby, Professor of Arts and Culture, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.