MCAD Library/flickr, CC BY

Randy Malamud, Georgia State University

Email has become so prevalent in our lives that I felt compelled to write about it for a Bloomsbury series called “Object Lessons” that examines “the hidden lives of ordinary things.”

Perhaps I chose this topic because I wanted to be surprised by what I would learn. Email had always evoked the image of my energy, attention and intelligence being sucked away, byte by byte, in a deadening tsunami of ill-composed blather, bland formalities and corporate groupthink. But I hoped my literary training could help me unearth some diamonds in the rough, some redeeming rhetorical force.

It turns out my chief discovery was how much richer old-fashioned letters are. An email is like a letter shorn of almost everything people liked about letters: the feel and smell of stationery, the confident authority of letterhead, the art of penmanship, the closing signature in the writer’s hand.

On paper, lives were lived, trysts arranged, manifestos mailed and wars waged; the shift from “communication” to “.com” has stripped away all of this historical and social value.

The satisfaction of a letter ‘done and signed’

Literacy rates jumped globally in tandem with the invention and expansion of mail service. People composed their letters with effort and pride, perhaps understanding that well-written correspondence wouldn’t be thrown in the trash.

The song “Letters,” from Dave Malloy’s 2012 musical “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812,” extols the joy and satisfaction of letter-writing: “We put down in writing what is happening in our minds.” Once it’s on the paper “we feel better – it’s like some kind of clarity when the letter’s done and signed.”

Email is certainly convenient. But will there ever be an electronic equivalent of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” the literary correspondence of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell or the epistolary passion between Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok?

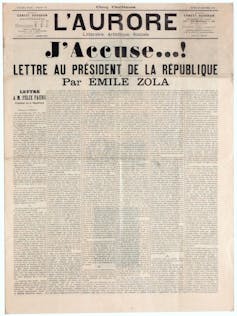

Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme

Émile Zola’s “J’Accuse!” was a letter – an open letter – to the French president, castigating the army for unlawfully jailing a Jewish officer. The letter traveled the world, inspiring others who sought to challenge those in power.

Is there such a genre as an “open email”? The only thing that comes to mind is accidentally hitting reply-all.

Letters changed storytelling: In Samuel Richardson’s 1740 epistolary adventure, “Pamela; or, Virture Rewarded,” a 16-year-old servant named Pamela Andrews details her boss’s sexual harassment in letters to her parents. Today it’s considered the first novel.

Letters spread the Gospel, with St. Paul’s Epistles disseminating early Christian teachings to the Corinthians, Romans and Thessalonians; in letters to Penthouse, they channeled erotic desire.

The value letters possess is perhaps reflected in their price.

“This boat is giant in size and fitted up like a palatial hotel,” a man named Alexander Holverson wrote from the Titanic the day before it sank. “If all goes well we will arrive in New York Wednesday AM.” His letter sold for six figures in 2017.

And after President Abraham Lincoln received a petition from children asking him to free the slaves, he responded with a letter: “Please tell these little people I am very glad their young hearts are so full of just and generous sympathy.” It brought in US$3.4 million at a 2008 auction.

Empty, ephemeral email

“There is no standard nowadays of elegant letter writing, as there used to be in our time,” grumbled a woman at the turn of the 20th century. “It is a sort of go-as-you-please development, and the result is atrocious.”

This complaint was prompted not by email but by the growing fad of sending postcards, which were popularized at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition.

Short, informal and comprised of dubiously grammatical prose, postcards, some feared, imperiled epistolary eloquence.

Sound familiar?

Still, email seems particularly reductive. Nearly 300 billion are sent each day, but I wonder if there will ever be a truly valuable email, a famous email or a celebrated email.

Even when a presidential election turned on a collection of home-brew email – tens of thousands from Hillary Clinton’s ignominious private server and another leaked batch from her campaign chair John Podesta – what information did they contain?

In one, senior Clinton Foundation official Peter Huffman writes:

“Question: why do I use a ¼ or ½ cup of stock at a time? Why can’t you just add 1 or 2 cups of stock at a time b/c the arborio rice will eventually absorb it anyway, right?”

Podesta responds (with no time to edit, possibly because he is so busy losing an election):

“Yes it with absorb the liquid, but no that’s not what you want to do. The slower add process and stirring causes the rice to give up it’s starch which gives the risotto it’s creamy consistency.”

Email is ultimately a paltry and often disappointing piece of text – grammatically challenged, disheveled and ephemeral. Often ignored or deleted, it ricochets through cyberspace in search of validation. Dealing with a cluttered inbox is a chore; emails that require a response loom.

It’s surprising how banal email is, given how intricately interwoven it is with our existence. Or maybe it’s not surprising at all. Maybe it’s just the mirror held up to life, and we are precisely as trite as our email suggests.![]()

Randy Malamud, Regents’ Professor of English, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.