Tim Luckhurst, Durham University

During the second world war, Britain’s national daily newspapers usually supported the government’s portrayal of the national war effort as flawlessly heroic. This was a just war – and supported as such even by many Britons who, until 1940, had supported pacifist organisations such as the Peace Pledge Union.

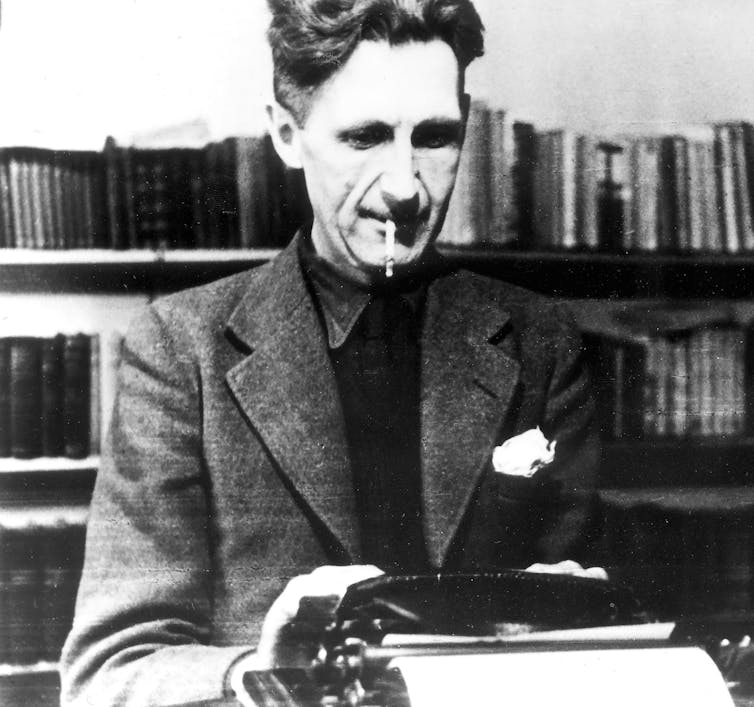

But Tribune, the weekly newspaper founded by wealthy Labour MPs Sir Stafford Cripps and George Strauss and edited by Aneurin Bevan, was bolder. Promoting itself as “Fresh and Fearless” Tribune relished controversy. In September 1943, it celebrated the recruitment of an expert controversialist as its literary editor: George Orwell.

Orwell soon seized upon a topic the wartime coalition had worked assiduously to conceal: the deliberate killing of German civilians in colossal RAF raids on German cities. His pretext was the publication by Vera Brittain, the feminist and pre-war pacifist, of Seed of Chaos, her pungent denunciation of obliteration bombing. Supporting her case with eyewitness accounts by neutral Swiss and Swedish newspaper correspondents, Brittain recounted tales of corpses “all over streets and even in the tree-tops” and women “demented after the raids, crying continuously for their lost children”.

Detecting sanctimony, Orwell attacked head on with a piece entitled “As I Please”. There was, he wrote, “something very distasteful in accepting war as an instrument and at the same time wanting to dodge responsibility for its more obviously barbarous features”.

Talk of “limiting or humanising” total war was “sheer humbug”, Orwell insisted. Warming to his theme, he condemned Brittain’s “parrot cry” against “killing women and children” and insisted: “It is probably better to kill a cross section of the population than to kill only the young men.” If allied raids had killed 1.2 million German civilians, “that loss of life has probably harmed the German race somewhat less than a corresponding loss on the Russian front”.

Tribune’s readers were not unanimous in their support for Orwell. A flow of critical letters arrived but the literary editor did not budge. He “did not feel that mere killing is all important”. There was, he suggested, a moral case for killing German civilians. It brought home the nature of modern war and might make such conflict less likely.

Hard truths

Orwell’s stance was in stark opposition to government policy. This was to pretend that civilian deaths were rare collateral damage in raids meticulously targeted at German industrial and military infrastructure. In fact, Orwell’s defence challenged the Air Ministry as directly as Brittain’s moral outrage. Orwell recognised that area bombing was intended to cause mass civilian casualties and routinely did so.

Military historian and author Martin Middlebrook describes the British government’s statements about area bombing between 1942 and 1945 as “a three-year period of deceit on the British public and world opinion”. The areas attacked were “nearly always city centres or densely populated residential areas”. Britain had invested vast resources to build a fleet of heavy, four-engine bombers among which the Avro Lancaster was king. Mass raids against cities including Cologne, Essen and Hamburg soon demonstrated that the Lancaster’s brave, vulnerable crews could not hit targets with any precision.

Air Marshall Sir Arthur Harris pleaded with the prime minister to admit that raids involved the deliberate murder of civilians. In October 1943, he wrote to Churchill’s friend, the air minister Archibald Sinclair, demanding bombing tactics be “unambiguously and publicly stated”, writing:

That aim is the destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers and the disruption of civilised community life throughout Germany.

Harris wanted ministers to tell the public that the deaths of women and children were not a “byproduct of attempts to hit factories”. Such slaughter was one of the “accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy”.

Even when the Associated Press described Allied raids on Dresden as deliberate “terror bombing”, the government continued to deploy bland euphemisms. By recognising that RAF Bomber Command killed civilians as a conscious act of policy, Orwell and Tribune were playing with fire. They were not censored or condemned because it suited ministers to tolerate dissent in small circulation weekly titles. Such robust debate burnished Britain’s democratic credentials and reassured her American allies.

The last word

Brittain was not reassured. Writer Richard Westwood has shown that she resented Orwell’s attacks so intensely that she would revisit their dispute years after his death in order to “win her argument with Orwell in retrospect and when he could not respond”. This she attempted in Testament of Experience by quoting selectively from a report Orwell sent from Germany for The Observer in April 1945.

Brittain suggests he retracted his support for obliteration bombing. In fact, Orwell described damage done by allied bombs and argued that the Allies should not impose harsh reparations. A punitive approach would leave Germans dependent on international aid. He did not apologise for the RAF’s work. Instead, he repeated his defence that “a bomb kills a cross-section of the population whereas the men killed in battle are exactly the ones the community can least afford to lose”.

Orwell’s candour about area bombing was a robust example of dissenting wartime journalism. It demonstrated Tribune’s editorial courage and that the wartime coalition understood it could not reconcile defence of democracy with suppression of free speech.

Brittain was wrong to misrepresent him. His work illustrates how intelligent publications with thoughtful readers upheld Britain’s democratic tradition in wartime. Such journalism was not restricted to the left. The Spectator and The Economist played comparable roles on this and other subjects.

Tim Luckhurst will deliver his online lecture to the Centre for Modern Conflicts and Cultures via Zoom between 4pm and 5 pm on Tuesday, June 2, 2020. To attend please register here.![]()

Tim Luckhurst, Principal of South College, Durham University. He is a newspaper historian and an academic member of the University’s Centre for Modern Conflicts and Cultures., Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.