Wikimedia Commons

Thomas McLean, University of Otago

In revealing the charms and follies of genteel English society, Jane Austen has few competitors. Yet as Britain limps towards Brexit, I can’t help wondering why there are no foreigners in her major fiction. Many thousands of continental Europeans settled in Britain after the French Revolution and during the Napoleonic wars. Couldn’t just one of the Bennet sisters have fallen in love with a charming Belgian or a wealthy German? Wouldn’t the well-travelled Frederick Wentworth of Persuasion have a dear friend from Spain or Italy?

Such questions may seem trivial, but they gain significance at a time when we expect a lot from Austen. In the past few decades, scholars have regularly turned to her novels for insights into the larger issues of her era (women’s education, slavery, war) and our own (climate change). Some even want to see her as a radical.

I’m not so convinced by this progressive – or even subversive – Austen. She was unquestionably sensitive to the epoch-defining events taking place around her. Two of her brothers were officers in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars; another was a banker who was ruined in the post-war financial crisis. Certainly, there are moments in the novels when these larger events make an appearance. How could they not?

Read more:

Jane Austen’s curious banking story makes her an apt face for the £10 note

But are such moments enough to make Austen’s works a source of great insight into the social issues of her era? In matters of love, friendship and the societal expectations of the landed gentry, Austen is always astute and entertaining. But consider all the elements of her society that Austen left out.

Are there, for instance, any Catholics in Austen’s novels? Any Jews? Mark Twain wrote that Austen’s novels made him feel like a “barkeeper” surrounded by “ultra-good Presbyterians” – but are there any actual Presbyterians in her novels? So far as I can tell, all of her principal characters are Anglican.

Are there any foreigners – a Frenchman, say, or a visiting Spaniard? Nope. Northanger Abbey mocks the English affection for gothic novels set on the continent, but no one from the continent appears in the novel. In a scene from Emma that Priti Patel might applaud, Frank Churchill rescues Harriet Smith from a group of “loud and insolent” Romany children.

How about representatives from other parts of the UK? In Austen’s novels, Scotland is mainly a place to which giddy young women elope. As for Wales, well, there’s a “Welch cow” in Emma. Ireland does a little better: in Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennet annoys her sister by playing Irish songs on the piano; and in Emma, an honest to goodness Irishman, one Mr Dixon, plays a minor role – though, like so many other male characters in Austen’s novels, he isn’t important enough to earn a first name.

Home and away

Austen is deservedly recognised for bringing greater realism to the Anglophone novel and for presenting a new psychological depth in her characters. Yet this position should not be confused with the idea that Austen somehow tells us more about Regency England than any of her contemporaries – or that her works contain all the complexities of her era if only we look closely enough. They tell us very little about the way the English looked on their British and European neighbours.

Ben Sutherland via Flickr, CC BY-SA

I hear you ask, well come now, you don’t really expect a Regency-era author to include foreigners, revolutionaries and exiles in her novel, do you? Well, yes, actually I do. Many of Austen’s forgotten contemporaries – writers like Charlotte Smith, Frances Burney, and Maria Edgeworth – did just that. Another more famous contemporary, Mary Shelley, created the era’s greatest study of an outsider ostracised by society, Frankenstein. If we imagine that Austen provides a complete picture of Regency life, these authors prove us wrong with their more international and political perspectives.

This is not to say that they are better writers than Austen. Reading Austen’s contemporaries illuminates what makes Austen a great (in many ways superior) writer. Austen is utterly in command of the order and organisation of her best narratives – every character, every encounter, every character foible is there for a well-planned purpose.

Similarly, Austen’s protagonists are true to themselves. It is rare indeed for a reader to feel that her characters act in ways that were not foreseeable from the start. Her narrators keep a respectable distance from the action of the story: they provide enough information to leave readers feeling secure, but they rarely call attention to themselves or comment at length on the unfolding action. In all of these aspects, Austen has no Regency-era peer.

Doing the continental

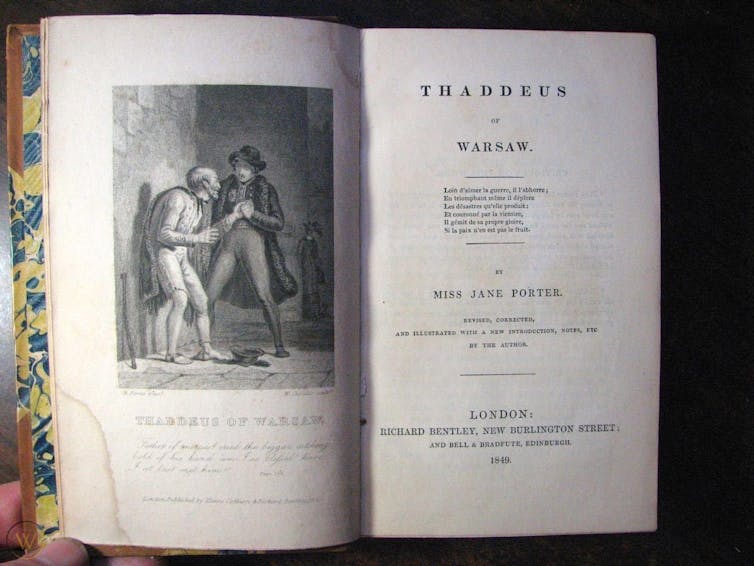

Nevertheless, some of these forgotten works illustrate the storytelling pathways that Austen never attempted. If I were to choose one work from Austen’s time that speaks most clearly to our own moment and showcases all that Jane left out, it would be Jane Porter’s novel from 1803, Thaddeus of Warsaw. Porter’s novel was a great success when it first appeared, and it remained in print for most of the 19th century.

Worthopedia

Thaddeus – an early 19th-century forerunner to Walter Scott’s Waverley and William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair – tells the story of Count Thaddeus Sobieski, who escapes to Britain after his homeland falls to Russian invaders. Penniless, he hides his identity and makes his way among the rich and poor of London, finding work where he can, and coming to the aid of those less fortunate than he. He is befriended by a group of women, who assist or punish him, according to their impulses.

Imagine a Jane Austen novel with a Polish protagonist. Imagine an Austen novel where British women welcome an immigrant into their lives. Imagine an Austen novel where a character goes looking for work.

The passages in Thaddeus that resonate the most today, however, are the commentaries by British characters who are troubled by the presence of Polish exiles, like Thaddeus, among them. One character announces, “it is our duty to befriend the unfortunate; but charity begins at home … and, you know, the people of Poland have no claims upon us”. Another declares, “Would any man be mad enough to take the meat from his children’s mouths, and throw it to a swarm of wolves just landed on the coast?” No question that these characters would have voted “Leave”.

Today there are almost one million people living in the UK who were born in Poland. No matter what happens with regard to Brexit, these people have already changed their adopted homeland. While writers like Agnieszka Dale and Wioletta Greg create a new body of Anglo-Polish literature, Thaddeus of Warsaw reminds readers of the long links between the two countries.

It also reminds us that a satisfying romance, whether it concerns Emma Woodhouse or Thaddeus Sobieski, needs to please its readers. It won’t be giving too much away to note that, at the conclusion of Thaddeus of Warsaw, the meeting of wealth and love allows for a happy ending. That was one lesson that Jane Austen taught us a long time ago.![]()

Thomas McLean, Associate Professor, English and Linguistics, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.