The link below is to an article that looks at decluttering books – yes, another one.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-goodbye-stuff-books-20170511-htmlstory.html

The link below is to an article that looks at decluttering books – yes, another one.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/books/jacketcopy/la-ca-jc-goodbye-stuff-books-20170511-htmlstory.html

The link below is to an article that takes a look at letting go of books. This all seems a little unsettling to me 🙂

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/essay/article/let-go-of-your-books/

The link below is to an article that provides 8 ideas for what to do with unwanted books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/01/10/repurpose-unwanted-books/

Dominique Boullier, Sciences Po – USPC; Mariannig Le Béchec, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and Maxime Crépel, Sciences Po – USPC

We stand amazed by the vitality of printed books, a more than 500-year-old technique, both on and offline. We have observed over the years all of the dialogue which books have created around themselves, through 150 interviews with readers, bookshops, publishers, bloggers, library assistants, 25 participant observations, 750 responses to an online questionnaire and 5,000 mapped sites in France and the francophone world. An impressive collective activity. So, yes, your book carries on living just by staying on your shelf because you talk about it, remember it, and refer to it in conversation. Even better still, you might have lent it to a friend so that she can read it, perhaps you have spent time with people who have spoken about it before buying it, or after having read it. You will have encountered official reviews, of course, and also blogs about it. The conversation goes on even when the book is no longer in circulation.

What first struck us was the very active circulation of books in print, compared with digital versions which do not spread so well. Once a book has been sold either in a bookshop or through an online platform, it has multiple lives. It can be loaned, given as a present, but also sold on second-hand, online or in specialist shops. And it can go full circle and be resold, such journeys made in a book’s life are rarely taken into account by the overall evaluation of the publication.

The application Bookcrossing allows you to follow books that we “abandon” or “set free” by chance in public places so that strangers take possession of and, then, you hope, get in touch to keep track of the book’s journey. Elsewhere, the book will be left in an open-access “book box” which have popped up across France and other countries. Some websites have become experts in selling second-hand books like Recyclivre, which uses Amazon to gain visibility.

Yard sales, antiques fairs, book markets give a new lease of life to countless books which remained forgotten because they were a quick one-time read. The book as a material object, regardless of its age, retains an unequalled sensorial pleasure, and brings with it special memories, bygone times, a sacred piece of craftsmanship with its fragile bindings, or, the nostalgia offered by children’s books or fairy tales.

Whole professions are dedicated to the web, and increasingly so, since it first came into existence. This has turned the second life of books and the recycling of them into a money-making machine for online retailers, and as a result books are kept alive. Some people have become eBay sellers, experts only thanks to the books they sell on this platform. Sometimes even, these books’ lives are extended by charity shops, such as Oxfam. At some stage however, there is only the paper left to give a book its value, once it has been battered and recycled.

One would have thought that faced with the weight, volume, and physical space occupied by books in print, that the digital book ought to have wiped the floor with its print counterpart. This has been the case with online music, for example, which practically handed a death sentence to the CD, or for films on demand which have greatly shrunk the DVD market. However, for books, this simply has not happened. In the United States like in France, the market for online books never surpasses the 20% mark of the sales revenues of books in print. And that is without including the sales revenue of the second-hand book market as we previously mentioned. The digital book seldom goes anywhere once purchased, due to controls imposed on the files by digital-rights management (DRM) and the incompatibility of their formats on other digital devices (Kindle and others).

Our interviews revealed the pleasure of giving books as presents, but also of lending them. The exchange of the physical item with its cover, size and unique smell bring much more satisfaction than if a well-meaning friend offers you digital book files on a USB stick containing… a thousand files already downloaded! Indeed, the latter will seldom ever be considered a present but rather a simple file transfer, equivalent to what we do several times a day at work. This also gives rights holders reasons to thus decry “not paying is theft”, in this case the gift of files would also become theft.

Bloggers who exchange books as presents (bookswapping) show that goodwill prevails and puts stress on the backburner. This is done on the condition that the book is personalised in some way: a poignant quote, a meaningful object associated in some way with the book (cakes for example!), and the surprise of receiving a completely random gesture of kindness.

What travels even better than books are conversations, opinions, critiques, recommendations. Some discussions are created within or around reading groups or in dedicated forums online such as the Orange Network Library, for example. There are recommended reading lists, readers’ ratings, and book signings with authors are organised. These networks are digital, but they existed well before the Internet, and they remain dynamic today.

However, the rise of blogs at the start of the 2000s led to an increase in the number of reviews by ordinary people. This provided visibility, even a reputation for some bloggers. Of course, institutional and newsworthy reviews continue to play their role in guiding the masses, and they are influential prescribers protected by publishers. But websites like Babelio, combine a popular expertise, shared and distributed among many bloggers who are sometimes very specialised themselves. The website was created in 2007 and has over 690,000 reader members.

The proliferation of content and publications can easily disorientate us; the role of these passionate bloggers, who are often experts in given literary fields, becomes important because they are “natural” influencers one might say, as they are the closest to the public. However, some publishers have understood the benefits of working with these bloggers, especially in so far as concerns specialist genres like manga, comics, crime novels or youth fiction. Sometimes a blogger, YouTuber and web writer is published like Nine Gorman.

Some bookshops contribute even more directly in coordinating these bookworms, they “mould” their audience, or at least they support the books both online and in their shops with face-to-face meetings. Conversation is a unifying force for fans who are undoubtedly the best broadcasters across a broad sphere.

Platforms encourage readers to expand their domain, in the guise of fanfictions, which are published online by the author or his readers. The relationship with authors is closer than ever and is much more direct, the same can be said of the music industry. On particular platforms like Wattpad, texts which are made available are linked with collective commentary.

But above all, the dialogue about reading has often been transformed into writing itself. It might be published on a blog and may be likened to authorial work but at the other end of the spectrum, it might be something modest like the annotations one leaves in their own book. These annotations, more common in non-fiction texts, can form a sort of trade. For example if you lend or sell on a book, which is also stocked and shared with the online systems of Hypothes.is, it allows any article found on the web to be annotated, and the comments saved independent to the display format of the article. This makes it easier to organise readers into groups.

Printed books have in fact become digital through the use of digital platforms which allow them to be circulated as an object or as conversations about the book. The collective attention paid creates a permanent and collaborative piece of work, very different to frenetic posts on social media. Readers take their time to read, a different type of engagement altogether to social media’s high frequency, rapid exchanges. The combination of these differently paced interactions can, though, encourage one just to read through alerts from social media posts then followed by a longer form of reading.

Networks formed by books constitute as well a major resource for attracting attention. This is still not a substitute for the effects of “prize season” which guides the mass readership, but which deserves to be considered more critically, given the fact that publishers increasingly take advantage of these active communities.

It would thus be possible to think of the digital book as part of the related book ecosystem, rather than treating it as just a clone. To call it homothetic, is to say that it is an exact recreation of the format and properties of the book in print in a digital format. Let’s imagine multimedia books connected to, and permanently engaged with, the dialogue surrounding the book – this would be something else entirely, affording added value which would justify the current retail price for simple files. This would therefore be an “access book” and which would perhaps attract a brand new audience and above all it would widen this collective creativity already present around books in print.

Dominique Boullier, Mariannig Le Béchec and Maxime Crépel are the authors of “The book exchange: Books’ lives and readers’ practices.”![]()

Dominique Boullier, Professeur des universités en sociologie, Sciences Po – USPC; Mariannig Le Béchec, Maître de Conférences en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and Maxime Crépel, Sociologue, ingénieur de recherche au médialab de Sciences Po, Sciences Po – USPC

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Keith Gottschalk, University of the Western Cape

Writings on South African liberation struggle icon Winnie Mandela almost all fall into one of two categories – either hagiography or demonology. These two books – Truth, Lies and Alibis. A Winnie Mandela Story, by Fred Bridgland and Sisonke Msimang’s The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela. A Biography of Survival, try to be more nuanced.

Bridgland was a correspondent for Britain’s leading right-wing newspaper, the Daily Telegraph. For years, he dispatched empathetic reports on an anti-communist hero of the cold war, Jonas Savimbi and his UNITA movement, which were at war with Angola’s ruling MPLA – an ally of the ANC.

Readers might take it for granted that anything he writes would be hostile to the ANC. So Bridgland makes a point of prefacing his book on Winnie Mandela by first placing on record that Savimbi became paranoiac, and committed massacres of entire families of his leading officials. Bridgland is currently writing up these atrocities; in effect he attempts to so show his even-handedness.

Sisonke Msimang, author of Always Another Country: A Memoir of Exile and Home, has also written articles for the New York Times, the Guardian, and Al Jazeera. She writes near the start of her biography: “I will not pretend otherwise: I am interested in redeeming Ma Winnie”.

But towards the end, she writes: “It is deeply uncomfortable to acknowledge Winnie’s involvement in Stompie’s death, and in the disappearances of Lolo Sono and Sibuniso Tshabalala, while also holding her up as a hero.

She qualifies her views further:

In a perfect world, her place is not on a pedestal… I am prepared to raise her up in the hopes that, one day, South Africans might ethically and in good conscience take her down.(p.157)

Msimang also writes in her conclusion that she’s even prepared to say give up her admiration for the complicated Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. “I cannot do so, however, without a few conditions … The past must be opened up not just to grief, but to the structural nature of racism.” She means the class exploitation coloured by colonialism and finally apartheid.

This review needs to start with three disclosures. This reviewer is a member of the African National Congress. He is also a friend of the Horst Kleinschmidt mentioned in Bridgland’s book. And he has, in the company of others, briefly met Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Zindi Mandela, and Nelson Mandela.

The issues these two biographies raise, of liberators’ wartime actions, are not unique to South Africa. For example, post-WW2 readers, with their knowledge of the holocaust of six million Jews and three million Christian Poles, also have to debate Bomber Harris’ saturation bombing of German residential downtown areas and suburbs.

In chapter two Bridgland summarises the South African police’s Special Branch’s persecution of her. The remaining 27 chapters and epilogue summarise Madikizela-Mandela’s persecution of others. The overwhelming majority of facts in his book were published two decades ago – and never refuted.

His book also flags the issue of those who lobbied the then Chief Justice Corbett about Winnie’s pending trial. This included the then Minister of Justice, Kobie Coetsee, the then head of the National Intelligence Service Neil Barnard, and the then British ambassador Robin Renwick. He evidently didn’t rebuke any of them.

Msimang’s most persuasive arguments are when she points out the sexist double-standards in much of the condemnation of Zanyiwe Madikizela, better known as Winnie Mandela. She emphasises that it’s strange to perceive Winnie’s actions as motivated by psychiatric reasons rather than political.

She highlights that Winnie was not a radical outlier, but that during 1985-86 many ANC leaders and Radio Freedom, the then banned ANC’s underground radio station, made similar statements about insurrection, killing informers, and necklaces:

Winnie was not the only ANC leader who traded in recklessness and fiery rhetoric. But she was the only woman who was visibly doing so. (p.13)

Msimang also points out that Harry Gwala and other ANC warlords were committing in substance the same actions as Winnie Mandela, but with far less condemnation.

The same double-standards also apply to men and women political leaders having adulterous affairs:

If the roles had been reversed and you had been imprisoned, things would have been very different. Nelson would have remarried and you would have languished forgotten on the island, and it would have been no reflection on him. Men have needs. Women sacrifice.

Unsurprisingly, two such contrasting biographies also differ over the facts. Bridgland writes that the two hit men who assassinated Dr. Abu-Baker Asvat – the Black consciousness exponent and doctor who tended to Stompie after his brutally assault to which Madikizela-Mandela was part – gave statements that Winnie Mandela had offered them R20 000 to kill him. Msimang writes that these were merely “rumours” and “No link has ever been established between Dr. Asvat’s death and Winnie Mandela.”

As this review goes to press, the ANC has posthumously awarded Winnie Mandela its highest honour, the Isithwalandwe.

The controversy continues in death as in life.![]()

Keith Gottschalk, Political Scientist, University of the Western Cape

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the stolen books of Europe – stolen by Nazi Germany and sitting in libraries.

For more visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/14/arts/nazi-loot-on-library-shelves.html

The link below is to an article that takes a look at one man’s love of books.

For more visit:

https://www.npr.org/2019/01/04/678645947/his-love-for-books-reads-like-poetry

Mark Canada, Indiana University and Christina Downey, Indiana University

Each new year, people vow to put an end to self-destructive habits like smoking, overeating or overspending.

And how many times have we learned of someone – a celebrity, a friend or a loved one – who committed some self-destructive act that seemed to defy explanation? Think of the criminal who leaves a trail of evidence, perhaps with the hope of getting caught, or the politician who wins an election, only to start sexting someone likely to expose him.

Why do they do it?

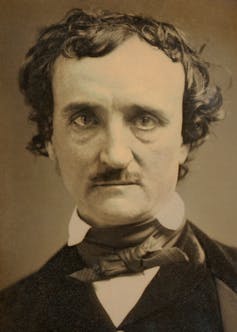

Edgar Allan Poe, one of America’s greatest – and most self-destructive – writers, had some thoughts on the subject. He even had a name for the phenomenon: “perverseness.” Psychologists would later take the baton from Poe and attempt to decipher this enigma of the human psyche.

In one of his lesser-known works, “The Imp of the Perverse,” Poe argues that knowing something is wrong can be “the one unconquerable force” that makes us do it.

It seems that the source of this psychological insight was Poe’s own life experience. Orphaned before he was three years old, he had few advantages. But despite his considerable literary talents, he consistently managed to make his lot even worse.

He frequently alienated editors and other writers, even accusing poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism in what has come to be known as the “Longfellow war.” During important moments, he seemed to implode: On a trip to Washington, D.C. to secure support for a proposed magazine and perhaps a government job, he apparently drank too much and made a fool of himself.

After nearly two decades of scraping out a living as an editor and earning little income from his poetry and fiction, Poe finally achieved a breakthrough with “The Raven,” which became an international sensation after its publication in 1845.

But when given the opportunity to give a reading in Boston and capitalize on this newfound fame, Poe didn’t read a new poem, as requested.

Instead, he reprised a poem from his youth: the long-winded, esoteric and dreadfully boring “Al Aaraaf,” renamed “The Messenger Star.”

As one newspaper reported, “it was not appreciated by the audience,” evidenced by “their uneasiness and continual exits in numbers at a time.”

Poe’s literary career stalled for the remaining four years of his short life.

While “perverseness” wrecked Poe’s life and career, it nonetheless inspired his literature.

It figures prominently in “The Black Cat,” in which the narrator executes his beloved cat, explaining, “I…hung it with the tears streaming from my eyes, and with the bitterest remorse at my heart…hung it because I knew that in so doing I was committing a sin – a deadly sin that would so jeopardise my immortal soul as to place it – if such a thing were possible – even beyond the reach of the infinite mercy of the Most Merciful and Most Terrible God.”

Why would a character knowingly commit “a deadly sin”? Why would someone destroy something that he loved?

Was Poe onto something? Did he possess a penetrating insight into the counterintuitive nature of human psychology?

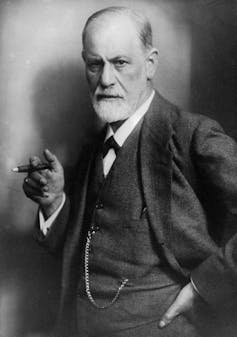

A half-century after Poe’s death, Sigmund Freud wrote of a universal and innate “death drive” in humans, which he called “Thanatos” and first introduced in his landmark 1919 essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.”

Many believe Thanatos refers to unconscious psychological urges toward self-destruction, manifested in the kinds of inexplicable behavior shown by Poe and – in extreme cases – in suicidal thinking.

In the early 1930s, physicist Albert Einstein wrote to Freud to ask his thoughts on how further war might be prevented. In his response, Freud wrote that Thanatos “is at work in every living creature and is striving to bring it to ruin and to reduce life to its original condition of inanimate matter” and referred to it as a “death instinct.”

To Freud, Thanatos was an innate biological process with significant mental and emotional consequences – a response to, and a way to relieve, unconscious psychological pressure.

In the 1950s, the psychology field underwent the “cognitive revolution,” in which researchers started exploring, in experimental settings, how the mind operates, from decision-making to conceptualization to deductive reasoning.

Self-defeating behavior came to be considered less a cathartic response to unconscious drives and more the unintended result of deliberate calculus.

In 1988, psychologists Roy Baumeister and Steven Scher identified three main types of self-defeating behavior: primary self-destruction, or behavior designed to harm the self; counterproductive behavior, which has good intentions but ends up being accidentally ineffective and self-destructive; and trade-off behavior, which is known to carry risk to the self but is judged to carry potential benefits that outweigh those risks.

Think of drunk driving. If you knowingly consume too much alcohol and get behind the wheel with the intent to get arrested, that’s primary self-destruction. If you drive drunk because you believe you’re less intoxicated than your friend, and – to your surprise – get arrested, that’s counterproductive. And if you know you’re too drunk to drive, but you drive anyway because the alternatives seem too burdensome, that’s a trade-off.

Baumeister and Scher’s review concluded that primary self-destruction has actually rarely been demonstrated in scientific studies.

Rather, the self-defeating behavior observed in such research is better categorized, in most cases, as trade-off behavior or counterproductive behavior. Freud’s “death drive” would actually correspond most closely to counterproductive behavior: The “urge” toward destruction isn’t consciously experienced.

Finally, as psychologist Todd Heatherton has shown, the modern neuroscientific literature on self-destructive behavior most frequently focuses on the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with planning, problem solving, self-regulation and judgment.

When this part of the brain is underdeveloped or damaged, it can result in behavior that appears irrational and self-defeating. There are more subtle differences in the development of this part of the brain: Some people simply find it easier than others to engage consistently in positive goal-directed behavior.

Poe certainly didn’t understand self-destructive behavior the way we do today.

But he seems to have recognized something perverse in his own nature. Before his untimely death in 1849, he reportedly chose an enemy, the editor Rufus Griswold, as his literary executor.

True to form, Griswold wrote a damning obituary and “Memoir,” in which he alludes to madness, blackmail and more, helping to formulate an image of Poe that has tainted his reputation to this day.

Then again, maybe that’s exactly what Poe – driven by his own personal imp – wanted.![]()

Mark Canada, Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, Indiana University and Christina Downey, Professor of Psychology, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at how to read big/long books.

For more visit:>br>https://bookriot.com/2018/11/14/reading-big-books/

Albert-László Barabási, Northeastern University

The average American reads 12 or 13 books a year, but with over 3 million books in print, the choices they face are staggering.

Despite the introduction of 100,000 new titles each year, only a tiny fraction of these attract a large enough readership to make The New York Times best-seller list.

Which raises the questions: How does a book become a best-seller, and which types of books are more likely to make the list?

I’m a data scientist. Recently, with help of Burcu Yucesoy, a postdoc in my lab, I put the reading habits of Americans under our data microscope.

We did so by analyzing the sales patterns of the 2,468 fiction and 2,025 nonfiction titles that made The New York Times best-seller list for hardcovers during the last decade.

The first thing the data reminded me is just how few books in my favorite category, science, become best-sellers – a paltry 1.1 percent. Science books compete for a spot on the nonfiction list with everything from business to history, sports to religion.

Yet, on the whole, hardcovers in these categories don’t fly off the shelves, either.

Which nonfiction titles do? Memoir and biographies, with almost half of the 2,025 nonfiction best-sellers falling into this category.

Then we examined the fiction list. Much of the press focuses on literary fiction – books we see debated by critics, lauded as important and culturally relevant, and eventually taught in schools.

But in the past decade, only 800 books categorized as literary fiction made the best-seller list. Most best-sellers – 67 percent of all fiction titles – represent plot-driven genres like mystery or romance or the kind of thrillers that Danielle Steel and Clive Cussler write.

Action sells – there’s no surprise there.

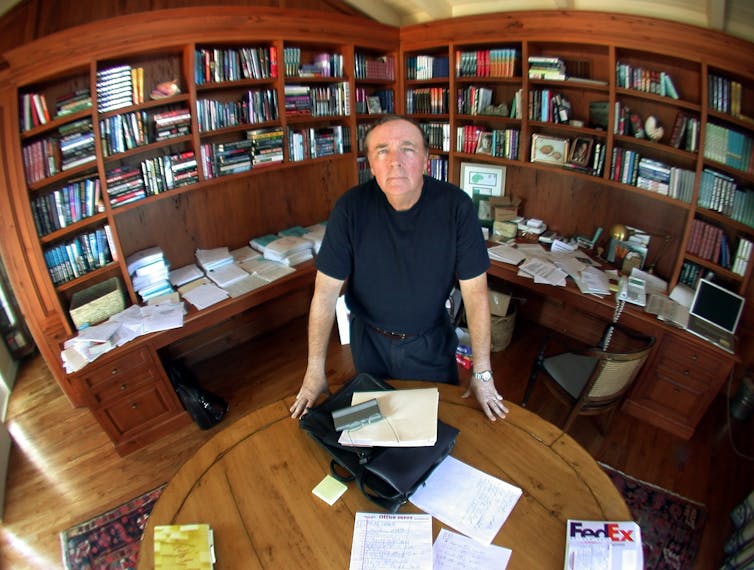

But it was unexpected the degree to which only a handful of authors repeatedly appear: Eight-five percent of best-selling novelists have landed multiple books on the list. Mystery and thriller novelist James Patterson, for example, had 51 books on the best-seller list in the period we explored.

By contrast, only 14 percent of nonfiction authors had more than one best-selling book. Perhaps this is because the genre often requires expertise on a specific subject matter. If an author primarily writes about football, or neuroscience, or even her own life, it’s difficult to generate 10 books on the topic.

Publishers eagerly slap “New York Times Bestseller” stickers on each book that appears on the list’s 15 slots.

A quarter of those, however, have only a cameo appearance, briefly grabbing a spot at the bottom of the list and dropping out after a single week. Only 37 percent have some staying power and spend more than four weeks on the best-seller list. Even fewer – 8 percent – attain the number one spot.

Some rare exceptions can lease out a spot for years: “The Help” by Kathryn Stockett lingered on the fiction list for an astonishing 131 weeks, while Laura Hillenbrand’s “Unbroken” stayed on the nonfiction list for a record 203 weeks.

One big misconception is that you have to write a mega-seller to make the list. The majority of titles on The New York Times best-seller list only sell between 10,000 and 100,000 copies in their first year. “The Slippery Year,” a 2009 memoir by Melanie Gideon, made the list with a yearly sale of fewer than 5,000 copies.

How is this possible?

Our data set shows that just about your only chance of making the list is right after your publication date.

That’s because book sales, we discovered, follow a universal sales curve – there’s a single mathematical formula that captures the weekly sales of all books. And that sales curve has a prominent peak right after the release, meaning you sell the most copies during the first weeks after your book’s release. Fiction sales almost always peak within the first two to six weeks; for nonfiction, the peak can come any time during the first 15 weeks.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/A6uG3/1/

While you might assume that there would be overlooked books that build their audiences slowly and eventually make it onto the hallowed list, there really aren’t.

In other words, what happens during a brief window of time can foretell a book’s success.

For this reason, the timing of the release matters a great deal, especially since the threshold to reach the list varies throughout the year.

In February or March, selling a few thousand copies can land a book on the best-seller list; in December – when sales skyrocket during the holidays – selling 10,000 copies a week might not guarantee a book a spot.

So when should authors publish?

It depends on their circumstances. If they lack a strong fan base, and their hope is to simply make it onto the best-seller list, it’s best to aim for February or March.

At the same time, appearing on The New York Times best-seller list doesn’t necessarily guarantee that a book will sell more copies. Research shows that appearing on the list tends to boost sales only for unknown authors, and the effect disappears after one to three weeks.

So for well-known authors or celebrities who already have built-in fan bases, appearing on the best-seller list might not matter as much. Instead, they’ll likely want to maximize sales – in which case, it’s best to publish in late October: The release will coincide with peak sales in December, when bookstores are packed with Christmas shoppers.

The good news is that if you’re like me – and have written several books that didn’t end up as best-sellers – you still have a chance to break through: Our analysis shows that only 14 percent of novelists made the list with their first book.![]()

Albert-László Barabási, Robert Gray Dodge Professor of Network Science, Northeastern University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.