Kaley Kramer, Sheffield Hallam University

Fresh from the controversy of having to “postpone” awarding the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature, due to a series of scandals that left the prize committee in disarray, the Swedish Academy – which gives out the literature prize – courted controversy again, naming Austrian novelist Peter Handke, as its laureate for 2019.

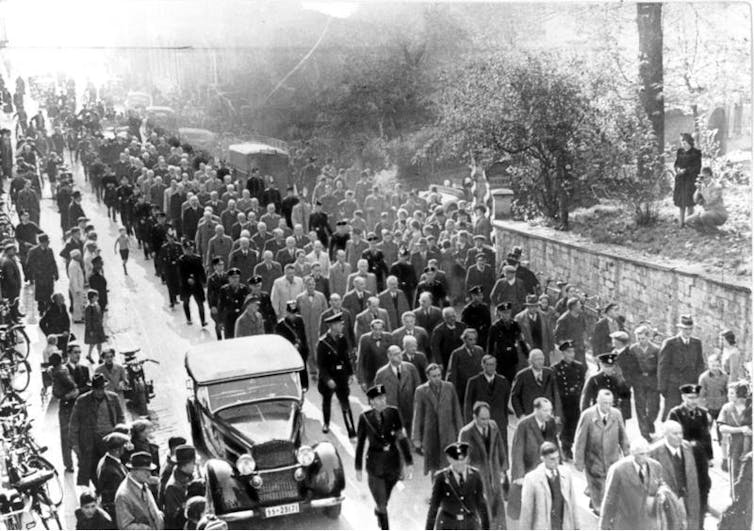

Over the past two decades, Handke has come in for savage criticism for his support for Serbia in the Balkans War in the 1990s and for delivering a eulogy at the funeral of convicted war criminal Slobodan Milosevic in 2006. In the same year, he withdrew his nomination for the Heinrich Heine prize before it could be revoked by politicians. There were also protests in Oslo after he was awarded the Ibsen Prize in 2014.

Less controversial, is the decision to award the delayed 2018 prize to Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk. She is the 16th woman and the fifth Polish writer to be named as a literature laureate. The judges described her as “a writer preoccupied by local life … but looking at earth from above … her work is full of wit and cunning.”

The pair receive 9m Swedish krona (£746,678), which – the judges confirmed – represents the full amount for each year’s prize money.

Scandal strikes

The Swedish Academy, which awards the Nobel Prize in Literature, has been mired in controversy for two years after several members of the committee resigned in 2018 following allegations of financial and sexual misconduct. French photographer Jean-Claude Arnault – whose wife, the poet Katarina Frostenson, was a committee member, was accused of rape in 2017 and was sentenced to two years imprisonment in 2018. His wife left the academy earlier this year after allegations of conflict of interest and the leaking of Nobel winners’ names.

Read more:

Nobel Prize crisis: flurry of withdrawals rocking Swedish Academy’s showpiece literature award

At the time, the executive director of the Nobel Foundation, Lars Heikensten, said is was important the Swedish Academy “quickly solves their problems. If they manage to do that in a way that restores confidence, they will be able to continue to award the Nobel Prize in Literature”.

Whether or not the academy has heeded the implied threat in Heikensten’s words, it seems quite ambitious to demand a “quick” solution. Over the year, several additional points of needed reform have been suggested, from revising the statutes to reconsidering the eligibility criteria for the award.

Lofty ideals and purity of spirit

The Nobel Prize in Literature is one of the more mysterious awards. According to the will of the founder, Alfred Nobel, the prize is awarded to writers who “have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”.

This has been interpreted since in different ways. French poet Sully Prudhomme, who won the first literature Nobel in 1901, was awarded for his poetry’s “lofty idealism”, while Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Martinus Bjørnson won in 1903 for “the rare purity of [his poetry’s] spirit”. The following year, French writer Frédéric Mistral was awarded for “fresh originality and true inspiration”. The first female literature laureate, Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf (1909), was given the prize “in appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterise her writings”.

Quite what Nobel meant by an “ideal direction” has never been decisively stated and the academy has, over time, selected and discounted work depending on a very fluid consensus on how the term might be understood and applied.

Most recently, Tokarczuk was awarded for “a narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life”. Meanwhile, the judges said Handke won “for an influential work that with linguistic ingenuity has explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience”.

An ‘ideal direction’

The “ideal direction” that the prize should take, particularly after 2018, has been less ambiguous. As of yesterday, only 15 of 116 literature laureates have been women. And the desire for a “global distribution” of prize winners is equally out of step with the actual awards – winners from the global North overwhelmingly dominate the list of laureates, as do white writers. Works written in English have also been dominant – 29 laureates published their work in English and the next most awarded language is French at 14.

Things have changed, slowly, since the 1980s. Laureates have become more diverse in nationality and language, while eight of the 15 female laureates were awarded between 1991 and 2015.

The need for reform of the academy and Nobel prize judging had been building for some time. The Swedish Academy, founded in 1786 by Gustav III, is comprised of 18 members who were until 2018 elected for life and were not permitted to resign their position. There had, however, been a number of withdrawals – in 1989, two members quit the academy after it refused to condemn Iran after it issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie for The Satanic Verses. In 2005, academy member Knut Ahnlund quit in protest at the decision to give the 2004 prize to Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek whose work, he said, was “static and completely engulfed in cliché”.

Academy members can now voluntarily resign, which means that the seats of those who have withdrawn can be filled with new members. This will at least ensure regular injections of fresh blood and new energy. But real reform in the literary prize industry, if this year’s selection for the Nobel Prize is any indication, remains slow – and what is meant by “reform” is as vague as Nobel’s “ideal direction”.![]()

Kaley Kramer, Deputy Head of English/Principal Lecturer, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.