The link below is to an article reporting on the longlist for the 2021 Richell Prize.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/09/06/192716/richell-prize-2021-longlist-announced/

The link below is to an article reporting on the longlist for the 2021 Richell Prize.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/09/06/192716/richell-prize-2021-longlist-announced/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2021 James Tait Black prizes.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/08/26/192178/von-reinhold-ni-ghriofa-win-james-tait-black-prizes/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2021 Ned Kelly Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/08/26/192166/ned-kelly-awards-2021-winners-announced/

The link below is to an article that reports on the winners of the 2021 Western Australia’s Premier’s Awards.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2021/08/26/192143/wa-premiers-book-awards-announced/

Blair Williams, Australian National University

This week, a new Australian political biography will appear on bookshelves. This is The Accidental Prime Minister, an examination of Scott Morrison by journalist Annika Smethurst.

While a prime minister makes for an obvious – and worthy — biographical subject, it also continues Australia’s strong tradition of focusing on the stories of men in politics.

History as a discipline may have been grappling with gender issues since the 1970s, but political history has been especially resistant to questions about women and gender.

In a recent study for the Australian Journal of Biography and History, I looked at Australian political biographies over the past decade. I found female political figures are almost always ignored.

Political biographies add life, colour and depth to historical events and personalities. They can shape the legacies of politicians long after they’ve left politics. They also show us who is worthy of being written about and who is overlooked in the pages of history.

However, most Australian political biographies have been written about men, particularly male prime ministers.

This inevitably calls to mind the enduring myth of the “Great Man” as the architect of historical change. This is best described by 19th century historian Thomas Carlyle, who believed “the history of the world is but the biography of great men”.

As women were largely excluded from politics until the end of the 20th century, it could be argued they simply haven’t had the opportunity to be seen as “great politicians” worthy of literary examination.

Yet, as political biographies define which personal and political qualities suggest “greatness”, it could also be argued we tend to associate these qualities with men and masculinity. Male leaders’ gender is never discussed or explored in their political biographies. Masculinity is portrayed as the unseen norm while gender is an attribute only ever identified with women.

This argument gains further support from the fact there are more women in Australian politics than ever before, yet there remains a notable lack of political biographies covering their lives and stories. In my study, I examined Australian political biographies published in the past decade. Only four out of 31 were on women politicians.

This small minority includes Margaret Simons’ Penny Wong in 2019 and Anna Broinowski’s 2017 biography of Pauline Hanson, Please Explain.

There are three key factors that can explain the lack of biographies written on Australian women politicians.

First, as previously noted, there is the lack of gender parity in Australian politics. The 1990s saw a surge of women enter politics, partly due to Labor’s gender quotas. Yet at the moment, only 31% of the House of Representatives are women and all major leadership positions are held by men.

Read more:

Why is it taking so long to achieve gender equality in parliament?

Second, Australian political biography itself has a role to play here — the Great Man narrative is an enduring problem. It leads to an overemphasis on so-called “foundational patriarchs” and overlooks the impact of political players who don’t conform to this stereotype.

In the past decade, two biographies each were written on former Labor prime ministers Paul Keating and Bob Hawke and former Liberal prime minister Robert Menzies. Another biography on former Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam added to the ever-growing stack of tomes dedicated to these leaders.

Third, women politicians might be more hesitant to expose their private lives to the same extent as their male counterparts. Women politicians frequently experience sexist media coverage that often scrutinises their personal choices as a reflection of their professional capabilities. It is hardly shocking that they might be hesitant to cede agency over their own story and endorse an official biography.

So, there are several glaring omissions in Australian political biography. Where is the biography of our first woman prime minister, Julia Gillard? Former deputy prime minister Julie Bishop is another that comes to mind.

There is also pioneering former Labor minister Susan Ryan, who was pivotal in the passing of the Sex Discrimination Act, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act and the Affirmative Action Act. And Natasha Stott Despoja, the youngest woman to sit in the Australian parliament and former leader of the Australian Democrats.

So where are all the great women political figures? Well, they’re in the memoir section.

Through my research, since 2010, I found 12 autobiographies and memoirs have been published by women premiers, party leaders, federal and state MPs and senators, lord mayors and, of course, our first and only woman prime minister (though I also counted over 30 written by male politicians).

Autobiographies can be a valuable way for women politicians to recover their voices, reassert their agency and reclaim their public identity by telling their own life story.

An ambition to take charge of their public image is a common thread running through these books, usually paired with a desire to expose sexism. Gillard’s autobiography My Story, published in 2014 (the year after she left politics), is a notable example of this, holding her opponents and the media to account for their frequently sexist behaviour.

Many women from across the political spectrum have now published comparable memoirs, including Labor MP Ann Aly, former Greens leader Christine Milne and former independent MP Cathy McGowan.

This year, former Labor cabinet minister Kate Ellis’ Sex, Lies and Question Time and former Liberal MP Julia Banks’ Power Play have provided two more examples of how women politicians — particularly those who’ve left politics — use the power of memoir to reclaim their stories and critique the sexist culture in parliament.

While it’s great women are using memoirs to voice their stories, we should not give up on conventional political biography.

As this genre continues to shape our understanding of political culture and history, it is more important now than ever that women are included to dispel once and for all the myth that their stories are not worth recording.

Rather than adding to the sexist speculation that women politicians experience, political biographers should offer their support for these stories to be told in a consensual and meaningful manner.![]()

Blair Williams, Research Fellow, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership (GIWL), Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Julian Novitz, Swinburne University of Technology

Email newsletters might be associated with the ghost towns of old personal email addresses for many: relentlessly accumulating unopened updates from organisations, stores and services signed up to and forgotten in the distant past. But over the last few years they have experienced a revival, with an increasing number of writers supplementing their income with paid newsletter subscriptions.

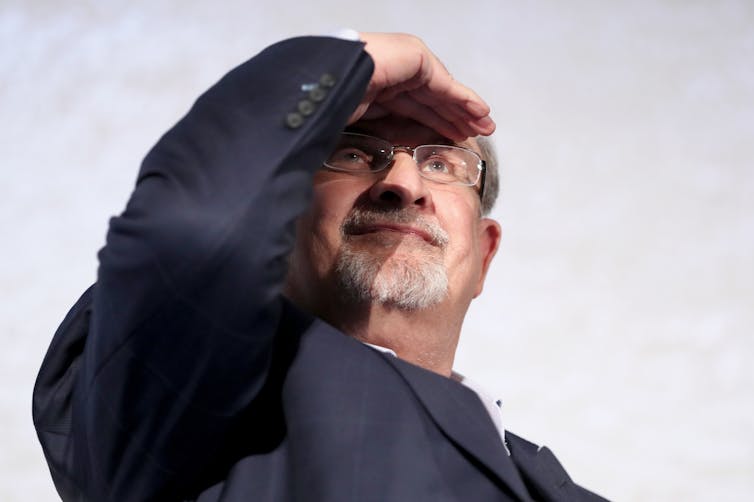

Most recently, Salman Rushdie’s decision to use the newsletter subscription service Substack to circulate his latest book has sparked conversation around this platform and its impact on the world of publishing.

Launched in 2017, Substack allows writers to create newsletters and set up paid subscription tiers for them, offering readers a mixture of free and paywalled content in each edition.

Substack has thus encroached on the traditional territories of newspapers, magazines, the blogosphere – and now trade publishing. Though it is worth noting that until now it has been most enthusiastically adopted by journalists rather than authors.

Rather than monetising the service via advertising, Substack’s profits come from a percentage of paid subscriptions. Substack’s founders see the platform as a way of breaking from the ‘attention economy’ promoted by social media, allowing a space for more thoughtful and substantial writing that is funded directly by readers.

Read more:

Substack isn’t a new model for journalism – it’s a very old one

Rushdie’s decision to publish via Substack signals a surprising inroad into one of the areas associated with trade publishing – literary fiction – and certainly makes for a good news story. He is the first significant literary novelist to publish a substantial work of fiction via the platform and Rushdie himself talks jokingly about helping to kill off the print book with this move.

However, the novella that Rushdie is intending to serialise will almost certainly be available in a more conventional format at some point in the future, given all Substack writers retain full rights to their intellectual property.

Other experiments with digital self-publication by prominent fiction authors, such as Stephen King’s novella Riding the Bullet (first published independently as an eBook), and the fiction first generated on Twitter by writers like David Mitchell and Neil Gaiman, have made their way to traditional publishers.

While this movement provides excellent publicity for Rushdie and the Substack service, it’s perhaps better understood as a limited term platform exclusivity deal than as a radical disruption of the literary publishing ecosystem.

Potentially more interesting is what the “acquisition” of Rushdie by Substack illustrates about their operation as a digital service. Throughout its history, Substack has offered advances to promising writers to support them while they cultivate a subscriber base.

This practice has now been formalised as Substack Pro, where selected writers, like Rushdie himself, are paid a substantial upfront fee to produce content, which Substack recoups by taking a higher percentage of their subscription fees for their first year of writing.

The exact sums paid vary between writers, but it is not dissimilar to a traditional advance on royalties. When coupled with some of the other services that are available to writers with paid subscriptions – like a legal fund and financial support for the editing, design, and production of newsletters – Substack can be seen as operating in a grey area between publisher and platform.

They pursue promising and high-profile writers, generate income, and provide services in ways that parallel the operations of trade publishers, but do not claim rights or responsibilities in relation to the content that is produced.

Although Substack do not see themselves as commissioning writers it could be argued they do play an editorial role in curating content on their platform through not terribly transparent Substack Pro deals and incentives.

Recently Jude Doyle, a trans critic and novelist, has abandoned the platform. They note the irony of how profits generated by the often marginalised or subcultural writers who built paid subscriber bases in the early days of Substack are now being used to fund the much more lucrative deals offered to high-profile right-wing writers, who have in some cases exploited Substack’s weak moderation policy to spread anti-trans rhetoric and encourage harassment.

It could be argued Substack Pro is evolving into an inversion of the traditional (if somewhat idealised) publishing model, where a small number of profitable authors would subsidise the emergence of new writers. Instead, on Substack, profits generated from the work of large numbers of side-hustling writers are used to draw more established voices to the platform.

The founders of Substack have been unapologetic about their policies, considering the “unsubscribe” button to be the ultimate moderation tool for their users. They do, however, acknowledge Substack’s free-market approach may not appeal to all and anticipate competition from alternatives.

Ghost already exists as a non-profit newsletter platform with a more active approach to moderation, and Facebook’s Bulletin provides a carefully curated newsletter service from commissioned writers.

At this stage, the use of newsletters for literary fiction is an experiment, and it remains to be seen if it will be sustainable. As Rushdie puts it: “It will either turn out to be something wonderful and enjoyable, or it won’t.”![]()

Julian Novitz, Lecturer, Writing, School of Media and Communication, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hi all. Once again I have been encountering a noticeable decline in my health, so will be taking a ‘preventative break’ over the next week or so. There will be no posts until Saturday the 25th of September 2021 or thereabouts.

Stacy Gillis, Newcastle University

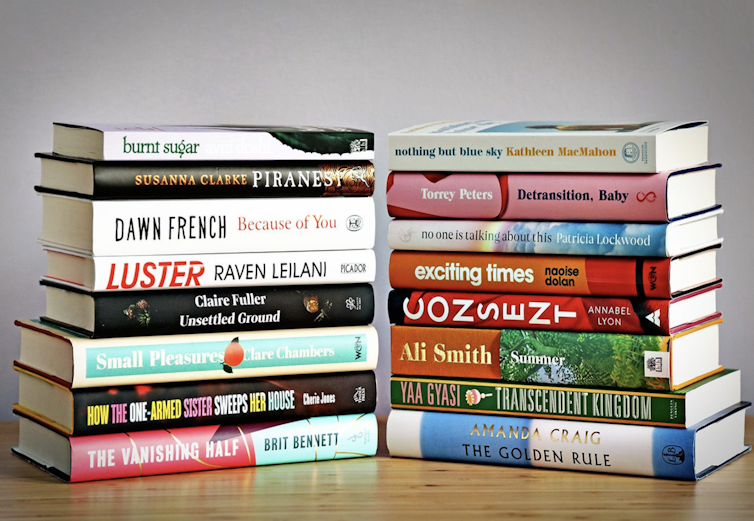

Every year since 1996, one of the most heralded of awards for women writing in English is announced annually. The prize formerly known as the Orange Prize, the Orange Broadband Prize, and Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, has – since 2018 – been anonymously supported by a “family” of sponsors, and known simply as the Women’s Prize for Fiction. And the 2021 winner is Susanna Clarke, with her second novel Piranesi.

Clarke’s latest book was described by this year’s chair of judges and former Booker winner, Bernardine Evaristo, as a book that “would have a lasting impact”. It comes 17 years after Clarke’s first novel, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, which blends historical fiction with imaginative fantasy.

Every year, there is some discussion in parts of the press, and on social media, on the point of a prize for women writers. After all, the argument goes, Anglophone women writers have won such awards as the Booker – Hilary Mantel and Margaret Atwood, for example, while many of those shortlisted are also women. Meanwhile, Doris Lessing and Alice Munro have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Do we need an award specifically for women?

Ever since the prize was first mooted in the early 1990s, many have wondered whether the prize is necessary, patronising, or even fair. A common position amongst its detractors is that the prize is sexist and discriminatory. English journalist and novelist, Auberon Waugh, (the eldest son of the novelist Evelyn Waugh) famously called it the Lemon Prize.

These debates about women writers have their origin, however, in the longstanding concerns and debates about the relationship between women, reading and writing: debates which are nearly as old as the history of the novel in English.

For example, the poet and priest Thomas Gisborne’s 1797 conduct manual, An Enquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex, recommends to every woman “the habit of regularly allotting to improving books a portion of each day”. But Gisborne does not include novels among his “improving books” – like many of those who have written on the possible dangers of reading fiction for women.

This policing of the woman reader – and it is a short skip and jump here to the woman writer – is far from an isolated occurrence. In January 1855, the novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote to his publisher that, “America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash – and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed”. Hawthorne was concerned with the subject matter of women writers – quite simply, it was not to his taste.

This dismissal of women writers continues today. In an interview at the Royal Geographic Society in 2011, the British writer, V.S. Naipaul, was asked if he considers any woman writer his match, to which he replied “I don’t think so”. He claimed that he could “read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not”. Naipaul was clear that part of this recognition was because writing by women is “unequal” to him and his writing. Key to this is that the subject matter of women’s writing is often perceived as frivolous and unimportant.

This separation or segregation of women’s writing should be understood as part of the patriarchal control of what and who matters – and, historically, women have not. The Women’s Prize for Fiction was set up in response to the Booker Prize of 1991 when none of the six shortlisted books were by women, despite 60% of the novels published that year by women writers.

Not all potential entrants welcomed the new prize. A.S. Byatt (winner of the 1990 Man Booker Prize) refused to have her fiction submitted for consideration for the new award, and trivialised the Women’s Prize for the assumption that there is something that might be grouped together as a “feminine subject matter”. But it is an indisputable fact that women have often been excluded from or dismissed by the literary establishment, by reviewers, and by the prize system.

This is not to say all women’s writing experiences are the same. There are challenges to the notion of awards for women’s writing – since they can still discriminate against different races, ages, types of education, classes, disability and trans women,among others. But what cannot be disputed is that all women (writers or not) are united by living in global and local societies that value, promulgate and prioritise the voice, identities and experiences of men over women.

The positions offered by Gisborne, Hawthorne and Naipaul are indicative of the expectations placed upon women in the literary marketplace and are very much tied to issues around the relationship between worth, taste and power. Who decides what text has “worth”, and how this worth has been arrived at, are questions that we might think are something for English literature students to grapple with at university.

But these are important questions for us all to consider. The humanities is broadly the study of what it is to be human and reading is a key marker of being human. We tell stories to ourselves, about ourselves, over and over again. We have entire industries built on reading, and on storytelling (whether books, films, games or more). We all need to think about who reads, and whose stories are told and re-told. The Women’s Prize for Fiction is one way of ensuring that women’s stories are among those that are told and re-told.![]()

Stacy Gillis, Senior Lecturer in Twentieth-Century Literature and Culture, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Laura Ingallinella, Wellesley College

When Dante Alighieri died 700 years ago, on Sept. 14, 1321, he had just put his final flourishes on the “Divine Comedy,” a monumental poem that would inspire readers for centuries.

The “Divine Comedy” follows the journey of a pilgrim across the three realms of the Christian afterlife – hell, purgatory and paradise. There, he encounters a variety of characters, many of whom are based on real people Dante had met or heard of during his life.

One of them is a woman named Sapia Salvani. Sapia meets Dante and his first guide, Virgil, on the second terrace of purgatory. She tells the two how her fate in the afterlife was sealed – how she stood at the window of her family’s castle and, with troops gathering in the distance, prayed for her own city, Siena, to fall. Despite their advantage, the Sienese were slaughtered – including Sapia’s nephew, whose head was paraded around Siena on a pike.

Sapia, however, felt triumphant. According to Dante and medieval theologians, she had fallen prey to one of the seven capital vices, “invidia,” or envy.

The portrayal of Sapia in the “Divine Comedy” is imbued with political implications, many of which boil down to the fact that Dante blamed the violence of his time on those who turned against their communities out of arrogance and greed.

But the real Sapia was even more interesting than Dante would have you believe. Documentary sources reveal that she was a committed philanthropist: With her husband, she founded a hospice for the poor on the Via Francigena, a pilgrimage route to Rome. Five years after witnessing the fall of Siena, she donated all her assets to this hospice.

Sapia is one among many characters from the “Divine Comedy” that deserve to be known beyond – and not just because of – what Dante decided to say about them in his poem. With my students at Wellesley College, I’m reviving the real stories behind the characters of Dante’s masterpiece and making them available to everyone on Wikipedia. And it was especially important for us to start with his female characters.

Among the 600 characters appearing in the “Divine Comedy,” women are the least likely to appear in the historical record. Medieval authors tended to write biased accounts of women’s lives, motives and aspirations – if not ignore them altogether. As a result, the “Divine Comedy” is often the only accessible source of information on these women.

At the same time, Dante’s treatment of women isn’t free from misogyny. Scholars such as Victoria Kirkham, Marianne Shapiro and Teodolinda Barolini have shown that Dante relished turning women into metaphors, from pious maidens to villainesses capable of bringing dynasties to their knees.

For this reason, fuller pictures of Dante’s women have been elusive. As a researcher, you’re lucky if you can come across a contemporary who supported or built upon Dante’s tangled reinvention, or documents in which the woman in question is mentioned as mother, wife or daughter.

The more my students asked me about the women in the poem, the more I wondered: What if we found a way to tell everyone their stories? So I approached Wiki Education, a nonprofit that fosters the collaboration between higher education and Wikipedia, to see if they would partner with me and my students. They agreed.

The recipe behind Wikipedia’s two decades of success is its stunning simplicity: an open encyclopedia written and maintained by a worldwide community of volunteers who draft, edit and monitor its free content.

Wikipedia’s status as a crowdsourced work is one of its greatest strengths, but it’s also its greatest weakness in that it reflects the world’s systemic flaws: The vast majority of Wikipedia contributors identify as male.

In 2014, only 15.5% of Wikipedia’s biographies in English were about women. By 2021, that number had risen to 18.1%, but that was after more than six years of sustained efforts aimed at bolstering the representation of women on Wikipedia by creating new entries and referencing scholarship authored by women.

For my students, researching and composing Wikipedia entries on Dante’s characters doubled as advocacy.

Writing for Wikipedia is different from writing an essay. You must be unbiased, avoid personal flourishes and always back your statements with external references. Rather than producing an argument, you offer readers the tools to build an argument of their own.

And yet the very act of writing an entry about a person does advance a specific argument: that their life is worth being the focus of attention, rather than an easily forgettable name in the backdrop of a grand narrative. This choice is a radical one. It’s an affirmation that someone possesses historical value beyond the fact that they provided a spark of inspiration to an author.

Pursuing this goal was not without challenges; it could be difficult to maintain an unbiased tone while telling stories of violence and abuse.

That was the case with Ghisolabella Caccianemico, a young woman from Bologna sold into sexual slavery by her brother, Venèdico, who hoped to form an alliance with a neighboring marquis. Dante told his readers a “filthy tale” that would make them indignant. In it, Ghisolabella is a silent victim surrounded by men.

However, we turned Ghisolabella into the subject of her story, threading the fine line between giving a starkly objective account of the violence she suffered and preserving her dignity.

“Ghisolabella’s extramarital relation[s] with the marquis, though against her will, was ruinous to her status,” wrote my student, citing early 20th-century scholars who canvassed the archives of Bologna for evidence on Ghisolabella.

“Dante’s inclusion of Ghisolabella,” she added, “eternalizes Venèdico’s sin.”

Researching these women also turned into an opportunity to upend Dante’s personal views.

Take Beatrice d’Este, a noblewoman Dante criticizes for marrying again after her first husband died. Dante was outraged by widows who dared to remarry instead of remaining forever faithful to their late spouses. Not everyone, however, agreed with his defamation of Beatrice.

To tell Beatrice’s story, my student just needed to look into the right places – namely, an exceptional article by Deborah W. Parker, who put Dante’s treatment of Beatrice into context.

Parker explains how Beatrice was likely pressured into her second marriage and tried to negotiate her place in a world that subjected her to slander. By having the family crests of her two husbands carved side by side on her tomb, she made a pregnant statement about her identity and allegiances.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Thanks to our work, in addition to Ghisolabella and Beatrice d’Este, there are now over a dozen biographies of these women on Wikipedia: Alagia Fieschi, Cianghella della Tosa, Constance of Sicily, Cunizza da Romano, Gaia da Camino, Giovanna da Montefeltro, Gualdrada Berti, Joanna of Gallura, Matelda, Nella Donati, Pia de’ Tolomei, Piccarda Donati and Sapia Salvani. They join Beatrice Portinari and Francesca da Rimini, the only two historical women from the “Divine Comedy” who had acceptable entries on Wikipedia prior to our work.

As feminist theorist Sara Ahmed writes in “Living a Feminist Life,” “citations can be feminist bricks: they are the materials through which, from which, we create our dwellings.”

One brick at a time – one page, revision or added reference at a time – Wikipedians can broaden our understanding of the past, centering women’s stories in a world that has long edited them out.![]()

Laura Ingallinella, Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Italian Studies and English, Wellesley College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Adam Haupt, University of Cape Town

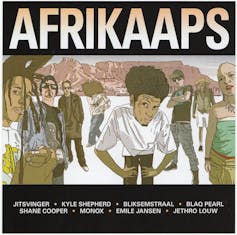

It’s been in existence since the 1500s but the Kaaps language, synonymous with Cape Town in South Africa, has never had a dictionary until now. The Trilingual Dictionary of Kaaps has been launched by a collective of academic and community stakeholders – the Centre for Multilingualism and Diversities Research at the University of the Western Cape along with the hip hop-driven community NGO Heal the Hood Project. The dictionary – in Kaaps, English and Afrikaans – holds the promise of being a powerful democratic resource. Adam Haupt, director of the Centre for Film & Media Studies at the University of Cape Town, is involved in the project and tells us more.

Kaaps or Afrikaaps is a language created in settler colonial South Africa, developed by the 1500s. It took shape as a language during encounters between indigenous African (Khoi and San), South-East Asian, Dutch, Portuguese and English people. It could be argued that Kaaps predates the emergence of an early form of Kaaps-Hollands (the South African variety of Dutch that would help shape Afrikaans). Traders and sailors would have passed through this region well before formal colonisation commenced. Also consider migration and movement on the African continent itself. Every intercultural engagement would have created an opportunity for linguistic exchange and the negotiation of new meaning.

Today, Kaaps is most commonly used by largely working class speakers on the Cape Flats, an area in Cape Town where many disenfranchised people were forcibly moved by the apartheid government. It’s used across all online and offline contexts of socialisation, learning, commerce, politics and religion. And, because of language contact and the temporary and seasonal migration of speakers from the Western Cape, it is written and spoken across South Africa and beyond its borders.

It is important to acknowledge the agency of people from the global South in developing Kaaps – for example, the language was first taught in madrassahs (Islamic schools) and was written in Arabic script. This acknowledgement is imperative especially because Afrikaner nationalists appropriated Kaaps in later years.

For a great discussion of Kaaps and explanation of examples of words and phrases from this language, listen to this conversation between academic Quentin Williams and journalist Lester Kiewit.

The dictionary project, which is still in its launch phase, is the result of ongoing collaborative work between a few key people. You might say it’s one outcome of our interest in hip hop art, activism and education. We are drawn to hip hop’s desire to validate black modes of speech. In a sense, this is what a dictionary will do for Kaaps.

Quentin Williams, a sociolinguist, leads the project. Emile Jansen, Tanswell Jansen and Shaquile Southgate serve on the editorial board on behalf of Heal the Hood Project, which is an NGO that employs hip hop education in youth development initiatives. Emile also worked with hip hop and theatre practitioners on a production called Afrikaaps, which affirmed Kaaps and narrated some of its history. Anthropologist H. Samy Alim is the founding director of the Center for Race, Ethnicity and Language at Stanford University and has assisted in funding the dictionary, with the Western Cape’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport.

We’re in the process of training the core editorial board in the scientific area of lexicography, translation and transcription. This includes the archiving of the initial, structured corpus for the dictionary. We will write down definitions and determine meanings of old and new Kaaps words. This process will be subjected to a rigorous review and editing and stylistic process of the Kaaps words we will enter in the dictionary. The entries will include their history of origin, use and uptake. There will also be a translation from standard Afrikaans and English.

It will be a resource for its speakers and valuable to educators, students and researchers. It will impact the ways in which institutions, as loci of power, engage speakers of Kaaps. It would also be useful to journalists, publishers and editors keen to learn more about how to engage Kaaps speakers.

A Kaaps dictionary will validate it as a language in its own right. And it will validate the identities of the people who speak it. It will also assist in making visible the diverse cultural, linguistic, geographical and historical tributaries that contributed to the evolution of this language.

Acknowledgement of Kaaps is imperative especially because Afrikaner nationalists appropriated Kaaps in order to create the dominant version of the language in the form of Afrikaans. A ‘suiwer’ or ‘pure’ version, claiming a strong Dutch influence, Afrikaans was formally recognised as an official language of South Africa in 1925. This was part of the efforts to construct white Afrikaner identity, which shaped apartheid based on a belief in white supremacy.

Read more:

Afrikaner identity in post-apartheid South Africa remains stuck in whiteness

For example, think about the Kaaps tradition of koesiesters – fried dough confectionery – which was appropriated (taken without acknowledgement) and the treats were named koeksisters by white Afrikaners. They were claimed as a white Afrikaner tradition. The appropriation of Kaaps reveals a great deal about the extent to which race is socially and politically constructed. As I have said elsewhere, cultural appropriation is both an expression of unequal relations of power and is enabled by them.

When people think about Kaaps, they often think about it as ‘mixed’ or ‘impure’ (‘onsuiwer’). This relates to the ways in which they think about ‘racial’ identity. They often think about coloured identity as ‘mixed’, which implies that black and white identities are ‘pure’ and bounded; that they only become ‘mixed’ in ‘inter-racial’ sexual encounters. This mode of thinking is biologically essentialist.

Read more:

How Cape Town’s “Gayle” has endured — and been adopted by straight people

Of course, geneticists now know that there is not sufficient genetic variation between the ‘races’ to justify biologically essentialist understandings. Enter cultural racism to reinforce the concept of ‘race’. It polices culture and insists on standard language varieties by denigrating often black modes of speech as ‘slang’ or marginal dialects.

Visibility and the politics of representation are key challenges for speakers of Kaaps – be it in the media, which has done a great job of lampooning and stereotyping speakers of Kaaps – or in these speakers’ engagement with governmental and educational institutions. If Kaaps is not recognised as a bona fide language, you will continue to see classroom scenarios where schoolkids are told explicitly that the way in which they speak is not ‘respectable’ and will not guarantee them success in their pursuit of careers.

This dictionary project, much like ones for other South African languages like isiXhosa, isiZulu or Sesotho, can be a great democratic resource for developing understanding in a country that continues to be racially divided and unequal.![]()

Adam Haupt, , University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.