James McGonigal, University of Glasgow

Grey over Riddrie the clouds piled up,

dragged their rain through the cemetery trees.

The gates shone cold. Wind rose

flaring the hissing leaves, the branches

swung, heavy, across the lamps.

From King Billy (1963)

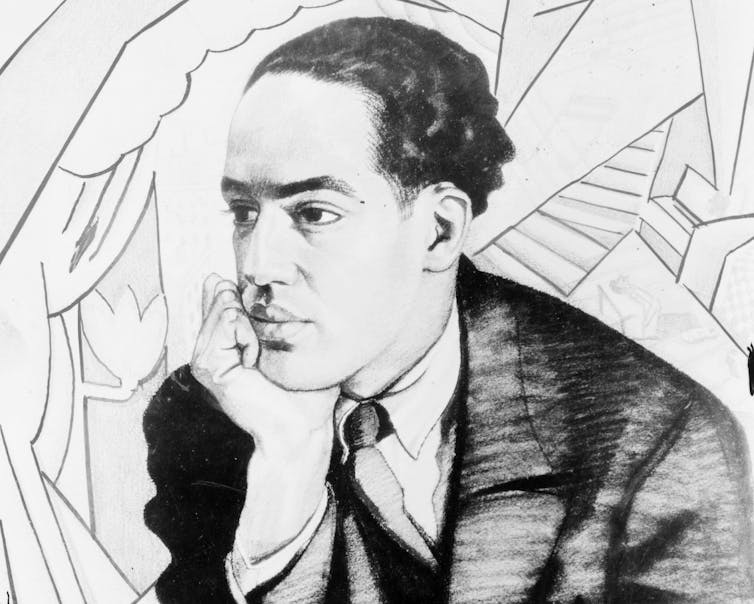

Why do we remember particular poems and poets – and happily forget others? The Scottish poet Edwin Morgan was born 100 years ago, and this week marks the the start of a year of celebration of the man and his work. It goes ahead in a virtual way, with public events cancelled in days of lockdown or deferred to 2021 – an advantage of a year-long celebration.

Born in Glasgow on April 27, 1920, Edwin George Morgan led a remarkable and wide-ranging creative life. He published 25 collections of his own poetry and translated hundreds of Russian, Hungarian, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French and German poems too. He also wrote plays, opera libretti, radio broadcasts, journalism, book and drama reviews and literary criticism.

His work continues to be published, produced, taught and celebrated. His poetry is memorable not only for Glasgow, his native city, and for Scotland – but for a wider audience thanks to Morgan’s lifelong concern with universal and cosmic matters.

Glasgow and Scotland

Morgan loved the city of his birth for its energy, industrial inventiveness, humour and crowded streets. He warmed to its humanity, shared its sorrows, wrote against scarring deprivation, recovered its history (real and imagined), and projected several Glasgows into the future.

He celebrated its changing cityscape in The Starlings in George Square, and its interactive street culture in Trio, where we encounter three Glaswegians bearing Christmas gifts of a guitar festooned with mistletoe, a new baby and a chihuahua, cosy in a tartan coat. He recorded the darker elements of Glasgow too, such as the city’s sectarian violence and notorious tribal gang culture in King Billy.

The directness of these interactions is carried in authentic urban speech rhythms new to Scottish poetry at the time. In the Snack-bar and Death in Duke Street vividly describe the long deprivation and the sudden death that are also part of the scene:

Only the hungry ambulance

howls for him through the staring squares.

Morgan taught English at Glasgow University all his working life, and became the city’s first poet laureate in 1999. He became Scotland’s laureate too, in 2004 – its first “makar” or national poet. He celebrated Scotland’s varied landscapes, people and places, whether humorously in Canedolia, or reflectively in Sonnets from Scotland.

For Morgan, part of a poet’s job was to remind Scots that if they want to achieve something in the world and to really be taken seriously, then they need to find words to show the world what they stand for. Poets and other writers can help them to do this. When Scotland’s ambitious new parliament building opened at Holyrood at the foot of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, he wrote:

What do the people want of the place? They want it to be filled with thinking

persons as open and adventurous as its architecture.

A nest of fearties is what they do not want.

A symposium of procrastinators is what they do not want.

A phalanx of forelock-tuggers is what they do not want.

And perhaps above all the droopy mantra of “it wizny me” is what they do not want.

Lines from For the Opening of the Scottish Parliament, October 9 2004

The world, the universe and love

Morgan travelled widely – to Africa and the Middle East during the second world war, to Russia and Eastern Europe during the Cold War, to the US, New Zealand and the North Pole. These are the places he writes of in his poetry. The New Divan is his mysterious war poem in which he records in 100 sharp filmic stanzas, memories from the second world war desert campaign that shift like characters in an Arabian Nights tale – and yet are modern soldiers and lovers too.

Space and time travel fascinated him. A supersonic flight by Concorde to Lapland was the nearest he could actually get to outer space, where he had often journeyed in his imagination. The First Men on Mercury dramatises a linguistic encounter between Western astronauts and Mercurian beings that ends in a complete and hilarious transposition of language and power. Morgan believed that humanity would ultimately endeavour to create “A Home in Space”, which is the title of another poem that follows “a band of tranquil defiers” who decide to cut off all connection with the Earth.

This was a poet who could speak as a space module or a Mercurian, and also as an apple, a computer, an Egyptian mummy. He was an acrobat of words and identities. Perhaps his own identity as a gay man, risking censure or imprisonment through most of his life, encouraged that ability to shape-shift. His love poems are haunting. Some deal with loss or transience, as in One Cigarette, or Absence, or Dear man, my love goes out in waves, or with the physical risks of a forbidden lifestyle, as in Glasgow Green or Christmas Eve, which tells of a fleeting encounter with another man on a bus.

But his poems also celebrate ways in which all lovers share the tender details of everyday life together, as in Strawberries. His writing of gay and queer experience had a significant impact on social attitudes and political change in Scotland. His voice spoke for many young or isolated gay people, with an advocacy that was subtle but powerful in effect.

Collaboration

Morgan was an individualist, in some senses a loner. And yet he was also an inspirer of creative partnerships – in art, photography, opera, music and drama, cultural journalism and poetry in performance. His early support was invaluable to an array of groundbreaking poets and artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay, Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and Jackie Kay, and he enjoyed collaborations with Scots musicians such as jazz saxophonist Tommy Smith and indie band Idlewild.

Such lists could be extended. They continue to grow through the Edwin Morgan Trust, set up to administer his cultural legacy by supporting new poets and poetry in Scotland and Europe as well as wider artistic responses to Morgan’s work. There are centenary publications too with new collections of selected poems and prose. For those who loved this quiet man of Scottish poetry it promises to be a memorable year.![]()

James McGonigal, Emeritus Professor of English in Education, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.