The link below is to an article reporting on the surge in writing during the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2020/mar/26/novel-writing-during-coronavirus-crisis-outbreak

The link below is to an article reporting on the surge in writing during the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2020/mar/26/novel-writing-during-coronavirus-crisis-outbreak

The link below is to an article that considers the place of literature during a pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/shirazi-boccaccio-literary-legacy-pandemics-200326130141247.html

Ute Lotz-Heumann, University of Arizona

In early April, writer Jen Miller urged New York Times readers to start a coronavirus diary.

“Who knows,” she wrote, “maybe one day your diary will provide a valuable window into this period.”

During a different pandemic, one 17th-century British naval administrator named Samuel Pepys did just that. He fastidiously kept a diary from 1660 to 1669 – a period of time that included a severe outbreak of the bubonic plague in London. Epidemics have always haunted humans, but rarely do we get such a detailed glimpse into one person’s life during a crisis from so long ago.

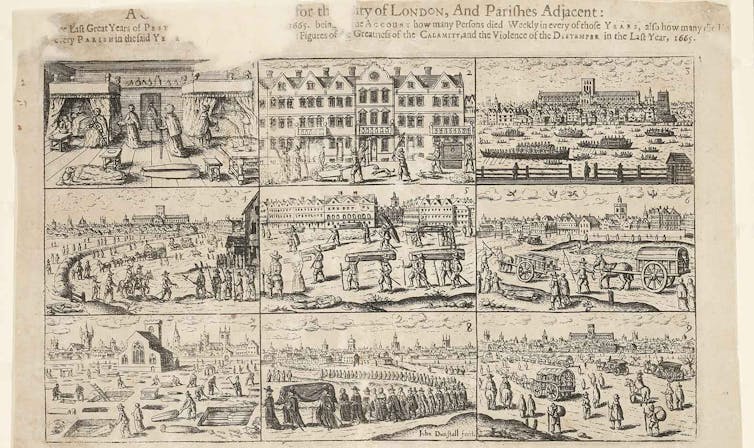

There were no Zoom meetings, drive-through testing or ventilators in 17th-century London. But Pepys’ diary reveals that there were some striking resemblances in how people responded to the pandemic.

For Pepys and the inhabitants of London, there was no way of knowing whether an outbreak of the plague that occurred in the parish of St. Giles, a poor area outside the city walls, in late 1664 and early 1665 would become an epidemic.

The plague first entered Pepys’ consciousness enough to warrant a diary entry on April 30, 1665: “Great fears of the Sickenesse here in the City,” he wrote, “it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all.”

Pepys continued to live his life normally until the beginning of June, when, for the first time, he saw houses “shut up” – the term his contemporaries used for quarantine – with his own eyes, “marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ writ there.” After this, Pepys became increasingly troubled by the outbreak.

He soon observed corpses being taken to their burial in the streets, and a number of his acquaintances died, including his own physician.

By mid-August, he had drawn up his will, writing, “that I shall be in much better state of soul, I hope, if it should please the Lord to call me away this sickly time.” Later that month, he wrote of deserted streets; the pedestrians he encountered were “walking like people that had taken leave of the world.”

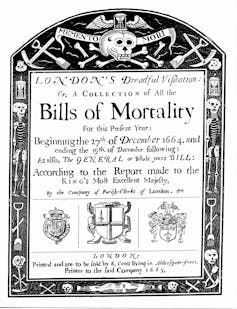

In London, the Company of Parish Clerks printed “bills of mortality,” the weekly tallies of burials.

Because these lists noted London’s burials – not deaths – they undoubtedly undercounted the dead. Just as we follow these numbers closely today, Pepys documented the growing number of plague victims in his diary.

At the end of August, he cited the bill of mortality as having recorded 6,102 victims of the plague, but feared “that the true number of the dead this week is near 10,000,” mostly because the victims among the urban poor weren’t counted. A week later, he noted the official number of 6,978 in one week, “a most dreadfull Number.”

By mid-September, all attempts to control the plague were failing. Quarantines were not being enforced, and people gathered in places like the Royal Exchange. Social distancing, in short, was not happening.

He was equally alarmed by people attending funerals in spite of official orders. Although plague victims were supposed to be interred at night, this system broke down as well, and Pepys griped that burials were taking place “in broad daylight.”

There are few known effective treatment options for COVID-19. Medical and scientific research need time, but people hit hard by the virus are willing to try anything. Fraudulent treatments, from teas and colloidal silver, to cognac and cow urine, have been floated.

Although Pepys lived during the Scientific Revolution, nobody in the 17th century knew that the Yersinia pestis bacterium carried by fleas caused the plague. Instead, the era’s scientists theorized that the plague was spreading through miasma, or “bad air” created by rotting organic matter and identifiable by its foul smell. Some of the most popular measures to combat the plague involved purifying the air by smoking tobacco or by holding herbs and spices in front of one’s nose.

Tobacco was the first remedy that Pepys sought during the plague outbreak. In early June, seeing shut-up houses “put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll-tobacco to smell … and chaw.” Later, in July, a noble patroness gave him “a bottle of plague-water” – a medicine made from various herbs. But he wasn’t sure whether any of this was effective. Having participated in a coffeehouse discussion about “the plague growing upon us in this town and remedies against it,” he could only conclude that “some saying one thing, some another.”

During the outbreak, Pepys was also very concerned with his frame of mind; he constantly mentioned that he was trying to be in good spirits. This was not only an attempt to “not let it get to him” – as we might say today – but also informed by the medical theory of the era, which claimed that an imbalance of the so-called humors in the body – blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm – led to disease.

Melancholy – which, according to doctors, resulted from an excess of black bile – could be dangerous to one’s health, so Pepys sought to suppress negative emotions; on Sept. 14, for example, he wrote that hearing about dead friends and acquaintances “doth put me into great apprehensions of melancholy. … But I put off the thoughts of sadness as much as I can.”

Humans are social animals and thrive on interaction, so it’s no surprise that so many have found social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic challenging. It can require constant risk assessment: How close is too close? How can we avoid infection and keep our loved ones safe, while also staying sane? What should we do when someone in our house develops a cough?

During the plague, this sort of paranoia also abounded. Pepys found that when he left London and entered other towns, the townspeople became visibly nervous about visitors.

“They are afeared of us that come to them,” he wrote in mid-July, “insomuch that I am troubled at it.”

Pepys succumbed to paranoia himself: In late July, his servant Will suddenly developed a headache. Fearing that his entire house would be shut up if a servant came down with the plague, Pepys mobilized all his other servants to get Will out of the house as quickly as possible. It turned out that Will didn’t have the plague, and he returned the next day.

In early September, Pepys refrained from wearing a wig he bought in an area of London that was a hotspot of the disease, and he wondered whether other people would also fear wearing wigs because they could potentially be made of the hair of plague victims.

And yet he was willing to risk his health to meet certain needs; by early October, he visited his mistress without any regard for the danger: “round about and next door on every side is the plague, but I did not value it but there did what I could con ella.”

Just as people around the world eagerly wait for a falling death toll as a sign of the pandemic letting up, so did Pepys derive hope – and perhaps the impetus to see his mistress – from the first decline in deaths in mid-September. A week later, he noted a substantial decline of more than 1,800.

Let’s hope that, like Pepys, we’ll soon see some light at the end of the tunnel.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Ute Lotz-Heumann, Heiko A. Oberman Professor of Late Medieval and Reformation History, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at how public libraries are responding to the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/notes/2020/03/public-libraries-novel-response-to-a-novel-virus/609058/

Paul Yachnin, McGill University

Shakespeare lived his life in plague-time. He was born in April 1564, a few months before an outbreak of bubonic plague swept across England and killed a quarter of the people in his hometown.

Death by plague was excruciating to suffer and ghastly to see. Ignorance about how disease spread could make plague seem like a punishment from an angry God or like the shattering of the whole world.

Plague laid waste to England and especially to the capital repeatedly during Shakespeare’s professional life — in 1592, again in 1603, and in 1606 and 1609.

Whenever deaths from the disease exceeded thirty per week, the London authorities closed the playhouses. Through the first decade of the new century, the playhouses must have been closed as often as they were open.

Epidemic disease was a feature of Shakespeare’s life. The plays he created often grew from an awareness about how precarious life can be in the face of contagion and social breakdown.

Except for Romeo and Juliet, plague is not in the action of Shakespeare’s plays, but it is everywhere in the language and in the ways the plays think about life. Olivia in Twelfth Night feels the burgeoning of love as if it were the onset of disease. “Even so quickly may one catch the plague,” she says.

In Romeo and Juliet, the letter about Juliet’s plan to pretend to have died does not reach Romeo because the messenger is forced into quarantine before he can complete his mission.

It is a fatal plot twist: Romeo kills himself in the tomb where his beloved lies seemingly dead. When Juliet wakes and finds Romeo dead, she kills herself too.

The darkest of the tragedies, King Lear, represents a sick world at the end of its days. “Thou art a boil,” Lear says to his daughter, Goneril, “A plague sore … In my corrupted blood.”

Those few characters left alive at the end, standing bereft in the midst of a shattered world, seem not unlike how many of us feel now in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s good to know that we — I mean all of us across time — might find ourselves sometimes in “deep mire, where there is no standing,” in “deep waters, where the floods overflow me,” in the words of the biblical psalmist.

But Shakespeare can also show us a better way. Following the 1609 plague, Shakespeare gave his audience a strange, beautiful restorative tragicomedy called Cymbeline. The international Cymbeline Anthropocene Project, led by Randall Martin at the University of New Brunswick, and including theatre companies from Australia to Kazakhstan, envisions the play as a way to consider how to restore a liveable world today.

Cymbeline took Shakespeare’s playgoers into a world without plague, but one filled with the dangers of infection nonetheless. The play’s evil queen experiments with poisons on cats and dogs. She even sets out to poison her stepdaughter, the princess Imogen.

Infection also takes the form of slander, which passes virus-like from mouth to mouth. The principal target again is Imogen, framed by wicked lies against her virtue by a man named Giacomo that her banished husband, Posthumus, hears. From Italy, Posthumus sends orders to his man in Britain to assassinate his wife.

The world of the play is also defiled by evil-eye magic, where seeing something abominable can sicken people. The good doctor Cornelius counsels the queen that experimenting with poisons will “make hard your heart.”

“… Seeing these effects will be

Both noisome and infectious.”

Even being seen by antagonistic people can be toxic. When Imogen is saying farewell to her husband, she is mindful of the threat of other people’s evil looking, saying:

“You must be gone,

And I shall here abide the hourly shot

Of angry eyes.”

Shakespeare leads us from this courtly wasteland toward the renewal of a healthy world. It is an arduous pilgrimage. Imogen flees the court and finds her way into the mountains of ancient Wales. King Arthur, the mythical founder of Britain, was believed to be Welsh, so Imogen is going back to nature and also to where her family bloodline and the nation itself began.

Indeed her brothers, stolen from court in early childhood, have been raised in the wilds of Wales. She reunites with them, though neither she nor they know yet that they are the lost British princes.

The play seems to be gathering toward a resolution at this juncture, but there is still a long journey. Imogen must first survive, so to speak, her own death and the death of her husband.

She swallows what she thinks is medicine, not knowing it’s poison from the queen. Her brothers find her lifeless body and lay her beside the headless corpse of the villain Cloten.

Thanks to the good doctor, who substituted a sleeping potion for the queen’s poison, Imogen doesn’t die. She wakes from a death-like sleep to find herself beside what she thinks is the body of her husband.

Yet, with nothing to live for, Imogen still goes on living. Her embrace of bare life itself is the ground of wisdom and the step she must take to reach toward her own and others’ happiness.

She comes at last to a gathering of all the characters. Giacomo confesses how he lied about her. A parade of truth-telling cleanses the world of slander. Posthumus, who believes that Imogen has been killed on his order, confesses and begs for death. She, in disguise, runs to embrace him, but in his despair he strikes her down. It is as if she must die again. When she recovers consciousness, and it’s clear she will survive, and they are reunited, Imogen says:

“Why did you throw your wedded lady from you?

Think that you are upon a rock, and now

Throw me again.”

Posthumus replies:

“Hang there like fruit, my soul,

Till the tree die.”

Imogen and Posthumus have learned that we come together in love only when the roots of our being grow deep into the natural world and only when we gain a full awareness that, in the course of time, we will die.

With that knowledge and in a world cured of poison, slander and the evil eye, the characters are free to look at each other eye to eye. The king himself directs out attention to how Imogen sees and is seen, saying:

“See,

Posthumus anchors upon Imogen,

And she, like harmless lightning, throws her eye

On him, her brothers, me, her master, hitting

Each object with a joy.”

We will continue to need good doctors now to protect us from harm. But we can also follow Imogen through how the experience of total loss can purge our fears, and learn with her how to start the journey back toward a healthy world.![]()

Paul Yachnin, Tomlinson Professor of Shakespeare Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

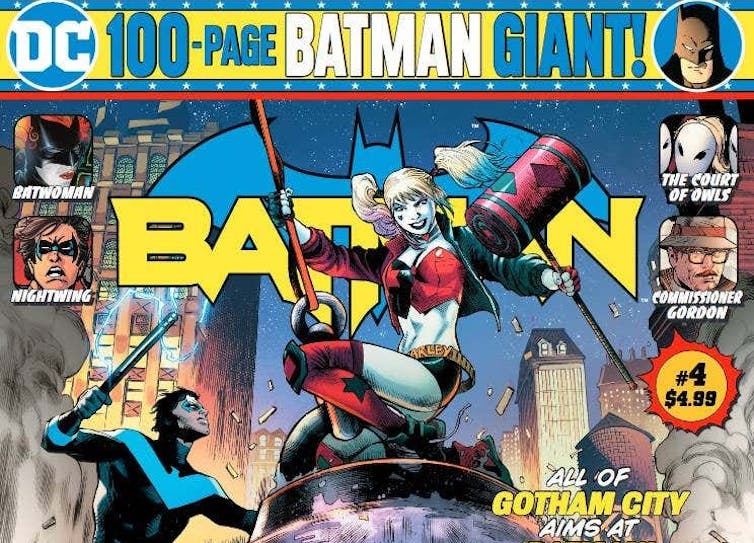

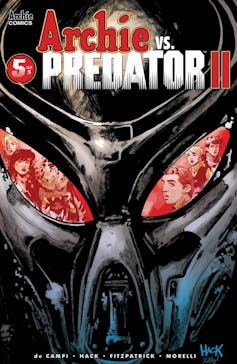

Bart Beaty, University of Calgary

Last week, the producers behind a number of comic book-derived movies and TV shows announced delays for their franchises: release dates for Wonder Woman and Black Widow were pushed ahead, while The Walking Dead announced that COVID-19 had made it impossible for the show to complete work on the current season and that the finale was being delayed.

But what of the comic books that spawned these blockbuster franchises?

On March 23, Steve Geppi, CEO of Diamond Comic Distributors, announced the closing of the distribution system that holds a near-monopoly on the circulation of comic books in North America. He cited a number of problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic: comic retailers can’t service customers, publishing partners are having supply chain issues and shipping is delayed. He wrote his “only logical conclusion is to cease the distribution of new weekly product until there is greater clarity on the progress made toward stemming the spread of this disease.”

New Comics Day has occurred every Wednesday since the creation of the direct market in the 1970s, as die-hard fans rush to buy new books before spoilers pop up online.

But no longer: This week, for the first time in more than 80 years, no new comic books will ship to shops, and production is on hold into the foreseeable future. No previous global event — not the Second World War, not 9/11 — has previously shuttered the comic book industry.

To understand how this single decision could transform the operations of comic book publishers owned by Disney (Marvel Comics) and AT&T (DC Comics), among dozens of others, as well as comic production, consumption and culture, one needs to understand how the status of the comic book has shifted over the past century.

As Jean-Paul Gabilliet, professor of North American studies at Université Bordeaux demonstrates, the comic book form emerged in the 1930s as a promotional giveaway for department stores and gas stations before it migrated to the newsstand as a part of the larger magazine industry.

Despite some fits and starts, the format took off based the success of Superman, created in spring 1938, and the many imitation superheroes his popularity spawned as comic books became a staple of the newsstand. Circulation grew during the war, and exploded shortly after as new publishers initiated new genres like crime, romance and horror comic books.

By 1952, the peak year for comic book sales in the United States, comic books were a formidable cultural presence. But the rise of television, changes to the magazine distribution system and criticisms of the industry by public figures led to an industry-wide collapse of sales. Comic books limped through the 1960s as a cheap disposable form of entertainment for children, found on magazine racks that catered to parents.

By the 1970s, the American comic book had lost its status as a mass medium. At the same time, a rapidly growing network of used comic-book dealers began to spring up at flea markets, conventions, bookstores and eventually specialty stores that catered to a devoted set of comic collectors. The growing fan network presented a life raft to the industry.

The turning point, as American writer and reporter Dan Gearino points out in his history of comic book stores, came in 1972 when a convention organizer named Phil Seuling convinced the major publishers to wholesale new issues to him on a non-returnable basis.

This appealed to the publishers, who were accustomed to routinely over-printing comic books by the hundreds of thousands to supply the inefficient system of mom-and-pop corner stores that retailed their work. Seuling’s model shifted risk from the publisher to the retailer, who ordered product on a non-returnable basis, but it facilitated the growth of a network of thousands of comic book shops across North America.

For more than two decades, comic book shops were supplied by a network of regional wholesale distributors that served specific geographic regions based on the location of their warehouses. This changed at the end of 1994 when Marvel Comics bought Heroes World, the third largest distributor.

American writer Sean Howe’s history of Marvel Comics details how, in July 1995, the company made their new subsidiary the exclusive supplier of their market-leading product, reducing income at the other distributors by a third. A scramble ensued, with Geppi’s Diamond securing the rights to DC Comics and Image Comics, the next two largest publishers after Marvel. Other publishers quickly fell in line, signing exclusive deals with Diamond and bankrupting the regional distributors.

When Heroes World proved incapable of supporting Marvel’s needs, the company folded in 1996 and Marvel joined forces with Diamond, the only other distributor still standing. That same year, the Bill Clinton government began investigating Diamond as a monopoly. But the government dismissed the case in 2000, finding that the new company was not monopolistic because comic books were only a small part of the overall publishing industry.

The situation remained largely unchanged for more than 20 years. Diamond is the exclusive dealer of comic books to the a network of thousands of comic book stores who have continued to order on a non-returnable basis. Until now.

The consequences of Diamond’s decision are immediate and wide-reaching. In closing their warehouses to new product, publishers have alerted printers to stop. Comic book freelancers recently began tweeting they’d received “pencils down” messages from publishers curtailing production.

Communication to comic book retailers, creative personnel and fans has been haphazard as the large publishers scramble to plan for an uncertain future. Many are concerned about the growing digital footprint of comic book publishers.

Since 2011, most comic books have been released to comic book stores and in electronic format to consumers through platforms like Comixology (a subsidiary of Amazon) on the same day.

With a protracted closure of the distribution system, publishers like Marvel and DC could continue to move forward with electronic sales, which would inevitably bolster that end of their business at the expense of their retail partners. Archie Comics has announced that they will release some April titles digitally.

If several months passed with electronic sales but no physical comic book sales, it’s uncertain that those printed books would ever find an audience. An extended pause by the biggest publishers, on the other hand, would undoubtedly spur comics creators to pursue new projects either online or through the book trade.

This could accelerate a shift away from comic collectors’ habitual buying that take place comic shops as establishments that foster unique social relations, as described by Benjamin Woo, associate professor of communication and media studies at Carleton University.

While comic books sales proved remarkably resilient during the 2008 financial crisis, if the current situation breaks readers’ buying habits for a few months, they might never return in the same way.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published on March 30, 2020. The earlier story said Diamond Comic Distributors made an announcement March 24 instead of March 23.![]()

Bart Beaty, Professor of English, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dystopian fiction seems so alluring during the coronavirus pandemic. As we eagerly await a return to normalcy, many say we can aspire to do better — whether we are talking about wealth distribution or global warming. What dystopian fiction does especially well is to show how we can do more than simply repeat.

Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018), an adaptation of Ernest Cline’s bestselling novel of the same title (2011), is a case in point. Set in 2045 in the city of Columbus, Ohio, it speaks of a world that has weathered corn syrup droughts and bandit riots.

People have now resorted to outliving rather than fixing the world’s problems. Accordingly, a virtual reality game known as the OASIS has become a refuge for many, including the central protagonist Wade Watts (Tye Sheridan).

Small wonder that the OASIS is so appealing. Within its walls, Spielberg pays homage to many aspects of popular culture. The video game Minecraft (2009) is a possible setting, and throughout the film, viewers watch Chucky, the Iron Giant and Mechagodzilla in battle.

Entire plot sequences incorporate existing popular characters, music and stories. In a nod to Superman, Watts dons Clark Kent glasses to conceal his identity. And in a sequence worthy of the film’s 2019 Academy Award nomination for Achievement in Visual Effects, Watts and his romantic interest Samantha Cook (Olivia Cooke) dance to the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” (1977).

The central conflict in Ready Player One arises when James Halliday (Mark Rylance), one of the OASIS’s creators, dies and leaves behind a seemingly impossible quest. The prize is his extensive fortune and total control over the OASIS. Watts’ competitors include the Innovative Online Industries (IOI), a loyalty centre that seeks to take over the OASIS.

The IOI is shown to be exploitative. Samantha’s father, we learn, borrowed gaming gear, built up debt and moved into the IOI in hopes to repay it, only to fall ill and die. Samantha stands to follow his example and her debt has already exceeded 23,000 credits.

What distinguishes the film — and its source material — is its exploration of how we negotiate with a social order rife with inequalities. This theme is particularly timely: COVID-19 has made apparent, for instance, the links between inequality and public health.

In the novel, the IOI’s corporate police arrest Wade, and he is marshalled out of his apartment complex and into a transport truck. As the vehicle moves, he peers out of its window and absorbs the changes that have befallen the world:

“A thick film of neglect still covered everything in sight …. The number of homeless people seemed to have increased drastically. Tents and cardboard shelters lined the streets, and the public parks I saw seemed to have been converted into refugee camps.”

The key term here is neglect. Wade is not alone in having forsaken the world. The virtual universe of the OASIS may have provided a convenient refuge. But choosing to escape the world’s realities has contributed to a dramatic rise in social and economic inequalities.

Both Cline’s novel and Spielberg’s film trace Watts’ growth into a better global citizen and his reconnection to the real world, so that his triumph can entail more than the regeneration of a flawed system. Spielberg expands on the novel by exploring what Watts does with his new-found wealth and power.

Watts shares his gains with his friends and together they take constructive steps towards improving both the OASIS and the wider world: they employ Halliday’s friend Ogden (Simon Pegg) as a non-exclusive consultant. They also ban loyalty centres from accessing the OASIS and switch off the virtual world on Tuesdays and Thursdays to encourage people to spend more time in the real world.

All of these actions seem commendable and they reveal how different Watts and his friends are to Halliday. Yet the film also exposes paradoxes inherent in fixing a broken system with its very tools.

In a recent article on the novel that I wrote with James Munday, a mathematics and statistics undergraduate student, we argue that any major change Wade makes to the OASIS, such as closing it for extended periods, demands that he and his fellow shareholders take on a substantial loss: their power is contingent upon the OASIS after all. But Wade seeks a more selfless and heroic win: creating a system that answers the needs of the many.

What Spielberg does especially well is to show the importance of imagining the world in new ways — and the temptation and problems with rebuilding a broken one in its own image.

In this, Spielberg harks back to a long genealogy of dystopian fiction, a genre invested in world building. The problems that Watts faces are anticipated, for instance, in George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), where we find an exploitative social system replaced by one even more so because it is more efficient.

Recently, Gregory Claeys provided us with an interdisciplinary map of the genre in his illuminating study Dystopia: A Natural History. In a short essay, he draws connections between the fears that we feel in these times of uncertainty to the genre’s central concerns.

As we collectively meditate on the world’s problems, why not imagine better worlds?![]()

Tom Ue, Adjunct Professor, Department of English, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Elaine Reese, University of Otago

Humans are innately social creatures. But as we stay home to limit the spread of COVID-19, video calls only go so far to satisfy our need for connection.

The good news is the relationships we have with fictional characters from books, TV shows, movies, and video games – called parasocial relationships – serve many of the same functions as our friendships with real people, without the infection risks.

Read more:

Say what? How to improve virtual catch-ups, book groups and wine nights

Some of us already spend vast swathes of time with our heads in fictional worlds.

Psychologist and novelist Jennifer Lynn Barnes estimated that across the globe, people have collectively spent 235,000 years engaging with Harry Potter books and movies alone. And that was a conservative estimate, based on a reading speed of three hours per book and no rereading of books or rewatching of movies.

This human predilection for becoming attached to fictional characters is lifelong, or at least from the time toddlers begin to engage in pretend play. About half of all children create an imaginary friend (think comic strip Calvin’s tiger pal Hobbes).

Preschool children often form attachments to media characters and believe these parasocial friendships are reciprocal — asserting that the character (even an animated one) can hear what they say and know what they feel.

Older children and adults, of course, know that book and TV characters do not actually exist. But our knowledge of that reality doesn’t stop us from feeling these relationships are real, or that they could be reciprocal.

When we finish a beloved book or television series and continue to think about what the characters will do next, or what they could have done differently, we are having a parasocial interaction. Often, we entertain these thoughts and feelings to cope with the sadness — even grief — that we feel at the end of a book or series.

The still lively Game of Thrones discussion threads or social media reaction to the death of Patrick on Offspring a few years back show many people experience this.

Some people sustain these relationships by writing new adventures in the form of fan fiction for their favourite characters after a popular series has ended. Not surprisingly, Harry Potter is one of the most popular fanfic topics. And steamy blockbuster Fifty Shades of Grey began as fan fiction for the Twilight series.

So, imaginary friendships are common even among adults. But are they good for us? Or are they a sign we’re losing our grip on reality?

The evidence so far shows these imaginary friendships are a sign of well-being, not dysfunction, and that they can be good for us in many of the same ways that real friendships are good for us. Young children with imaginary friends show more creativity in their storytelling, and higher levels of empathy compared to children without imaginary friends. Older children who create whole imaginary worlds (called paracosms) are more creative in dealing with social situations, and may be better problem-solvers when faced with a stressful event.

As adults, we can turn to parasocial relationships with fictional characters to feel less lonely and boost our mood when we’re feeling low.

As a bonus, reading fiction, watching high-quality television shows, and playing pro-social video games have all been shown to boost empathy and may decrease prejudice.

We need our fictional friends more than ever right now as we endure weeks in isolation. When we do venture outside for a walk or to go the supermarket and someone avoids us, it feels like social rejection, even though we know physical distancing is recommended. Engaging with familiar TV or book characters is one way to rejuvenate our sense of connection.

Plus, parasocial relationships are enjoyable and, as American literature professor Patricia Meyer Spacks noted in On Rereading, revisiting fictional friends might tell us more about ourselves than the book.

So cuddle up on the couch in your comfiest clothes and devote some time to your fictional friendships. Reread an old favourite – even one from your childhood. Revisiting a familiar fictional world creates a sense of nostalgia, which is another way to feel less lonely and bored.

Read more:

Couch culture – six months’ worth of expert picks for what to watch, read and listen to in isolation

Take turns reading the Harry Potter series aloud with your family or housemates, or watch a TV series together and bond over which characters you love the most. (I recommend Gilmore Girls for all mothers marooned with teenage daughters.)

Fostering fictional friendships together can strengthen real-life relationships. So as we stay home and save lives, we can be cementing the familial and parasocial relationships that will shape us – and our children – for life.![]()

Elaine Reese, Professor of Psychology, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on an emergency fund that has been set up for author during the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/20/this-is-a-scary-time-coronavirus-emergency-fund-set-up-for-authors

The link below is to an article that reports on how Italy has been finding some hope during the coronavirus pandemic by turning to ‘The Betrothed,’ by Alessandro Manzoni.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/italys-answer-to-coronavirus-is-a-classic-published-almost-200-years-ago/

You must be logged in to post a comment.