The link below is to a very helpful article on the cleaning and maintenance of books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/03/28/how-to-clean-books/

The link below is to a very helpful article on the cleaning and maintenance of books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/03/28/how-to-clean-books/

The link below is to an article that offers a number of suggestions on how to read more books.

For more visit:

https://hbr.org/2019/04/8-ways-to-read-the-books-you-wish-you-had-time-for

The link below is to an article that takes a look at books about books.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at various modes of transport – planes, trains, ships, etc, and their place in books.

For more visit:

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/04/10/a-readers-guide-to-planes-trains-automobiles/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the history of product placement in books.

For more visit:

https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/4/8/18250031/book-product-placement-bulgar-connection-click-fic-shopfiction

The link below is to an article that considers identities tied up in books.

For more visit:

https://electricliterature.com/liking-books-is-not-a-personality/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at finding DNA in old books.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/02/dna-books-artifacts/582814/

The link below is to an article that looks at whether paperbacks need to be upgraded as they age.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2019/02/15/do-beloved-paperbacks-need-an-upgrade/

Sally O’Reilly, The Open University

The way women are portrayed is changing. In film, The Favourite has won numerous awards and features three women, variously wild and untameable, as joint protagonists. Other movies such as The Wife and Can You Ever Forgive Me? show older or unlovely women as sympathetic leads. Brava! But what’s happening in fiction? What are readers looking for in their modern, made-up women?

In this period of widening gender equality, it seems the time is right for new portrayals of women in fiction. Readers are diverse, and want many different things, and various female “archetypes” have existed since storytelling began. Early tales included murderesses and proxy witches such as the Greek figure Medea and Grendel’s mother – who is nameless – from the Old English poem Beowulf.

There were deceiving femme fatales, such as the Sirens who lured sailors to shipwreck, tragic mistresses, including Dido and Cleopatra and poor, resourceful girls like Gretel in traditional fairy-tales.

These enduring archetypes have been customised and reimagined by each succeeding generation. Chaucer’s Wife of Bath is full of worldly wisdom and Shakespeare presented women who were wily and devious like Portia and Lady Macbeth as well as tricked and deceived like Juliet and Desdemona.

Victorian heroines like George Eliot’s Dorothea Brooke claimed their right to passion and equality – and in the 20th century female characters engaged with the world of work as well as matters of the heart, battling for self-determination. The eponymous heroine of Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is one example, setting out to impose her will on her impressionable students, though she is ultimately betrayed.

So where do we find ourselves now? One notable characteristic of the modern heroine is that her flaws are not only centre stage, they are celebrated. Jane Austen wondered if anyone but herself would like domineering Emma Woodhouse – but now every heroine worth her salt has as many vices as virtues. Women behaving badly fill the pages of books in every genre – from Katniss Everdene, the rebellious heroine of Suzannne Collins’ The Hunger Games to Frances Wray and Lilian Barber, the unlikely conspirators in Sarah Waters’ page-turning novel The Paying Guests.

There is also a recognition that female experience is as universal as male experience. The heroines of contemporary fiction reflect the rich diversity of female lives. Examples include Hortense Roberts, one of the main characters in Andrea Levy’s seminal novel Small Island who finds tenderness in her bleak new homeland, and Elizabeth Strout’s astonishing Olive Kitteridge, whose true complexity is revealed in a narrative that spans decades. Their everyday experiences are compelling and heartrending.

Genres are blending and heroines are complicated. They are morally ambiguous and their behaviour is unpredictable. The doomed mistress is fighting back and taking on the characteristics of the proxy witch. This is demonstrated by the typical heroine of the new crime sub-genre domestic noir which focuses on women’s experience and emotions in the home and workplace. She may find herself married to the modern equivalent of Bluebeard, but he is unlikely to get away with murder. This is exemplified in novels like Gone Girl – Amy Dunne outsmarts her husband and excels in trickery, cunningly creating mantraps while seeming to be the perfect wife.

Publishing’s latest passion is for redemptive, feel-good fiction, known as “up-lit”, and this also reinterprets existing tropes. Gail Honeyman’s lonely Eleanor Oliphant hits the vodka behind closed doors and attempts to conceal her dysfunctionality and traumatic childhood from the world, but is stronger and more able to grow than we first realise. One of the reasons for Eleanor’s wide appeal may be that she springs from a line of literary heroines – that of the spirited outsider.

Honeyman draws parallels between Eleanor and Jane Eyre, another abandoned child who finds her own path. Readers are engaged not only by Eleanor’s predicament, but by her determination to transcend disaster. Her most recent antecedent is Helen Fielding’s Chardonnay-swilling Bridget Jones, who is herself the direct descendant of Jane Austen’s best-loved heroine, Elizabeth Bennet.

Women who make their own rules are selling well in literary fiction too. In Conversations with Friends, Sally Rooney’s young Bohemians Frances and Bobbi are brimming with anarchic attitude, sharing “a contempt for the cultish pursuit of male physical dominance” and luxuriating in “shallow misery”. They lead unapologetically experimental lives, creating ripples of sexual confusion.

Following the various cases of male bullying and sexual harassment that have hit the headlines, it seems that fictional heroines reflect a mood of noncompliance with the world that men have organised. The 21st-century heroine may be scarred, imperfect or absurd. True love may be on the cards, but so might illicit sex. And while she may change in the course of the narrative, revealing strengths and strategies that surprise us, conformity is optional. Here’s to the good/bad heroine, long may she remain unredeemed.![]()

Sally O’Reilly, Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

shutterstock

Amy Wigelsworth, Sheffield Hallam University

An emerging genre of fiction in France is providing an unlikely brand of escapism. Growing numbers of French writers are choosing work as their subject matter – and it seems that readers can’t get enough of their novels.

The prix du roman d’entreprise et du travail, the French prize for the best business or work-related novel, is testament to the sustained popularity of workplace fiction across the Channel. The prize has been awarded annually since 2009, and this year’s winner will be announced at the Ministry of Employment in Paris on March 14.

Place de la Médiation, the body which set up the prize, is a training organisation specialising in mediation, the prevention of psychosocial risks, and quality of life at work. Co-organiser Technologia is a work-related risk prevention consultancy, which helps companies to evaluate health, safety and organisational issues.

The novels shortlisted for the prize in the past ten years reflect a broad range of jobs and sectors and a whole gamut of experiences. The texts clearly strike a chord with French readers, but English translations of these novels suggest many of the themes broached resonate in Anglo-Saxon culture too.

The prize certainly seeks to acknowledge a pre-existing literary interest in the theme of work. This is unsurprising in the wake of the global financial crisis and the changes and challenges this has brought. But the organisers also express a desire to actively mobilise fiction in a bid to help chart the often choppy waters of the modern workplace:

Through the power of fiction, [we] want to put the human back at the heart of business, to show the possibilities of a good quality professional life, and to relaunch social dialogue by bringing together in the [prize] jury all the social actors and specialists of the business world.

What better way to delve into this unusual genre than by reading some of the previous prize winners. Below are five books to get you started.

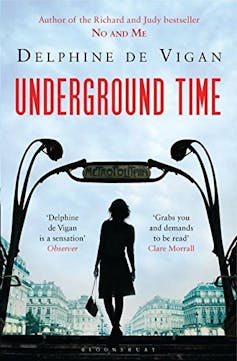

The first prize was awarded to Delphine de Vignan for Les heures souterraines. In this novel, the paths of a bullied marketing executive and a beleaguered on-call doctor converge and intersect as they traverse Paris over the course of a working day. A television adaptation followed, and an English translation was published by Bloomsbury in 2011. Work-related journeys and the underground as a symbol for the hidden or unseen side of working life have proved enduring themes, picked up by several subsequent winners.

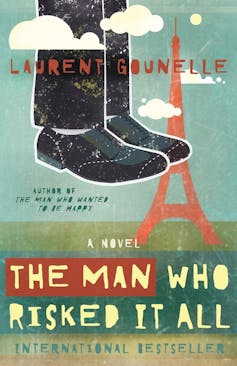

Laurent Gounelle’s Dieu voyage toujours incognito, winner of the 2011 prize, takes us from the depths of the underground to the top of the Eiffel Tour, where Alan Greenmor’s suicide attempt is interrupted by a mysterious stranger. Yves promises to teach him the secrets to happiness and success if Alan agrees to do whatever he asks. This intriguing premise caught the attention of self-help, inspirational and transformational book publisher Hay House, whose translation appeared in 2014.

Read more:

Five books by women, about women, for everyone

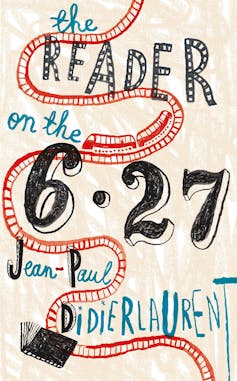

Le liseur du 6h27 by Jean-Paul Didierlaurent, the 2015 winner, tells the story of a reluctant book-pulping machine operative. Each day, Ghislain Vignolles rescues a few random pages from destruction, to read aloud to his fellow-commuters in the morning train. The novel crystallises the fraught relationship between intellectual life and manual work.

It also illustrates the tension between culture and commerce, arguably at its most pronounced in France, where cultural policy has traditionally insisted on the distinction between cultural artefacts and commercial products. The Independent review of the English translation describes the book as “a delightful tale about the kinship of reading”.

Slimane Kader took to the belly of a Caribbean cruise ship to research Avec vue sous la mer, which claimed the 2016 prize. His hilarious account of life as “joker”, or general dogsbody, is characterised by an amusing mishmash of cultural references: “I’m dreaming of The Love Boat, but getting a remake of Les Misérables” the narrator quips. The use of “verlan” – a suburban dialect in which syllables are reversed to create new words – underlines the topsy-turvy feel.

Unfortunately, there’s no English version as yet – I imagine the quickfire language play would challenge even the most adept of translators. But translation would help confirm the compelling literary voice Kader has given to an otherwise invisible group.

Catherine Poulain’s Le grand marin, the 2017 winner, is a rather more earnest account of work at sea. The author draws on her own experiences to recount narrator Lili’s travails in the male-dominated world of Alaskan fishing.

Le grand marin (the great sailor) is ostensibly the nickname Lili gives to her seafaring lover. The relationship is something of a red herring though, as the overriding passion in this novel is work. But the English title perhaps does Lili a disservice – she is less a floundering Woman at Sea, and more the true grand marin of the original.

This year’s shortlist includes the story of a forgotten employee left to his own devices when his company is restructured, a professional fall from grace in the wake of the Bataclan terrorist attack, and a second novel from Poulain, with seasonal work in Provence the backdrop this time.

The common draw, as in previous years –- and somewhat ironically, given the subject matter –- is escapism. We are afforded either a tantalising glimpse into the working lives of others, or else a fresh perspective on our own. English readers will be equally fascinated by French details and universal themes – and translators’ pens are sure to be poised.![]()

Amy Wigelsworth, Senior Lecturer in French, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.