The link below is to an article that takes a look at the importance of getting food right in fiction.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-importance-of-getting-food-right-in-fiction/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the importance of getting food right in fiction.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-importance-of-getting-food-right-in-fiction/

The link below is to an article that looks at buying ebook readers on Ebay and provides a useful warning on batteries.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/electronic-readers/do-not-buy-an-old-e-reader-on-ebay

Caitlyn Forster, University of Sydney

People may think of comics and science as worlds apart, but they have been cross-pollinating each other in more than ways than one.

Many classic comic book characters are inspired by biology such as Spider-Man, Ant-Man and Poison Ivy. And they can act as educational tools to gain some fun facts about the natural world.

Some superheroes have scientific careers alongside their alter egos. For example, Marvel’s The Unstoppable Wasp is a teenage scientist. And DC Comics’ super-villain Poison Ivy is a botanist who saved honey bees from colony collapse.

Superheroes have also crept into the world of taxonomy, with animals being named after famous comic book characters. These include a robber fly named after the Marvel character Deadpool (whose mask looks like the markings on the fly’s back) and a fish after Marvel hero Black Panther.

Read more:

From superheroes to the clitoris: 5 scientists tell the stories behind these species names

I am a PhD student researching bee behaviour and I have spent most of my university life working at a comic book store. Here’s how superheroes could be used to make biology, and other types of science, more intriguing to school students.

Reading has a range of benefits, from improved vocabulary, comprehension and mathematics skills, to increased empathy and creativity.

While it’s hard to directly prove the advantages of comics over other forms of reading, they can be engaging, easy to understand learning tools.

Comics have similar benefits to classic textbooks in terms of understanding course content. But they can be more captivating.

A study of 114 business students showed they preferred graphic novels over classic textbooks for learning course content.

In another study in the United States, college biology students were given either a textbook or a graphic novel — Optical Allusions by scientist Jay Hosler, that follows a character discovering the science of vision — as supplementary reading for their biology course.

Both groups of students showed similar increases in course knowledge, but students who were given the graphic novel showed an increased interest in the course.

So, comics can be used to engage students, especially those who aren’t very interested in science.

Educational comics such as the Science Comics series, Jay Hosler’s The Way of the Hive and Abby Howard’s Earth Before Us series frequently have a narrative structure with a story consisting of a beginning, middle and resolution.

Students often find information inside storytelling easier to comprehend than when it’s provided matter-of-factly, such as in textbooks. As readers follow a story, they can use key information they have learnt along the way to understand and interpret the resolution.

In science-related comic books, as the story unfolds, scientific concepts are often sprinkled in along the way. For example, Science Comics: Bats, follows a bat going through a rehabilitation clinic while suffering from a broken wing. The reader learns about different bat species and their ecology on this journey.

Comics also have the advantage of permanance, meaning students can read, revisit and understand panels at their own pace.

Many science comics, including Optical Allusions, are written by scientists, allowing for reliable facts.

Using storytelling can also humanise scientists by creating relatable characters throughout comics. Some graphic novels showcase scientific careers and can be a great tool for removing stereotypes of the lab coat wearing scientist. For example, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wick’s graphic novels Primates and Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier showcase female scientists in labs, the field and even space.

The Marvel series’ Unstoppable Wasp also includes interviews with female scientists at the end of each issue.

Imagery combined with an easy to follow narrative structure can also give a look into worlds that may otherwise be hard to visualise. For example, Science Comics: Plagues, and the Manga series, Cells at Work!, are told from the point of view of microbes and cells in the body.

Imagery can also show life cycles of animals that are potentially dangerous, or difficult to encounter, such as a honeybee colony, which was visualised through Clan Apis.

The author would like to acknowledge neuroscientist and cartoonist Matteo Farinella, whose advice helped shape this article.![]()

Caitlyn Forster, PhD Candidate, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rachel D. Williams, Simmons University; Christine D’Arpa, Wayne State University, and Noah Lenstra, University of North Carolina – Greensboro

America’s public library workers have adjusted and expanded their services throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to initiating curbside pickup options, they’re doing many things to support their local communities, such as extending free Wi-Fi outside library walls, becoming vaccination sites, hosting drive-through food pantries in library parking lots and establishing virtual programs for all ages, including everything from story times to Zoom sessions on grieving and funerals.

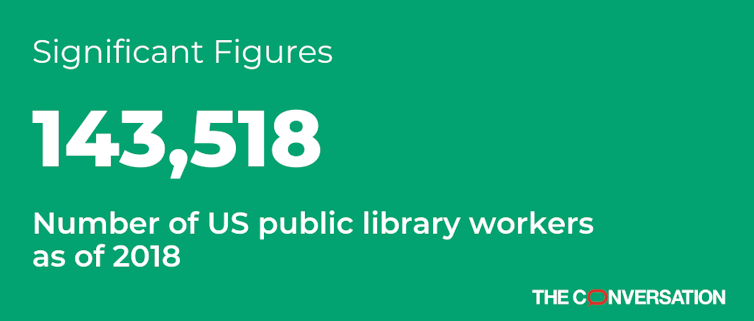

In 2018, there were 143,518 library workers in the United States, according to data collected by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. While newer data isn’t available, the number is probably lower now, and recent history suggests more library jobs may be on the chopping block in the near future.

As library and information science researchers, we are concerned about library worker job insecurity.

During the Great Recession, the economic downturn between late 2007 and mid-2009, thousands of librarians and other library staff lost their jobs. As local governments cut spending on libraries, the size of that workforce shrank to 137,369 in 2012 from 145,499 in 2008.

Many library workers actively supported the recovery from that economic crisis in many creative ways. Some loaned patrons professional attire to wear for job interviews. Others helped local unemployed people gain basic financial literacy and digital skills.

Unfortunately, many of the Great Recession’s job losses were never completely overcome. There were about 2,000 fewer library workers in 2018 than in 2008, at the height of the crisis.

Library workers are again losing their jobs despite the important roles that libraries are playing today. According to preliminary data and news coverage collected by the Tracking Library Layoffs initiative, it’s clear that not all of the library workers furloughed since March 2020, when virtually all U.S. libraries were closed amid lockdowns, have been brought back on staff.

At the same time, many library workers have had to directly engage in person with the public throughout the pandemic, exposing them to health risks.

There are steps the federal government could take to protect the nation’s libraries.

For example, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the Federal Emergency Management Agency recognized libraries among essential services. The federal government has not taken this step so far during the coronavirus pandemic.

Among other things, lacking this designation may have made it more difficult for librarians and other library staff members to get COVID-19 vaccines.

To date, the federal coronavirus relief packages have included a total of about US$250 million to support public libraries. These funds, distributed to state library agencies, amount to approximately $14,304 – about 1.7% of their annual revenue – for each of the nation’s 17,478 library branches and bookmobiles. We suspect that this infusion of cash will fall short of what’s needed to help public libraries and their workers recover from the tumult caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

Rachel D. Williams, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Science, Simmons University; Christine D’Arpa, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Sciences, Wayne State University, and Noah Lenstra, Assistant Professor of Library and Information Science, University of North Carolina – Greensboro

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mary Chapman, University of British Columbia

In March, when a white man targeted and killed eight women in Atlanta, six of whom were Asian, mainstream media and police initially refused to categorize it as a racially motivated hate crime. But for Asian people, across North America and globally, this tragedy was one more episode in a long history of anti-Asian violence.

Over 150 years ago, white settlers in the United States rounded up Chinese merchants and miners and put them onto burning barges, threw them into railway cars and even lynched them. But this story is not limited to the U.S. — early Chinese immigrants were not welcome in Canada either.

Read more:

Asian Americans top target for threats and harassment during pandemic

This is documented in the life and works of Chinese-Canadian author and journalist Edith Eaton (1865-1914). While researching Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton, I discovered numerous accounts of early Canadian anti-Chinese racism in her work.

In Eaton’s memoir Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian, she recalls being called “Chinky, Chinky, Chinaman, yellow-face, pig-tail, rat-eater,” after moving to North America with her family — a white father, Chinese mother and five siblings — in 1872.

Soon after the family’s arrival in Montréal, locals would call out “Chinese!” “Chinoise!” as they walked down the street. Classmates would pull Eaton’s hair, pinch her and refuse to sit beside her.

These taunts and torments were felt deeply by Eaton throughout her life. She wrote:

“I have come from a race on my mother’s side which is said to be the most stolid and insensible to feeling of all races. Yet I look back over the years and see myself so keenly alive to every shade of sorrow and suffering that it is almost a pain to live.”

Eaton published a book of short stories depicting Chinese immigrants’ encounters with racism under the pseudonym “Sui Sin Far” (Cantonese for narcissus). And her advocacy was appreciated by Chinese people in Montréal who erected a memorial beside her grave with the inscription “Yi bu wang hua,” which means “The righteous one does not forget China.”

Since the Atlanta shootings, Asian women have been assaulted and even killed. Asian people have been accused of causing COVID-19, stealing intellectual property and more. What Eaton described in her fiction and memoir continues to happen today.

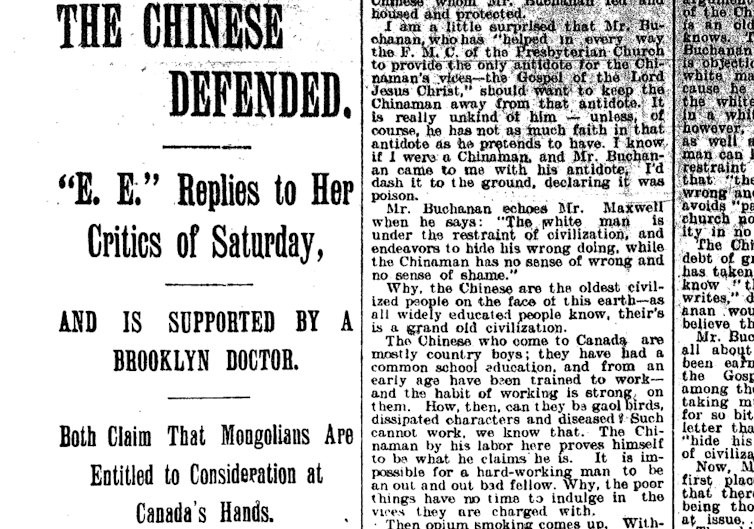

Eaton also documented anti-Chinese violence and championed the rights of Chinese immigrants in stories published in the Montréal Star and the Montréal Witness throughout the 1890s.

At the time, white men were convinced that Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs away and that Chinese men — many of whom lived alone behind their shops (because of the Head Tax — had an unfair advantage over white men with families.

In the Montréal Star, Eaton published A Plea for the Chinaman, in which she called out politicians for mistreating Chinese men in Canada:

“Every just person must feel his or her sense of justice outraged by the attacks which are being made by public men upon the Chinese who come to this country.… It makes one’s cheeks burn to read about men of high office standing up and abusing a lot of poor foreigners behind their backs and calling them all the bad names their tongues can utter.”

Anti-Chinese violence was so common in 1890s Montréal that Chinese men carried police whistles in their pockets. In an 1895 article, titled Beaten to Death, Eaton noted that even when they blew their whistles, no one would come to Chinese men’s aid. Bystanders often refused to identify their assailants and police told the men who had been assaulted that they should be arrested for bothering them.

The recent reports of a security guard’s refusal to act when a Filipino woman was brutally beaten uncannily recall the anti-Asian violence Eaton documented 125 years ago.

My research leads me to suspect that Eaton published other unsigned articles documenting anti-Chinese racism in Montreal newspapers at this time. She may have written a Gazette article reporting on youth who would gather nightly in Montreal’s Chinatown to throw stones at passing Chinese men and through the plate glass windows of their businesses, or those describing Chinese men being punched, kicked or beaten to death.

Looking at literature and journalism of the past such as Eaton’s can help illuminate the challenges of today. Her observations about people’s motivations — ignorance, jealousy, suspicion, competition — invite us to reflect on the motivations of today’s perpetrators of anti-Asian violence and conclude that not much has changed.

The anti-Asian racism recorded in Eaton’s work and journalism across Montreal persists today. Recent reports of racist violence, hate crimes, verbal harassment, opaque policing and passive bystanders could have been written more than a century ago.

We have a long way to go and a lot of work to do to make up for over a century of treating Asian people like they do not belong.![]()

Mary Chapman, Professor of English and Academic Director of the Public Humanities Hub, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.