Caitlyn Forster, University of Sydney

People may think of comics and science as worlds apart, but they have been cross-pollinating each other in more than ways than one.

Many classic comic book characters are inspired by biology such as Spider-Man, Ant-Man and Poison Ivy. And they can act as educational tools to gain some fun facts about the natural world.

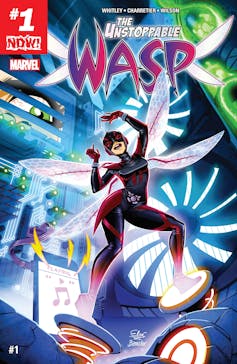

Some superheroes have scientific careers alongside their alter egos. For example, Marvel’s The Unstoppable Wasp is a teenage scientist. And DC Comics’ super-villain Poison Ivy is a botanist who saved honey bees from colony collapse.

Superheroes have also crept into the world of taxonomy, with animals being named after famous comic book characters. These include a robber fly named after the Marvel character Deadpool (whose mask looks like the markings on the fly’s back) and a fish after Marvel hero Black Panther.

Read more:

From superheroes to the clitoris: 5 scientists tell the stories behind these species names

I am a PhD student researching bee behaviour and I have spent most of my university life working at a comic book store. Here’s how superheroes could be used to make biology, and other types of science, more intriguing to school students.

1. They’re engaging

Reading has a range of benefits, from improved vocabulary, comprehension and mathematics skills, to increased empathy and creativity.

While it’s hard to directly prove the advantages of comics over other forms of reading, they can be engaging, easy to understand learning tools.

Comics have similar benefits to classic textbooks in terms of understanding course content. But they can be more captivating.

A study of 114 business students showed they preferred graphic novels over classic textbooks for learning course content.

In another study in the United States, college biology students were given either a textbook or a graphic novel — Optical Allusions by scientist Jay Hosler, that follows a character discovering the science of vision — as supplementary reading for their biology course.

Both groups of students showed similar increases in course knowledge, but students who were given the graphic novel showed an increased interest in the course.

Marvel

So, comics can be used to engage students, especially those who aren’t very interested in science.

Educational comics such as the Science Comics series, Jay Hosler’s The Way of the Hive and Abby Howard’s Earth Before Us series frequently have a narrative structure with a story consisting of a beginning, middle and resolution.

Students often find information inside storytelling easier to comprehend than when it’s provided matter-of-factly, such as in textbooks. As readers follow a story, they can use key information they have learnt along the way to understand and interpret the resolution.

2. They teach important concepts

In science-related comic books, as the story unfolds, scientific concepts are often sprinkled in along the way. For example, Science Comics: Bats, follows a bat going through a rehabilitation clinic while suffering from a broken wing. The reader learns about different bat species and their ecology on this journey.

Comics also have the advantage of permanance, meaning students can read, revisit and understand panels at their own pace.

Many science comics, including Optical Allusions, are written by scientists, allowing for reliable facts.

Using storytelling can also humanise scientists by creating relatable characters throughout comics. Some graphic novels showcase scientific careers and can be a great tool for removing stereotypes of the lab coat wearing scientist. For example, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wick’s graphic novels Primates and Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier showcase female scientists in labs, the field and even space.

The Marvel series’ Unstoppable Wasp also includes interviews with female scientists at the end of each issue.

3. They can give a visual insight into strange worlds

Imagery combined with an easy to follow narrative structure can also give a look into worlds that may otherwise be hard to visualise. For example, Science Comics: Plagues, and the Manga series, Cells at Work!, are told from the point of view of microbes and cells in the body.

Imagery can also show life cycles of animals that are potentially dangerous, or difficult to encounter, such as a honeybee colony, which was visualised through Clan Apis.

The author would like to acknowledge neuroscientist and cartoonist Matteo Farinella, whose advice helped shape this article.![]()

Caitlyn Forster, PhD Candidate, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.