The link below is to an article that reports on how Overdrive Libby now allows you to share ebooks.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-library-news/overdrive-libby-now-allows-you-to-share-ebooks

The link below is to an article that reports on how Overdrive Libby now allows you to share ebooks.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/digital-library-news/overdrive-libby-now-allows-you-to-share-ebooks

The link below is to an article that looks at rereading.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/rereading-books-3/

The link below is to an article reporting on the winners of the 2020 Davitt Awards for the best crime books by Australian women.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/09/28/157283/davitt-awards-2020-winners-announced/

The link below is to a list of Iranian fiction works regarded as essential in the article.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/35-essential-works-of-fiction-by-iranian-writers/

The link below is to an article reporting on how Kindle Create has now added Print on Demand capability.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/09/29/kindle-create-now-outputs-pod-book-files/

Tiffani Angus, Anglia Ruskin University

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 children’s book The Secret Garden has once again been adapted for the screen. Critics have noted that the film about a healing garden has come just at the right time, with The Telegraph calling it “a sparkling COVID antidote”.

Previous filmed versions appeared in 1919, 1949, and 1993. Since those iterations, however, the world has become more tech-enabled and the lives of children more dominated by screens than ever.

Ofcom in the UK estimates that the average three-to-four-year-old spends around three hours a day in front of a screen. This rises to four hours for ages five to seven, 4.5 hours by ages eight to 11, and 6.5 hours for teenagers. Time spent playing outdoors, as a result, is at an all-time low. It might be a wonder then, why, in 2020, a new film about playing outside is being released to an audience that seems so disconnected from it.

2020 has been, to say the least, an odd year. And, after a nationwide lockdown and restrictions currently being reimposed over large parts of the UK, The Secret Garden, a story about the healing qualities of nature – where magic, joy and, importantly, escape can be found – speaks to children (and adults) more than ever. “It sees a group of traumatised people who don’t get out much find solace in gardening and fresh air,” notes Helen O’Hara in Empire speaking about the similarities between the Edwardian cast of characters and our current reality.

The story follows Mary Lennox, a self-centred and neglected child, who is forced to move to her uncle’s estate in Yorkshire after her parents die from cholera in India. Left to her own devices and struggling to adjust, Mary finds distraction in exploring the estate’s vast grounds. It is on one of these jaunts that she discovers a hidden garden. Overgrown and mysterious, the place was locked years before by her uncle after his wife died in it.

The garden is, unsurprisingly, irresistible to Mary and, along with her spoiled cousin Colin who believes he’s disabled, and the good-natured Dickon, a kindly maid’s little brother, she finds that it is more than just a place to play. There nature has the power to heal, create relationships and bring joy; the garden also can help mend the wounds of the past, transforming hopeless grief to possibility.

The importance of nature as a source of healing has become increasingly clear during periods of lockdown as we find ourselves longing for green spaces as an escape from the news and our own four walls. Gardens (those of us who have them) and local parks and green spaces become important spaces where children can run around and adults can take a moment to reset. Like in The Secret Garden, we have discovered nature anew and it has restored us.

In children’s literature, gardens are a place for dreaming, adventures, and even for time travel. In books such as Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden, Lucy M Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe and Andre Norton’s Lavender-Green Magic, the garden takes children back in time. There they meet people from the garden’s history or other historically important individuals. They have run-ins with their ancestors or undertake actions to save other (usually young) characters from the past who were treated badly or in danger.

The garden is a place to “fix” mistakes and learn about the great mystery and circle of life. Gardens, also, represent time itself: they never stop growing and changing. Every seed planted carries within it the hopes we have for the future.

While The Secret Garden is not a time-travel device as such, it does act as a conduit between the past and present. In it the family’s history is exposed and reckoned with, changing the present and setting them on a course to a new, more hopeful future together.

This connection between gardens and time (and time travel) might appeal to 2020 viewers who are looking for a way to connect the past with an uncertain future. In this story that many adults hold dear, they can rediscover their childhood and escape for a moment in nostalgia for a simpler time.

Once we enter the garden, however, who we are affects how we relate to it. Children have a completely different relationship to gardens than adults: adults see the backbreaking work that goes into them, while children benefit from all that hard work and only see a place to run and play. For the children in The Secret Garden, the garden is a place of discovery, fun, and recovery, in that order. And that is possibly the main key to the story’s longevity: it feeds into a faith in nature as healing, something difficult to ignore amid the friction over climate change and the destruction of some ecosystems.

The past seven months of lockdowns have fostered a hunger for personal green spaces. With the newest film version of The Secret Garden, our love affair with gardens is again brought to the big — and small — screen, where those of us who have been stuck inside can unlock the garden gate and, with a childlike innocence we yearn for, enter a magical green wonderland to take advantage of the healing properties and timeless qualities of a garden that has been waiting for us.![]()

Tiffani Angus, Senior lecturer in Creative Writing and Publishing, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alison Baker, University of East London

Recent research from the Literacy Trust has indicated that children’s interest in and enjoyment of reading increased during lockdown. However, some children who were less confident as readers did not report that their reading was as easily supported by parents when schools and libraries were closed. As some parts of the UK go into lockdown, what books can parents and carers share with children that both adults and children can both enjoy?

In this wonderful picture book for kids aged three to six, an officious cat explains to a frog why it must sit on a log, even though it is bumpy and there is a danger of splinters in the bottom. All animals must sit on objects that rhyme, such as pumas on satsumas and gorillas on chinchillas. The inventive rhymes, combined with Jim Field’s colourful illustrations, will provide many laughs and make repeated sharing enjoyable.

Illustrations by Jim Field.

Rocket loves looking up at the stars and wants to be an astronaut when she grows up, like Mae Jamieson, the first Black woman to travel into space. Her brother Jamal, who is more interested in looking down at his phone, has promised to take her to the park to see a meteor shower, but first, they have to go to the supermarket, where Rocket tries to get the other shoppers excited with amazing space facts. Can she interest her neighbours? And will anyone else come to the park? Rocket’s enthusiasm is infectious, and the tender portrayal of the siblings’ relationship will delight adults and children six and up.

Illustrations by Dapo Adeola.

Harriet has had to move in with her gran because her dad’s lorry driving job takes him away from home. While looking for her hearing aid under her bed, Harriet finds an alien and discovers that when she wears her aid she can understand its language. Harriet learns that her gran is a member of an intergalactic security agency and Earth is under attack. Can Harriet, her new friend Robin, her gran and a sock munching alien save the planet? This funny and exciting book, from inclusive publishers Knights Of, has short chapters and lively illustrations, making it a perfect shared book for readers not quite ready to read a novel for themselves (ages six to 11).

Illustrations Jessica Flores.

Ten-year-old Morrigan Crow was born on the unluckiest day, Eventide, and as such is blamed for all misfortunes that befall her town. Worst of all, Morrigan is cursed to die midnight on her eleventh birthday. However, just before the curse can come true she is whisked away by traveller, adventurer and hotel proprietor Jupiter North to the hidden Free State city of Nevermoor, home of the Wundrus Society. Can Morrigan pass the trials to join the mysterious society? Can she outwit the Free State immigration officers? And is Morrigan’s life still in danger?

This book is enormous fun. Jessica Townsend has created a fantastic cast of characters, and it would be a wonderful book to read with or to children aged eight and above. The audiobook, read by Gemma Whelan, would also be wonderful to share.

Film writer and novelist Catherine Johnson is well known for her historical novels, and this is one of her best. In 18th-century London, Ezra McAdam, a mixed-race 16-year-old surgeon’s apprentice, foils a break-in at his master’s house. This sets off an exciting chain of events that include grave robbing and murder. Along the way he is befriended by Loveday Finch, the daughter of a man whose murdered body has similar injuries to corpses that Ezra has dissected; can Ezra and Loveday survive to find out the truth behind her father’s murder? A fantastically exciting read to be shared and discussed with readers aged ten and above.![]()

Alison Baker, Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood Studies, University of East London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

John Goodby, Sheffield Hallam University

It’s the dream of every researcher to get their hands on a hitherto-unknown manuscript by the author in whose work they specialise. As you’d imagine, most never realise that dream. But on December 9 2014 at Sotheby’s auction house in London, I was lucky enough for it to happen to me. A school exercise book that had once belonged to Dylan Thomas, filled with 16 of his poems in his handwriting, was bought by my then-employers, Swansea University, for £85,000 and given to me to edit.

A PhD student, Adrian Osbourne, was funded to help me in my labours. A greater honour, and a more daunting, more thrilling task, would have been hard for either of us to imagine.

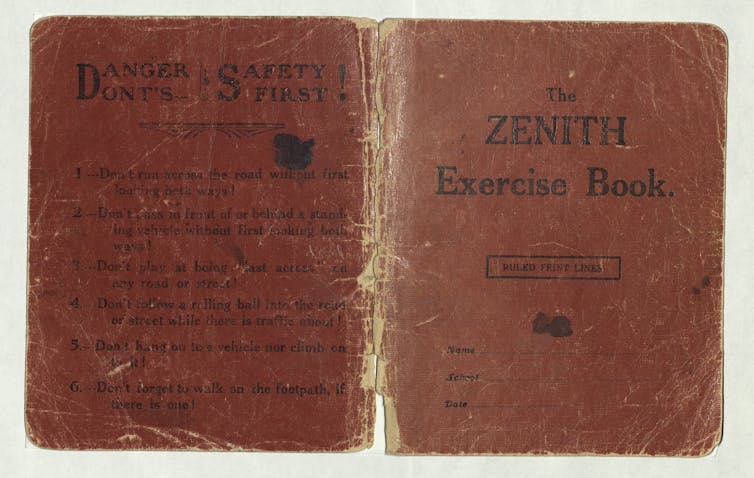

To begin at the beginning, however, some context. From April 1930, aged 15, Thomas began copying his completed poems into a series of school exercise books. In his short story, The Fight, the “D. Thomas” character notes how: “In the evening, before calling on my new friend, I sat in my bedroom by the boiler and read through my exercise-books full of poems. There were Danger Don’ts on the backs.”

In a letter of 1933, Thomas referred to an “innumerable” number of such notebooks. And, unlike most poets, he hung onto his juvenilia, carrying them around with him and raiding them for material until 1941. At that point, in the darkest days of the second world war, hard up and with a family to support, he sold the first four, which run from April 1930 to April 1934, to the library of the State University of New York at Buffalo. Scholars were given access to them and they were published in 1967 as Poet in the Making: The Notebooks of Dylan Thomas.

No more notebooks emerged during Thomas’s lifetime, nor – despite much speculation – did any appear after his death in 1953. Thus, the Sotheby’s notebook is the only one to have appeared, and it covers the period summer 1934 to August 1935 – making it a direct continuation of the first four.

The fifth notebook’s extraordinary nature as an object is matched by the story of its survival. Two notes contained in the Tesco’s bag in which the notebook was found allowed us to establish this. The first, a brief description by Thomas himself, shows that the last time he was in possession of it was early 1938.

After marrying in summer 1937, he and Caitlin Macnamara lived with Caitlin’s mother at her home in Hampshire until early 1938. The second note – by Mrs Macnamara’s maid, Louie King – revealed that after Dylan and Caitlin’s departure she was given the notebook, with other “scrap paper” they left behind, to burn in the kitchen boiler. King, however, withheld the notebook from its fiery fate – out of curiosity, sentiment, or for some other reason we know nothing about. When she died in 1984 the notebook passed to her family, who kept it, still a secret to the outside world, until 2014.

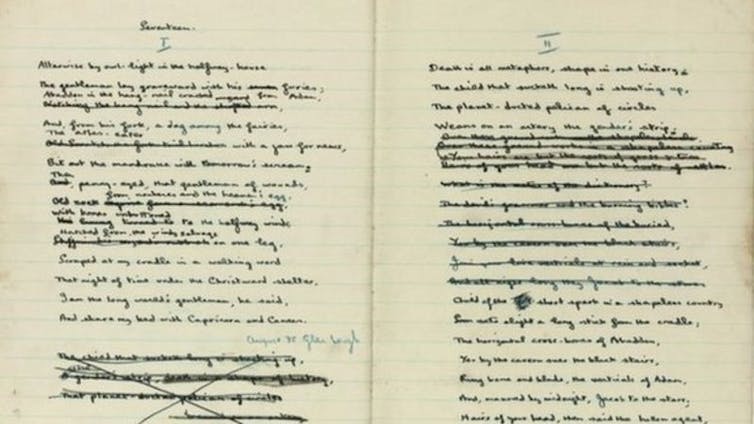

We now had three tasks – to transcribe the notebook poems, deciphering, if possible, Thomas’s many corrections and deletions. We then set out to compare them with the published versions and to work out what light – if any – they shed on Thomas’s poetic development.

It should be said that the fifth notebook poems are all published ones. Unlike its predecessors it contains no unpublished items (this may be why Thomas does not seem to have minded losing it). Where it differed was in the number of corrections it contained. The poems in the first four notebooks are almost always clean copies. In the fifth, many poems undergo radical revision, allowing us to trace Thomas’s creative processes at first hand.

Luckily, we were able to realise most of our aims. Thomas’s handwriting is clear, so most poems and corrections were easy to read. Some problems arose as the notebook progressed, and the poems grew more complex and worked-over. Usually, educated guesswork (not to mention my colleague’s keen eyesight) carried us through – although in a handful of cases we called in a technician armed with a super-photocopier. In the end only five words were unresolved.

Among the deleted passages were many of great beauty and originality, some of which Thomas reworked elsewhere. There were also three stanzas, in two of the poems, which had never been seen before.

Everywhere his incredibly rapid development as a poet was evident. Sometimes, even the tiniest item could alter our understanding of a poem; in I Dreamed My Genesis, the notebook confirmed that a comma should replace a full stop found in three print editions, making better sense of eight lines of the poem.

At the other end of the scale of significance, after poem eight, When, Like a Running Grave, we noted that Thomas had, unusually, written out the date in full: “26th October 1934” – the eve of his 20th birthday – with an emphatic line in the centre of the page. We know from the number of poems he wrote about birthdays (they include Poem on His Birthday and Poem in October) that they held great significance for Thomas. So we feel it is no coincidence that the poems that follow this point, beginning with Now and culminating in Altarwise By Owl-Light, the final poem, differ from these before it, and are the most experimental he ever wrote. Agonisingly aware of human mortality, of the end of youth, this emphatic dating marks the exact moment of Thomas’s momentous decision to adopt a more daring style.

The notebook, then, represents a kind of hinge in his early career, and this is something we could only have learned from the notebook itself, since the stylistic shift is completely obscured by the non-chronological order in which When, Like a Running Grave and Now were published. It grants us the privilege of witnessing, for the first time, the young Dylan Thomas at the height of his powers, seizing and reshaping his poetic destiny.![]()

John Goodby, Professor of Arts and Culture, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.