Wikimedia

Sally Bushell, Lancaster University

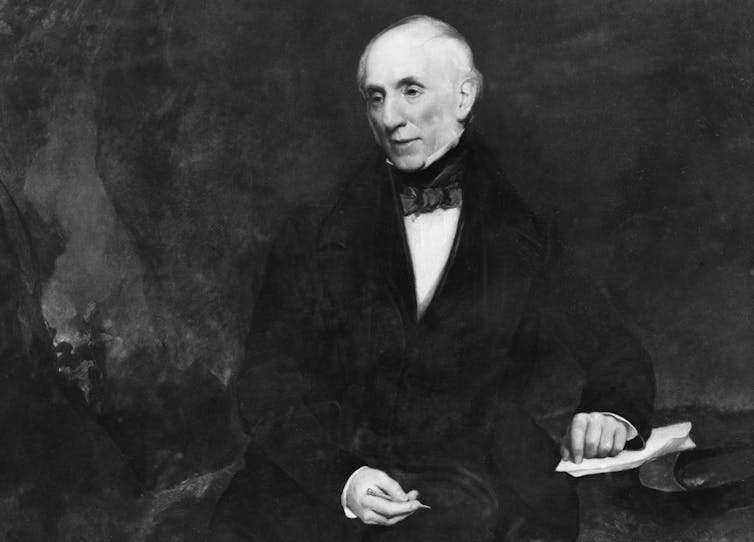

It is 250 years since the birth of the great English poet William Wordsworth. A lover of nature, his poetry abounds with images of lambs, flowers in full bloom, windswept crags and woodland scenes. His pleasure in nature, particularly that of his home the Lake District, is famous.

His contemporary Samuel Taylor Coleridge once describes his genius as “not a spirit that descended to him through the air; it sprang out of the ground like a flower.” Wordsworth did find much inspiration in the natural landscape that he would revel in on his long walks. In these house-bound times and on this anniversary, we can all find inspiration in the great poet and his love of walking as we take our daily exercise.

In a comic article from 1839 entitled Recollections of the Lakes and the Lake Poets: “Mr Wordsworth”, the writer Thomas De Quincey criticised Wordsworth’s unshapely legs while also noting that:

[He calculated], upon good data, that with these identical legs Wordsworth must have traversed a distance of 175,000 to 180,000 English miles

Wikimedia

In his summer vacation from Cambridge University in 1790, he walked right across revolutionary France, over the Alps and back through Germany (arriving late for the start of term). Wordsworth was still able to ascend Helvellyn, one of the highest peaks in the Lake District, aged 70 – a feat celebrated in Benjamin Robert Haydon’s portrait of him in 1842.

The walking Wordsworths

Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy were not only interested in large-scale walking tours but walked almost every day, at all times of the day. Dorothy’s famous Grasmere Journal, documents their walks and is itself a wonderful example of nature writing. In it she logs the minute details they would see on their walks, like daffodils near the Lake District’s Gowbarrow Park:

I never saw daffodils so beautiful. They grew about the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the lake.

Walking was not just for pleasure, though. We know that Wordsworth frequently walked to write. Dorothy’s Journal describes how:

Though the length of his walk maybe sometimes a quarter or half a mile, he is as fast bound within the chosen limits as if by prison walls. He generally composes his verses out of doors, and while he is so engaged he seldom knows how the time slips away, or hardly whether it is rain or fair.

In a poem entitled When first I Journey’d Hither to his brother John, who was away at sea, Wordsworth writes of the joy of finding a path carved into the earth by him:

With a sense

Of lively joy did I behold this path

Beneath the fir-trees, for at once I knew

That by my Brother’s steps it had been trac’d.

My thoughts were pleas’d within me to perceive

That hither he had brought a finer eye,

A heart more wakeful: that more loth to part

From place so lovely he had worn the track,

Out of his own deep paths!

The poem ends by imagining John, walking up and down on the deck of his ship at sea in tune with William as he also walks up and down to write the poem on the path that John has made for him. He imagines an empathetic connection between the two constrained spaces:

Alone I tread this path, for aught I know

Timing my steps to thine

To the rhythm

Everett Historical/Shutterstock

Wordsworth is known for composing in the rhythm with the pace of his walking. In his epic autobiography, The Prelude, Wordsworth describes himself doing this and sending his terrier (Pepper) ahead to warn him of others:

And when at evening on the public way

I sauntered, like a river murmuring

And talking to itself when all things else

Are still, the creature trotted on before;

Such was his custom; but whene’er he met

A passenger approaching, he would turn

To give me timely notice, and straightway,

Grateful for that admonishment, I hushed

My voice, composed my gait, and, with the air

And mien of one whose thoughts are free, advanced

To give and take a greeting that might save

My name from piteous rumours, such as wait

On men suspected to be crazed in brain

This is also a wonderful example of why walking alone can be freeing. It allows us to be alone with our thoughts and to act freely (till someone happens by that is).

So, as you undertake your permitted daily walk, remember that constraint can also be creative, the familiar walk enjoyable in its very familiarity. Enjoy the calm of nature and, like William’s brother, John, receive that calm as a “silent poet” appreciative and receptive to the simple pleasures around you.![]()

Sally Bushell, Professor of English and Creative writing, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.