Shutterstock

About 15 years ago I was in a Minneapolis conference centre, about to deliver a paper on elephants in Southern African fiction, when I encountered a curious local in an elevator. When I told her that one of my subjects was Wilbur Smith’s thriller, Elephant Song, she enthused,

Oh, I just loved that book; I contribute every year now to the Hohenwald Elephant Sanctuary.

I didn’t tell her that my paper critiqued the novel for being exploitative, and grossly sensationalist. Despite its title, the book is only tangentially interested in elephants – at least in comparison with Dalene Matthee’s famous Circles in a Forest, perhaps South Africa’s most eco-sensitive novel ever.

There’s no telling what people will get out of their reading. Even in our era of super-saturating graphics and television, photography and film, literature still has a considerable effect on public perceptions of environmental issues. Until very recently, of course, reading was the primary mode of information transfer. Many attitudes towards, say, elephants were established through literature, and persist in other media today.

This is the purview of my new book, Death and Compassion: The elephant in Southern African Literature. The book takes the region south of the Zambezi as its stamping-ground. It explores how various genres of literature reflect attitudes towards elephants. It takes literature in a broad sense, probing beyond the standard fiction and poetry into non-fiction forms such as hunting accounts and game-ranger memoirs.

Each chapter asks questions crucial to our understanding of our place in the natural world. It does so conscious that this understanding is the great problem of our times, superseding and enveloping all more localised and political squabbles. What is the relationship between science and compassion? Why do men hunt? How do we educate the young about animals, the environment and us? What sense of “community” might include wild and even dangerous animals?

Conflicting emotions

Elephants raise the conflicting emotions involved in humanity’s ongoing struggle to balance exploitation and well-being, damage and compassion to a particularly intense pitch.

Can we look to indigenous cultures for guidance, as conveyed by rock art, folktales and proverbs? The rock art is relatively opaque, while oral productions are now so refracted through translation into modern literary media that it’s hard to be sure what the originals’ attitudes towards elephants might have been. Reverence, awe, and taboo are evident enough, but it seems that animal compassion is an invention of modernity.

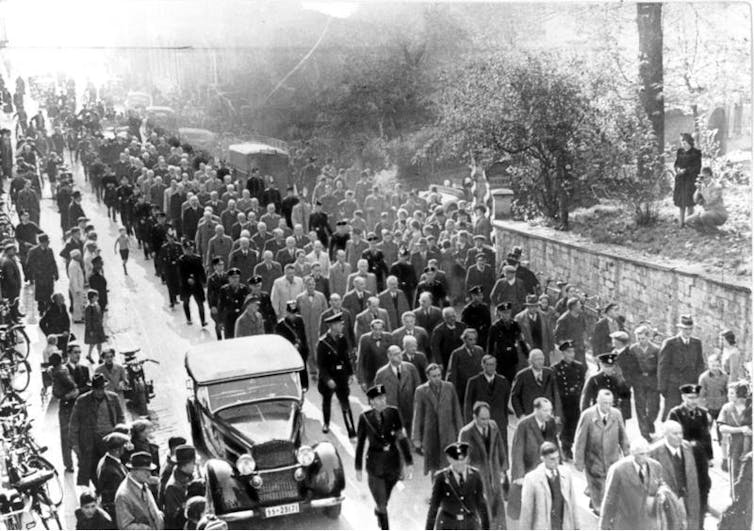

Compassion, at least as it emerges in this literature, seems to develop in response to destruction. It strengthens belatedly but proportionately to the catastrophic decimation of wildlife under invading white firepower, and the consequent sense of loss. I found the chapters on the 18th Century travel accounts (from Pieter Kolbe through François Le Vaillant to John Barrow), and the later nineteenth-century hunting accounts (from Roualeyn George Gordon-Cumming to Frederick Courteney Selous) the hardest to write.

The unremitting slaughter related by these adventurers is stomach-turning to say the least. Not that the hunters were oblivious to an ethical issue: without exception they engage at some level with already-nascent arguments for compassion.

Without exception they find literary methods to evade or suppress any emotions which impede the drive to kill. The genre is distinguished by its evasive manoeuvres designed to avoid thinking about it at all.

The adult fictions, from H. Rider Haggard to Wilbur Smith, are little better, being largely gratuitously gory adventure-tales which come to centre repetitively on a duel-like situation: single hunter versus great old tusker. It seldom ends well for the elephant.

Still, a shift becomes discernible in mid twentieth-century novels. “Conservation” is gaining traction, so the novel, just as it had migrated out of the hunting account, now drifts into some commonalities with the modern game-ranger memoir. The ranger becomes the hero, saving the tusker from poachers.

Of course, shadowing all this is the ivory trade. It had existed for centuries, drove most of the early slaughter and drives the renewed slaughter today. In some estimates, an African elephant is being killed every 15 minutes.

Ironically, because of the colonial-era establishment of game reserves like Kruger, southern Africa’s elephants so flourished that that other side of slaughter – the organised “cull” – for a time became the management tool of choice. The ethics of culling preoccupy both late novels and memoirs by rangers, scientists and managers (such as Caitlin McConnell and Lawrence Anthony).

Perception of elephants

In most recent works, the relatively new perception of elephants not just as mobile repositories of ivory but as emotionally sensitive, uniquely communicative and socially complex – almost human, even a model for humans – achieves unprecedented prominence.

This is especially so in fiction for children, in which compassion and empathy seem more acceptable, as if they are merely childish motivations for action in the world. A disastrous stance.

Poachers and ivory traders are unlikely to be persuaded by literature. Nevertheless, understanding stories – those of the murderous as well as of the compassionate – is vital to generating the critical mass necessary to save natural environments and their multiple denizens, from elephants to herons, from octopi to ants – and ourselves – from the myopia of Mammon.

Compassion alone, unanchored by economic and legislative power, is unlikely to reverse the tide of environmental destruction, but without cross-species compassion, we are surely lost.

Death & Compassion: The elephant in Southern African Literature is published by Wits University Press![]()

Dan Wylie, Professor of English, Rhodes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.