STX Entertainment

Leah Henrickson, Loughborough University

American Animals, a film recounting the true story of a 2004 rare book theft, was recently released in cinemas across the UK. The film is a dramatic retelling of events based on director Bart Layton’s interviews and written correspondence with the convicted book thieves – interactions which began while the thieves were serving seven-year prison sentences following their guilty pleas.

In 2004, four friends in their early 20s – Charles Allen, Eric Borsuk, Warren Lipka, and Spencer Reinhard – attempted to execute an elaborate plan to steal more than US$12m worth of textual treasures from Lexington, Kentucky’s Transylvania University (Transy) Special Collections.

After a year in the planning, the heist involved the men disguising themselves as elderly, shooting librarian Betty Jean Gooch with a stun gun and simply shoving valuables into backpacks. When the day came, the men managed to escape with approximately US$750,000 worth of books in their backpacks, including a first edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, an illuminated medieval manuscript, and a copy of John James Audubon’s A Synopsis of Birds of North America.

Rushing from Lexington to New York, the men attempted to appraise their loot at Christie’s, but never managed to sell their ill-gotten gains. They returned home with the books and were tracked down by the FBI within a matter of months. The entire ordeal was so poorly organised that Vanity Fair deemed it “one part Oceans 11, one part Harold & Kumar”.

Light fingers

But this was by no means the only notable rare book heist in living memory. Earlier in 2018, an audit of the special collections of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh uncovered a series of thefts of rare books and book pages with a total value of around US$8m over a period of more than 20 years. It turned out that the former manager of the Carnegie Library’s rare book room, Gregory Priore, and bookseller John Schulman had been working together to sell the stolen goods through the rare book trade and auction houses.

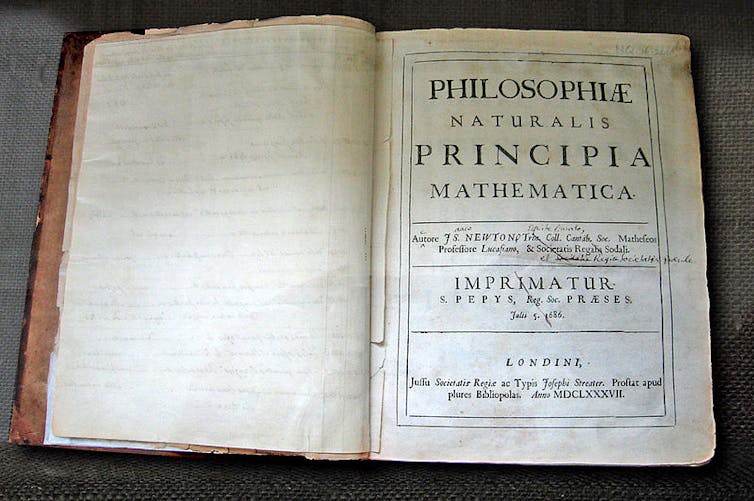

The books stolen from Carnegie included Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, a first edition of The Journal of Major George Washington, and a first edition of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Unaware of where these books came from, booksellers from across the globe bought and sold them on to their own private and institutional customers.

Andrew Dunn via Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge, CC BY-SA

These sales can be difficult to track on such a large scale and, while some works have been recovered (often at the booksellers’ own expense), hundreds of the stolen items remain missing. An up-to-date list of those items believed to have been stolen is provided by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America.

Library thefts are nothing new. Throughout the 1840s, Italian count Guglielmo Libri Carucci dalla Sommaja stole approximately 30,000 items in his job as chief inspector of French Libraries (he later made a comfortable living selling this loot in England).

More recently, in 1990, American bibiomaniac Stephen Blumberg was arrested for stealing more than 20,000 books valued at more than US$5m from more than 200 universities and museums across North America.

Wikimedia commons, CC BY-NC

He served four years in prison and became known as the “Book Bandit”.

But on a more systemic and institutional level one could go as far back as the ancient Library of Alexandria, which supposedly seized any books found on ships arriving at the port. These books were copied by professional scribes who then deposited the original works into the library and gave the copies to the books’ owners.

Book ‘em

While library thefts are commonplace, the release of American Animals and the news of the recent Carnegie Library thefts have made this crime front page news. After all, the sheer value of some of these books makes them a very attractive proposition for thieves. But it’s not always just about money – the young men in American Animals fantasise about getting their hands on culturally revered items, while Guglielmo Libri and Blumberg were bibliomaniacs with a recognised condition. And the Library of Alexandria had a larcenous ambition to become a “universal library”, gathering all of the known world’s knowledge under a single roof.

The rare book trade is lucrative, certainly. Individuals and institutions are willing to spend healthy amounts to enhance their collections. But books represent more than just profit. They are cultural artefacts that span space and time to carry the voices of those who have meaningfully contributed to the world’s knowledge. As the primary means of communication for thousands of years, books reflect and perpetuate cultural heritage and – ultimately – help us understand what it means to be human.

Whether someone is stealing books for financial gain, the thrill of the game, or the overwhelming love of these objects, library theft is always underpinned by an understanding of books as valuable cultural artefacts. The young men in the American Animals heists are animals because they tried to plunder these relics of human development.![]()

Leah Henrickson, PhD Candidate, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.