The link below is to an article that considers the new Google One service as a possible online ebook storage solution.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/will-you-store-your-ebooks-on-google-one

The link below is to an article that considers the new Google One service as a possible online ebook storage solution.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/will-you-store-your-ebooks-on-google-one

Vera Tobin, Case Western Reserve University

Recently I did something that many people would consider unthinkable, or at least perverse. Before going to see “Avengers: Infinity War,” I deliberately read a review that revealed all of the major plot points, from start to finish.

Don’t worry; I’m not going to share any of those spoilers here. Though I do think the aversion to spoilers – what The New York Times’ A.O. Scott recently lamented as “a phobic, hypersensitive taboo against public discussion of anything that happens onscreen” – is a bit overblown.

As a cognitive scientist who studies the relationship between cognition and narratives, I know that movies – like all stories – exploit our natural tendency to anticipate what’s coming next.

These cognitive tendencies help explain why plot twists can be so satisfying. But somewhat counterintuitively, they also explain why knowing about a plot twist ahead of time – the dreaded “spoiler” – doesn’t really spoil the experience at all.

When you pick up a book for the first time, you usually want to have some sense of what you’re signing up for – cozy mysteries, for instance, aren’t supposed to feature graphic violence and sex. But you’re probably also hoping that what you read won’t be entirely predictable.

To some extent, the fear of spoilers is well-grounded. You only have one opportunity to learn something for the first time. Once you’ve learned it, that knowledge affects what you notice, what you anticipate – and even the limits of your imagination.

What we know trips us up in lots of ways, a general tendency known as the “curse of knowledge.”

For example, when we know the answer to a puzzle, that knowledge makes it harder for us to estimate how difficult that puzzle will be for someone else to solve: We’ll assume it’s easier than it really is.

When we know the resolution of an event – whether it’s a basketball game or an election – we tend to overestimate how likely that outcome was.

Information we encounter early on influences our estimation of what is possible later. It doesn’t matter whether we’re reading a story or negotiating a salary: Any initial starting point for our reasoning – however arbitrary or apparently irrelevant – “anchors” our analysis. In one study, legal experts given a hypothetical criminal case argued for longer sentences when presented with larger numbers on randomly rolled dice.

Either consciously or intuitively, good writers know all of this.

An effective narrative works its magic, in part, by taking advantage of these, and other, predictable habits of thought. Red herrings, for example, are a type of anchor that set false expectations – and can make twists seem more surprising.

A major part of the pleasure of plot twists, too, comes not from the shock of surprise, but from looking back at the early bits of the narrative in light of the twist. The most satisfying surprises get their power from giving us a fresh, better way of making sense of the material that came before. This is another opportunity for stories to turn the curse of knowledge to their advantage.

Remember that once we know the answer to a puzzle, its clues can seem more transparent than they really were. When we revisit early parts of the story in light of that knowledge, well-constructed clues take on new, satisfying significance.

Consider “The Sixth Sense.” After unleashing its big plot twist – that Bruce Willis’ character has, all along, been one of the “dead people” that only the child protagonist can see – it presents a flash reprisal of scenes that make new sense in light of the surprise. We now see, for instance, that his wife (in fact, his widow) did not snatch up the check at a restaurant before he could take it out of pique. Instead it was because, as far as she knew, she was dining alone.

Even years after the film’s release, viewers take pleasure in this twist, savoring the degree to which it should be “obvious if you pay attention” to earlier parts the film.

At the same time, studies show that even when people are certain of an outcome, they reliably experience suspense, surprise and emotion. Action sequences are still heart-pounding; jokes are still funny; and poignant moments can still make us cry.

As UC San Diego researchers Jonathan Levitt and Nicholas Christenfeld have recently demonstrated, spoilers don’t spoil. In many cases, spoilers actively enhance enjoyment.

In fact, when a major turn in a narrative is truly unanticipated, it can have a catastrophic effect on enjoyment – as many outraged “Infinity War” viewers can testify.

If you know the twist beforehand, the curse of knowledge has more time to work its magic. Early elements of the story will seem to presage the ending more clearly when you know what that ending is. This can make the work as a whole feel more coherent, unified and satisfying.

Of course, anticipation is a delicious pleasure in its own right. Learning plot twists ahead of time can reduce that excitement, even if the foreknowledge doesn’t ruin your enjoyment of the story itself.

![]() Marketing experts know that what spoilers do spoil is the urgency of consumers’ desire to watch or read a story. People can even find themselves so sapped of interest and anticipation that they stay home, robbing themselves of the pleasure they would have had if they’d simply never learned of the outcome.

Marketing experts know that what spoilers do spoil is the urgency of consumers’ desire to watch or read a story. People can even find themselves so sapped of interest and anticipation that they stay home, robbing themselves of the pleasure they would have had if they’d simply never learned of the outcome.

Vera Tobin, Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science, Case Western Reserve University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at saving rare books from climate change.

For more visit:

https://psmag.com/environment/saving-our-archives-from-climate-change

The link below is to an article that asks ‘are ebooks too expensive in 2018?’

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/are-ebooks-too-expensive-in-2018

I certainly don’t agree with all of the comments in the article, though they seem typical for this particular writer.

Ian Higgins, Australian National University

In our series, Guide to the classics, experts explain key works of literature.

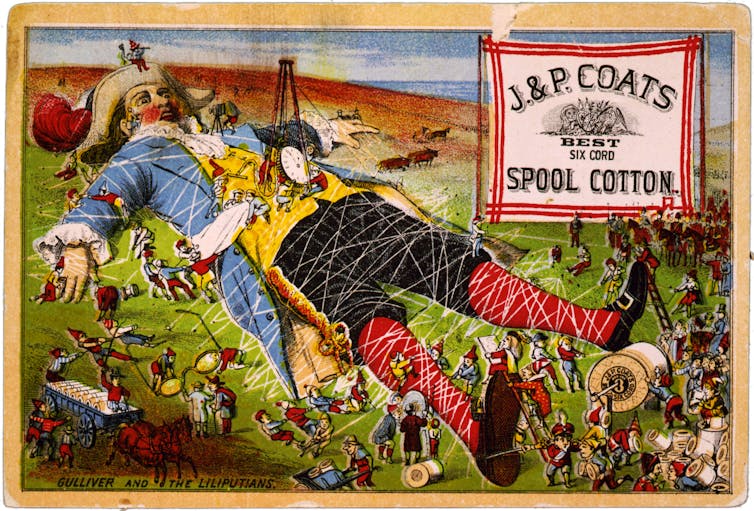

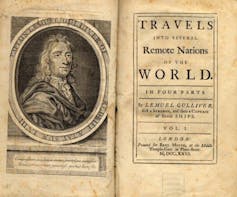

Pick up Gulliver’s Travels expecting a children’s book or a novel and you will be unpleasantly surprised. Originally published as “Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts … By Lemuel Gulliver, first a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships”, it is one of the great satires in world literature.

First published in London in 1726, the Travels was a sensational bestseller and immediately recognised as a literary classic. The author of the pseudonymous Travels was the Church-of-Ireland Dean of St. Patrick’s in Dublin, Jonathan Swift. Swift wrote that his satiric project in the Travels was built upon a “great foundation of Misanthropy” and that his intention was “to vex the world”, not entertain it.

The work’s inventive narrative, exuberant fantasy (little people, giants, a flying island, spirits of the dead, senile immortals, talking horses and odious humanoids), and hilarious humour certainly made the work entertaining. In its abridged and reader-friendly form, sanitised of sarcasm and black humour, Gulliver’s Travels has become a children’s classic. In its unabridged form, however, it still has the power to vex readers.

Read more:

Why you should read China’s vast, 18th century novel, Dream of the Red Chamber

In Part 1 of this four-part satire, Gulliver is shipwrecked among the tiny Lilliputians. He finds a society that has fallen into corruption from admirable original institutions through “the degenerate Nature of Man”. Lilliput is a satiric diminution of Gulliver’s Britain in its corrupt court, contemptible party politics, and absurd wars.

In Part II Gulliver is abandoned in Brobdingnag, a land of giants. The scale is now reversed. Gulliver is a Lilliputian among giants, displayed as a freak of nature and kept as a pet. Gulliver’s account of his country and its history to the King of Brobdingnag leads the wise giant to denounce Gulliver’s countrymen and women as “the most pernicious Race of little odious Vermin that Nature ever suffered to crawl upon the Surface of the Earth”.

In Part III Gulliver is the victim of piracy and cast away. He is taken up to the flying island of Laputa. Its monarch and court are literally aloof from the people it rules on the continent below, and absorbed in pure science and abstraction.

Technological changes originating in this volatile “Airy Region” result in the economic ruin of the people below and of traditional ways of life. The satire recommends the example of the disaffected Lord Munodi, who is “not of an enterprising Spirit”, and is “content to go on in the old Forms” and live “without Innovation”. Part III is episodic and miscellaneous in character as Swift satirises various intellectual follies and corruptions. It offers a mortifying image of human degeneration in the immortal Struldbruggs. Gulliver’s desire for long life abates after he witnesses the endless decrepitude of these people.

Part IV is a disturbing fable. After a conspiracy of his crew against him, Gulliver is abandoned on an island inhabited by rational civilised horses, the Houyhnhnms, and unruly brutal humanoids, the Yahoos. Gulliver and humankind are identified with the Yahoos. The horses debate “Whether the Yahoos should be exterminated from the Face of the Earth”. As in the story of the flood in the Bible, the Yahoos deserve their fate.

The horses, on the other hand, are the satire’s ideal of a rational society. Houyhnhnmland is a caste society practicing eugenics. Swift’s equine utopians have a flourishing oral culture but there are no books. There is education of both sexes. They have no money and little technology (they do not have the wheel). They are authoritarian (there is no dissent or difference of opinion). The Houyhnhnms are pacifist, communistic, agrarian and self-sufficient, civil, vegetarian and nudist. They are austere but do have passions. They hate the Yahoos.

Convinced that he has found the enlightened good life, free of all the human turpitude recorded in the Travels, Gulliver becomes a Houyhnhnm acolyte and proselyte. But this utopian place is emphatically not for humans. Gulliver is deported as an alien Yahoo and a security risk.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Sappho, a poet in fragments

Wearing clothes and sailing in a canoe made from the skins of the humanoid Yahoos, Gulliver arrives in Western Australia, where he is attacked by Aboriginal people and eventually, unwillingly, rescued and returned home to live, alienated, among English Yahoos. (Swift’s knowledge of the Aboriginal people derives from the voyager William Dampier, whom Gulliver claimed was his “Cousin”.)

When it was published, the Travels’ uncompromising, misanthropic satiric anatomy of the human condition seemed to border on blasphemy. The political satire was scandalous, venting what Swift called his “principle of hatred to all succeeding Measures and Ministryes” in Britain and Ireland since the collapse, in 1714, of Queen Anne’s Tory government, which he had served as propagandist.

In its politics the work is pacifist, condemns “Party and Faction” in the body politic, and denounces colonialism as plunder, lust, enslavement, and murder on a global scale. It satirises monarchical despotism yet displays little faith in parliaments. In Part III we get a short view of a representative modern parliament: “a Knot of Pedlars, Pickpockets, Highwaymen and Bullies”.

Gulliver’s Travels belongs to a tradition of satiric and utopian imaginary voyages that includes works by Lucian, Rabelais, and Thomas More. Swift hijacked the form of the popular contemporary voyage book as the vehicle for his satire, though the work combines genres, containing utopian and dystopian fiction, satire, history, science fiction, dialogues of the dead, fable, as well as parody of the travel book and the Robinson Crusoe-style novel.

It’s not a book to be judged by its cover. The frontispiece, title page and table of contents of the original edition gave no hint that this was not a genuine travel account. Swift and his friends reported stories of gullible readers who took this hoax travel book for the real thing.

It is also not reader friendly. The revised 1735 edition of the Travels opens with a disturbing letter from Gulliver in which the reader is arraigned by an irate and misanthropic author convinced that the “human Species” is too depraved to be saved, as evidenced by the fact that his book has had no reforming effect on the world. The book ends with Gulliver, a proud, ranting recluse, preferring his horses to humans, and warning any English Yahoos with the vice of pride not to “presume to appear in my Sight”.

Readers might dismiss the unbalanced Gulliver, but he is only saying what Swift’s uncompromising satire insists is the truth about humankind.

![]() In many ways Jonathan Swift is remote from us, but his satire still matters, and Gulliver’s Travels continues to vex and entertain today.

In many ways Jonathan Swift is remote from us, but his satire still matters, and Gulliver’s Travels continues to vex and entertain today.

Ian Higgins, Reader in English, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Thomas Kaiserfeld, Lund University

The Swedish Academy has announced it will not select a Nobel laureate in literature for 2018. Instead, two laureates will be appointed 2019, one for 2018 and one for 2019. The decision is not unique. The prize has been withheld on no fewer than seven occasions in the past and it has also been postponed for a year five times previously – the last time being in 1949.

The reason for postponing the prize this time, however, is exceptional since it is not related to the academy’s inability to unify behind one single candidate, but is instead the consequence of a more general crisis in the academy in which a number of members resigned their posts over a scandal relating to allegations of sexual harassment made against the husband of one of the members.

According to the academy, the reason for the decision is more specifically the number of members who have withdrawn from participating in its work. Eight members of 18 are no longer academy participants, which will impede its work, and make it hard to evaluate the different authors nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature in particular. Another motive for the decision to postpone, the academy’s announcement said, was the necessity to restore the academy’s reputation after a few months filled with accusations and scandal.

Glancing through the list of Nobel Prizes in literature over the years, from the very first that was awarded in 1901 to French poet and essayist Sully Prudhomme, to the most recent winner, British author Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017, reveals a mix of world-famous authors and names hardly even remembered today by specialists.

French author François Mauriac, Nobel laureate in 1952, is probably not commonly read anymore, if he ever was. There are also a number of laureates who were rewarded more for their general contributions to human thinking and culture than their skills in literature – persons such as Bertrand Russell (1950), Winston Churchill (1953) and Jean-Paul Sartre, who was selected in 1964 only to decline the prize.

In 1914, when deliberations were upset by the beginning of World War I, the Nobel Prize was withheld. The following year, in 1915, the prize was postponed and was given to the French author Romain Rolland in 1916. The same thing happened in 1918 when the prize was withheld and then the selection of the 1919 laureate, the Swiss author Carl Spitteler, was delayed by a year. To award an author from neutral Switzerland seems to have been safe bet in a time of excited feelings following the end of the war.

In 1935, no prize was awarded and in 1936 it was postponed, because “the Nobel Committee for Literature decided that none of the year’s nominations met the criteria as outlined in the will of Alfred Nobel”. The 1936 award went to Eugene O’Neill. The same thing happened again during World War II when no prizes were awarded between 1940 and 1943. In 1944, the prize was again postponed to be given to the Danish author Johannes Jensen in 1945 after the war had ended (the 1945 prize went to Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral). The prize of 1949 was postponed by 12 months because the committee couldn’t find a suitable laureate. The 1949 prize was awarded to William Faulkner in 1950. Since then, Nobel laureates in literature have been selected regularly. But not any more.

The decision to postpone the Nobel Prize in literature 2018 for one year has surprised many commentators. The loss of prestige for the academy is considerable and the decision to postpone the Nobel Prize can only be interpreted as the recognition by the remaining ten members of the academy the need for reform.

Read more:

Nobel Prize crisis: flurry of withdrawals rocking Swedish Academy’s showpiece literature award

The shortlist of authors nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature also changes only slowly from year to year. So the four members of the Nobel Committee for Literature (there should normally be five, but one is among those eight who have left the academy) should already know all about them. The work already done to evaluate earlier shortlisted authors, then, could surely have been used to select a laureate for 2018. So, the decision to postpone the prize should be taken as a sign of how serious the remaining ten members of the Swedish Academy view the turmoil that is disrupting their organisation.

![]() The Nobel Foundation – which is ultimately responsible for administering the intentions of the will of Alfred Nobel – has said it supports the decision made by the Swedish Academy. The foundation has also made it clear that the postponing of the literature prize does not affect other Nobel Prizes in physics, chemistry, medicine and peace.

The Nobel Foundation – which is ultimately responsible for administering the intentions of the will of Alfred Nobel – has said it supports the decision made by the Swedish Academy. The foundation has also made it clear that the postponing of the literature prize does not affect other Nobel Prizes in physics, chemistry, medicine and peace.

Thomas Kaiserfeld, Professor at Division of History of Ideas and Sciences, Lund University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at what a ‘hard-boiled’ novel actually is.

For more visit:

http://crimereads.com/what-is-a-hard-boiled-novel/

The link below is to an article that looks at what it means to be ‘well read.’

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/may/12/book-clinic-what-constitutes-well-read

You must be logged in to post a comment.