The link below is to an article on Shakespearean insults and includes an infographic so you can come up with your own.

For more visit:

https://www.invaluable.com/blog/shakespearean-insults/

The link below is to an article on Shakespearean insults and includes an infographic so you can come up with your own.

For more visit:

https://www.invaluable.com/blog/shakespearean-insults/

The link below is to an article covering the winners for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for books.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/2018/04/16/2018-pulitzer-prize-winning-books/

The BBC’s latest drama series, an adaptation of China Miéville’s 2009 novel The City and The City, is a police procedural – but with a difference. The series is set in a fictitious divided city – Besźel and Ul Qoma – where the residents of each side are allowed no contact with each other. The main character, Inspector Tyador Borlu (played by David Morrissey), is a resident of Besźel – a slightly grubby, down-at-heel kind of place. During an investigation, he has to travel to the other city, Ul Qoma, and in order to heighten the difference for both the character and the audience, the Ul Qoman language of Illitan had to be completely different.

This is where I came in. As a linguist, I was called in to design a distinctive language for the series. This is not as uncommon as it sounds – there have been a number of languages created over the years, for various reasons. The American linguist Arika Okrent lists 500 in her book In the Land of Invented Languages which goes well beyond the usual suspects of Esperanto, Elvish and Klingon.

Constructed languages, or conlangs, have been gaining popularity in recent years, with their own society, the Language Creation Society, and annual conference. The seventh annual conference was held in July 2017 in Calgary – and even a brief look at the schedule of talks will tell you that these people take language construction extremely seriously (“(Ab)using Construction Grammar (CxG) as a Conlanging Tool”) but also have a sense of humour (“Someone from That Planet Might Be in the Audience”).

Of course, J.R.R. Tolkien created languages for Lord of the Rings – and there is a huge amount of detail on those languages for anyone with enough interest to pursue it. But in what is now widely regarded as the golden age of television, with multiple providers needing content for their channels, there is a broader scope for invention and fantasy – which is where language invention comes into its own.

The most famous example of a language created specifically for film and television is Klingon, originally created by Marc Okrand for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Klingon has since taken on a life of its own, with a Klingon Language Institute and translations of Hamlet and Much Ado About Nothing. More recently, HBO’s television adaptation of the Game of Thrones books required the creation of the Dothraki and Valyrian languages, for which David J. Peterson was responsible.

While Tolkien left some fairly detailed instructions regarding the structure and vocabulary of Elvish, most authors do not go into such detail. George R.R. Martin makes reference to the languages in his Game of Thrones novels, but Peterson created them. Likewise, while Miéville gives a number of hints about the sound and structure of Illitan, there was no grammar or dictionary to refer to. Having free rein to create a language – not purely as an academic construct, but one which will be used – is both a challenge and a joy.

The primary concern for what we might term “artistic” language creators is the ease of pronunciation for the actors. If we are being asked to produce a human language, then we have the luxury of our previous study of language and linguistics to guide us. If asked to create an alien language – as Okrand was – there might be limitless possibilities, but the actors still have to be able to physically say the lines; we are constrained by human physiology. This was not an issue in the adaptation of Story of your Life by Ted Chiang (which was filmed using the title Arrival), as the aliens communicated telepathically – although the writing system had to be created by the design team.

In his novel The City and The City, Miéville tells us that Illitan uses the Roman script, having lost its original, right-to-left script “overnight” in 1923 (we’re not told how or why). We know that Borlu finds the sound of Illitan “jarring” (although we know from Miéville’s description of the character that he speaks “good” Illitan). In Besźel, meanwhile, people speak Besz, but for the purposes of the TV adaptation this is rendered as English and the written language, despite its occasional Cyrillic intrusions and diacritics (accents, for example), is still understandable to an English-speaking audience.

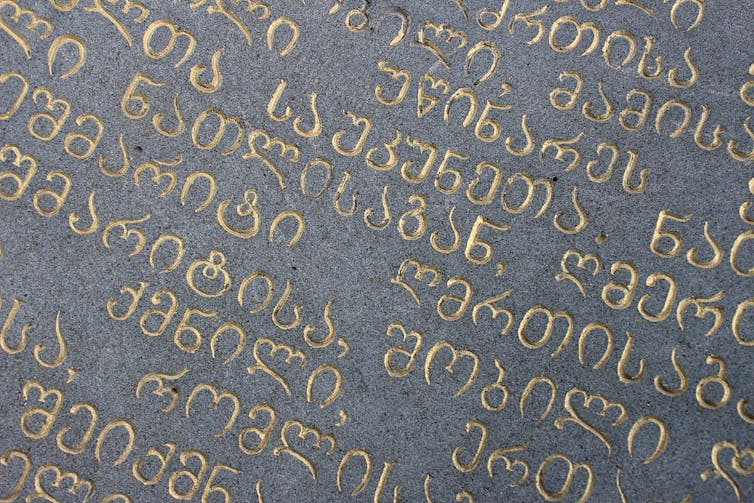

In order for the audience to share in Borlu’s sense of alienation in Ul Qoma, the decision was taken to use an entirely different alphabet for Illitian for the television series – and we eventually settled on the Georgian alphabet as it bears no resemblance to English.

The grammar of Illitan is made up of a mixture of Slavonic languages (such as Slovene, with its extra verb conjugation referring to two people: “we two are”, “you two are”, “they two are” as well as “we are”, “you are”, “they are”) and a system of infixes (like a prefix, but it fits into the word rather than in front of it) to denote tense and aspect. The word order remained roughly the same as English in order to help the actors know where to put the emphasis in their lines.

One final problem when creating a language from a novel is one familiar to any adaptation – the expectations of the audience. With any adaptation, the audience is divided into those who know the original novel and those who do not. Those who do will always have their own ideas about how the characters look and sound – and this extends to fictional language.

![]() My version of Illitan will not necessarily match up with that of a fan of The City and The City, but I hope it will add something for people who are new to Miéville’s work.

My version of Illitan will not necessarily match up with that of a fan of The City and The City, but I hope it will add something for people who are new to Miéville’s work.

Alison Long, Programme Director, Modern Languages, Keele University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Amy Rushton, Nottingham Trent University

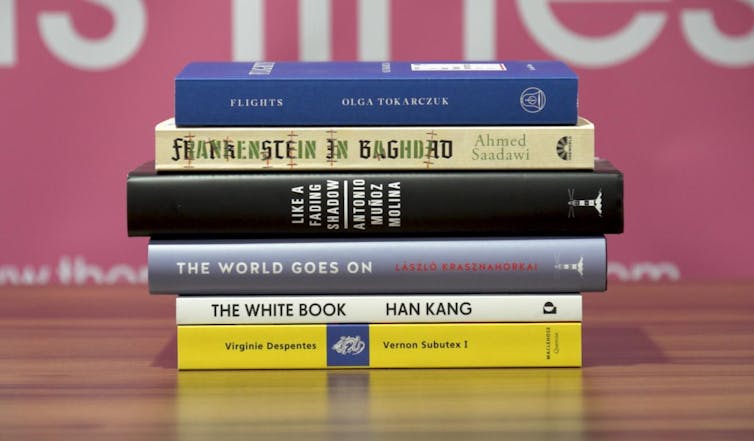

Six books, six languages, two former winners and a bonanza for independent publishers: the Man Booker International Prize – the UK’s most prestigious prize for translated fiction – has announced its 2018 shortlist. Whittled down from a longlist of 13 titles spanning the globe, the six titles to make the cut are translated from Arabic, French, Hungarian, Korean, Spanish and Polish.

This year’s nominations have been selected by a panel of five judges, chaired by novelist Lisa Appignanesi with fellow writers Hari Kunzru and Helen Oyeyemi alongside poet and translator Michael Hofmann and journalist Tim Martin. The shortlist includes Han Kang and Deborah Smith – who won the prize in 2016 for The Vegetarian – and László Krasznahorkai – who won the prize in its former iteration in 2015 – when it was awarded for an achievement in fiction evident in a body of work.

The winner of the 2018 prize will be announced on May 22 at a formal dinner at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London – and the £50,000 prize will be divided equally between the author and the translator of the winning book.

The Booker Prize Foundation has rejigged the flagship award in recent years. An awful lot of handwringing has been devoted to the decision to include US authors as contenders for the “main” award, The Man Booker Prize. But very little attention has been paid to the decision to overhaul the group’s international prize. Originally introduced in 2005, the Man Booker International Prize was intended as a global-facing sister award – with a twist. The original version of the International prize was a biennial award honouring an entire body of work by a living writer of any nationality and in any language (as long as their work was available in English).

The original format was a noble pursuit, but the Man Booker International was inevitably overshadowed on the global literary stage by the Nobel Prize for Literature. As of 2016, the Man Booker International Prize now awards a single book – but one that has been originally written in a language other than English, then subsequently translated and published in the UK.

The International Prize’s unique selling point is the emphasis on collaboration between author and translator, even down to sharing the prize money. The focus on collaboration is what makes the International Prize, for me, a truly exciting event in the literary awards calendar.

Arguably, the change has been for the better but the comparative lack of attention on the international award is still indicative of mainstream publishing’s general disinterest in translated fiction – bar the occasional bestselling “Scandi Noir” and international phenomenon such as Italy’s Elena Ferrante, of course, the latter shortlisted for the prize in 2016, along with translator Ann Goldstein.

Although we shouldn’t be tempted to see the commercial popularity of Jo Nesbø and the relative success of Ferrante as a sea change in translated fiction’s fortunes in UK publishing, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic. Adam Freudenheim of Pushkin Press suggests that “there’s definitely greater and wider awareness of fiction in translation as a result of such successes”, pointing to the new format of the Man Booker International Prize as “doing a great deal to raise the profile of such books”.

Crucially, the prize is raising the profile of those small presses and independent publishers who are at the vanguard of translated literature. As well as the aforementioned Pushkin Press, notable small publishers specialising in translated literature include Tilted Axis Press and And Other Stories. This year’s shortlist is dominated by titles from independent presses, including two books from Tuskar Rock Press, and one each from MacLehose Press, Portobello Books, Oneworld and Fitzcarraldo Editions.

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

The role of independent publishers in supporting translated literature is not lost on the judges for the International Prize: announcing the longlist earlier this year, Appignanesi declared: “I think we have to raise our hats to independent publishers. It does cost money to translate, it’s harder to publish, harder to sell.”

The International Prize has even had a direct impact on the range of translated literature available in the UK: Kang and Smith’s inaugural win in 2016 for The Vegetarian meant that Smith had extra funds for her non-profit small press, Tilted Axis – which is “on a mission to shake up contemporary international literature”.

Translated fiction may be a small part of the British reading diet but it is one that is steadily growing. In 2015, The Bookseller reported that translated fiction only accounted for 1.5% overall and 3.5% of published literary fiction. Yet translated fiction provided 5% of total fiction sales in 2015.

![]() Only time will tell if the appetite for translated fiction in the UK can continue. In the meantime, let’s toast the shortlisted authors and translators. If you’ve yet to enjoy translated fiction, this year’s shortlist is a good place to expand your global reading life.

Only time will tell if the appetite for translated fiction in the UK can continue. In the meantime, let’s toast the shortlisted authors and translators. If you’ve yet to enjoy translated fiction, this year’s shortlist is a good place to expand your global reading life.

Amy Rushton, Lecturer in English Literature, Nottingham Trent University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Ben Etherington, Western Sydney University

Alexis Wright’s book Tracker: Stories of Tracker Tilmouth has won the 2018 Stella Prize. Tracker is, in Wright’s words, an attempt to tell an “impossible story”, using the voices of many people to reflect on the life of Tilmouth, a central and visionary figure in Aboriginal politics.

At one telling point in the book, Gulf of Carpentaria activist and political leader Murandoo Yanner relates an encounter between Tracker and Jenny Macklin, then Minister for Indigenous Affairs in the Rudd government. Tracker was helping Yanner to lobby Macklin over the Wild Rivers legislation in Queensland.

Notoriously, Macklin had persisted with the Howard government’s “Northern Territory Intervention”, and was regarded with suspicion by most Aboriginal leaders. Nevertheless, she was the federal minister and had to be dealt with.

As they approached, Tracker called out, “How ya going, Genocide Jenny?”

Yanner recalls the atmosphere that followed: “You could have heard a pin drop and pistols drawn at twenty paces, and the whole thing went sour pretty quickly”.

It tells you a lot about the man. He had regular access to the corridors of power yet still called a spade a spade. He was capable of dealing with politicians of any background and station yet did not forfeit his never-back-down attitude.

He was able to gain the upper hand from the first with an irreverent comment. And, above all, he was a funny bugger. (Another memorable thumbnail character sketch, this one related by Tracker himself, is of current senator Pat Dodson as a “mobile wailing wall”: a place where white people go to confess and forgo their sins.)

It also tells you a lot about Wright’s epic tribute to Tracker. We do not read Wright quoting Yanner, but hear the whole yarn directly from the source. Born in 1954, Tracker was one of the stolen generation. His life spanned the latter years of the White Australia policy, when Aboriginal people were still legally part of the nation’s fauna, to the tumultuous period in Aboriginal politics following the Intervention, until his death in 2015.

Read more:

Provocative, political, speculative: your guide to the 2018 Stella shortlist

This is not a book about Tracker’s life authored by Wright, but consists of stories and recollections told to Wright by the man himself as well as 50 others, from family and school mates, to Aboriginal and non-Indigenous leaders in our time. Wright brilliantly intersperses and weaves these together into an epic of stories and storytelling.

As the tributes to Tracker have flowed in the months since its publication, and many will surely follow as it garners further prizes and draws in ever more readers, so have proliferated the attempts to describe both the work’s genre and the mode of authorship it enacts.

In their award statement, the Stella judges call it a “biography”, but also “new way of writing memoir”. These descriptors capture aspects of the book – a birth to death tale does emerge from Wright’s layering of stories, and these are, of course, conjured from memory – but they also obscure.

Wright didn’t “write” the work but elicited the stories that comprise it through conversation. Towards the end of the book there is an unbroken sequence of nearly 100 pages of Tracker and Wright conversing, the contents of which are largely a mixture of philosophy and political economy. In these pages, Tracker’s voice is mostly serious, even earnest, as he expounds on the need to create a sustainable economic basis on which Aboriginal people can palpably enjoy their hard-won land rights and native title.

While it is no doubt true that readers accustomed to biographies in the European tradition will be struck by the novelty of reading a tribute to a storyman made up of many stories, Tracker’s strengths as a work are are not dependent on this putative departure from the biographical genre. It is simply remarkable to hear Tracker’s genuinely funny jokes and stories told repeatedly, often word for word and channelling Tracker’s unmistakable style, by such a range of different speakers. Over the course of the book, the repetition of these stories consolidates them and imprints them on the memory.

![]() It is fitting that a book written in the mode and genre of Aboriginal storytelling should win a prize that encompasses both non-fiction and fiction. It is a work, epic in scope and size, that will ensure that a legend of Central Australian politics is preserved in myth.

It is fitting that a book written in the mode and genre of Aboriginal storytelling should win a prize that encompasses both non-fiction and fiction. It is a work, epic in scope and size, that will ensure that a legend of Central Australian politics is preserved in myth.

Ben Etherington, Senior Research Lectureship-literature, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Camilla Nelson, University of Notre Dame Australia

Six years ago, The Stella Prize burst onto the Australian literary scene with an air of urgency. The A$50,000 award was the progeny of the Stella Count – a campaign highlighting the under-representation of women authors in book reviews and awards lists. In the years since, the prize has challenged the gendered ways in which we think about “significance” and “seriousness” in literature.

Judging a literary award is invariably a contest of aesthetics and politics. And the Stella has never shied from difficult, taxing or surprising choices. It has awarded nonfiction in a field traditionally dominated by fiction; first time writers rather than established names; and in an increasingly commercialised and globalising literary marketplace, it has consistently championed the work of small and independent publishers.

There is, nonetheless, something distinctive about a Stella book. It often draws attention to the pressing social issues of our times – not only gender bias, but also racial prejudice and social and economic inequality – and testifies to the enduring significance of more intimate human themes: sickness and death, grief, love or family. The one quality the books share, I suspect, is that of provocation.

A Stella winner is a book that challenges its readers; it attempts to do a bit of work in the world. And this year’s Stella shortlist doesn’t disappoint.

Azar’s novel narrates the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution through the eyes of a 13-year-old girl, Bahar, who is burnt to death two days before the revolution reaches its height. Militants “boiling” with “hatred and fervour” break into her family home, pour kerosene across the tables, and set them alight, crying “God is great, God is great!”

Bahar narrates the story as a ghostly presence at the centre of her once happy family. The mass slaughter of dissidents, the execution of her brother, the rape and murder of her sister; such events are rendered as unremarkably as her sister’s transformation into a mermaid and her mother’s attainment of enlightenment in the greengage tree.

It is a convention of magic realism that the narrator remains estranged and distant, withholding any kind of explanation, even as ordinary life is invaded by elements of terror that are too strange to believe. This is an uneasy tension – holding beauty and horror together in a single sentence. The effect, in this novel, is to suggest that no conventional means exists to render such realities explicable.

To read a book by Michelle de Kretser is to fall in love with the novel all over again. There are few ironists so scathing and few stylists so astonishing that they can demolish a character’s pretensions in a few deft strokes. Her latest work maps the gaucheries of Australian literary, intellectual and academic life. Here, the appearance of virtue is more important than its actuality. BioBags and free-range eggs are no less status objects than designer dresses and the right shade of red lipstick.

The novel opens with the character of George Meshaw, the author of many “abstract but oppressive” books (one of which is ominously titled Necessary Suffering). George soon exits right, clearing the stage for a plethora of equally self-involved people, all of whom dutifully cart around his books, largely unread. Linking their stories is George’s undergraduate student Pippa Elkinson. “I love English,” Pippa gushes at one point. “In that case, I suggest you learn to write it,” replies George.

Pippa is all confidence and fakery. She travels abroad to gather experiences for her writing, which she insists, without a hint of irony, is based on reality. She leaves warm, supportive comments on the Twitter accounts of her carefully cultivated friends, while her agent runs her books through a simulated audience reaction indicator to test their market value. Pippa is all surface, though she later turns out to have surprising depths. As the narrator dryly observes, “Pippa would always need to demonstrate her solidarity with the oppressed – Indigenous people or battery hens, it scarcely mattered.”

Narcissism of all kinds is the target of this novelist’s ire. But de Kretser works her magic less through the classic tool of empathy – the recognition that other people are also human beings with feelings – than the shock of seeing our own little lives through the perspective of someone else’s.

Coleman’s debut novel uses the tools of speculative fiction to gain fresh insights into the history of Indigenous dispossession. It opens with Jacky Jerramungup, an Indigenous boy stolen at an early age to be used as cheap rural labour, fleeing across the country – evading capture at a mission run by sadistic nuns, eluding the Troopers and native police sent by a murderous colonial administrator to hunt him down.

Each chapter opens with a fragment from the archives of colonial bureaucracy, which appears convincingly real, but is Coleman’s invention. This is not the only strange or unexpected thing in her work. Half way through the book, what feels like a novelistic landscape drawn from the moral cesspit of the 19th century turns out to be the scene of some future invasion – a feverish figment of a dystopic dreamtime at the end of the present century.

This speculative terror – an invasion of spaceships bearing aliens from other planets in search of moisture – draws attention to the other, more familiar history of invasion, which is ongoing. As one character observes, “This has happened before, the English believed they had exterminated all of the Tasmanian Aborigines, the Palawa, in fact they survived the invasion, they still exist now.”

Kneen’s adventures in speculative erotica are invariably amusing and playful, but also strangely sad, if not overtly sentimental. In a series of interlinked stories spanning a century from the near present to a post-human future, Kneen explores questions of sex, science and gender at a time in which the boundaries between humanity and machinery are beginning to dissolve. In a complex feat of speculative world building, the novel leaps forward in stages to catch a glimpse of a post-apocalyptic future in which sea levels have risen, water has flooded the cities, and jellyfish inhabit our cellars and basements.

Along the way, we meet an array of odd characters: Caspar, a middle-aged academic who climbs into a virtual skin suit to inhabit the point of view of the young female student he seduced and then discarded; Cameron, a teenage sex-robot built to aid studies in hebephilia who begins to have thoughts and feelings of his own; Ronnie, a child sex offender, whose mind fuses with a school of jellyfish.

Behind all this, the central – if submerged – controlling presence in the novel is Liv, a writer working at the interface of technology and narrative. Liv is 129 years old at the book’s end, seeking to find out what it means to be a human living in a post-human world.

Riwoe writes against the grain of W. Somerset Maugham’s classic short story “The Four Dutchmen” – a tale about a “Malay girl” brought on board a Dutch tramp ship, plying its lucrative trade in the waters off Indonesia. Upsetting the balance of homosocial shipboard life, the “Malay trollop” is casually slaughtered and thrown into the sea.

The desire to rework the subjectivities of colonial characters – giving them air and life – is a marked cultural tendency of our time, a product of this century’s interest in reclaiming the voices of the oppressed and marginalised. Many of these stories, like Jean Rhys’s postcolonial classic The Wide Sargasso Sea, centre on reclaiming the voices of women. And yet, there is a kind of horror in the experience of inhabiting the point of view of characters who are so obviously destined for tragedy.

Riwoe gives the “Malay girl” a name – Mina – together with a set of hopes, dreams and aspirations, but Mina’s choices are narrow, and her trajectory through the world is marked by a terrifying lack of agency. The perfumed air, the gorgeous food, the tropical vegetation, do nothing to alleviate the suffocating sadness. The “Malay girl” is traded by her father, and ultimately discarded as “bad rubbish”. Riwoe takes advantage of the novella form to deliver an ending that is brutal, sharp and lingering.

Wright’s non-fiction study of the Indigenous activist Tracker Tilmouth is not written in Wright’s own words, but the words of others. It is, as the author points out, an attempt to capture the life of a man who communicated constantly, gave his ideas away freely, but never wrote anything down. Tracker, the “constantly travelling traditional song man”, is remembered by others “through the stories they kept telling about him”, and about his “ideas and dreams”. This is the way in which he touched lives and built communities.

Tracker is not an easy book. It is, as Wright states, an “impossible book”. It seeks to capture “the rare thing that does not want to be caught” – and perhaps cannot be caught. It is a book that needs to be read aloud in order to be experienced. It attempts to contain all the aspects of language and story that are left out when words get set down in patterns of black ink on a page.

![]() None of the books on the Stella shortlist offer a comforting vision of contemporary Australian life. And yet language illuminates, where ordinary life is dark and hazy.

None of the books on the Stella shortlist offer a comforting vision of contemporary Australian life. And yet language illuminates, where ordinary life is dark and hazy.

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor of Writing, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that considers the physical bookshop in the digital age.

For more visit:

https://groknation.com/culture/disappearing-bookstore-digital-age/

The link below is to an article that looks at the missing booksellers of Hong Kong.

For more visit:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/magazine/the-case-of-hong-kongs-missing-booksellers.html

Guillaume Thierry, Bangor University

English has achieved prime status by becoming the most widely spoken language in the world – if one disregards proficiency – ahead of Mandarin Chinese and Spanish. English is spoken in 101 countries, while Arabic is spoken in 60, French in 51, Chinese in 33, and Spanish in 31. From one small island, English has gone on to acquire lingua franca status in international business, worldwide diplomacy, and science.

But the success of English – or indeed any language – as a “universal” language comes with a hefty price, in terms of vulnerability. Problems arise when English is a second language to either speakers, listeners, or both. No matter how proficient they are, their own understanding of English, and their first (or “native”) language can change what they believe is being said.

When someone uses their second language, they seem to operate slightly differently than when they function in their native language. This phenomenon has been referred to as the “foreign language effect”. Research from our group has shown that native speakers of Chinese, for example, tended to take more risks in a gambling game when they received positive feedback in their native language (wins), when compared to negative feedback (losses). But this trend disappeared – that is, they became less impulsive – when the same positive feedback was given to them in English. It was as if they are more rational in their second language.

While reduced impulsiveness when dealing in a second language can be seen as a positive thing, the picture is potentially much darker when it comes to human interactions. In a second language, research has found that speakers are also likely to be less emotional and show less empathy and consideration for the emotional state of others.

For instance, we showed that Chinese-English bilinguals exposed to negative words in English unconsciously filtered out the mental impact of these words. And Polish-English bilinguals who are normally affected by sad statements in their native Polish appeared to be much less disturbed by the same statements in English.

In another recent study by our group, we found that second language use can even affect one’s inclination to believe the truth. Especially when conversations touch on culture and intimate beliefs.

Since second language speakers of English are a huge majority in the world today, native English speakers will frequently interact with non-native speakers in English, more so than any other language. And in an exchange between a native and a foreign speaker, the research suggests that the foreign speaker is more likely to be emotionally detached and can even show different moral judgements.

Read more:

Why native English speakers fail to be understood in English – and lose out in global business

And there is more. While English provides a phenomenal opportunity for global communication, its prominence means that native speakers of English have low awareness of language diversity. This is a problem because there is good evidence that differences between languages go hand-in-hand with differences in conceptualisation of the world and even perception of it.

In 2009, we were able to show that native speakers of Greek, who have two words for dark blue and light blue in their language, see the contrast between light and dark blue as more salient than native speakers of English. This effect was not simply due to the different environment in which people are brought up in either, because the native speakers of English showed similar sensitivity to blue contrasts and green contrasts, the latter being very common in the UK.

On the one hand, operating in a second language is not the same as operating in a native language. But, on the other, language diversity has a big impact on perception and conceptions. This is bound to have implications on how information is accessed, how it is interpreted, and how it is used by second language speakers when they interact with others.

We can come to the conclusion that a balanced exchange of ideas, as well as consideration for others’ emotional states and beliefs, requires a proficient knowledge of each other’s native language. In other words, we need truly bilingual exchanges, in which all involved know the language of the other. So, it is just as important for English native speakers to be able to converse with others in their languages.

The US and the UK could do much more to engage in rectifying the world’s language balance, and foster mass learning of foreign languages. Unfortunately, the best way to achieve near-native foreign language proficiency is through immersion, by visiting other countries and interacting with local speakers of the language. Doing so might also have the effect of bridging some current political divides.

![]()

Read more:

What will the English language be like in 100 years?

Guillaume Thierry, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Bangor University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.