The link below is to an article that takes a look at some names (and the story behind the names) that writers have given to their pets.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-stories-behind-15-of-the-best-names-famous-writers-gave-to-their-pets/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at some names (and the story behind the names) that writers have given to their pets.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/the-stories-behind-15-of-the-best-names-famous-writers-gave-to-their-pets/

The link below is to an article that reports on a report that found digital readers are more likely to be writers than print only readers. The article contains a link to the report concerned.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/digital-readers-are-more-likely-to-be-writers-than-print-only-readers-says-a-new-report/

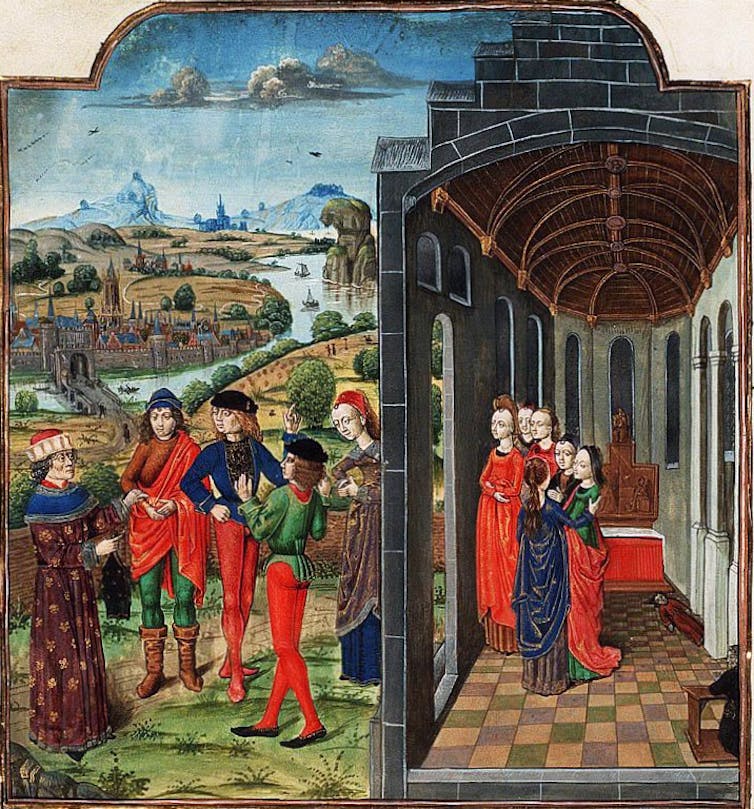

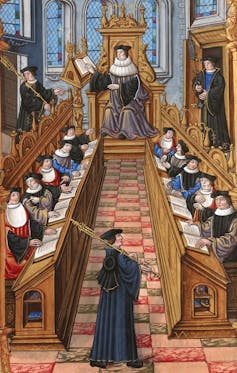

Kriston R. Rennie, The University of Queensland

A plague of serious proportions is ravaging the world. But not for the first time.

From 1347-51, the Black Death killed anywhere from one-tenth to one-half (or more) of Europe’s population.

One English chronicler, Thomas Walsingham, noted how this “great mortality” transformed the known world: “Towns once packed with people were emptied of their inhabitants, and the plague spread so thickly that the living were hardly able to bury the dead.” As death tolls rose at exponential rates, rents dwindled, and swaths of land fell to waste “for want of the tenants who used to cultivate it….”

As a medieval historian, I’ve been teaching the subject of plague for many years. If nothing else, the feelings of panic between the Black Death and the COVID-19 pandemic are reminiscent.

Like today’s crisis, medieval writers struggled to make sense of the disease; theories on its origins and transmission abounded, some more convincing than others. Whatever the result, “… so much misery ensued,” wrote another English author, it was feared that the world would “hardly be able to regain its previous condition.”

Medieval writers produced a variety of answers for the plague’s origins. Gabriele de Mussis’ Historia de Morbo attributed the cause to “the mire of manifold wickedness,” the “numberless vices,” and the “limitless capacity for evil” exhibited by an entire human race no longer fearing the judgement of God.

Describing its eastern origins, he further noted how the Genoese and Venetians had imported the disease to western Europe from Caffa (modern-day Ukraine); “carrying the darts of death,” disembarking sailors at these Italian port-cities unwittingly spread the “poison” to their relations, kinsmen and neighbours.

Containing the disease seemed nearly impossible. As Giovanni Boccaccio wrote about Florence, the outcome was all the more severe as those suffering from the disease “mixed with people who were still unaffected …” Like a “fire racing through dry or oily substances,” healthy persons became ill.

Possessing the power to “kill large numbers by air alone,” through breath or conversation, it was thought, the plague “could not be avoided.”

Scholars worked tirelessly to find a cure. The Paris Medical Faculty devoted its energies to discovering the causes of these amazing events, which even “the most gifted intellects” were struggling to comprehend. They turned to experts on astrology and medicine about the causes of the epidemic.

On the pope’s orders, anatomical examinations were carried out in many Italian cities “to discover the origins of the disease.” When the corpses were opened up, all victims were found to have “infected lungs.”

Not content with lingering uncertainty, Parisian masters turned towards ancient wisdom and compiled a book of existing philosophical and medical knowledge. Yet they also acknowledged the limitations in finding a “sure explanation and perfect understanding,” quoting Pliny to the effect that “some accidental causes of storms are still uncertain, or cannot be explained.”

Prevention was critical. Quarantine and self-isolation were necessary measures.

In 1348, to prevent the illness from spreading through the Tuscan region of Pistoia, strict fines were enforced against the movement of peoples. Guards were placed at the city’s gates to prevent travellers entering or leaving.

These civic ordinances stipulated against importing linen or woollen cloths that might carry the disease. Demonstrating similar sanitation concerns, bodies of the dead were to remain in place until properly enclosed in a wooden box “to avoid the foul stench which comes from dead bodies”; moreover, graves were dug “two and a half arms-lengths deep.”

Butchers and retailers nevertheless remained open. And yet a number of regulations were imposed so that “the living are not made ill by rotten and corrupt food,” with further bans to minimize the “stink and corruption” considered harmful to Pistoia’s citizens.

Authorities responded in different ways to the outbreak. Recognizing the plague’s arrival by ship, the people of Messina “expelled the Genoese from the city and harbour with all speed.” In central Europe, foreigners and merchants were banished from the inns and “compelled to leave the area immediately.”

These were severe measures, but seemingly necessary given the varied social reaction to plague. As Boccaccio famously recounted in his Decameron, the whole spectrum of human behaviour ensued: from extreme religious devotion, sober living, self-isolation and a restricted diet to warding off evil through heavy drinking, singing and merrymaking.

The fear of contagion eroded social customs. The number of dead grew so high in many regions that proper burials and religious services became impossible to perform: new religious customs emerged pertaining to preparing for and presiding over death.

Families were changed. An account from Padua mentions how “wife fled the embrace of a dear husband, the father that of a son and the brother that of a brother.”

Ultimately, there is a human element to plague too often lost in the historical record. Its influence should not be underestimated or forgotten. The modern response to pandemic evokes a similar community response. Different in scope and scale, and indeed in medical practice, administrative and public health actions remain critical.

But in 2020, we are not, as Boccaccio lamented, seeing the law and social order break down. Essential duties and responsibilities are still being carried out. Against our own 21st-century plague, wisdom and ingenuity are prevailing; citizens hang on “the advice of physicians and all the power of medicine,” which unlike the 14th century, is anything but “profitless and unavailing.”![]()

Kriston R. Rennie, Visiting Fellow at the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, Toronto, and Associate Professor in Medieval History, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nancy Kang, University of Manitoba

In Mules and Men (1935), anthropologist, creative writer and Harlem Renaissance upstart Zora Neale Hurston relays the evocative folktale “Why the Sister in Black Works Hardest.” Fatigued after the work of Creation, God casts a massive bundle onto the earth. Intrigued by the mysterious object, a white Southern woman during the antebellum era asks her husband to retrieve it. Reluctant to tote the load himself, the master instructs a slave to fetch it.

Soon wearied of the task, the slave then commands his wife to shoulder the burden. She does so, excited at the prospect of exploring the contents. When she opens the package, however, what leaps out at her and Black women for all posterity is none other than hard work.

African American women writers have tackled the hard work of representing a diverse spectrum of lived and imagined experiences, including and especially their own. This labour occurs against the backdrop of centuries-long struggles with racist oppression and gender-based violence, including — but not limited to — slavery’s culture of endemic rape, forced or interrupted motherhood, infanticide, concubinage, fractured families and egregious physical and mental abuse.

Renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass recalls in his 1845 slave narrative how witnessing the serial whippings of his Aunt Hester impacted him “with awful force.” He explains, “it was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass. It was a most terrible spectacle.”

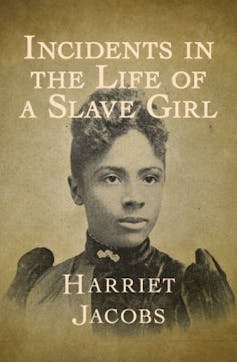

These ordeals also emerge in slave narratives by women. Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) emphasizes such travails. A target of relentless sexual harassment by her much-older master, Jacobs laments, “When they told me my new-born babe was a girl, my heart was heavier than it had ever been before. Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women.”

Once emancipated, African American women still faced staggering impediments when pursuing educational, entrepreneurial and employment opportunities. Political participation meant restrictions on voting rights both as women and as people of colour. Racist caricatures impugned everything from a woman’s intelligence and moral capacity to her skin color, texture of hair and body shape. Stereotypes like the docile Mammy, the Tragic Mulatta, the clownish Topsy, the oversexed Jezebel, the greedy Welfare Queen, the amoral Hoodrat and the Mad Black Woman (still prevalent today) remain testaments to a history of disrespect and erasure.

Hurston’s tale symbolizes the enduring social struggles Black women have faced living in what feminist critic bell hooks has termed white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

In addition to influential autobiographers like Maya Angelou, dramatists like Lorraine Hansberry and poets like Gwendolyn Brooks, fiction writers have consistently demonstrated how imaginative art can simultaneously inform, persuade, entertain, catalyze social change and address individual as well as collective concerns.

Here is a short list of pivotal texts by African American women from the past century. These writers are but a small sample of the artists and intellectuals whose output resisted the force of what contemporary feminist critic Moya Bailey has termed misogynoir, or the corrosive fusion of anti-Blackness and misogyny prevalent in popular culture today. These women have completed the groundwork — and hard work — of envisioning a more just, inclusive society going forward.

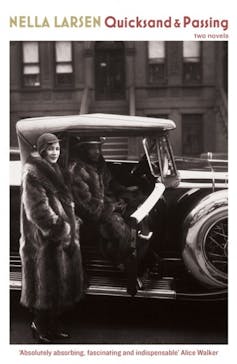

These novellas follow mixed-race women whose uneasy status on the colour line (including the lure of passing as white) complicates their lives in dangerous, even fatal ways. Passing is revolutionary for its depiction of homoerotic tension between two upper-middle-class Black women. Quicksand offers insight into the exoticization of African American women abroad and the contest between art and domesticity as viable avenues for a fulfilling life.

This story is the lyrical account of thrice-married Janie Crawford who finds a mature vision of love and fulfillment amid incessant gossip and a difficult family history. The all-Black township of Eatonville, Fla., and the rich “muck” of the Everglades contribute to a portrait of community health, daily striving and resolute self-awareness.

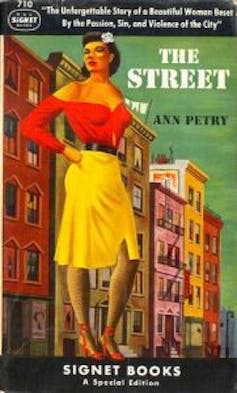

This social realist novel follows single mother Lutie Johnson as she attempts to make a life for her young son in a predatory urban space. Weathering sexism, racism, classism, poverty and intense personal frustration, Lutie attempts to resist the brutality of the environment that gives the novel its loaded name.

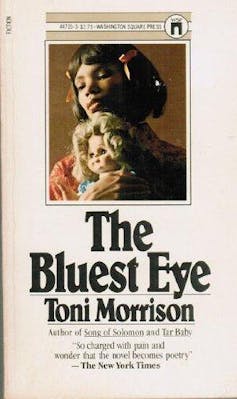

This book is a searing portrait of a young girl’s coming-of-age and eventual undoing in the years following the Great Depression. Tumultuous family dynamics, psychological trauma and incest, the quest for compassion and self-love, and the toxic myth of Black ugliness coalesce in this first novel by the Nobel Laureate and author of neo-slave narrative Beloved (1987).

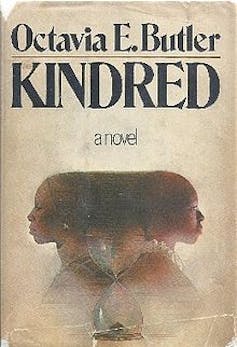

Oscillating between the 1970s and the early 19th century, this science fiction odyssey (re)connects a contemporary Black woman writer and her white husband with her ancestors on a Maryland plantation. The novel is buoyed up by the dramatic tension of time travel and the juxtaposition of the pre-civil War Antebellum-era with Civil Rights-era racial attitudes, including those about interracial love and allyship.

Structured like a narrative quilt, these interconnected experiences of seven women span different generations, professions, class backgrounds and understandings of their place in the world. The eroded apartment complex that links them is the backdrop for unbearable pain as well as the promise of transformation and reconciliation.

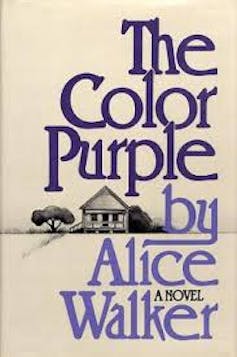

A tale of two sisters, Celie and Nettie, this novel constellates their love and longing via letters and imagined conversations across the Atlantic. Unsparing in its critique of domestic violence and toxic masculinity, yet tender in its treatment of various human weaknesses, the novel underscores Black women’s need for self-regard and mutual care. Not only are these acts revolutionary, but they also offer a glimpse of the divine.![]()

Nancy Kang, Assistant Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Transnational Feminisms and Gender-Based Violence, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Claire Hooker, University of Sydney and Ian Kerridge, University of Sydney

This is one of our occasional Essays on Health. It’s a long read.

It may seem paradoxical, but dying can be a deeply creative process.

Public figures, authors, artists and journalists have long written about their experience of dying. But why do they do it and what do we gain?

Read more:

On poetry and pain

Many stories of dying are written to bring an issue or disease to public attention.

For instance, English editor and journalist Ruth Picardie’s description of terminal breast cancer, so poignantly described in Before I say Goodbye, drew attention to the impact of medical negligence, and particularly misdiagnosis, on patients and their families.

American tennis player and social activist Arthur Ashe wrote about his heart disease and subsequent diagnosis and death from AIDS in Days of Grace: A Memoir.

His autobiographical account brought public and political attention to the risks of blood transfusion (he acquired HIV from an infected blood transfusion following heart bypass surgery).

Other accounts of terminal illness lay bare how people navigate uncertainty and healthcare systems, as surgeon Paul Kalanithi did so beautifully in When Breath Becomes Air, his account of dying from lung cancer.

But, perhaps most commonly, for artists, poets, writers, musicians and journalists, dying can provide one last opportunity for creativity.

American writer and illustrator Maurice Sendak drew people he loved as they were dying; founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud, while in great pain, refused pain medication so he could be lucid enough to think clearly about his dying; and author Christopher Hitchens wrote about dying from oesophageal cancer despite increasing symptoms:

I want to stare death in the eye.

Faced with terminal cancer, renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote, if possible, more prolifically than before.

And Australian author Clive James found dying a mine of new material:

Few people read

Poetry any more but I still wish

To write its seedlings down, if only for the lull

Of gathering: no less a harvest season

For being the last time.

Read more:

Vale Clive James – a marvellous low voice whose gracious good humour let others shine

Research shows what dying artists have told us for centuries – creative self-expression is core to their sense of self. So, creativity has therapeutic and existential benefits for the dying and their grieving families.

Creativity provides a buffer against anxiety and negative emotions about death.

It may help us make sense of events and experiences, tragedy and misfortune, as a graphic novel did for cartoonist Miriam Engelberg in Cancer Made Me A Shallower Person, and as blogging and online writing does for so many.

Creativity may give voice to our experiences and provide some resilience as we face disintegration. It may also provide agency (an ability to act independently and make our own choices), and a sense of normality.

French doctor Benoit Burucoa wrote art in palliative care allows people to feel physical and emotional relief from dying, and:

[…] to be looked at again and again like someone alive (without which one feels dead before having disappeared).

When someone who is dying creates a work of art or writes a story, this can open up otherwise difficult conversations with people close to them.

But where these works become public, this conversation is also with those they do not know, whose only contact is through that person’s writing, poetry or art.

This public discourse is a means of living while dying, making connections with others, and ultimately, increasing the public’s “death literacy”.

In this way, our conversations about death become more normal, more accessible and much richer.

There is no evidence reading literary works about death and dying fosters rumination (an unhelpful way of dwelling on distressing thoughts) or other forms of psychological harm.

In fact, the evidence we have suggests the opposite is true. There is plenty of evidence for the positive impacts of both making and consuming art (of all kinds) at the end of life, and specifically surrounding palliative care.

Some people read narratives of dying to gain insight into this mysterious experience, and empathy for those amidst it. Some read it to rehearse their own journeys to come.

But these purpose-oriented explanations miss what is perhaps the most important and unique feature of literature – its delicate, multifaceted capacity to help us become what philosopher Martha Nussbaum described as:

[…] finely aware and richly responsible.

Literature can capture the tragedy in ordinary lives; its depictions of grief, anger and fear help us fine-tune what’s important to us; and it can show the value of a unique person across their whole life’s trajectory.

Not everyone, however, has the opportunity for creative self-expression at the end of life. In part, this is because increasingly we die in hospices, hospitals or nursing homes. These are often far removed from the resources, people and spaces that may inspire creative expression.

And in part it is because many people cannot communicate after a stroke or dementia diagnosis, or are delirious, so are incapable of “last words” when they die.

Read more:

What is palliative care? A patient’s journey through the system

Perhaps most obviously, it is also because most of us are not artists, musicians, writers, poets or philosophers. We will not come up with elegant prose in our final days and weeks, and lack the skill to paint inspiring or intensely beautiful pictures.

But this does not mean we cannot tell a story, using whatever genre we wish, that captures or at least provides a glimpse of our experience of dying – our fears, goals, hopes and preferences.

Clive James reminded us:

[…] there will still be epic poems, because every human life contains one. It comes out of nowhere and goes somewhere on its way to everywhere – which is nowhere all over again, but leaves a trail of memories. There won’t be many future poets who don’t dip their spoons into all that, even if nobody buys the book.

Claire Hooker, Senior Lecturer and Coordinator, Health and Medical Humanities, University of Sydney and Ian Kerridge, Professor of Bioethics & Medicine, Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nancy Kang, University of Manitoba

In Mules and Men (1935), anthropologist, creative writer and Harlem Renaissance upstart Zora Neale Hurston relays the evocative folktale “Why the Sister in Black Works Hardest.” Fatigued after the work of Creation, God casts a massive bundle onto the earth. Intrigued by the mysterious object, a white Southern woman during the antebellum era asks her husband to retrieve it. Reluctant to tote the load himself, the master instructs a slave to fetch it.

Soon wearied of the task, the slave then commands his wife to shoulder the burden. She does so, excited at the prospect of exploring the contents. When she opens the package, however, what leaps out at her and Black women for all posterity is none other than hard work.

African American women writers have tackled the hard work of representing a diverse spectrum of lived and imagined experiences, including and especially their own. This labour occurs against the backdrop of centuries-long struggles with racist oppression and gender-based violence, including — but not limited to — slavery’s culture of endemic rape, forced or interrupted motherhood, infanticide, concubinage, fractured families and egregious physical and mental abuse.

Renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass recalls in his 1845 slave narrative how witnessing the serial whippings of his Aunt Hester impacted him “with awful force.” He explains, “it was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass. It was a most terrible spectacle.”

These ordeals also emerge in slave narratives by women. Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) emphasizes such travails. A target of relentless sexual harassment by her much-older master, Jacobs laments, “When they told me my new-born babe was a girl, my heart was heavier than it had ever been before. Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women.”

Once emancipated, African American women still faced staggering impediments when pursuing educational, entrepreneurial and employment opportunities. Political participation meant restrictions on voting rights both as women and as people of colour. Racist caricatures impugned everything from a woman’s intelligence and moral capacity to her skin color, texture of hair and body shape. Stereotypes like the docile Mammy, the Tragic Mulatta, the clownish Topsy, the oversexed Jezebel, the greedy Welfare Queen, the amoral Hoodrat and the Mad Black Woman (still prevalent today) remain testaments to a history of disrespect and erasure.

Hurston’s tale symbolizes the enduring social struggles Black women have faced living in what feminist critic bell hooks has termed white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

In addition to influential autobiographers like Maya Angelou, dramatists like Lorraine Hansberry and poets like Gwendolyn Brooks, fiction writers have consistently demonstrated how imaginative art can simultaneously inform, persuade, entertain, catalyze social change and address individual as well as collective concerns.

Here is a short list of pivotal texts by African American women from the past century. These writers are but a small sample of the artists and intellectuals whose output resisted the force of what contemporary feminist critic Moya Bailey has termed misogynoir, or the corrosive fusion of anti-Blackness and misogyny prevalent in popular culture today. These women have completed the groundwork — and hard work — of envisioning a more just, inclusive society going forward.

These novellas follow mixed-race women whose uneasy status on the colour line (including the lure of passing as white) complicates their lives in dangerous, even fatal ways. Passing is revolutionary for its depiction of homoerotic tension between two upper-middle-class Black women. Quicksand offers insight into the exoticization of African American women abroad and the contest between art and domesticity as viable avenues for a fulfilling life.

This story is the lyrical account of thrice-married Janie Crawford who finds a mature vision of love and fulfillment amid incessant gossip and a difficult family history. The all-Black township of Eatonville, Fla., and the rich “muck” of the Everglades contribute to a portrait of community health, daily striving and resolute self-awareness.

This social realist novel follows single mother Lutie Johnson as she attempts to make a life for her young son in a predatory urban space. Weathering sexism, racism, classism, poverty and intense personal frustration, Lutie attempts to resist the brutality of the environment that gives the novel its loaded name.

This book is a searing portrait of a young girl’s coming-of-age and eventual undoing in the years following the Great Depression. Tumultuous family dynamics, psychological trauma and incest, the quest for compassion and self-love, and the toxic myth of Black ugliness coalesce in this first novel by the Nobel Laureate and author of neo-slave narrative Beloved (1987).

Oscillating between the 1970s and the early 19th century, this science fiction odyssey (re)connects a contemporary Black woman writer and her white husband with her ancestors on a Maryland plantation. The novel is buoyed up by the dramatic tension of time travel and the juxtaposition of the pre-civil War Antebellum-era with Civil Rights-era racial attitudes, including those about interracial love and allyship.

Structured like a narrative quilt, these interconnected experiences of seven women span different generations, professions, class backgrounds and understandings of their place in the world. The eroded apartment complex that links them is the backdrop for unbearable pain as well as the promise of transformation and reconciliation.

A tale of two sisters, Celie and Nettie, this novel constellates their love and longing via letters and imagined conversations across the Atlantic. Unsparing in its critique of domestic violence and toxic masculinity, yet tender in its treatment of various human weaknesses, the novel underscores Black women’s need for self-regard and mutual care. Not only are these acts revolutionary, but they also offer a glimpse of the divine.![]()

Nancy Kang, Assistant Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Transnational Feminisms and Gender-Based Violence, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba, University of Winnipeg

During the massacre of Igbos in Nigeria between 1966 and 1970, one to three million people died. In the decades since, writers have worked to make sense of the immense human tragedy.

These literary representations of the massacres use the Holocaust as an important point of reference.

The war in Nigeria, with its associated mass atrocities, is arguably one of the first major moments in postcolonial Africa when accusations of genocide were made. Following military coups in Nigeria in 1966, the military and ethnic extremists systematically targeted and killed Igbos across the then Northern and Western regions of Nigeria.

Massacres of Igbos and other Easterners across the country led to thousands of deaths and the displacement of millions.

The massacres led the Eastern Region of Nigeria to declare its secession from Nigeria. The region was renamed the republic of Biafra. Nigeria invaded Biafra in July 1967, leading to a protracted war. The federal government used starvation tactics which led to upwards of three million civilian deaths in Biafra. Biafra officially surrendered to Nigeria in January 1970.

After its genocidal war, the Nigerian government proceeded to engineer a culture of denial.

To counter that propaganda, writers reflecting on that past have often framed the war as genocide. A common feature in the writings is the comparison of Igbo experiences of atrocities to Jewish ones during the Holocaust.

During the Biafran War, U.S.-based Igbo poet, Onwuchekwa Jemie, compared the murder of Igbos in Nigeria to the Nazi German murder of Jews during the Second World War. His poem, “Requiem” (from his 1970 poetry collection, Biafra: Requiem for the Dead in War) reflects this:

Once in 53

Three times in 66

Nigerians shoot civilians

through the ears

rehearsing all known tortures

murdering all males

and raping old women

forcing teenage girls in leper clinics

hundreds butchered…

the 30,000 innocents

mowed down Nazi fashion

a final solution

that failed again.

In “Requiem,” Jemie catalogues the systematic persecutions and murders of Igbo civilians, which he considers similar to the Nazis’ “final solution.”

The lines “a final solution / that failed again” encapsulate the poet’s defiant view that Biafra will survive the genocidal onslaught from Nigeria.

Global history scholar Lasse Heerten has explained in his work on Biafra, that such comparisons of Igbo suffering to the Nazi genocide of Jews reveal the growing awareness of the Holocaust in African conflict zones at the time.

The comparison of Igbo suffering to the Holocaust offers a way for the writers to internationalize Igbo experience in Nigeria. In so doing, they are sharing a moral message about the universal condition of human cruelty.

Similarly, the 1971 poem “Vultures” by Chinua Achebe reflects on the troubling realization that humans possess simultaneously a capacity for human care and a vulture’s inhumane savagery. The poet imagines a Nigerian military commander as a vulture and compares him to the Commandant of the Nazis’ death camp at Belsen:

Thus the Commandant at Belsen

Camp going home for

the day with fumes of

human roast clinging

rebelliously to his hairy

nostrils will stop

at the wayside sweetshop

and pick up a chocolate

for his tender offspring

waiting at home for Daddy’s

return…

Achebe’s reference to the Holocaust evokes the Nazi death camps as a site of savagery: “fumes of / human roast.” He seems to be alluding to Paul Celan’s 1948 poem, “Death Fugue,” which describes the cremation of Jewish victims in the Nazi camps as a “grave in the sky.”

Reference to the Holocaust in Achebe’s poem provides a way to meditate on the ironic condition of human cruelty.

Another writer who used the Holocaust as a metaphor for moralizing about the human condition is Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, who was jailed for his attempts to mediate between Biafra and Nigeria. His 1972 prison memoir The Man Died expresses his frustration over the unending cycles of brutality and the pattern of genocidal murders taking place in Nigeria. Soyinka’s other books, plays and poems on the 1966-1970 crisis equally draw on the Holocaust as a way to comment on cruelty.

Such comparison between Igbo suffering and the Holocaust intending to convey a moral message on human condition can be found in several other writings, including Flora Nwapa’s Never Again, Chris Abani’s Graceland (2004), Nnedi Okorafor’s fantasy novels, Who Fears Death (2010) and The Book of Phoenix (2015), and notably too in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, Half of a Yellow Sun (2006).

In Half of a Yellow Sun, there are several instances comparing the experiences of Igbos to those of Jews under the Nazis.

For example, the title of the character Ugwu’s story, ‘The World Was Silent When We Died,’ echoes the original Yiddish title of Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir, Un di Velt Hot Geshvign, (“And the World Has Remained Silent”).

I believe these literary analogies between Jewish and Igbo experiences have helped to make the atrocities public and known. However, these analogies can also overwhelm the particulars of the Nigerian context of the crisis.

Because the political contexts of such historical mass atrocities being compared vary significantly, these comparisons may come at the cost of our understanding of genocide in African states. Both African and European historical contexts within which these atrocities occurred may become de-territorialized and depoliticized.

In the meantime, local suppression of political questions of Igbo self-determination and justice in the war’s aftermath remain unaddressed.![]()

Chigbo Arthur Anyaduba, Assistant Professor, University of Winnipeg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rebecca Giblin, Monash University and Joshua Yuvaraj, Monash University

Who makes the money in publishing? Nobody. This often repeated dark joke highlights a serious issue. The most recent figures show that Australian authors earn just $12,900 a year from writing work (the median, at $2,800, was even worse). Indeed, authors can gross less than $5,000 for Miles Franklin-nominated titles that took two or more years to write.

Fixing this isn’t as simple as reaching more deeply into publisher pockets, because most of those are empty too. While the major international houses are thriving (Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House recently reported 16% profits), publishing Australian stories can be financially perilous.

In independent publishing, 10% of the book sale goes to the author, perhaps another 10% to the printer, and up to a whopping 70% for distribution. What’s left has to pay the publisher, editor, marketers, admin staff and keep the lights on.

But we can improve our approach to author rights. Here are five lessons we can learn from elsewhere to help Australian writers earn more money.

Read more:

Scrounging for money: how the world’s great writers made a living

Traditionally, contractual “out of print” clauses have let authors reclaim their rights when a print run has sold out and the publisher doesn’t want to invest in another. But in our recent analysis of almost 150 contracts in the Australian Society of Authors archive, we found 85% of contracts with these clauses allowed authors to reclaim their rights only when the book was “not available in any edition”.

These days, books can be kept available (at least digitally or via print-on-demand) forever – but that doesn’t mean their publishers are still actively promoting them.

A better approach is to allow authors to reclaim their rights towards the end of a work’s commercial life, determined with reference to objective criteria like the number of copies sold or royalties earned in the previous year. The Australian Society of Authors recommends authors only sign contracts that have this meaningful kind of out-of-print clause – but many publishers still try to get authors to sign up to unacceptable terms.

Read more:

How to read the Australian book industry in a time of change

A growing number of countries (including France, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Macedonia and Brazil mandate author rights based on objective criteria. The French law is an interesting model. There, authors can get their rights back if a book has been published for at least four years, and they haven’t been credited royalties for at least two. This opens up new possibilities for the author to license it to another publisher, or even sell it directly to libraries or consumers.

Publishers take very broad rights to most books: in our recent archival analysis we found 83% took worldwide rights, and 43% took rights in all languages. It’s easy to take rights – but if publishers do so, they should be obliged to either use them or give them back.

To that end we can learn from the “use it or lose it” laws that bind publishers in some parts of Europe. In Spain and Lithuania, for example, authors can get their rights back for languages that are still unexploited after five years.

Of course, it’s not always the case that there’s no money in publishing: sometimes a title that was expected to sell 5,000 copies sells 5,000,000. That changes the economics enormously: but in many cases, the contract only provides the same old 10% revenue for the author. For works that achieve unexpected success, we can learn from Germany and the Netherlands (and the proposed new EU copyright law). They have “bestseller” clauses that give authors the right to share fairly in unexpected windfalls arising from their work.

Even where there’s not much money to be made, the author should still receive a fair share. Again, Germany and the Netherlands lead the way on this. There, authors are entitled to “fair” or “equitable” payment for their work – and can enforce those rights if their pay is too low.

These laws don’t set a dollar amount, since what is “fair” depends on all the circumstances. However, such laws at least provide a minimum floor. If the contracted amount is unfair or inequitable, authors have a legal right to redress.

In Australia, copyright lasts for the life of the author, and then another 70 years after that. Publishers almost always take rights for that full term – only 3% of the contracts between publishers and authors we looked at took less. But publishers don’t need that long to recoup their investments. In the US, authors can reclaim their rights from intermediaries 35 years after they licensed or transferred them.

In Canada, copyrights transfer automatically to heirs 25 years after an author dies. We used to have the same law in Australia, but it was abolished for spurious reasons about 50 years ago. If we reintroduced a similar time limit on transfers, it would open up new opportunities for authors and their heirs (for example, to license or sell to a different publisher, libraries or direct to the public).

It’s true that there’s often not much money in publishing. But by changing our approach to author rights, we can help writers earn more and make Australian books more freely available.![]()

Rebecca Giblin, ARC Future Fellow; Associate Professor, Monash University and Joshua Yuvaraj, PhD Candidate, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at 5 free design tools for writers.

For more visit:

https://indiereader.com/2018/11/5-free-and-awesome-design-tools-for-writers/

The link below is to a list of 10 rules for novelists – which should provoke ‘some thoughts.’

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/jonathan-franzens-10-rules-for-novelists/

You must be logged in to post a comment.