The link below is to an article that reports on the removal of the Value Added Tax from ebooks in the UK.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/03/12/uk-to-end-vat-on-ebooks-but-not-audiobooks/

The link below is to an article that reports on the removal of the Value Added Tax from ebooks in the UK.

For more visit:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2020/03/12/uk-to-end-vat-on-ebooks-but-not-audiobooks/

Nicola Wilson, University of Reading

These are unprecedented times – but, even so, comparisons are being made to the second world war in terms of the magnitude of the crisis that coronavirus represents. Some of this rhetoric is unhelpful but, as we bunker down into our homes and the government gets on a war footing, there is little doubt that the challenge to our liberty, leisure time and sense of wellbeing is real.

With early reports that book sales are soaring while bookshops and warehouses close down and publishers reassess their lists, what can the reading patterns of an earlier generation tell us about getting through a crisis and staying at home?

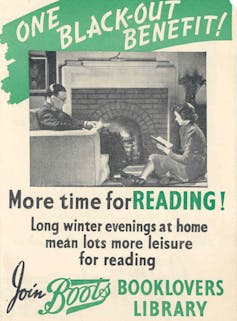

The restrictions at the beginning of the second world war affected all aspects of day-to-day life. But it was the blackout that topped most people’s list of grievances – above shortages of food and fuel, the evacuation, and lack of news and public services. Households were reprimanded and fined for showing chinks of light through windows, car lights were dimmed, and walking around, even along familiar streets, late at night became treacherous.

With the widespread limitations to free movement, the book trade was quick off the mark. Books were promoted by libraries and book clubs as the very thing to fight boredom and fill blacked-out evenings at home or in shelters with pleasure and forgetfulness. “Books may become more necessary than gas-masks,” the Book Society, Britain’s first celebrity book club, advised.

I’ve been researching the choices and recommendations of the Book Society for the past few years. The club was set up in 1929 and ran until the 1960s, shipping “carefully” selected books out to thousands of readers each month. It was modelled on the success of the American Book-of-the-Month club (which launched in 1926) and aimed to boost book sales at a time when buying books wasn’t common. It irritated some critics and booksellers who accused it of “dumbing down” and giving an unfair advantage to some books over others – but was hugely popular with readers.

The Book Society was run by a selection committee of literary celebrities – the likes of JB Priestley, Sylvia Lynd, George Gordon, Edmund Blunden and Cecil Day-Lewis – chaired by bestselling novelist Hugh Walpole. Selections were not meant to be the “best” of anything, but had to be worthwhile and deserving of people’s time and hard-earned cash.

Guaranteeing tens of thousands of extra sales, the club had a huge impact on the mid-20th-century book trade, with publishers desperate to get the increased sales and global reach of what publisher Harold Raymond called “the Book Society bun”.

The Book Society guided readers through the confusion of appeasement and the run-up to the second world war with a marked increase in recommendations of political non-fiction examining contemporary geo-politics. The classic novel of appeasement was Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart (Book Society Choice in October 1938) in which a sense of malaise and inevitability of future war haunts the characters’ desperate actions.

When Britain finally declared war against Germany in September 1939, the Book Society judges were divided. Some were relieved that, as George Gordon put it, “an intolerable situation has at last acquired the awful explicitness of war”. But others were devastated, especially Edmund Blunden who was still traumatised from fighting in the first world war.

The judges advised members that when they became weary of news, people “will turn to books as the best comfort”, as had happened in the first world war with the increase in reading and library membership. Publishers and booksellers faced huge challenges during the second world war, including paper shortages, problems in distribution, a vanishing workforce, and bomb damage to offices and warehouses. But there were more readers – and from a wider social class – at the end of it. Demand consistently outstripped supply as consumer expenditure on books more than doubled between 1938 and 1945.

Throughout the second world war, the Book Society varied its lists between books that offered some insight on the strangeness of contemporary life and works of fiction – especially historical fiction – that took readers’ minds off it.

Titles in the first group include comic novels by the likes of E M Delafield and Evelyn Waugh, as well as forgotten bestsellers like Ethel Vance’s Escape (1939) (an unlikely thriller set in a concentration camp) and Reaching for the Stars (1939), American journalist Nora Waln’s inside account of life in Nazi Germany.

More topical non-fiction became a priority as the devastation of the Blitz kicked in. Winged Words: Our Airmen Speak for Themselves (1941) and Into Battle: Winston Churchill’s War Speeches (1941) were especially popular.

Historical fiction was consistently in demand. Half the club’s choices in 1941 were long novels with historical settings. As today’s readers prepare to batten down the hatches with Hilary Mantel’s 900-page latest book, it is sobering to reflect on how an imaginative connection with the past has long helped readers find relief from the madness of the present.

Read more:

The Mirror and the Light: Hilary Mantel gets as close to the real Thomas Cromwell as any historian

The other fail-safes in the second world war were the classics. As books already in print became scarce, the Book Society reissued new editions of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karenina. These were books that Walpole said he believed he could sit down with even through an air raid.

Indeed, Neilsen BookScan has reported a rise in sales of classic fiction as the coronavirus crisis deepens – including War and Peace – as readers use this unfamiliar time to knuckle down to the heavyweights.

You can also join a War and Peace reading group online if you want a bit of company. After the homeschooling, working from home, and everything else. Here goes.![]()

Nicola Wilson, Associate Professor in Book and Publishing Studies, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thomas McLean, University of Otago

In revealing the charms and follies of genteel English society, Jane Austen has few competitors. Yet as Britain limps towards Brexit, I can’t help wondering why there are no foreigners in her major fiction. Many thousands of continental Europeans settled in Britain after the French Revolution and during the Napoleonic wars. Couldn’t just one of the Bennet sisters have fallen in love with a charming Belgian or a wealthy German? Wouldn’t the well-travelled Frederick Wentworth of Persuasion have a dear friend from Spain or Italy?

Such questions may seem trivial, but they gain significance at a time when we expect a lot from Austen. In the past few decades, scholars have regularly turned to her novels for insights into the larger issues of her era (women’s education, slavery, war) and our own (climate change). Some even want to see her as a radical.

I’m not so convinced by this progressive – or even subversive – Austen. She was unquestionably sensitive to the epoch-defining events taking place around her. Two of her brothers were officers in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars; another was a banker who was ruined in the post-war financial crisis. Certainly, there are moments in the novels when these larger events make an appearance. How could they not?

Read more:

Jane Austen’s curious banking story makes her an apt face for the £10 note

But are such moments enough to make Austen’s works a source of great insight into the social issues of her era? In matters of love, friendship and the societal expectations of the landed gentry, Austen is always astute and entertaining. But consider all the elements of her society that Austen left out.

Are there, for instance, any Catholics in Austen’s novels? Any Jews? Mark Twain wrote that Austen’s novels made him feel like a “barkeeper” surrounded by “ultra-good Presbyterians” – but are there any actual Presbyterians in her novels? So far as I can tell, all of her principal characters are Anglican.

Are there any foreigners – a Frenchman, say, or a visiting Spaniard? Nope. Northanger Abbey mocks the English affection for gothic novels set on the continent, but no one from the continent appears in the novel. In a scene from Emma that Priti Patel might applaud, Frank Churchill rescues Harriet Smith from a group of “loud and insolent” Romany children.

How about representatives from other parts of the UK? In Austen’s novels, Scotland is mainly a place to which giddy young women elope. As for Wales, well, there’s a “Welch cow” in Emma. Ireland does a little better: in Pride and Prejudice, Mary Bennet annoys her sister by playing Irish songs on the piano; and in Emma, an honest to goodness Irishman, one Mr Dixon, plays a minor role – though, like so many other male characters in Austen’s novels, he isn’t important enough to earn a first name.

Austen is deservedly recognised for bringing greater realism to the Anglophone novel and for presenting a new psychological depth in her characters. Yet this position should not be confused with the idea that Austen somehow tells us more about Regency England than any of her contemporaries – or that her works contain all the complexities of her era if only we look closely enough. They tell us very little about the way the English looked on their British and European neighbours.

I hear you ask, well come now, you don’t really expect a Regency-era author to include foreigners, revolutionaries and exiles in her novel, do you? Well, yes, actually I do. Many of Austen’s forgotten contemporaries – writers like Charlotte Smith, Frances Burney, and Maria Edgeworth – did just that. Another more famous contemporary, Mary Shelley, created the era’s greatest study of an outsider ostracised by society, Frankenstein. If we imagine that Austen provides a complete picture of Regency life, these authors prove us wrong with their more international and political perspectives.

This is not to say that they are better writers than Austen. Reading Austen’s contemporaries illuminates what makes Austen a great (in many ways superior) writer. Austen is utterly in command of the order and organisation of her best narratives – every character, every encounter, every character foible is there for a well-planned purpose.

Similarly, Austen’s protagonists are true to themselves. It is rare indeed for a reader to feel that her characters act in ways that were not foreseeable from the start. Her narrators keep a respectable distance from the action of the story: they provide enough information to leave readers feeling secure, but they rarely call attention to themselves or comment at length on the unfolding action. In all of these aspects, Austen has no Regency-era peer.

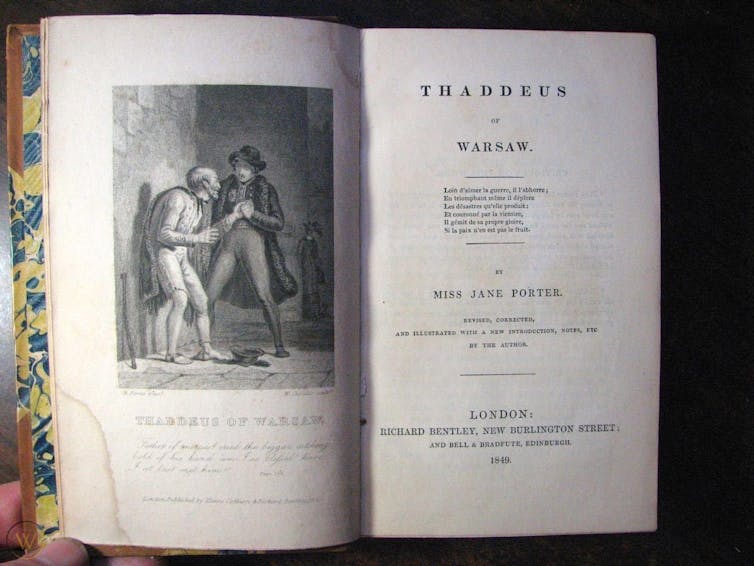

Nevertheless, some of these forgotten works illustrate the storytelling pathways that Austen never attempted. If I were to choose one work from Austen’s time that speaks most clearly to our own moment and showcases all that Jane left out, it would be Jane Porter’s novel from 1803, Thaddeus of Warsaw. Porter’s novel was a great success when it first appeared, and it remained in print for most of the 19th century.

Thaddeus – an early 19th-century forerunner to Walter Scott’s Waverley and William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair – tells the story of Count Thaddeus Sobieski, who escapes to Britain after his homeland falls to Russian invaders. Penniless, he hides his identity and makes his way among the rich and poor of London, finding work where he can, and coming to the aid of those less fortunate than he. He is befriended by a group of women, who assist or punish him, according to their impulses.

Imagine a Jane Austen novel with a Polish protagonist. Imagine an Austen novel where British women welcome an immigrant into their lives. Imagine an Austen novel where a character goes looking for work.

The passages in Thaddeus that resonate the most today, however, are the commentaries by British characters who are troubled by the presence of Polish exiles, like Thaddeus, among them. One character announces, “it is our duty to befriend the unfortunate; but charity begins at home … and, you know, the people of Poland have no claims upon us”. Another declares, “Would any man be mad enough to take the meat from his children’s mouths, and throw it to a swarm of wolves just landed on the coast?” No question that these characters would have voted “Leave”.

Today there are almost one million people living in the UK who were born in Poland. No matter what happens with regard to Brexit, these people have already changed their adopted homeland. While writers like Agnieszka Dale and Wioletta Greg create a new body of Anglo-Polish literature, Thaddeus of Warsaw reminds readers of the long links between the two countries.

It also reminds us that a satisfying romance, whether it concerns Emma Woodhouse or Thaddeus Sobieski, needs to please its readers. It won’t be giving too much away to note that, at the conclusion of Thaddeus of Warsaw, the meeting of wealth and love allows for a happy ending. That was one lesson that Jane Austen taught us a long time ago.![]()

Thomas McLean, Associate Professor, English and Linguistics, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Karen Sands-OConnor, Newcastle University

Cuddling up in a big chair with a good book, either with a familiar adult reading to you or starting the first chapter of a book on your own is a fundamental part of childhood – emotionally as well as intellectually. Reading about people who are like yourself affects both your self-image and the likelihood you will enjoy reading. Becoming a habitual reader, in turn, affects your life options. Reading about people different from yourself also encourages empathy and cultural understanding.

But if the world of children’s books doesn’t include people who look like you, it is difficult to feel welcomed into reading, as the writer Darren Chetty, among others, has pointed out. And recent research suggests that child readers, especially, but not exclusively, readers of colour, are being seriously shortchanged.

There simply aren’t enough authors and illustrators from diverse backgrounds being published, as academic Melanie Ramdarshan Bold pointed out in the 2019 Book Trust report on representation of people of colour among children’s book authors and illustrators. In fact, between 2007 and 2017, fewer than 2% of children’s book creators were British people of colour.

Authors of colour often feel isolated within the publishing industry. They are frequently encouraged to focus on racism and similar problem narratives, a recent report from Arts Council England (ACE) found. They do not have the freedom (as many white British authors do) to write across the broad spectrum of children’s literature genres if they want to be published.

While about a third of school-age children come from a minority ethnic background, the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education found that only 7% of children’s books published in Britain in 2018 had a Black, Asian or minority ethnic character. With so few diverse children’s books being published, these books are deeply important.

When characters of colour appear in children’s books, they are rarely the protagonist with the agency to effect change. Recent books sometimes still depict characters of colour as “sidekicks” who support and affirm the white main character. Other times, the “diversity” in a book appears in the background only.

Characters are defined by their colour, which makes them irreconcilably “other”. Descriptive words of character features compare them to food or animals. Sometimes characters appear early on in a narrative, only to quickly disappear in favour of a refocus on the white character. These techniques can dehumanise people of colour.

Children’s nonfiction, including history and science, either ignores contributions of people of colour to British society or pigeonholes particular ethnic groups into certain spaces only – such as the history of British slavery (and very specifically not the history of Afro-Caribbean uprisings against British slavery).

In a single children’s book, this “sidelining” of people of colour may not matter. However, when it is the enduring norm, as Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie stressed in her 2009 Ted talk on the danger of a single story, it situates readers of colour on the sidelines, too. This affects the reader’s perception of who matters in books.

While it would be easy to suggest that the problem lies with the British publishing industry alone, this is too simplistic. All people involved with children’s books need to participate in changing the narrative so that the books being published better represent the population and encourage all children to become readers, according to the ACE report.

This can be done in a variety of ways, and involves committed effort. Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books, began dedicating some of its collecting efforts to culturally diverse children’s literature in 2015. This has resulted in the acquisition of materials relating to children’s books by the Guyanese-born British poets John Agard and Grace Nichols in 2019. The acquisition of diverse materials by a national museum is one way of indicating the importance of this material to Britain and to British children’s literature.

Another way of highlighting the critical importance of including all children in children’s books is through awards. The longest-running children’s book prizes, the Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medal, have never been awarded to a British author of colour. Following the commissioning of a diversity review of the Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medal, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) revised the judging criteria for the annual prizes. These new guidelines ask judges to consider representation within books as they are making selections. Other children’s book prizes, including the Little Rebels prize, focus on children’s literature that challenges the status quo in areas such as diversity.

These efforts, large and small, bring attention to children’s books with characters of colour that might otherwise slip under the book-buying public’s radar. And getting librarians, educators and parents, no matter what their ethnic, racial or cultural background, to buy books is critical.

Publishing is a market-driven industry. If books aren’t selling, publishers can make the case that there is no audience and therefore they do not need to publish more books with characters of colour. All children need to feel welcome in the book world, and all children need to understand the diversity of British society now and throughout history.![]()

Karen Sands-OConnor, British Academy Global Professor, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shareena Z Hamzah, Swansea University

In 1605, England’s parliament was sitting on a powder keg, literally. Like now, the country was bitterly divided between two factions, with religion at the heart of the schism after the Reformation pitted Protestants and Catholics against each other in a life or death struggle. History tells us that instead of seeking a political solution such as an election, a group of 13 Catholic conspirators plotted to blow up parliament.

The conspiracy aimed to assassinate King James I and the Protestant establishment with a massive explosion under the House of Lords. Every “fifth of November” since then, what is now known as the Gunpowder Plot is remembered in Britain through bonfires, fireworks and the burning of effigies of one of the conspirators, Guido (Guy) Fawkes. Following the torture and execution of Fawkes and his co-conspirators, accusations of treason, heresy, and witchcraft were used to persecute many of the perceived enemies of the crown.

The process of arrest, torture, trial and execution was widespread, as the king sought to rid the country of his twin hatreds: Catholicism and witchcraft. This purge caused many Catholics, especially priests, to flee northwards to escape the king’s revenge. Lancashire came to be perceived by the royal court as a lawless area where Catholicism and witchcraft thrived – and it was there that the infamous Pendle witch trials of 1612 took place.

Though evidence remains from the actual trials, one of the most intriguing accounts didn’t come until 400 years after the events, when author Jeanette Winterson published her work of fiction, The Daylight Gate. In this story, the fates of a group of vagrant women and a Catholic nobleman, Christopher Southworth, converge when the attention of the law turns towards them. Winterson uses the genuine names of the women who were tried for witchcraft – though freely fictionalising their lives. Southworth was also a real person, a Jesuit priest from one of the oldest families in Lancashire.

As in real life, the women in the novel are charged with murder by witchcraft. Whether they committed acts of witchcraft or not, that is not their true crime here. These women have too much power and liberty for the patriarchal Protestant society in which they live. Southworth, meanwhile, is hunted in the novel for his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot. Captured previously, he had escaped from prison and fled to France, before returning to England to save his sister from her own witch trial.

There is no evidence to show the real Southworth was a part of the Gunpowder Plot. But historical record shows us Southworth was accused of coaching a young girl to make false accusations of witchcraft against her family – possible because the family had renounced Catholicism and converted to Protestantism. Given this, it’s likely he would have supported at least the aims of the Gunpowder Plot.

The fictional women’s bodies are sites onto which the men of the law project both their fears and desires. “Look her over for the witch marks – go on, Robert, run your hands across her. Do you like her breasts?”, remarks a constable’s assistant. But these are bodies made monstrous by the effects of poverty. The feet of the appropriately named Mouldheels are described as stinking “of dead meat … wrapped in rags and already beginning to ooze”. Yet despite this monstrosity, these women are still raped by their captors as desire, disgust and domination merge.

Southworth’s status in the novel is initially different from the women. He was born and raised with the twin privileges of being male and wealthy. With no marks on his body to denote his Catholic faith, he could not be identified as an “other” without specific knowledge of his religious divergence from the ruling class. But, following the failed Gunpowder Plot, his torture at the hands of the king’s jailers results in his body being made monstrous. Attempts to blind Southworth leave scars on his eyelids and cheeks, and pictures are carved into his chest with knives.

Like the women, he is raped by his jailers. He is then literally emasculated when his penis and testicles are cut off. Perhaps luckily for the real-life Southworth, there is no evidence of an arrest, although his historical records are very scant. By comparison, the archives indicate the torture of Fawkes at the hands of the king’s inquisitors.

In this febrile, paranoid society of post-Gunpowder Plot England, the connection between Catholics and witches is stated explicitly. As Potts, the prosecutor sent by the royal court to seek out heretics, says: “Witchery popery, popery witchery. What is the difference?”. The outcomes are certainly very similar. And the burning of the womens’ bodies after their execution mirrors the ritual bonfires and immolation of Guy Fawkes effigies that have celebrated the failure of the Catholic plotters ever since.

Winterson’s novel forces the reader to consider what a monster is and what they might look like. Elizabeth Device, one of the supposed witches, is described as follows: “The strangeness of her eye deformity made people fear her. One eye looked up and the other looked down, and both eyes were set crooked in her face.” But her disfigured appearance had not saved her from being raped nine years before the novel’s setting. Throughout the book, fear and disgust mix dangerously with desire and power to produce awful crimes.

The real monsters are the men who savagely abuse and oppress the unfortunate – whether women or Catholics. Yet, they are not represented as physically repulsive. One of the torturers even has a “pleasant voice” as he questions his victims. In the end, The Daylight Gate reveals that monstrous desires produce and prey on monstrous bodies, and all those subjected to the burning heat of the king’s revenge eventually turn to ash. While the political situation in Britain today has moved away from the Catholic/Protestant schism of 1605, it is worth remembering the human tragedies behind the celebration of Bonfire Night.![]()

Shareena Z Hamzah, Honorary Research Associate, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that reports on sales figures for books/ebooks/audiobooks in the United Kingdom for 2018.

For more visit:

https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/uk-ebook-sales-have-increased-by-5-in-2018

The link below is to an article that reports on book/ebook/audiobook sales in the United Kingdom – the big winner? Audiobooks.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jun/26/new-chapter-uk-print-book-sales-fall-while-audiobooks-surge-43

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the United Kingdom’s 2019 Society of Authors Award winners.

For more visit:

https://publishingperspectives.com/2019/06/uk-society-of-authors-honor-32-writers-prize-fund-100000/

Rhea Seren Phillips, Swansea University

Poetry has played an important role in the history of Wales. From the medieval courts, to the ongoing National Eisteddfod (the largest music and poetry festival in Europe), writers have used verse to document the land’s culture. But while male writers, such as the 12th century poets of the princes and more recently Dylan Thomas, have presented one perspective of Welsh history and culture, female poets have documented a very different take on Wales through the centuries. Here are four who bring a different perspective.

Gwerful Mechain is one of the few Welsh medieval poets from whom a substantial body of work has survived to this day. One of the loudest voices speaking up for women of the time, Mechain was also one of the first poets in Wales to write about domestic abuse. To Her Husband for Beating Her is a poignant and powerful poem full of enraged language and energetic imagery.

Born into a noble family, Mechain was free to explore her own poetic interests without the pressure of securing patronage, unlike many of her male contemporaries. She became a prolific writer who was not restricted to one style. Her work includes religious, humorous and socially conscious poetry. One of her most well-known works, To the Vagina, chastises her male counterparts for praising a woman’s body from her hair to her feet but ignoring one hidden feature. She was bold and did not shy away from what some may consider crude imagery, as in her poem, To the Maid as she Shits.

This extract, in Welsh then English, is from Cywydd y cedor (The Female Genitals):

Pob rhyw brydydd, dydd dioed,

Mul frwysg, wladiadd rwysg erioed,

Noethi moliant, nis gwarantwyf,

Anfeidrol reiol, yr wyfEvery poet, drunken fool,

Thinks he is just the king of cool,

(Everyone is such a boor,

He makes me so sick, I’m so demure)

Born in London, Katherine Philips – who later wrote under the moniker “The Matchless Orinda” – moved to Wales when she was around 15 years old. From her home in Cardigan she became a significant female British poet, as well as the first woman to have a commercial play staged, Pompey.

Despite the stigma against women publishing their work, Philips succeeded by circulating handwritten letters and volumes, as her male contemporaries did, while upholding supposedly feminine virtues such as humility and chastity in her works.

Though she was married with two sons, much discussion around Philips’ poetry and life concentrates on whether she was or was not a lesbian. The emotional focus of her poetry was often on women and the passionate relationships she had with them. Regardless of Philips’ own sexual orientation, her work was the first British poetry to express same-sex love between women.

Sarah Jane Rees (also known by the bardic name Cranogwen) is perhaps one of the most pioneering poets in this list. Born in Llangrannog, west Wales, she spurned all attempts to enforce gender stereotypes – her family wanted her to work as a dressmaker – and instead joined her father on board his ship for two years after leaving school. She continued her education, eventually gaining her master mariner certificate. Returning home by the age of 21, Cranogwen fought against opposition to run her old school, and taught children as well as providing navigation and seamanship education to young men.

In 1865 she entered the Eisteddfod festival as Cranogwen with

Y Fodrwy Briodasal (The Wedding Ring), a satirical poem about a married woman’s destiny. When she was announced as the first woman to win the prize, there was disgust from the established and renowned male writers who had been competing. Cranogwen became famous overnight and a collection of her poems was released in 1870.

The following lines are taken from My Friend:

Ah! Annwyl chwaer, ‘r wyt ti i mi,

Fel lloer I’r lli, yn gyson;

Dy ddilyn heb orphwyso wna

Serchiadau pura’m calonOh! My dear sister, you to me

As the moon to the sea, constantly,

Following you restlessly are

My heart’s pure affections

Lynette Roberts was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina to parents of Welsh origin. A friend of Dylan Thomas, during World War II Roberts moved to Carmarthenshire with her then husband, journalist and poet Keidrych Rhys, and stayed in Wales for the rest of her life.

Although now her work is seeing a resurgence, for a long time Roberts has been overlooked. She was a poet ahead of her time and her use of language is refreshing. Roberts was influenced by the rich colours and landscape of her childhood, which she entwined with the rural landscape and culture of Wales during a time of upheaval – World War II.

Roberts’s poem Swansea Raid is perhaps one of her most powerful and insightful works. It depicts a snapshot of a relationship between herself and fellow villager Rosie and the tension between war and home. The changing technological world of war brought out warm, colourful language in her work, setting the colloquialisms of quiet, rural Wales against the starkness of bombing and constant threat of loss. Her most influential work has to be the heroic poem Gods with Stainless Ears, on the war’s disruption of domestic life.

This verse is from Roberts’ 1944 Poem from Llanybri:

Then I’ll do the lights, fill the lamp with oil,

Get coal from the shed, water from the well;

Pluck and draw pigeon, with crop of green foil

This your good supper from the lime-tree fell.

Rhea Seren Phillips, PhD Researcher in Welsh Poetry, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sarah Lawson Welsh, York St John University

Prize-winning British novelist Andrea Levy, who died on February 14, will be remembered affectionately for raising awareness of black British writing and the closely intertwined histories of Britain and the Caribbean more than any other British writer of recent times (save perhaps Zadie Smith). In a career spanning 25 years, during which she published five novels (two of which were successfully adapted for television) and a luminous collection of short stories and essays – a significant legacy in itself – Levy garnered an unusually wide readership which crossed literary, popular and academic lines.

Like Angela, the protagonist of her first, semi-autobiographical novel, Every Light in the House Burnin’ (1994), Levy was of Jamaican parentage, her father being one of the original Windrush passengers arriving in Britain in 1948, her mother following shortly after. Levy herself grew up in a working-class household with few books, recalling in characteristically frank terms that “being a working-class girl I mainly watched telly”.

Like Faith, the protagonist of her third novel, Fruit of the Lemon (1999), Levy knew little about her heritage and took little interest in Caribbean history and culture until a startling experience in a Racism Awareness training session at work launched her on a journey of rediscovery. As Faith’s mother says: “Child, everyone should know where they come from.”

Levy’s meticulously researched fictions interrogate the human experience of migration to and from the Caribbean in different periods. In Small Island (2004), Levy explores the ways in which Caribbean people were racially “othered” and made to feel unwelcome outsiders in Britain, despite being invited to migrate as British subjects in the post-1945 period.

In her final novel, The Long Song (2010), Levy harnesses fiction to, in her words, “go farther” – imaginatively excavating the human experiences of slavery from a variety of perspectives. Later on, in a twist stranger than fiction, Levy discovered that she herself, like her fictional character Miss July, was descended from a mixed-race liaison between a slave and a white overseer.

Although happy to be termed a black British writer, Levy importantly always saw the long historical connection between Britain and the Caribbean as a profoundly British concern, rather than a niche interest only relevant to those of Caribbean heritage. Indeed, reading her nuanced and inclusive explorations of what it is to be British and of Caribbean heritage might be seen as more urgent than ever in these heated times of Brexit and the Windrush scandal.

Levy started to write only in her 30s – but her writing achieved that rare thing: critical acclaim and commercial success (notably after Small Island which won the Orange Prize for Fiction, the Whitbread Book of the Year and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize). Her texts now have a place on academic curricula across the globe but also – crucially – a huge popular readership as her books fill a permanent place on ordinary peoples’ bookshelves.

As the many tributes from her readers, those who worked with her and from prominent black British figures such as Sir Lenny Henry testify, it is clear that Levy’s writing played a hugely important role in helping many readers learn about, connect to and make sense of the complex, brutal and often hidden nature of Britain’s slave history and its lasting legacies. As Levy always made clear: the history of her heritage was also a British story.

Small Island is Levy’s hugely significant contribution to the fictional retelling and exploration of West Indians’ migration to Britain in the Windrush era. Levy’s compelling neo-slave novel, The Long Song, is a historiographic metafiction, a playfully self-conscious probing of the nature of narrative and the telling of history, this time from a slave perspective in an attempt to imaginatively reenter the harsh world of plantation society and give voice, agency and humanity to the enslaved.

Levy’s earliest novels, Every Light in the House Burning (1994), set in 1960s London; Never far from Nowhere (1996), set on a North London council estate in the 1970s; and Fruit of the Lemon (1999), set in the Thatcherite Britain of the 1980s (as well as Jamaica), document domestic experiences of black British life and the particular manifestations of racism – National Front attacks, skinhead violence – prominent in British society during these periods. Later short texts, such as the short story Uriah’s War (2014), return to an earlier period and remind us that Britain and the Caribbean have long been closely connected and that West Indians – as British colonial subjects – also fought valiantly for “King and Country” in both world wars.

Levy seems to have been driven by a strong ethical imperative to tell these stories of West Indian arrival in Britain, of later generations “growing up black under the Union Jack”, to address the widespread British amnesia about its colonial history and the relative silence about Caribbean slavery in so many British institutions, including the school system.

The Small Island of Levy’s title is, of course, both Jamaica and Britain, two islands intimately and often violently yoked together by more than 300 years of shared history and culture. While Levy’s novels are set during different periods, they are all part of a longstanding, shared British-Caribbean history.

Thus, Small Island shows how the experience of the Windrush generation was marked by many of the same attitudes, inequalities and tensions found in the earlier period of plantation slavery in Jamaica, as explored in The Long Song. Levy’s 2014 essay Back to My Own Country, meanwhile, is a moving and powerful account of family, racism and her turn to writing. All are part of the largely forgotten history of Britain’s deep relationship with the Caribbean – a history which Levy’s texts show us is not just “out there” but “here (in Britain) too”.

Ultimately, what links all Levy’s texts is their deep humanity. Fittingly, Levy herself said that: “None of my books is just about race … They’re about people and history.” She described Miss July, the protagonist and chief narrator of The Long Song as “human, very smart, feisty”. There could be no better way of describing Levy as a writer.![]()

Sarah Lawson Welsh, Reader & Associate Professor in English & Postcolonial Literatures, York St John University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.