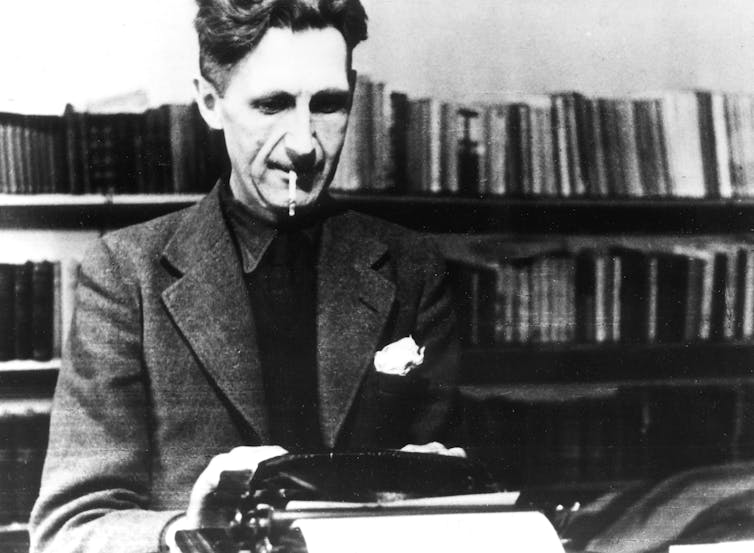

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Mark Satta, Wayne State University

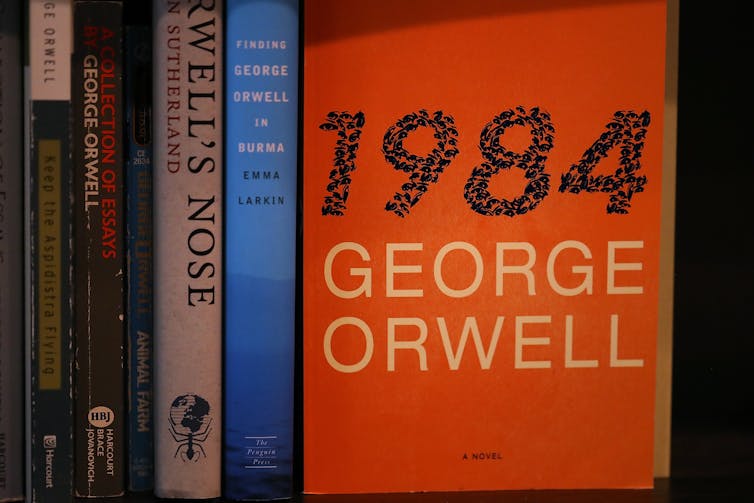

Seventy-five years ago, in August 1946, George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” was published in the United States. It was a huge success, with over a half-million copies sold in its first year. “Animal Farm” was followed three years later by an even bigger success: Orwell’s dystopian novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

In the years since, Orwell’s writing has left an indelible mark on American thought and culture. Sales of “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four” jumped in 2013 after the whistleblower Edward Snowden leaked confidential National Security Agency documents. And “Nineteen Eighty-Four” rose to the top of Amazon’s best-sellers list after Donald Trump’s Presidential Inauguration in 2017.

As a philosophy professor, I’m interested in the continuing relevance of Orwell’s ideas, including those on totalitarianism and socialism.

Early career

George Orwell was the pen name of Eric Blair. Born in 1903 in colonial India, Blair later moved to England, where he attended elite schools on scholarships. After finishing school, he joined the British civil service, working in Burma, now Myanmar. At age 24, Orwell returned to England to become a writer.

During the 1930s, Orwell had modest success as an essayist, journalist and novelist. He also served as a volunteer soldier with a left-wing militia group that fought on behalf of the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. During the conflict, Orwell experienced how propaganda could shape political narratives through observing inaccurate reporting of events he experienced firsthand.

Orwell later summarized the purpose of his writing from roughly the Spanish Civil War onward: “Every line of serious work I have written since 1936 has been, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism.”

Orwell did not specify in that passage what he meant by either totalitarianism or democratic socialism, but some of his other works clarify how he understood those terms.

What is totalitarianism?

For Orwell, totalitarianism was a political order focused on power and control. The totalitarian attitude is exemplified by the antagonist, O’Brien, in “Nineteen Eighty-Four.” The fictional O’Brien is a powerful government official who uses torture and manipulation to gain power over the thoughts and actions of the protagonist, Winston Smith. Significantly, O’Brien treats his desire for power as an end in itself. O’Brien represents power for power’s sake.

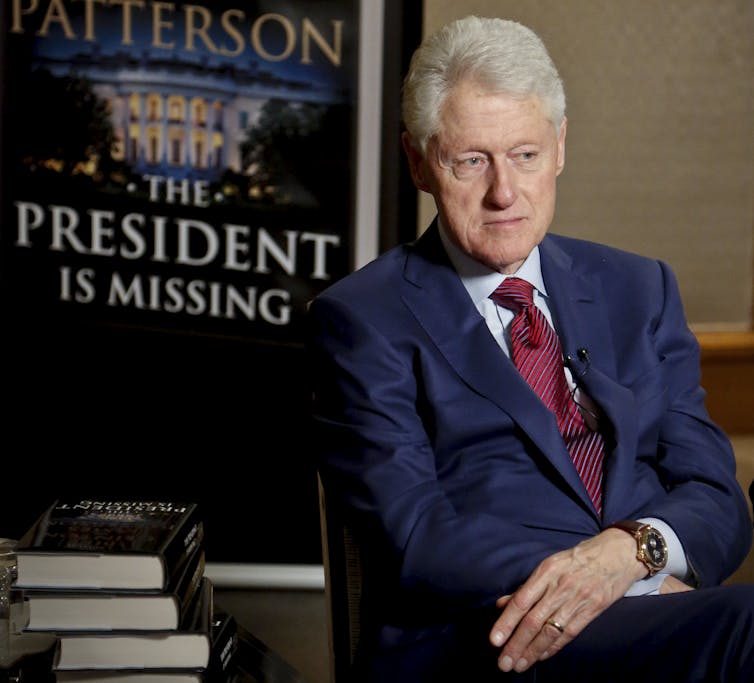

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Much of Orwell’s keenest insights concern what totalitarianism is incompatible with. In his 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell writes of “The totalitarian idea that there is no such thing as law, there is only power … .” In other words, laws can limit a ruler’s power. Totalitarianism seeks to obliterate the limits of law through the uninhibited exercise of power.

Similarly, in his 1942 essay “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” Orwell argues that totalitarianism must deny that there are neutral facts and objective truth. Orwell identifies liberty and truth as “safeguards” against totalitarianism. The exercise of liberty and the recognition of truth are actions incompatible with the total centralized control that totalitarianism requires.

Orwell understood that totalitarianism could be found on the political right and left. For Orwell, both Nazism and Communism were totalitarian.

Orwell’s work, in my view, challenges us to resist permitting leaders to engage in totalitarian behavior, regardless of political affiliation. It also reminds us that some of our best tools for resisting totalitarianism are to tell truths and to preserve liberty.

What is democratic socialism?

In his 1937 book “The Road to Wigan Pier,” Orwell writes that socialism means “justice and liberty.” The justice he refers to goes beyond mere economic justice. It also includes social and political justice.

Orwell elaborates on what he means by socialism in “The Lion and the Unicorn.” According to him, socialism requires “approximate equality of incomes (it need be no more than approximate), political democracy, and abolition of all hereditary privileges, especially in education.”

In fleshing out what he means by “approximate equality of incomes,” Orwell later says in the same essay that income equality shouldn’t be greater than a ratio of about 10 to 1. In its modern-day interpretation, this suggests Orwell could find it ethical for a CEO to make 10 times more than their employees, but not to make 300 times more, as the average CEO in the United States does today.

But in describing socialism, Orwell discusses more than economic inequality. Orwell’s writings indicate that his preferred conception of socialism also requires “political democracy.” As scholar David Dwan has noted, Orwell distinguished “two concepts of democracy.” The first concept refers to political power resting with the common people. The second is about having classical liberal freedoms, like freedom of thought. Both notions of democracy seem relevant to what Orwell means by democratic socialism. For Orwell, democratic socialism is a political order that provides social and economic equality while also preserving robust personal freedom.

I believe Orwell’s description of democratic socialism and his recognition that there are various forms socialism can take remain important today given that American political dialogue about socialism often overlooks much of the nuance Orwell brings to the subject. For example, Americans often confuse socialism with communism. Orwell helps clarify the difference between these terms.

With high levels of economic inequality, political assaults on truth and renewed concerns about totalitarianism, Orwell’s ideas remain as relevant now as they were 75 years ago.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]![]()

Mark Satta, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.