The link below is to an article on the poet William McGonagall.

For more visit:

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/disaster-poet

The link below is to an article on the poet William McGonagall.

For more visit:

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/disaster-poet

Camilla Nelson, University of Notre Dame Australia

The Australian poet Gwen Harwood used to submit poems to literary journals under both her own name and a male pseudonym, Walter Lehmann. Furious that the latter poems were more favourably received, in 1961, she sent two new sonnets to The Bulletin, penned by Lehmann, containing coded messages of abuse.

Her elaborate literary hoax became front-page news. But Donald Horne, the magazine’s editor, poured scorn on the female poet. “A genuine literary hoax would have some point to it,” he said.

In 2020, just in case this “point” is still not sufficiently clear, the Women’s Prize for Fiction has just marked its 25th anniversary by publishing 25 literary works by female authors with their real names on the cover for the first time.

Some of the books, like Middlemarch, written by Mary Ann Evans under the pen name George Eliot, are well-known, ranking among the greatest novels in English. Others have been dragged off dusty book shelves and placed in the spotlight once again.

Mary Bright, writing as George Egerton, openly talks about women’s sexuality in Keynotes, published in 1893. Ann Petry, best known as the author of The Street, the first book by an African American woman to sell more than one million copies, appears as the author of Marie of the Cabin Club, her first published short story penned under the pseudonym Arnold Petri in 1939.

Also included is Violet Paget, whose ghost story A Phantom Lover, was published under her pen name Vernon Lee. And Amantine Aurore Dupin, whose Indiana is better known for being written under the pseudonym George Sand.

For these authors, using a pseudonym was not just about slipping their work past male publishers who did not think publishing was a place for a woman. It was also about more diffuse forms of gender prejudice.

Women writers – witheringly dubbed “lady novelists” in the 19th century – also worried that their work would be marginalised as “women’s writing”; as domestic, interior, “feminine” and personal, as opposed to “masculine” themes such as history, society and politics that are, according to social norms, deemed to be more serious and culturally significant.

As George Lewes, Mary Ann Evans’ friend and life partner, put it, “the object of anonymity was to get the book judged on its own merits, and not prejudged as the work of a woman”.

In Australia, the Harwood hoax has often been relegated to the status of a literary curiosity, or mildly amusing cultural footnote. But Harwood was far from alone in feeling a sense of frustration with the male-dominated literary world.

In choosing a male pseudonym, Harwood joined the ranks of other bold and adventurous Australian women, such as Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879–1954). Franklin’s male pseudonym has been given to Australia’s most illustrious literary award, but her work – including My Brilliant Career (1901) – has not been published under her real name. The Stella Prize, established in 2013, marked this omission.

Indeed, Stella explicitly asked her publisher to delete the word “Miss” and use the name “Miles” in the hope that her work would be better received as the work of a man. “I do not wish it to be known that I’m a young girl but desire to pose as a bald-headed seer of the sterner sex,” she said.

So too, Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson (1870–1946), also known as Mrs Robertson, is only recognisable to Australian readers under the pen name Henry Handel Richardson.

Ethel used the male pseudonym to publish her literary works – including the classic women’s coming of age story, The Getting of Wisdom (1910) – because she wanted to be taken seriously as a writer.

Ethel’s gender identity was kept a secret for many years. As late as 1940 she wrote that she had chosen a man’s name because,

There had been much talk in the press of that day about the ease with which a woman’s work could be distinguished from a man’s; and I wanted to try out the truth of the assertion.

The sexually ambiguous pen name M. Barnard Eldershaw was also used by 20th century Australian writers Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw who, working in the 1920s to 1950s, penned five novels together, including Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, as well as short stories, critical essays and a radio play.

There were, of course, Australian women in the late 19th century who published under their own names, and paid the penalty.

They included Rosa Praed, Ada Cambridge, and Tasma, the pen name of Jessie Couvreur. Many were denigrated as “lady novelists” whose “romances” were witheringly labelled derivative, commercial or frivolous. And it’s likely their names are no longer recognised, except by experts.

Rosa and Ada, Stella and Ethel, for some reason, do not sound as weighty or serious as Henry and Miles, or George and Vernon. But this will not change until Australian publishers take note. It’s time to republish these Australian women under their own names.![]()

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stephanie Trigg, University of Melbourne

In our series Art for Trying Times, authors nominate a work they turn to for solace or perspective during this pandemic.

The Greeks are at the gates, and the city of Troy is under siege.

Every day, the Trojans ride out to do battle with Agamemnon, Odysseus, Ajax and the aggrieved husband Menelaus, whose wife Helen has been abducted by the Trojan prince Paris. But despite this crisis, the Trojan leisured classes carry on with their lives.

Read more:

Fall of Troy: the legend and the facts

One joyful spring morning, when the sun is shining and the meadows are filled with flowers, a beautiful young widow, Criseyde, sits in her palace, in a paved parlour with two other ladies, while a young maiden reads to them the story of another siege, that of the Greek city of Thebes.

This pleasant scene is interrupted by Criseyde’s uncle Pandarus, who is bringing the astonishing news that Paris’s younger brother Troilus has fallen in love with her.

Geoffrey Chaucer wrote his great romance Troilus and Criseyde around 1386. I teach this text every year in my honours class. It is long and difficult, and we normally spend half the semester working through the poem. Even then we don’t read it all in detail.

This year, the global pandemic brings a new context for reading this poem about a passionate but doomed love affair between two Trojans, conducted under siege conditions, in addition to all the constraints Chaucer’s very medieval lovers place around themselves.

Chaucer’s language in this text is rich and ornate, and the poem is written in a rhyming stanza whose syntax ranges from elegant to knotty. The narrative is both leisurely and intense.

It offers philosophical digressions about the nature of free will and predestination; but it is also full of intricate private meditations, and absorbing, intense conversations between the three main characters.

Nothing in the brutal rough and tumble of Shakespeare’s later play Troilus and Cressida can prepare you for the lyric drama of this poem.

Criseyde’s father has abandoned Troy and gone over to the Greek camp. She has been allowed to remain in Troy, but she is very vulnerable and fearful. The love affair must remain secret to protect her honour; Troilus and Criseyde cannot marry because he is a prince and she is the daughter of a traitor; and nor can they leave Troy and abandon their city.

They are also both overcome by shyness, dread, and reluctance to speak to each other. Indeed, the lovers do not exchange a single word until the beginning of the third book, and by the beginning of the fifth and final book they have parted, never to meet again.

Every year my students bring fresh insights to this poem’s emotional and cultural drama. Although I am on long service leave this semester, I am still conducting my annual reading of the poem on Zoom with a group of friends and colleagues.

Our Middle English Reading Group is made up of staff, present and former students, and members of a thriving community of scholars and lovers of medieval and early modern culture.

This year, reading together through Zoom offers a powerful contrast with Chaucer’s scene of medieval women’s communal reading.

Read more:

Say what? How to improve virtual catch-ups, book groups and wine nights

When Pandarus enters Criseyde’s paved parlour, where the maiden is reading from the book about the siege of Thebes, she greets him warmly and brings him to sit next to her. Hoping to turn her mood to thoughts of love, he asks what they are reading: is it a book about love? Is there anything he can learn?

Criseyde teases her uncle and when they have finished laughing she tells him where they are up to. She points to “thise lettres rede,” the rubricated or decoratively coloured chapter heading that introduces the next section.

Pandarus replies that he knows all about that sorrowful story but insists they should turn their thoughts to spring, as a prelude to introducing his news about Troilus. He invites her to dance but Criseyde recoils in horror. As a widow, she says, it would be better for her to live in a cave, to pray, and read the lives of the saints.

In typical Chaucerian fashion, this passage shows a female character’s awareness of what she might do, and perhaps should do, but does not.

Read more:

Guide to the classics: Homer’s Iliad

The domestic charms of this safe interior space, Pandarus’ fearful invitation, and the pleasures of reading and talking about familiar books distract us from the dreadful history lesson in the book they are reading. For just as Thebes was destroyed under siege, so too will Troy be.

Chaucer’s readers knew this; we know it; and even Criseyde’s father, a soothsayer, knows it: he has already abandoned Troy and gone over to the Greek camp, leaving her unprotected except for her uncle who is about to embroil her in the complexities of Trojan court politics.

We know that this love story will turn out badly. In the very first stanza, Chaucer has told us the ending of the story: that Troilus will win Criseyde, but that she will forsake him.

Knowing the ending doesn’t affect our pleasure in this text. And so we read on, absorbed by Chaucer’s capacity to conjure the lives of others as they balance distress with hope, and external disaster with private joy.

Like the Trojans, we may not be able to learn from the past so as to avoid disaster. But Chaucer is forgiving, and offers us the seductive pleasures of reading and rereading, and the comfort of repetition.

Read more:

Missing your friends? Rereading Harry Potter might be the next best thing

![]()

Stephanie Trigg, Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of English Literature, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article reporting on the winner of the 2020 ALS Gold Medal, Charmaine Papertalk Green, for ‘Nganajungu Yagu.’

For more visit:https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/06/30/152712/papertalk-green-wins-2020-als-gold-medal/

Aretha Phiri, Rhodes University and Uhuru Portia Phalafala, Stellenbosch University

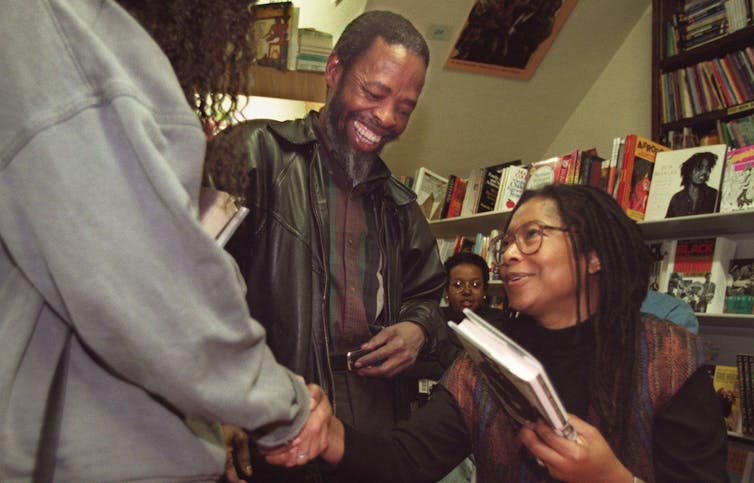

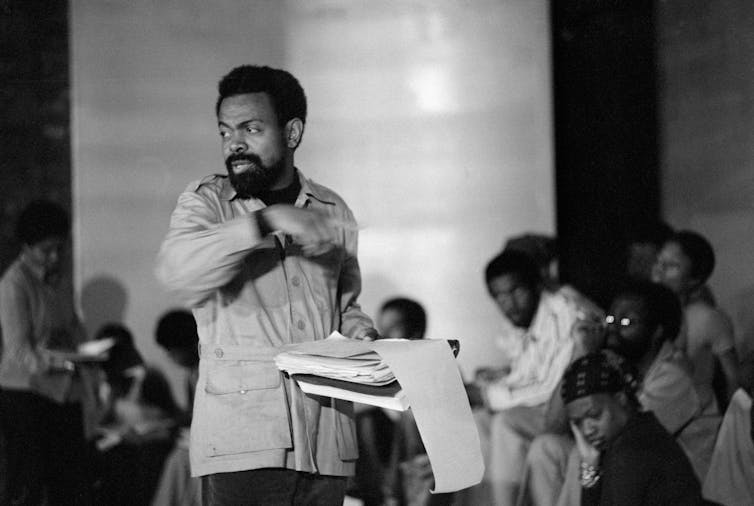

Keorapetse Kgositsile, the South African-born poet who passed away in 2018, lived in exile in the US from 1962 to 1975 and was at the centre of the country’s 1960s and ’70s Black Arts Movement. Informed by his South African and Tswana background, the poet makes a case for multiple inflections of voices, geographies, and histories in the making of transnational black modernity.

Analysing his work offers ways in which African poetry can disrupt dominant thinking on Black Atlantic studies, particularly Paul Gilroy’s

1993 text The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. The Atlantic world referred to by Gilroy tells the histories of Europe, Africa and the Americas, two hemispheres joined by the Atlantic ocean and exchanging influence. Kgositsile’s poetry can be read as challenging the direction of influence from north to south.

Uhuru Phalafala considers the rich oral traditions passed on from Kgositsile’s grandmother and mother as a key system of knowledge that informed and shaped his black radical imagination. Aretha Phiri interviewed her.

Aretha Phiri: Your colloquium paper situates the celebrated poet-in-exile at the centre of and as uniquely influential to the Black Arts Movement?

Uhuru Phalafala: It was a time when African Americans were seeking to define their identities, with Africa as key metaphor. Kgositsile happened to not only come from that continent, but also used his mother tongue, Setswana, spiritual practices, and music from southern Africa in his work. By interweaving Tswana vernacular with the black diaspora parlance, he affirmed African America’s legitimate affiliation to the continent, as seen in the example of his influence on “the grandfather of rap music”, The Last Poets.

He also came from a mass liberation movement that was experienced in politics of armed confrontation, generated solidarities with other liberation organisations, and adept in decolonial politics. His work became a resource for his contemporaries. Today, when we look at, for example, Kendrick Lamar’s influential album, To Pimp A Butterfly, and the number of references to South Africa in it, we must understand it as grounding itself in the foundation that people such as Kgositsile laid in the sixties and seventies. South Africa will always have an enduring place in the African American imagination.

This is diaspora consciousness. He also admired Nina Simone’s sound, which he called “future memory” to signal that it is not new or emergent, but reminiscent of the protest tradition of South Africa.

Aretha Phiri: In focusing on the oral traditions inherited from his female lineage, you make a case for the specific use in his poetry of a “matriarchal archive”?

Uhuru Phalafala: The colonised come from different conceptions of time (temporalities). Colonial temporality is not only racialised but also gendered. The arrogant coloniser inaugurated the beginning of history in his assumption that we did not have a history before he arrived. “History” began with the arrival of the coloniser, and marched forward in a linear fashion. With time, black men accessed modernity’s time – through missionary education and working in the mines – at a different period than women.

We now know that when anti-colonial wars were fought they were primarily and solely about the emergence of the black race from subjugation. When women and queer people attempted to bring the particularities of their oppression to the agenda they were told to wait. When independence was achieved those doubly and triply marginalised did not attain their independence at the same time with their countries because they continued to fight against black patriarchy.

If we backtrack we can then make certain observations. A type of double location of time was constructed when the colonisers’ history was instituted: theirs and ours. Because of lack of contact with missionary education and industrialisation, loosely speaking – of course there were women who accessed modernity – women occupied a different temporality. One of continuity from precolonial to colonial time, with its attendant way of life, philosophies, worldview, oratory practices, etcetera.

Aretha Phiri: In describing this archive, how do you guard against potential accusations of advancing a gendered essentialist claim?

Uhuru Phalafala I do not wish to rehash gendered essentialist claims. This is just historical process. My grandmother never set foot in a classroom but has a world of knowledge, so to say. Men who were later ferried to missionary schools, or those who went to work in the mines en masse, existed in a double location of time. The flow from precolonial to colonial time was interrupted by modernity’s time, fashioning a coexistence of the two.

Read more:

Black and queer women invite the Black Atlantic into the 21st century

These men came face to face with the colonial alienation and “first exile” from their home cultures which were denigrated by colonial assumptions of superior culture. This is how temporality is also gendered. The women who suffered the blows of this history, mostly in the rural countryside, continued to live life on their own terms, without their men. They continued to practise their indigenous ways of knowing – which are not an event but an ongoing process.

These knowledges evolved with time and did not freeze in some dark past. They progress, transform, and evolve as humans do. Today when we call for decolonisation we are actually wanting to retrieve this knowledge that was silenced and erased by the multiheaded hydra of colonialism. Where can we find it if not from those who had little contact with this hydra? In my view black women, in the context of southern Africa, are that “matriarchive”.

The book Black Radical Traditions From The South: Keorapetse Kgositsile and the Black Arts Movement by Uhuru Phalafala will be published shortly.

This article is part of a series called Decolonising the Black Atlantic in which black and queer women literary academics rethink and disrupt traditional Black Atlantic studies. The series is based on papers delivered at the Revising the Black Atlantic: African Diaspora Perspectives colloquium at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study.![]()

Aretha Phiri, Senior lecturer, Department of Literary Studies in English, Rhodes University and Uhuru Portia Phalafala, Lecturer, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

David Thomas Henry Wright, Nagoya University

Since lockdown, everyone has had to rely heavily on digital technologies: be it Zoom work meetings and lengthy email chains, gaming and streaming services for entertainment, or social media platforms to organise everything from groceries to protests. Human existence is now permeated by non-human computer language.

This includes poetry. Digital technologies can disseminate and publish contemporary poetry, and also create it.

Digital artists combine human and computer languages to create digital poetry, which can be grouped into at least five genres.

Generative poems use a program or algorithm to generate poetic text from a database of words and phrases written or gathered by the digital poet.

The poem may run for a fixed period, a fixed number of times, or indefinitely. Dial by Lai-Tze Fan and Nick Montfort, for example, is a generative poem that represents networked, distant communication. It depicts two isolated voices engaged in a dialogue over time. Time can be adjusted by clicking the clocks at the bottom of this emoji-embedded work.

The recent web-based work Say Their Names! by digital artist John Barber generates a list from more than 5,000 names of Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans who have been killed by police officers in the United States from 2015 to the present day. No judgement regarding the victims’ guilt or innocence is made. Each name is simply spoken – in a sometimes incongruously cheerful tone – by a computerised voice.

Read more:

Listen to me: machines learn to understand how we speak

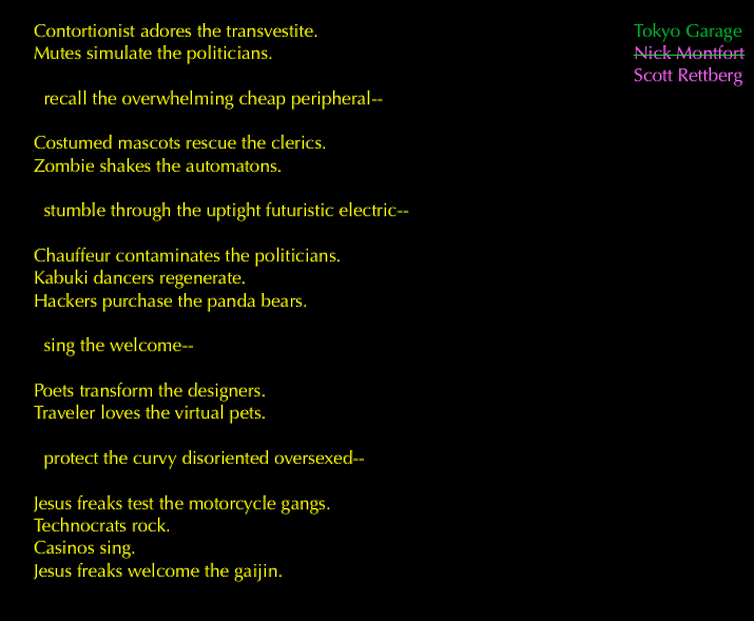

Nick Montfort’s generative poem Taroko Gorge was inspired by a visit to Taroko Gorge in Taiwan.

Montfort writes: “If others could go to a place of natural beauty and write a poem about that place, why couldn’t I write a poetry generator, instead?” Scott Rettberg then took the code from Montfort’s poem and replaced the vocabulary to produce Tokyo Garage, turning Montfort’s minimalist nature poem into a maximalist urban poem.

J.R. Carpenter undertook a similar transformation – replacing the nature vocabulary with words associated with eating.

There are now dozens of Taroko Gorge remixes. By inspecting the source of Montfort’s poem, one can carve into the code to remix one’s own version.

For centuries, poets have combined poetry and images. In the late 1700s, William Blake combined poetry with engraved artwork in his conceptual collection Songs of Innocence. Contemporary poets use digital technologies to similarly adorn poetry with imagery.

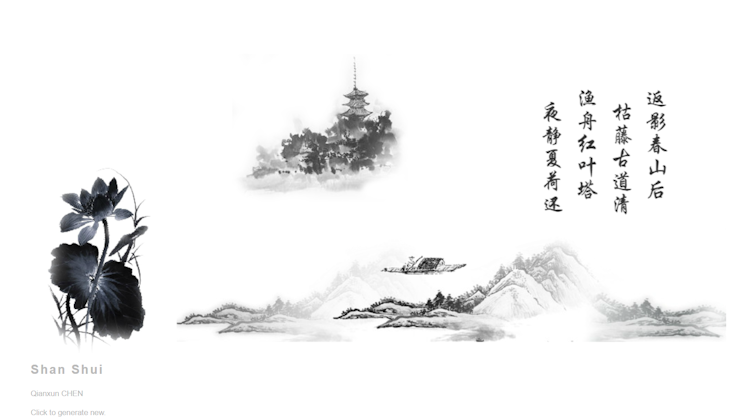

The title of Qianxun Chen’s work Shan Shui means mountain and water in Chinese, and landscape when combined as shanshui. It also refers to traditional Chinese landscape painting and a style of poetry that conveys the beauty of nature. With each click, a new Shan Shui poem is generated with a corresponding Shan Shui landscape painting.

Visuals also find their way into poetry performance. The Buoy by Meredith Morran is a poetic work of auto-fiction that uses a series of diagrams to create a new form of language to address political issues involving marginalised identities.

Morran combines abstract images, performance and PowerPoint presentation software to indirectly address a personal history of growing up queer in Texas.

Read more:

Friday essay: a real life experiment illuminates the future of books and reading

The 1960s and 70s saw the emergence of text-based computer games, such as Zork, the source code of which is archived at the MIT libraries.

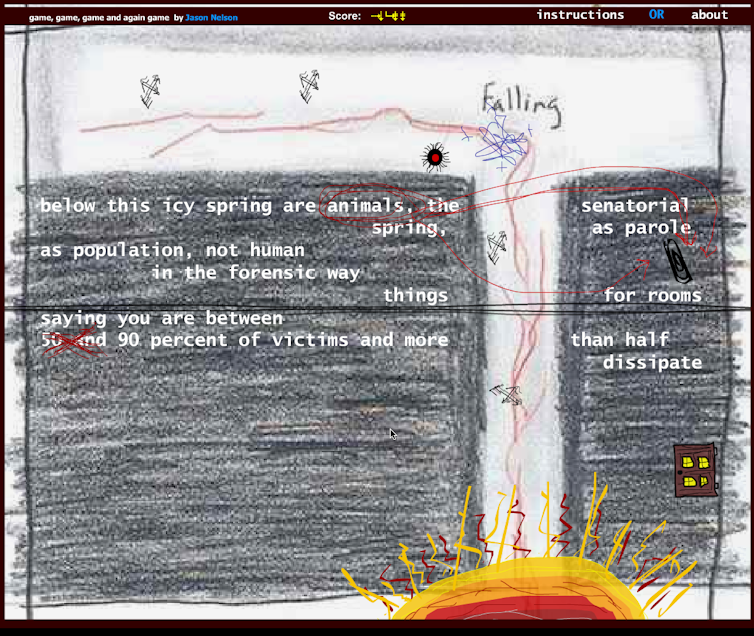

Queensland digital poet Jason Nelson has created a number of works that fuse these two modes. One is called game, game, game, and again game, which Nelson describes as “a digital poem, retro-game, an anti-design statement, and a personal exploration of the artist’s changing worldview lens”. The work disrupts commercial video game design with the player not striving for a high score – but instead moving, jumping, and falling through an excessive, disjointed, poetic atmosphere.

The emergence of virtual reality games, such as Half-Life: Alyx, has also met with poetry.

Australian digital artist Mez Breeze’s V[R]ignettes is a virtual reality microstory series. The audience can experience this work by donning a virtual reality headset or viewing it in 3D space in browser. Each V[R]ignette combines poetic text, 3D models, and atmospheric sound design. The reader (or user) can navigate by clicking on the “Select an annotation” bar at the bottom of the screen, or simply look around in 3D space and freely explore the work.

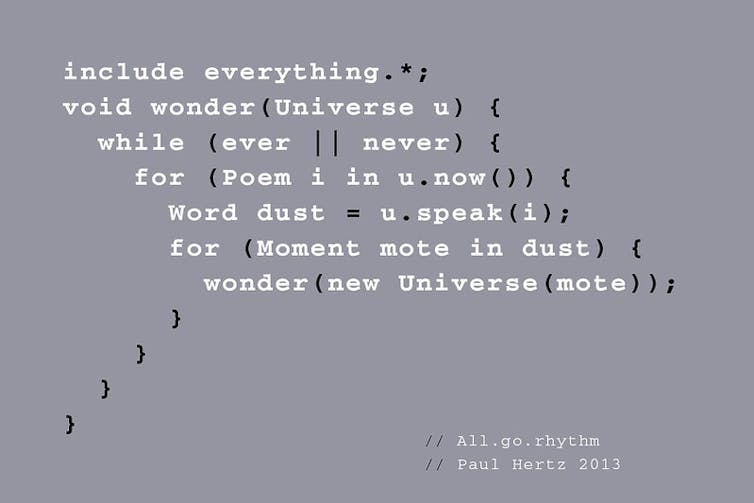

Code poetry is a genre that combines classical poetry with computer language.

Code poems, such as those compiled by Ishac Bertran in the print collection code {poems}, do not require a computer to exist. However, they do use computer languages, so to comprehend the poem one must be able to read computer code.

Like so many untranslatable Russian and Chinese poems, these works require a knowledge of the original language to be appreciated.![]()

David Thomas Henry Wright, Associate Professor, Nagoya University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that reflects on the life and work of poet Michael McClure, who died in May 4, 2020.

For more visit:

https://lithub.com/remembering-michael-mcclure-poet-teacher-friend/

Stephen Rigby, University of Manchester

The sharp fall in population caused by the waves of plague which followed the arrival of the Black Death in 1348 led to one of the most dramatic periods of economic and social change in English history. By 1377, the population was around only a half of its pre-plague level but for those who survived there were new opportunities.

With a great deal of land now available, peasants could obtain larger holdings and rent them on more favourable terms. Likewise, those who worked for wages could take advantage of the labour shortage to obtain higher wages enjoy more varied diets – with more meat and dairy – and buy a wider range of manufactured goods.

The second half of the 14th century was thus a period of rising living standards, social mobility and increasing class conflict as the lower orders now sought to obtain improved terms from their landlords and employers.

The dramatic social changes of these years drew several responses from contemporary poets. In the medieval period, imaginative literature was often seen as having an ethical function by teaching virtue, which was defined as fulfilling the expected tasks of their social order. Modern literary critics often see imaginative literature challenging dominant ideologies or providing a sanctioned space for the expression of social dissidence. By contrast, the work of poets in the post-plague era often sought to buttress the social hierarchy against the threats with which it was now confronted.

Such sentiments are to be found in William Langland’s allegorical poem, Piers Plowman (B-version written c. 1380). Here, the poet expresses his sympathy for those who were genuinely poor or hard-working but echoes post-plague labour legislation and attacked those who, he believed, preferred to beg rather than work.

There had been frequent complaints in parliament about labourers who preferred handouts to work or who took advantage of the labour shortage to demand higher wages. In response, a series of laws were introduced to reduce labour mobility and freeze wages at their pre-plague levels. Langland also calls upon the knightly class to defend the community from those “wasters” who refused to work and criticised the labourers who impatiently demanded higher wages and refused to obey the new legislation.

Contemporary moralists complained about those who rose above their allotted station in life and so in 1363 a law was passed that specified the food and dress that were appropriate for each social class. In line with such attitudes, Langland railed against the presumption of labourers who disdained day-old vegetables, bacon and cheap ale and instead demanded fresh meat, fish and fine ale.

Similar views are expressed in John Gower’s poem Vox Clamantis (the Voice of One Crying in the Wilderness) where the peasants are attacked for being idle and utterly wicked. The common people had fallen into an evil disposition in which they ignored the labour laws and were only willing to work if they received the highest pay.

When the lower orders refused to know their place, as in the Great Revolt of 1381 (also known as the Peasants’ Revolt), they were denounced by contemporary chroniclers as wicked, treacherous, and diabolical. In line with such criticism, Gower’s poem includes an allegorical account of the rising that portrays the rebels as farmyard animals rising up against their masters. They subsequently turn into monsters that attack humanity and becoming followers of Satan in their attachment to wrongdoing and slaughter.

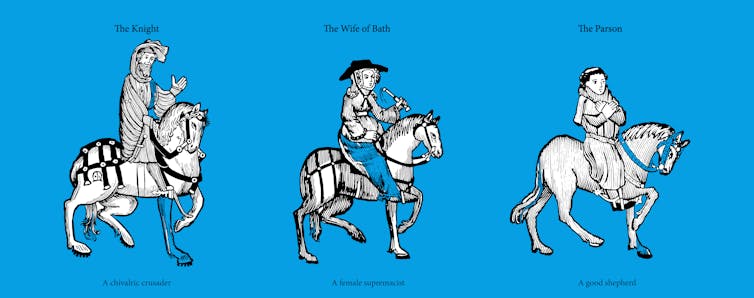

However, if Langland and Gower were openly hostile to the aspirations of the peasants and the labourers, Geoffrey Chaucer has proved more difficult to read. For many critics, Chaucer is a writer who prefers to present his readers with questions rather than providing them with stock answers. To them, his use of multiple voices and shifting perspectives pose a challenge to the accepted contemporary beliefs and exposes the kind of ideology found in the works of a Gower as partial and inadequate.

Yet for other critics, Chaucer is much more conservative or even, as the medieval scholar Alcuin Blamires puts it, reactionary in his outlook. After all, among the pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales, those who are presented as admirable are the ones who dutifully perform the traditional functions of their social estate. For example, the Parson is a good shepherd to his flock, the Knight is a chivalrous crusader, and the Plowman works hard and faithfully pays his tithes. It is those who fail in their duties or seek to rise above their station whom Chaucer satirises – as when the Monk prefers hunting to a life of study and prayer or when the Wife of Bath seeks female supremacy in marriage.

Certainly, the Parson offers us a socially conservative message when, at the end of the Canterbury Tales, he preaches that as part of the divinely arranged cosmic order, God has ordained that some people should be of higher social rank and others should be lower. People should, therefore, render honour and obedience not only to God but also to their spiritual fathers and their secular superiors. Nobody should lament their misfortunes or envy the prosperity of others but rather should endure adversity in patience in the hope of obtaining joy and ease in the next life.

Given that medieval literary theory regards the ending of a text as being particularly important in conveying its meaning, we may perhaps regard Chaucer’s views as being in line with his Parson. If so, then Chaucer’s response to the social change of his day may have been rather closer to the views of Gower and Langland than many of his modern readers would like to admit.

Read and listen more from the Recovery series here.![]()

Stephen Rigby, Emeritus Professor of Medieval Social and Economic History, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that reports on the winner of the 2020 Moth Poetry Prize.

For more visit:

https://www.booksandpublishing.com.au/articles/2020/05/01/149857/obrien-wins-e10000-moth-poetry-prize/

Kenrick Mills/Unsplash

Christopher Wallace-Crabbe, University of Melbourne

Why do we have the arts? Why do they seem to matter so much? It is all very well muttering something vague about eternal truths and spiritual values. Or even gesturing toward Bach and Leonardo da Vinci, along with our own Patrick White.

But what can the poets make of, and for, our busy, present lives? What do they have to say during grave crises?

Well, they can speak eloquently to their readers for life, in writing from the very base of their own experiences. Every generation has laid claim, afresh, to its vital modernity. In the 17th century, Andrew Marvell did so with witty lyrical elegance in his verse To a Coy Mistress. Three centuries later, the French poet René Char thought of us as weaving tapestries against the threat of extinction. Accordingly, he wrote:

The poet is not angry at the hideous extinction of death, but confident of his own particular touch, he transforms everything into long wools.

In short, the poet will, at best, weave lasting, memorable, salvific tapestries out of words. The poems in question will come out live, if the poet is lucky, and possibly as disparate as the sleepy, furred animals caged in Melbourne Zoo.

Read more:

A beginner’s guide to reading and enjoying poetry

What is truly touching or intimate need not be tapped by elegies, for all that they can fill a mortal need. Yet the great modern poet W. H. Auden wrote in memory of poet, writer and broadcaster John Betjeman:

There is one, only one object in his world which is at once sacred and hated, but it is far too formidable to be satirizable: namely Death.

As William Wordsworth and Judith Wright both well knew, in their separate generations – and quite polar cultures – the best poetry grasps moments of our ordinary lives, and renders them memorable.

Poetry can give us back our dailiness in musical technicolour: in a thousand yarns or snapshots. Poems sing to us that life really matters, now. That can emerge as songs or satires, laments, landscapes or even somebody’s portrait done in imaginative words.

Yes, verse at its finest is living truth “done” in verbal art. The great Russian playwright Anton Chekhov once insisted “nothing ever happens later”, and the point of poetry in our own time – as always, at its best – is surely to shine the light of language on what is happening now. The devil is in the detail, yes. But so is the redemptive beauty, along with “the prophetess Deborah under her palm-tree” in the words of the Australian poet, Peter Steele.

Poetry sees the palm tree, and the prophetess herself, vividly, even in the middle of a widespread epidemic.

Read more:

Ode to the poem: why memorising poetry still matters for human connection

Modern poetry is an art made out of living language. In these times, at least, it tends to be concise, barely spilling over the end of the page: too tidy for that, unlike the vast memorised narratives of the Israelites, the Greeks or even the Icelanders. But what it shares with the ancient, oral cultures is its connection with wisdom, crystallising nodes of value, fables of the tribe, moments or decades that made us all.

In the brief age of a national pandemic, poetry’s role and its duties may come to seem all the more important: all the more civil and politically sane. The poem – even in the case when it is quite a short lyric, even if comic – carries the message of moral responsibility in its saddle bag. Perhaps all poets do, even when they are also charming the pants off their willing readers.

Christopher Wallace-Crabbe is judge of the ACU Prize for Poetry. Entries close July 6.![]()

Christopher Wallace-Crabbe, Emeritus Professor in the Australian Centre, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.