Photo by Bruce Milton Miller/Fairfax Media via Getty Images.

Kingsley Ugwuanyi, Northumbria University, Newcastle

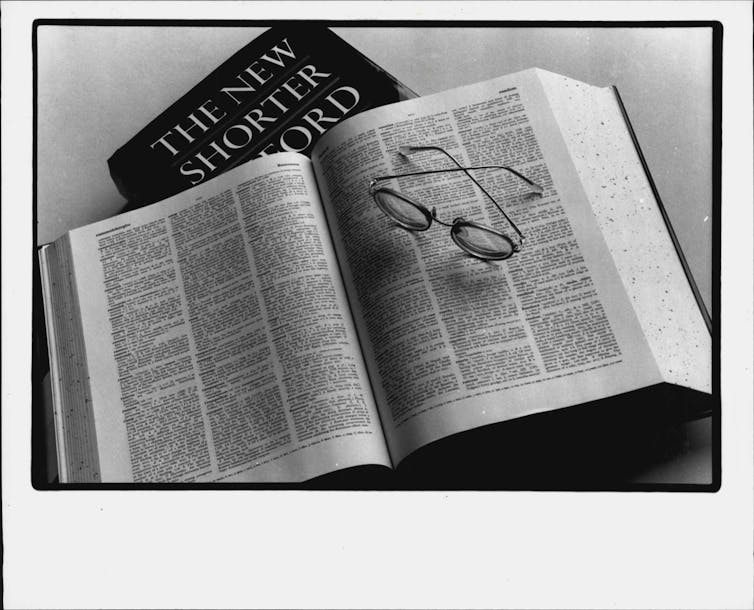

Nigeria was recently in the spotlight when the Oxford English Dictionary announced that its January 2020 update included 29 Nigerian English words.

The reception, in both the traditional and new media, was nothing short of sensational. Most Nigerians expressed a great sense of pride in the fact that the unique ways in which they use English were being acknowledged internationally.

The Oxford English Dictionary said in the release note:

By taking ownership of English and using it as their own medium of expression, Nigerians have made, and are continuing to make, a unique and distinctive contribution to English as a global language.

Interestingly, the idea of Nigerians owning English is the fulcrum of my doctoral research. In it, I found that increasingly Nigerians are demonstrating a strong sense of ownership of the English language, and in particular their use of it.

The inclusion of Nigerian English words in the Oxford English Dictionary is, in a sense, a recognition of the tremendous efforts by scholars of Nigerian English many of whom have produced discipline-shaping research. This has included four published dictionaries of Nigerian English.

These developments indicate that Nigerian English has indeed come of age. They also validate the concentric circle model developed by Professor Braj Kachru, the father of world Englishes research. This avers that the ‘outer-circle’ varieties of English (where Nigerian English belongs) is ‘norm-developing’. In other words, that Nigerian English is adding to the norms of English.

I think the English, indeed the English-speaking world, should be thankful to Nigeria for this historic gift.

So how were the words chosen?

As the Nigerian consultant to the project which saw the inclusion of the words, I have insights into the process the team underwent in adding them. These include the rationale for adding them, and the enormous significance the inclusion holds for the English language.

How, and why, new words are added

The Oxford English Dictionary has a wide variety of resources to track the emergence of new words and new senses of already existing words.

The Oxford English Corpus is one. This is an electronic database of different types of written and spoken texts specifically designed for linguistic research. In the case of Nigerian English and other World English varieties, for instance, suggestions of new words and senses come from the corpus, reading books and magazines written in the English varieties in question as well as looking at previous studies, and the review of existing dictionaries, if any.

Once there is a list of candidates, a team of expert editors at the Oxford English Dictionary looks closely at the databases to ensure that there are several independent instances of the words being used. And how they are being used.

Other factors that are considered include the time period over which words have been used, as well as their frequency and distribution. But there’s no exact time-span and frequency threshold. Some words – such as Brexit – are relatively young but were included quickly because of the huge social impact they had in a short space of time. Others are not used frequently but are included because they are of specific cultural, historical, or linguistic significance to the community of their users. An example is ‘Kannywood’, the word describing the Nigerian Hausa-language film industry, based in the city of Kano.

It’s clear therefore that the editors don’t simply select the words or senses that appeal to them. Instead, they are guided by use, which links in with the prevailing thought in lexicography and linguistics more generally: that the remit of dictionaries and linguistic research is not to prescribe how languages should be used but to describe how languages are being used.

Words are added because the Oxford English Dictionary recognises that English is a universal language. It believes that including words from varieties of English all over the world enables it to tell a more complete story of the language.

These varieties also reflect the unique culture, history, and identity of the various communities that use English across the world. Nigerian English is a good example. Like other English varieties, it is a living ‘being’ with its own unique vocabulary, encompassing all sorts of lexical innovations. These include borrowings from local languages, new abbreviations, blends and compounds.

Failure to capture such words would deny English an opportunity to grow. It would also deny the flavour of what the speakers of these varieties contribute to the development of English.

What does it mean for English?

One of the reasons previous world languages such as Egyptian and Ancient Greek ceased to exert dominance internationally was their inability to keep pace with developments around the world.

Perhaps this is one factor that clearly distinguishes English. It has demonstrated a capacity for growth by keeping its borders open, helping it to develop from a West Germanic dialect spoken in a small island into a world language. English is now spoken by about 1.75 billion people – a quarter of the

world’s population. This includes first and second language speakers.

One way English grows is by admitting new words and senses not just from other English varieties but from virtually all languages of the world. For instance, English has had the word ‘postpone’ since the late 15th century, but it was through India that its opposite ‘prepone’ entered English in current use during the 20th century.

Similarly, Nigerian English is reintroducing the verb meaning of ‘barb’, which existed in 16th century British English.

This is how English maintains its dominance. In addition, the Internet has given today’s Oxford English Dictionary editors wider access to non-traditional sources of linguistic evidence. This has enabled them to widen and improve the dictionary’s coverage of world varieties of English, affirming Oxford English Dictionary’s claim as “the definitive record of the English language”.![]()

Kingsley Ugwuanyi, Lecturer/Doctoral Researcher, Northumbria University, Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.