Giovanni Boccaccio, Petrarch, Cino da Pistoia, Guittone d’Arezzo and Guido Cavalcanti are depicted in the oil painting.

Wikimedia/MIA

Maria Clotilde Camboni, University of Oxford

Imagine a world where we knew the name of Homer, but the poetry of The Odyssey was lost to us. That was the world of the early Italian Renaissance during the second half of the 15th century.

Many people knew the names of some early poets of Italian literature – those who were active during the 13th century. But they could not read their poems because they had not been printed and were not circulating in manuscripts.

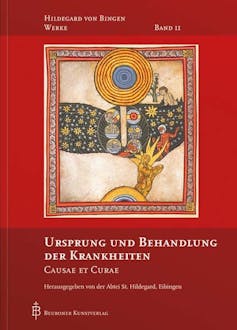

Then, in around 1477 the de facto sovereign of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici – “the Magnificent” – commissioned the creation of an anthology of rare early Italian poetry to be sent to Federico d’Aragona, son of the king of Naples.

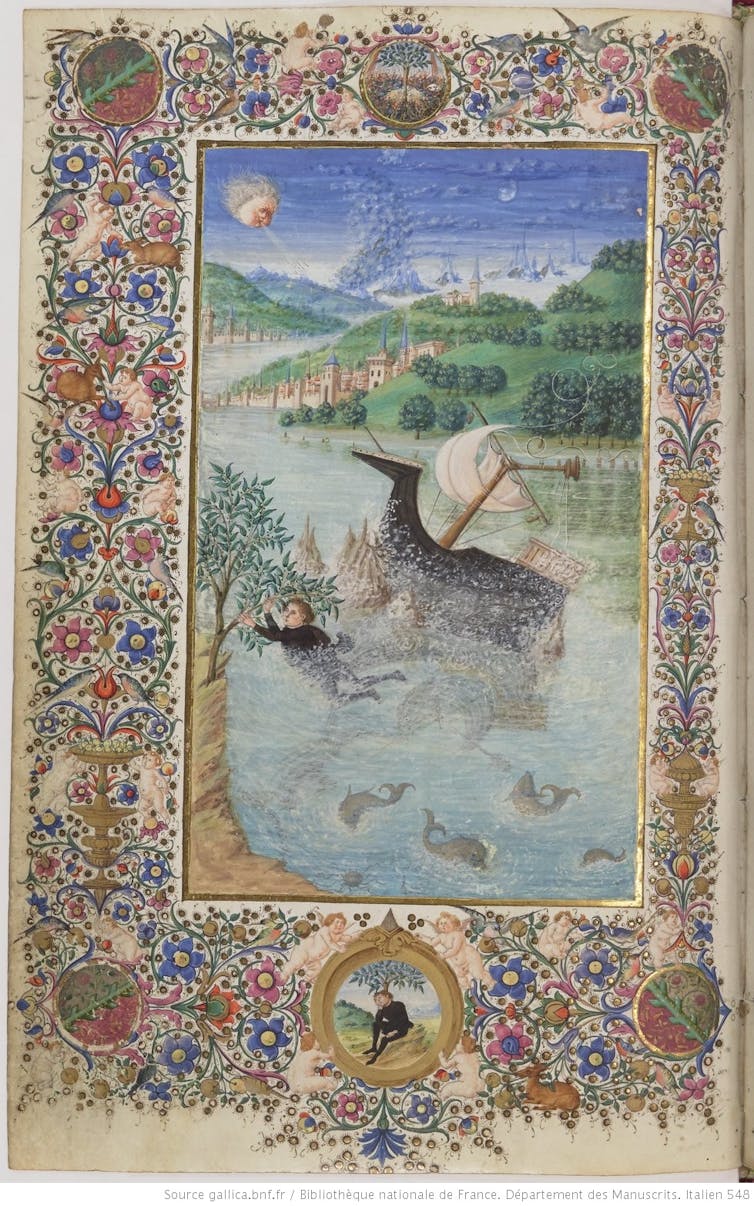

The luxurious manuscript became one of Federico’s most prized possessions. It was exhibited to and coveted by patricians and intellectuals for half a century – until its disappearance in the early 16th century.

Gallica/Bibliothèque nationale de France

But it did not disappear completely. The interest aroused by this manuscript generated a paper trail of letters, partial copies and other materials which I, along with other researchers, have managed to piece together. These documents allow us to reconstruct not only the trajectory of the manuscript through different courts in Europe, but – crucially – what works it may have contained.

Who were the vernacular poets?

Vernacular literature – that is, literature written in the language normally spoken by the people – only had a marginal role during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. The “real” culture was Latin. This meant that interest in the early poets who wrote in the Italian vernacular was limited – until the flourishing of the Italian language in the age of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

One of these 13th-century poets, Cino da Pistoia, was loved and celebrated by Dante Alighieri in his treatise on the art of poetry, “De vulgari eloquentia”. Dante said of his contemporary Cino:

There are a few, I feel, who have understood the excellence of the vernacular: these include Guido, Lapo … and Cino, from Pistoia, whom I place unworthily here at the end, moved by a consideration that is far from unworthy.

Britannica.com

Guido Cavalcanti was another love poet. He and Dante were best friends and Dante regarded Cavalcanti as an authority on poetry. Cavalcanti is mentioned in Dante’s early poetry collection, the Vita nova.

The whole work is addressed to Cavalcanti and Dante even implies that he is writing in Italian because of him. But despite Dante’s popularity, even the Vita nova was hard to get hold of before 1576 when it was printed for the first time.

Guittone d’Arezzo was another highly regarded poet. He started as a love poet before becoming the most important author (before Dante) writing on moral and political themes.

The Raccolta Aragonese

The collection of Tuscan poetry sent to Federico d’Aragona by Lorenzo de’ Medici in 1477 contained Dante’s Vita nova, as well as rare poems recovered from ancient manuscripts by Cino, Guittone, Cavalcanti and many others. The collection was opened by a letter signed by Lorenzo himself.

The manuscript was later named after its owner and became the Raccolta Aragonese (“the Aragon collection”). It became one of Federico’s most prized possessions and the object of widespread interest and curiosity.

Federico took it with him when he travelled to Rome at the end of 1492 to swear allegiance to the Borgia Pope Alexander VI. During this trip, he showed it to the scholar Paolo Cortesi, who immediately wrote to Piero de’ Medici – the son of the recently deceased Lorenzo the Magnificent. In this letter, Cortesi recounts that he had been shown a manuscript with poems by early vernacular poets, chiefly Cino and Guittone. The excitement is palpable: Cortesi is able to read poems by these authors whose names he had only ever heard mentioned before.

Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Such was the interest in these lost poets that partial copies of the Raccolta started to circulate. The first one was probably made by someone in Federico’s inner circle before he became King of Naples in 1496. News about his collection of rare early Italian poems was spreading.

The widow queen and the duchess

Federico was the last sovereign of his dynasty. He lost his throne when Louis XII of France invaded Italy. When he left Naples in the summer of 1501, Federico took the books of the royal library with him. He later had to sell part of them to sustain himself and his followers during his exile in France. But the Raccolta Aragonese was not sold and after his death in 1504 it was passed on to his widow, Isabella del Balzo.

Wikimedia/KunsthistorischesMuseum

The widow queen then lent the collection to Isabella d’Este, the Duchess of Mantua, in northern Italy, in 1512. She kept it for two months and, even though in her letters she promised not to leave it in other people’s hands, it is likely that she commissioned a complete copy which led to further partial copies being made.

Even though the transmission of these copies was in manuscript form – and so not widespread – several Renaissance intellectuals managed to read these “lost” works and were influenced by them in their attempts to reconstruct the history of Italian literature.

The real game-changer came in 1527 when a printed collection of vernacular poetry finally took the works of masters like Cino, Guittone and Cavalcanti to a much wider audience. This is when they stopped being obscure and arcane authors and finally took their place in the canon of Italian literature.![]()

Maria Clotilde Camboni, , University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.