Klaus Vedfelt/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Eurie Dahn, The College of Saint Rose

Using punctuation and capitalization as a form of protest doesn’t exactly scream radicalism.

But in debates over racial justice, punctuation can carry a lot of weight.

During the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, mainstream news organizations grappled with whether to capitalize the first letter of “black” when referring to Black people. Of course, writing “Black” was already common practice in activist circles. Eventually The Associated Press, The New York Times, USA Today and many other outlets declared that they, too, would capitalize that first letter.

It turns out the push to capitalize “black” is only the most recent way Black writers and activists have pushed back against entrenched power through ostensibly bland elements of writing.

As I discuss in my recent book, “Jim Crow Networks: African American Periodical Cultures,” Black activism in the media can take a variety of forms – some more subtle than others.

Seemingly unimportant elements of writing have long been adapted as tools of Black activism. Much like the recent drive to capitalize “black,” activists have deployed punctuation to question the legitimacy of confessions, criticize justifications made for lynchings and highlight the undervaluing of Black expertise and knowledge.

The power of punctuation

Punctuation was developed in the 3rd century B.C. to visually separate sentences and improve comprehension. But punctuation can do more than clarify. It can extend, contradict and play with meaning.

Think of the difference between ending a sentence with an exclamation point and with an ellipsis, or the way emoticons made of repurposed punctuation can be used to denote sarcasm or add playfulness and emotion.

This makes it a useful tool for activists who seek to upend dominant narratives.

Quotation marks convey suspicion

A push to capitalize has actually happened before.

In the 1920s, influential Black intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois wrote to The New York Times and Encyclopedia Britannica to argue that the word “negro” ought to have its first letter capitalized.

A decade later, to counter racism in the white press, the Black press used quotation marks when reporting on the case of a young man named Robert Nixon, who was convicted of murder.

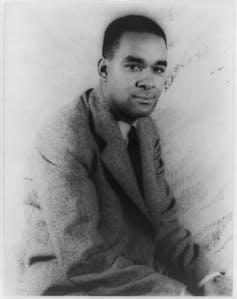

In 1938, the white-owned Chicago Tribune notoriously described Nixon – who would serve as the basis for protagonist Bigger Thomas in Richard Wright’s 1940 novel “Native Son” – as an “animal” whose “physical characteristics suggest an earlier link in the species.”

Library of Congress

However, the city’s influential Black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, covered the case differently, reporting Nixon’s claim that his confession was the result of police coercion. In a 1938 article, the Defender included a subheading that declared, “Nixon Also Refutes ‘Confession’.”

These simple quotation marks signaled doubt over the legitimacy of this confession, while teaching newspaper readers to be suspicious of so-called legal facts.

As sociologist Mary Pattillo notes in her book “Black on the Block,” the Defender’s strategic use of quotation marks called into question official accounts of Nixon as a murderer. In doing so, the paper highlighted the unfair treatment of Black people by the media, police and court system.

The code of the question mark

Similarly, Black activists used question marks to criticize mainstream accounts of events during the Jim Crow era.

In her 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells used question marks in parentheses on four occasions to interrogate descriptions of crimes supposedly committed by Black Americans.

For example, she wrote, “So great is Southern hate and prejudice, they legally(?) hung poor little thirteen year old Mildrey Brown at Columbia, S. C., Oct. 7th, on the circumstantial evidence that she poisoned a white infant.”

She also quoted from one of her earlier newspaper editorials in which she discussed the lynchings of eight Black men by saying that, in each case, “citizens broke(?) into the penitentiary and got their man.” The question mark casts doubt on this “break-in” and suggests that the perpetrators were, in fact, aided and abetted by law enforcement in murdering these men.

These simple question marks subtly undermined a legal system that sought to cast the murders of a young girl and eight men as just responses. Wells indicted not only the legal system but also the white press, which was often an accomplice to racial violence.

[Over 106,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Afrofuturist questions

Wikimedia Commons

The writer, editor and activist Pauline E. Hopkins similarly used question marks within parentheses in her early Afrofuturist novel “Of One Blood.”

The novel – which contains depictions of a leopard attack, a lost African city and a ghost – was serialized in the pages of the Colored American Magazine from 1902 to 1903. At one point, the protagonist, a Black doctor, brings a patient back to life. Yet the responses to this miracle display ambivalence:

“The scientific journals of the next month contained wonderful and wondering (?) accounts of the now celebrated case, – re-animation after seeming death.”

Much as Wells used the question mark to dismiss the official accounts of lynchings, Hopkins deploys it to undermine the scientific establishment and cast doubt on the journals for their stunned and disbelieving responses to the medical marvel.

For Hopkins, the question mark worked to demand respect for Black expertise and knowledge.

Punctuation’s possibilities

Punctuation activism can be an important companion to on-the-ground activism. It reveals language’s capacity to transform the world. At the same time, it exposes language’s often hidden role in maintaining structures of power.

Certainly, punctuation – like language overall – is typically used in less radical ways. But these examples of early 20th century Black writers, activists and journalists point to punctuation’s possibilities in questioning entrenched power structures and laying claim to alternative futures.![]()

Eurie Dahn, Associate Professor of English, The College of Saint Rose

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.