David Thomas Henry Wright, Nagoya University

Since lockdown, everyone has had to rely heavily on digital technologies: be it Zoom work meetings and lengthy email chains, gaming and streaming services for entertainment, or social media platforms to organise everything from groceries to protests. Human existence is now permeated by non-human computer language.

This includes poetry. Digital technologies can disseminate and publish contemporary poetry, and also create it.

Digital artists combine human and computer languages to create digital poetry, which can be grouped into at least five genres.

1. Generative poetry

Generative poems use a program or algorithm to generate poetic text from a database of words and phrases written or gathered by the digital poet.

The poem may run for a fixed period, a fixed number of times, or indefinitely. Dial by Lai-Tze Fan and Nick Montfort, for example, is a generative poem that represents networked, distant communication. It depicts two isolated voices engaged in a dialogue over time. Time can be adjusted by clicking the clocks at the bottom of this emoji-embedded work.

nickm.com

The recent web-based work Say Their Names! by digital artist John Barber generates a list from more than 5,000 names of Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans who have been killed by police officers in the United States from 2015 to the present day. No judgement regarding the victims’ guilt or innocence is made. Each name is simply spoken – in a sometimes incongruously cheerful tone – by a computerised voice.

Read more:

Listen to me: machines learn to understand how we speak

2. Remixed poetry

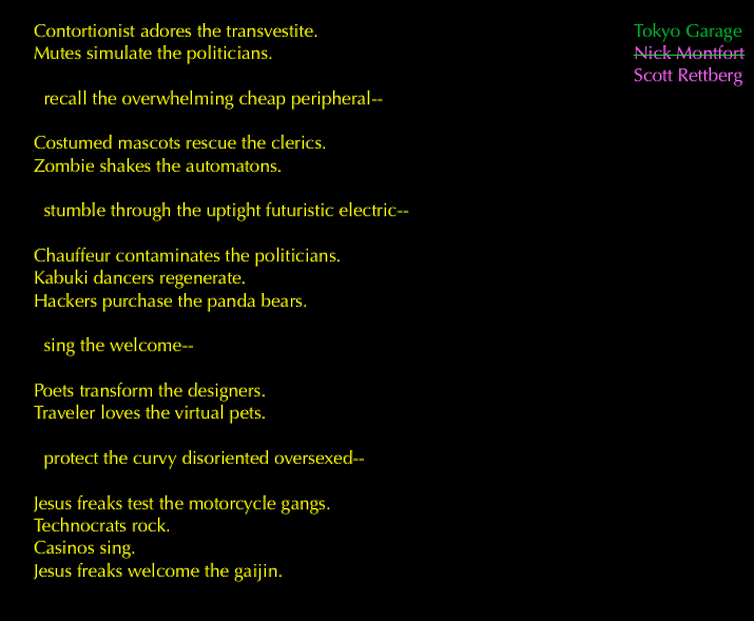

Nick Montfort’s generative poem Taroko Gorge was inspired by a visit to Taroko Gorge in Taiwan.

Montfort writes: “If others could go to a place of natural beauty and write a poem about that place, why couldn’t I write a poetry generator, instead?” Scott Rettberg then took the code from Montfort’s poem and replaced the vocabulary to produce Tokyo Garage, turning Montfort’s minimalist nature poem into a maximalist urban poem.

J.R. Carpenter undertook a similar transformation – replacing the nature vocabulary with words associated with eating.

There are now dozens of Taroko Gorge remixes. By inspecting the source of Montfort’s poem, one can carve into the code to remix one’s own version.

3. Visual verse

For centuries, poets have combined poetry and images. In the late 1700s, William Blake combined poetry with engraved artwork in his conceptual collection Songs of Innocence. Contemporary poets use digital technologies to similarly adorn poetry with imagery.

The title of Qianxun Chen’s work Shan Shui means mountain and water in Chinese, and landscape when combined as shanshui. It also refers to traditional Chinese landscape painting and a style of poetry that conveys the beauty of nature. With each click, a new Shan Shui poem is generated with a corresponding Shan Shui landscape painting.

elmcip.net

Visuals also find their way into poetry performance. The Buoy by Meredith Morran is a poetic work of auto-fiction that uses a series of diagrams to create a new form of language to address political issues involving marginalised identities.

Morran combines abstract images, performance and PowerPoint presentation software to indirectly address a personal history of growing up queer in Texas.

Read more:

Friday essay: a real life experiment illuminates the future of books and reading

4. Video game poem plays

The 1960s and 70s saw the emergence of text-based computer games, such as Zork, the source code of which is archived at the MIT libraries.

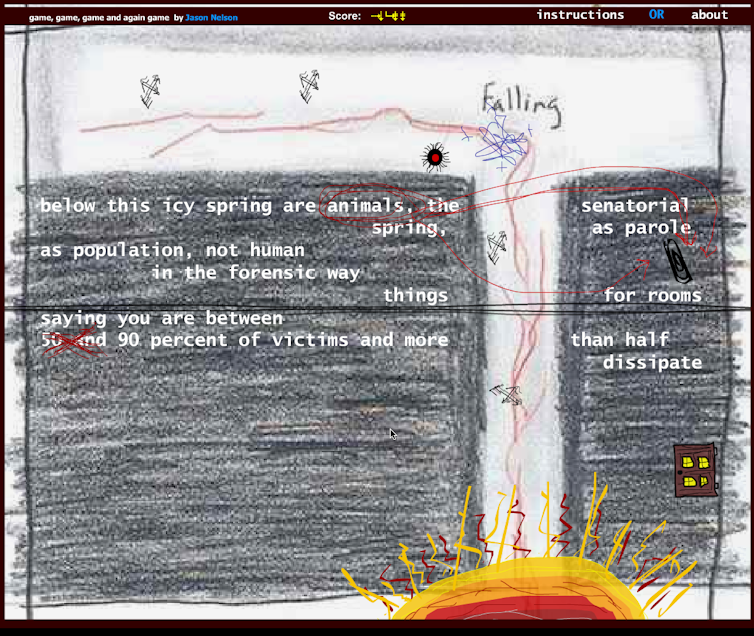

Queensland digital poet Jason Nelson has created a number of works that fuse these two modes. One is called game, game, game, and again game, which Nelson describes as “a digital poem, retro-game, an anti-design statement, and a personal exploration of the artist’s changing worldview lens”. The work disrupts commercial video game design with the player not striving for a high score – but instead moving, jumping, and falling through an excessive, disjointed, poetic atmosphere.

elmcip.net

The emergence of virtual reality games, such as Half-Life: Alyx, has also met with poetry.

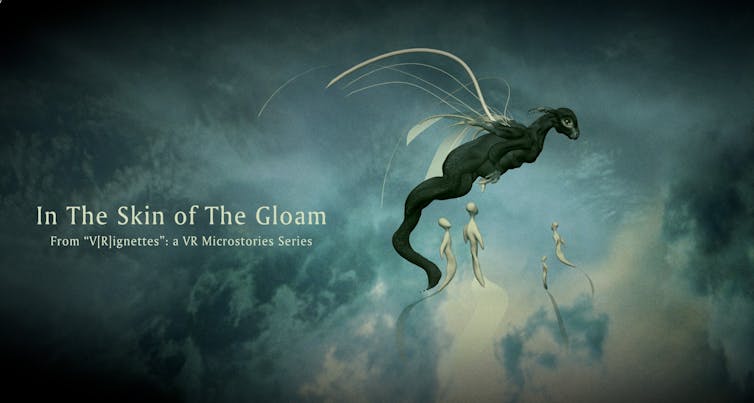

Australian digital artist Mez Breeze’s V[R]ignettes is a virtual reality microstory series. The audience can experience this work by donning a virtual reality headset or viewing it in 3D space in browser. Each V[R]ignette combines poetic text, 3D models, and atmospheric sound design. The reader (or user) can navigate by clicking on the “Select an annotation” bar at the bottom of the screen, or simply look around in 3D space and freely explore the work.

elmcip.net

5. Coded messages

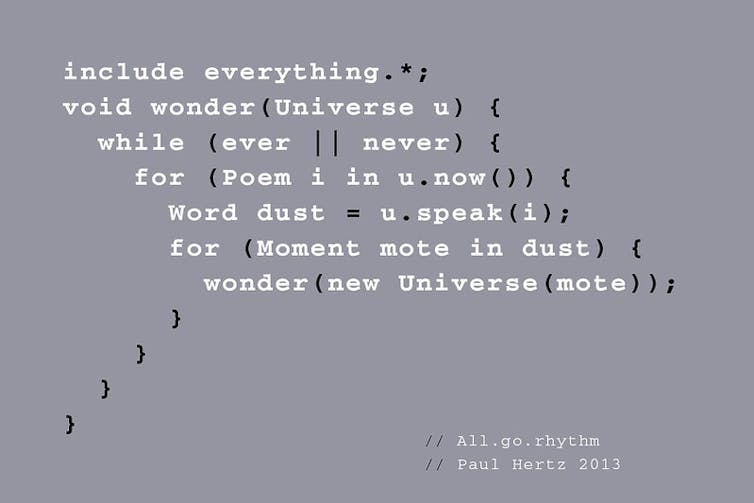

Code poetry is a genre that combines classical poetry with computer language.

Code poems, such as those compiled by Ishac Bertran in the print collection code {poems}, do not require a computer to exist. However, they do use computer languages, so to comprehend the poem one must be able to read computer code.

Like so many untranslatable Russian and Chinese poems, these works require a knowledge of the original language to be appreciated.![]()

Ignotus the Mage/flickr, CC BY-SA

David Thomas Henry Wright, Associate Professor, Nagoya University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.