The link below is to an article that looks at the role of Little Free Libraries in the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-08-20/little-free-libraries-in-the-time-of-covid

The link below is to an article that looks at the role of Little Free Libraries in the coronavirus pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-08-20/little-free-libraries-in-the-time-of-covid

Rachel Hadas, Rutgers University Newark

Pondering the now no-longer Dixie Chicks – renamed “The Chicks” – Amanda Petrusich wrote in a recent issue of the New Yorker, “Lately, I’ve caught myself referring to a lot of new releases as prescient – work that was written and recorded months or even years ago but feels designed to address the present moment. But good art is always prescient, because good artists are tuned into the currency and the momentum of their time.”

That last phrase, “currency and momentum,” recalls Hamlet’s advice to the actors visiting the court of Elsinore to show “the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.” The shared idea here is that good art gives a clear picture of what is happening – even, as Petrusich suggests, if it hadn’t happened yet when that art was created.

Good artists seem, in our alarming and prolonged time (I was going to write moment, but it has come to feel like a lot more than that), to be leaping over months, decades and centuries, to speak directly to us now.

Some excellent COVID-19-inflected or anticipatory work I’ve been noticing dates from the mid-20th century. Of course, one could go a lot further back, for example to the lines from the closing speech in “King Lear”: “The weight of this sad time we must obey.” Here, though, are a few more recent examples.

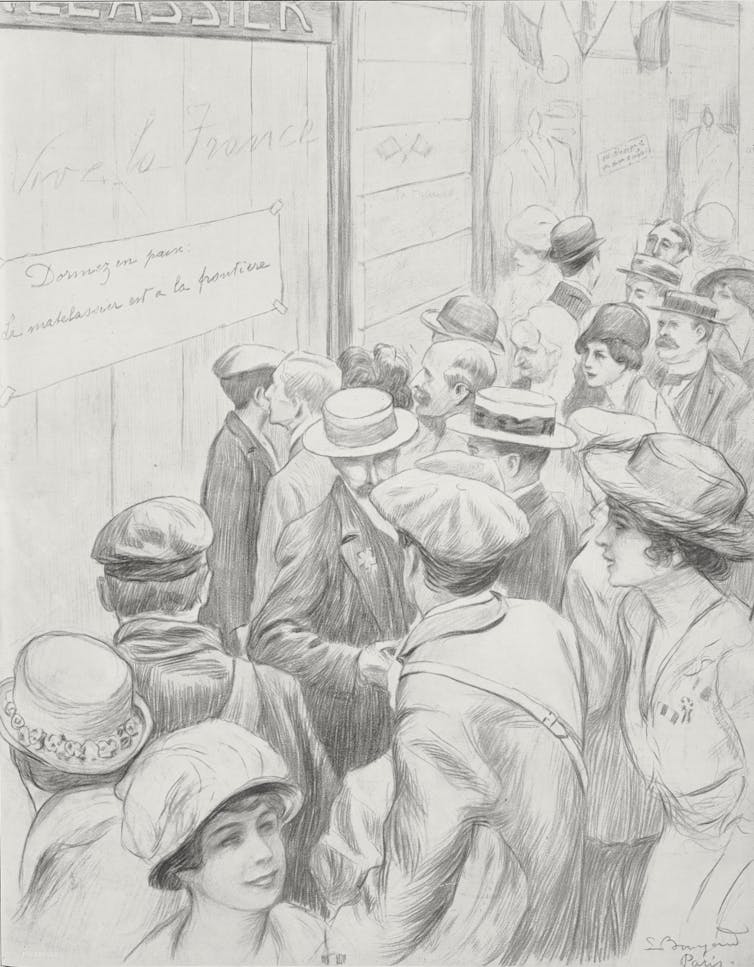

Marcel Proust’s “Finding Time Again,” an evocation of wartime Paris from 1916, strongly suggests New York City in March 2020: “Out on the street where I found myself, some distance from the centre of the city, all the hotels … had closed. The same was true of almost all the shops, the shop-keepers, either because of a lack of staff or because they themselves had taken fright, having fled to the country, and left the usual handwritten notes announcing that they would reopen, although even that seemed problematic, at some date far in the future. The few establishments which had managed to survive similarly announced that they would open only twice a week.”

I recently stumbled on finds from the 1958 edition of Oscar Williams’ “The Pocket Book of Modern Verse” – both, strikingly, from poems by writers not now principally remembered as poets. Whereas a fair number of the poets anthologized by Williams have slipped into oblivion, Arthur Waley and Julian Symons speak to us now, to our sad time, loud and clear.

From Waley’s “Censorship” (1940):

It is not difficult to censor foreign news.

What is hard to-say is to censor one’s own thoughts,-

To sit by and see the blind man

On the sightless horse, riding into the bottomless abyss.

And from Symons’ “Pub,” which Williams doesn’t date but which I am assuming also comes from the war years:

The houses are shut and the people go home, we are left in

Our island of pain, the clocks start to move and the powerful

To act, there is nothing now, nothing at all

To be done: for the trouble is real: and the verdict is final

Against us.

Dipping a bit further back, into Henry James’ “The Spoils of Poynton” from 1897, I was struck by a sentence I hadn’t remembered, or had failed to notice, when I first read that novella decades ago: “She couldn’t leave her own house without peril of exposure.” James uses infection as a metaphor; but what happens to a metaphor when we’re living in a world where we literally can’t leave our houses without peril of exposure?

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

In Anthony Powell’s novel “Temporary Kings,” set in the 1950s, the narrator muses about what it is that attracts people to reunions with old comrades-in-arms from the war. But the idea behind the question “How was your war?” extends beyond shared military experience: “When something momentous like a war has taken place, all existence turned upside down, personal life discarded, every relationship reorganized, there is a temptation, after all is over, to return to what remains … pick about among the bent and rusting composite parts, assess merits and defects.”

The pandemic is still taking place. It’s too early to “return to what remains.” But we can’t help wanting to think about exactly that. Literature helps us to look – as Hamlet said – before and after.![]()

Rachel Hadas, Professor of English, Rutgers University Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that considers how to safely share books during the coronavirus pandemic – how to disinfect books, etc.

For more visit:

https://bookriot.com/how-to-disinfect-books/

The link below is to an article that looks into the importance of bookshops in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.readitforward.com/authors/the-importance-of-bookstores-during-the-pandemic/

Irene Gammel, Ryerson University

We rarely associate youth literature with existential crises, yet Canada’s youth literature offers powerful examples for coping with cultural upheaval.

As a scholar of modernism, I am familiar with the sense of uncertainty and crisis that permeates the art, literature and culture of the modernist era. The modernist movement was shaped by upheaval. We will be shaped by COVID-19, which is a critical turning point of our era.

Societal upheaval creates a literary space for “radical hope,” a term coined by philosopher Jonathan Lear to describe hope that goes beyond optimism and rational expectation. Radical hope is the hope that people resort to when they are stripped of the cultural frameworks that have governed their lives.

The idea of radical hope applies to our present day and the cultural shifts and uncertainty COVID-19 has created. No one can predict if there will ever be global travel as we knew it, or if university education will still to be characterized by packed lecture halls. Anxiety about these uncertain times is palpable in Zoom meetings and face-to-face (albeit masked) encounters in public.

So what can literature of the past tell us about the present condition?

Consider Canadian author L.M. Montgomery, a master of youth literature. In her books, Montgomery grapples with change. She provides examples of how youth’s visions and dreams shape a new hopeful future in the face of devastation. I have read and taught her novels many times. However unpacking her hope-and-youth-infused work is more poignant in a COVID-19 world.

Her pre-war novel Anne of Green Gables represents a distinctly optimistic work, with a spunky orphan girl in search of a home at the centre. Montgomery’s early work includes dark stories as subtexts, such as alluding to Anne’s painful past in orphanages only in passing. Montgomery’s later works place explorations of hope within explicitly darker contexts. This shift reflects her trauma during the war and interwar eras. In a lengthy journal entry, dated Dec. 1, 1918, she writes, “The war is over! … And in my own little world has been upheaval and sorrow — and the shadow of death.”

COVID-19 has parallels with the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed more than 50 million people and deepened existential despair. Montgomery survived the pandemic. In early 1919, her cousin and close friend Frederica (Frede) Campbell died of the flu. Montgomery coped by dreaming, “young dreams — just the dreams I dreamed at 17.” But her dreaming also included dark premonitions of the collapse of her world as she knew it. This duality found its way into her later books.

Rilla of Ingleside, Canada’s first home front novel — a literary genre exploring the war from the perspective of the civilians at home — expresses the same uncertainty we feel today. Rilla includes over 80 references to dreamers and dreaming, many through the youthful lens of Rilla Blythe, the protagonist, and her friend Gertrude Oliver, whose prophetic dreams foreshadow death. These visions prepare the friends for change. More than the conventional happy ending that is Montgomery’s trademark, her idea of radical hope through dreaming communicates a sense of future to the reader.

The same idea of hope fuels Montgomery’s 1923 novel Emily of New Moon. The protagonist, 10-year-old Emily Byrd Starr, has the power of the “flash,” which gives her quasi-psychic insight. Emily’s world collapses when her father dies and she moves into a relative’s rigid household. To cope, she writes letters to her dead father without expecting a response, a perfect metaphor for the radical hope that turns Emily into a writer with her own powerful dreams and premonitions.

Nine decades later, influenced by Montgomery’s published writings, Jean Little wrote an historical novel for youth, If I Die Before I Wake: The Flu Epidemic Diary of Fiona Macgregor. Set in Toronto, the book frames the 1918 pandemic as a moment of both trauma and hope. Twelve-year old Fiona Macgregor recounts the crisis in her diary, addressing her entries to “Jane,” her imaginary future daughter. When her twin sister, Fanny, becomes sick with the flu, Fiona wears a mask and stays by her bedside. She tells her diary: “I am giving her some of my strength. I can’t make them understand, Jane, but I must stay or she might leave me. I vow, here and now, that I will not let her go.”

A decade later, Métis writer Cherie Dimaline’s prescient young adult novel The Marrow Thieves depicts a climate-ravaged dystopia where people cannot dream, in what one of the characters calls “the plague of madness.” Only Indigenous people can salvage their ability to dream, so the protagonist, a 16-year-old Métis boy nicknamed Frenchie, is being hunted by “recruiters” who are trying to steal his bone marrow to create dreams. Dreams give their owner a powerful agency to shape the future. As Dimaline explains in a CBC interview with James Henley, “Dreams, to me, represent our hope. It’s how we survive and it’s how we carry on after every state of emergency, after each suicide.” Here, Dimaline’s radical hope confronts cultural genocide and the stories of Indigenous people.

Radical hope helps us confront the devastation wrought by pandemics both then and today, providing insight into how visions, dreams and writing can subversively transform this devastation into imaginary acts of resilience. Through radical hope we can begin to write the narrative of our own pandemic experiences focusing on our survival and recovery, even as we accept that our way of doing things will be transformed. In this process we should pay close attention to the voices and visions of the youth — they can help us tap into the power of radical hope.![]()

Irene Gammel, Professor of Modern Literature and Culture, Ryerson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mayurika Chakravorty, Carleton University

In the early days of the coronavirus outbreak, a theory widely shared on social media suggested that a science fiction text, Dean Koontz’s 1981 science fiction novel, The Eyes of Darkness, had predicted the coronavirus pandemic with uncanny precision. COVID-19 has held the entire world hostage, producing a resemblance to the post-apocalyptic world depicted in many science fiction texts.

Canadian author Margaret Atwood’s classic 2003 novel Oryx and Crake refers to a time when “there was a lot of dismay out there, and not enough ambulances” — a prediction of our current predicament.

However, the connection between science fiction and pandemics runs deeper. They are linked by a perception of globality, what sociologist Roland Robertson defines as “the consciousness of the world as a whole.”

Read more:

Apocalyptic fiction helps us deal with the anxiety of the coronavirus pandemic

In his 1992 survey of the history of telecommunications, How the World Was One, Arthur C. Clarke alludes to the famed historian Alfred Toynbee’s lecture entitled “The Unification of the World.” Delivered at the University of London in 1947, Toynbee envisions a “single planetary society” and notes how “despite all the linguistic, religious and cultural barriers that still sunder nations and divide them into yet smaller tribes, the unification of the world has passed the point of no return.”

Science fiction writers have, indeed, always embraced globality. In interplanetary texts, humans of all nations, races and genders have to come together as one people in the face of alien invasions. Facing an interplanetary encounter, bellicose nations have to reluctantly eschew political rivalries and collaborate on a global scale, as in Denis Villeneuve’s 2018 film, Arrival.

Globality is central to science fiction. To be identified as an Earthling, one has to transcend the local and the national, and sometimes, even the global, by embracing a larger planetary consciousness.

In The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin conceptualizes the Ekumen, which comprises 83 habitable planets. The idea of the Ekumen was borrowed from Le Guin’s father, the noted cultural anthropologist Arthur L. Kroeber. Kroeber had, in a 1945 paper, introduced the concept (from Greek oikoumene) to represent a “historic culture aggregate.” Originally, Kroeber used oikoumene to refer to the “entire inhabited world,” as he traced back human culture to one single people. Le Guin then adopted this idea of a common origin of shared humanity in her novel.

Many medical science fiction texts depict diseases afflicting all of humanity which must put up a unified front or perish. These narratives underscore the fluid and transnational histories of diseases, their impact and possible cure. In Amitav Ghosh’s 1995 novel, The Calcutta Chromosome, he weaves an interconnected history of malaria that spans continents over a century, while challenging Eurocentricism and foregrounding the subversive role of Indigenous knowledge in malaria research.

The epigraph quotes a poem by Sir Ronald Ross, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist credited with the discovery of the mosquito as the malaria vector:

Seeking His secret deeds

With tears and toiling breath,

I find thy cunning seeds,

O million-murdering Death.

Pandemics are by definition global. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, noting that “[p]andemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly. It is a word that, if misused, can cause unreasonable fear, or unjustified acceptance that the fight is over, leading to unnecessary suffering and death.”

COVID-19 has forced billions into social isolation and continues to wreak havoc on an unprecedented global scale. Eerily similar photographs of masked faces, PPE-clad front-line workers and deserted downtowns emerged from every corner of the world.

However, a pandemic is not global merely in its spread — one needs to harness its globality to counter and eventually defeat it. As Israeli historian Yuval Harari notes, in the choice between national isolationism and global solidarity, we must choose the latter and adopt a “spirit of global co-operation and trust”:

What an Italian doctor discovers in Milan in the early morning might well save lives in Tehran by evening. When the U.K. government hesitates between several policies, it can get advice from the Koreans who have already faced a similar dilemma a month ago.

Regarding Canada’s response to the crisis, researchers have noted both the immorality and futility of a nationalistic “Canada First” approach.

Read more:

Canada must act globally in response to the coronavirus

Clearly, a nation cannot insulate itself from the deleterious effects of the pandemic by closing its hearts and borders. Tightening immigration can temporarily stanch the flow of people, but the virus, like the “million-murdering death,” is treacherous in its border-defying agility. Presently, as many nations experience a resurgence of nationalism and exclusionary policies of walls and borders, the pandemic is a harsh reminder of the lived reality of our transnational interconnectedness.![]()

Mayurika Chakravorty, Instructor, Department of English and Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies (Childhood and Youth Studies), Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kate Douglas, Flinders University and Kylie Cardell, Flinders University

We teach English at university. Our weekly engagements include navigating unnerving plot twists, falling in and out of love with iconic characters, and evaluating the complexities of language and genre.

Reading challenges how we think. Each week, in English classes, we explore some of the most significant issues and representations affecting various historical periods and cultures.

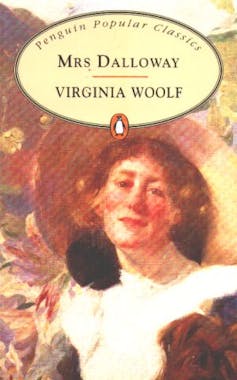

In the first semester, our reading list included classic works of literature that deal with themes including mental illness and psychological as well as physical isolation: Charlotte Perkins-Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

Then COVID-19 happened.

News reports began circulating on what professors were reading for refuge during the pandemic. An article in the New Yorker pondered why “anxious readers” might be soothed by Mrs Dalloway. This is a text that, in the past, has seen students request trigger warnings for its of “examination of suicidal tendencies” which “may trigger painful memories for students suffering from self-harm”.

Read more:

When literature takes you by surprise: or, the case against trigger warnings

Our teaching suddenly moved online, which created an even more unsettling set of conditions. We were teaching literary texts representing various kinds of trauma to students coping with a range of new (or exacerbated) issues due to sudden loss of employment, social disconnection, anxiety and fear.

Would reading these difficult texts prove to be a solace for our students, a timely example of the social role of literary storytelling, or a trauma all of its own?

Great stories move and they challenge. They draw attention to diverse social and cultural issues and to the transformative potential of empathy. But they can also be difficult and there are a range of reasons why.

The challenge might be intellectual. Or the text confronting on a psychological or emotional level.

A lot of literature is perceived as perpetuating racist stereotypes. Until quite recently, a good deal of canonical literature excluded the perspectives of women. This is something Woolf has written extensively about and that we can see at work in Mrs Dalloway. Part of her novel’s radicalism is its transgressive (for its era) narrowness of scope: a day in the life of a woman.

And of course, there are themes in literary texts that are in themselves inherently challenging or traumatic: war, racial violence, and misogyny are staples in Shakespeare’s plays.

In identifying difficult literature, the goal posts shift: what was confronting to past generations may not remain true for current readers. So too, what was acceptable to readers of a certain era may no longer be acceptable in the 21st century.

Universities have seen an escalation of interest in content and trigger warnings. Viewpoints have run at both ends of the extreme. Content warnings are either coddling the minds of the “snowflake generation”; or one step away from censorship. Others consider warnings as essential in protecting students from psychological harm.

As literature scholar Michelle Smith notes, it seems widely accepted a lecturer should give a warning before showing a graphic visual scene. However, the argument trigger warnings should accompany written literature that represents difficult or challenging subject matter has been met with more scepticism and opposition.

This places a great deal of responsibility on teachers to decide where to draw the line.

Teachers face the ambitious balance of wanting to protect our students from representations that might be too difficult and trigger unwanted emotional responses, alongside a desire to expose students to complex representations, and histories — for instance of inequality, discrimination, racism and sexism.

Read more:

If you can read this headline, you can read a novel. Here’s how to ignore your phone and just do it

We use the term “trauma texts” to explore how new literary subjects and voices have emerged in the 21st century. Trauma texts reveal literature’s potential for direct and active political and cultural engagement. When we take these texts into the classroom, we ask students to accept difficulty into their lives (if they can), and to witness complex lives and histories in nuanced, critically engaged ways.

Teaching in the time of COVID has re-energised these ongoing debates. For instance, there is an opportunity to recognise (with renewed vigour) how a reader’s individual experience shapes how they approach a particular literary text. We have developed new understandings of how literary texts operate in moments of great cultural or social upheaval.

In our research and practice we have found many positive outcomes when we teach difficult texts in university English. Our students appreciate the texts we teach address recognisable real-world problems.

These books offer opportunities for readers to show empathy, witness injustice and reflect on the ethics of representation. They offer skills (critical reading and thinking, debate, negotiation) that are transferable to diverse work contexts. They come to understand the value of literature (broadly conceived), and the wide cultural and political influence it may have.

Research has shown reading difficult texts with students requires care, and an awareness of how to approach content and trigger warnings. As life narrative theorist Leigh Gilmore reminds us, when we bring trauma texts into the literary classroom, we should teach as if someone in the room has experienced trauma.

The classroom needs to be a safe space.

In teaching difficult texts, it is a reasonable expectation we provide information (in advance) to students regarding any difficult content. We need to open a dialogue between student and teacher and this needs to be maintained throughout the semester so we can offer ongoing support.

Read more:

What my students taught me about reading: old books hold new insights for the digital generation

As well as empowering our students, this approach provides us with an opportunity to reflect, dynamically, on why we want to teach these texts.

In previous research we have argued that in English, we want to encourage students to confront new ideas and to be challenged by what they read. This is integral to the university experience. We are asking students to be generous readers who have the capacity to look inward and outward.

Now, more than ever we need tools to read and respond to human experiences of crisis and pain. Reading difficult literature is one way by which the eternal and ongoing responsibility of humanism can be fulfilled.![]()

Kate Douglas, Professor, Flinders University and Kylie Cardell, Lecturer in English, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that looks at publishing in the midst of a global pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/how-the-publishing-world-is-staying-afloat-during-the-pandemic_n_5ec431c9c5b69985547b5a5b

In the previous post it was noted how difficult reading was to do in the current climate of anxiety and fear regarding coronavirus. However, the link below is to an article reporting on the surge in reading during the pandemic.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/15/research-reading-books-surged-lockdown-thrillers-crime

The link below is to an article that looks at why it’s so difficult to read a book at the moment.

For more visit:

https://www.vox.com/culture/2020/5/11/21250518/oliver-j-robinson-interview-pandemic-anxiety-reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.