BBC/Scott Free/FX Networks

Sally O’Reilly, The Open University

Our fascination with ghostly tales around Christmas time goes back thousands of years and is rooted in ancient celebrations of the winter solstice. In the depths of winter, pagan traditions included a belief in a ghostly procession across the sky, known as the Wild Hunt. Recounting tales of heroism and monstrous and supernatural beings became a midwinter tradition. Dark tales were deployed to entertain on dark nights.

Ghosts have been associated with winter cold since those ancient times. According to art historian Susan Owens, author of The Ghost, A Cultural History, the ode of Beowulf is one of the oldest surviving ghost stories, probably composed in the eighth century. This is the tale of a Scandinavian prince who fights the monster Grendel. Evil and terrifying, Grendel has many ghostly qualities, and is described as a “grimma gaest” or spirit, and a death shadow or shifting fog, gliding across the land.

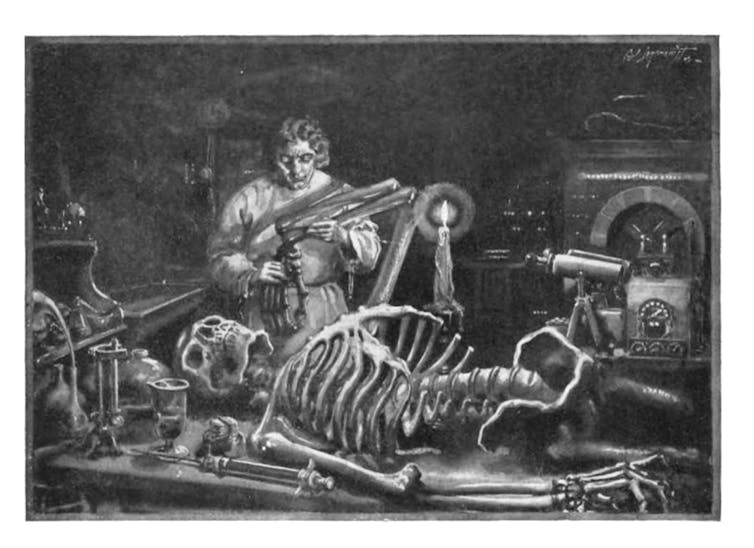

In 1611, Shakespeare wrote The Winter’s Tale, which includes the line: “A sad tale’s best for winter, I have one of sprites and goblins.” Two centuries later, the teenage Mary Shelley set her influential horror story Frankenstein in a snowy wasteland, although she wrote it during a wet summer in Switzerland.

The Victorians invented many familiar British Christmas traditions, including Christmas trees, cards, crackers and roast turkey. They also customised the winter ghost story, relating it specifically to the festive season – the idea of something dreadful lurking beyond the light and laughter inspired some chilling tales.

Both Elizabeth Gaskell and Wilkie Collins published stories in this genre, but the most notable and enduring story of the period was Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843). In this vivid and atmospheric fable, gloomy miser Ebenezer Scrooge is confronted first by the spirit of his dead business partner, Jacob Marley, and thereafter by a succession of Christmas ghosts.

Their revelations about his own past and future and the lives of those close to him lead to a festive redemption which has spawned a host of imitations and adaptations.

Dickens wrote the story to entertain, drawing on the tradition of the ghostly midwinter tale, but his aim was also to highlight the plight of the poor at Christmas. His genius for manipulating sentiment was never used to better effect, but perhaps the most enjoyable elements of the story are the atmospheric descriptions of the hauntings themselves – the door knocker which transforms into Marley’s face and the sinister, hooded figure of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

The tradition was further developed in the stories of M R James, a medieval scholar who published Ghost Stories of an Antiquary in 1904. His chilling Gothic yarns focused on scholars or clergymen who discovered ancient texts or objects with terrifying supernatural consequences.

Chilling tales

Typically, James used the framing device of a group of friends telling stories around a roaring fire. In the introduction to Ghost Stories he said: “I wrote these stories at long intervals, and most of them were read to patient friends, usually at the seasons of Christmas.”

Seminal stories in his oeuvre include Number 13, Oh Whistle & I’ll Come to You and A School Story. Like Dickens, James has been widely imitated and adapted, with Stephen King citing him as an influence. King’s The Shining certainly fits into to the genre of ice-bound chiller.

Christmas ghost stories morph into new forms as time passes, like ectoplasm. Spin offs of A Christmas Carol include Frank Capra’s 1946 classic It’s a Wonderful Life, in which the story is transposed to small town America, and the 2019 film Last Christmas, the tale of a dysfunctional young woman permanently dressed as a Christmas elf, ripe for Yuletide redemption. This contemporary version conveys messages about integration and the value of diversity.

A new, high-octane version of A Christmas Carol will be shown on TV this Christmas, written by Peaky Blinders creator Stephen Knight. And M R James’ Martin’s Close, the story of a 17th century murder and its supernatural outcome, has also been adapted for the small screen.

So it seems the atavistic desire to lose oneself in tales of the supernatural is still with us. Christmas ghost stories enhance our enjoyment of the mince pies and mulled wine, and the frisson of a paranormal tale offsets the “feel-good” festive spirit that might otherwise be cloying.

Some things never change – we still have a fear of the unknown, a yearning for what is lost and a desire to be secure. In an uncertain, fast-paced world, mediated through smartphones and social media, the seasonal ghost story is here to stay. The jolt of fear and dread such stories convey make the Christmas lights glitter even more brightly.![]()

Sally O’Reilly, Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.