Liu zishan via Shutterstock

Gavin Miller, University of Glasgow

Science fiction has struggled to achieve the same credibility as highbrow literature. In 2019, the celebrated author Ian McEwan dismissed science fiction as the stuff of “anti-gravity boots” rather than “human dilemmas”. According to McEwan, his own book about intelligent robots, Machines Like Me, provided the latter by examining the ethics of artificial life – as if this were not a staple of science fiction from Isaac Asimov’s robot stories of the 1940s and 1950s to TV series such as Humans (2015-2018).

Psychology has often supported this dismissal of the genre. The most recent psychological accusation against science fiction is the “great fantasy migration hypothesis”. This supposes that the real world of unemployment and debt is too disappointing for a generation of entitled narcissists. They consequently migrate to a land of make-believe where they can live out their grandiose fantasies.

The authors of a 2015 study stress that, while they have found evidence to confirm this hypothesis, such psychological profiling of “geeks” is not intended to be stigmatising. Fantasy migration is “adaptive” – dressing up as Princess Leia or Darth Vader makes science fiction fans happy and keeps them out of trouble.

But, while psychology may not exactly diagnose fans as mentally ill, the insinuation remains – science fiction evades, rather than confronts, disappointment with the real world.

The case of ‘Kirk Allen’

The psychological accusation that science fiction evades real life goes back to the 1950s. In 1954, the psychoanalyst Robert Lindner published his case study of the pseudonymous “Kirk Allen”, a patient who maintained an extraordinary fantasy life modelled on pulp science fiction.

Schnoodles blog, CC BY

Allen believed he was at once a scientist on Earth – and simultaneously an interplanetary emperor. He believed he could enter his other life by mental time travel into the far-off future, where his destiny awaited in scenes of power, respect, and conquest – both military and sexual.

Lindner explained Allen’s condition as an escape from overwhelming mental anguish rooted in childhood trauma. But Lindner, himself a science fiction fan, remarked also on the seductive attraction of Allen’s second life, which began to offer, as he put it, a “fatal fascination”. The message was clear. Allen’s psychosis was extreme, but it showed in stark clarity what drew readers to science fiction: an imagined life of power and status that compensated for the readers’ own deficiencies and disappointments.

Lindner’s words mattered. He was an influential cultural commentator, who wrote for US magazines such as Time and Harper’s. The story of Kirk Allen was published in the latter, and in Lindner’s book of case studies, The Fifty-Minute Hour, which became a successful popular paperback.

Critical distance

Psychology had very publicly diagnosed science fiction as a literature of evasion – an “escape hatch” for the mentally troubled. Science fiction answered back, decisively changing the genre in the following decades.

Amazon

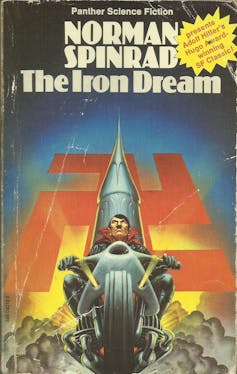

To take one example: Norman Spinrad’s The Iron Dream (1972) purports to reprint a prize-winning 1954 science fiction novel. The novel is apparently written, in an alternate history timeline, by Adolf Hitler, who gave up politics, emigrated to the US, and became a successful science fiction author and illustrator. A fictional critical afterword explains that Hitler’s novel, with its “fetishistic military displays and orgiastic bouts of unreal violence”, is just a more extreme version of the “pathological literature” that dominates the genre.

In her review of The Iron Dream, the now-celebrated science fiction author Ursula Le Guin – daughter of the distinguished anthropologist Alfred Kroeber – wrote that the “essential gesture of SF” is “distancing, the pulling back from ‘reality’ in order to see it better”, including “our desires to lead, or to be led”, and “our righteous wars”. Le Guin wanted science fiction to make strange the North American society of her time, showing afresh its peculiar psychology, culture, and politics.

In 1972, the US was still fighting the Vietnam War. In the same year, Le Guin offered her own “distanced” version of social reality in The Word for World is Forest, which depicts the attempted colonisation of an inhabited alien planet by a macho, militaristic Earth society intent on conquering and violating the natural world – a semi-allegory for what the USA was doing at the time in south-east Asia.

Wikipedia, CC BY

As well as repudiating the worst parts of the genre, such responses implied a positive model for science fiction. Science fiction wasn’t about evading reality – it was a literary anthropology which made our own society into a foreign culture which we could stand back from, reflect on, and change.

Rather than ask us to pull on our anti-gravity boots, open the escape hatch and leap into fantasy, science fiction typically aspires to be a literature that faces up to social reality. It owes this ambition, in part, to psychology’s repeated accusation that the genre markets escapism to the marginalised and disaffected.![]()

Gavin Miller, Senior Lecturer in Medical Humanities, University of Glasgow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.