The link below is to an article that offers a number of suggestions on how to read more books.

For more visit:

https://hbr.org/2019/04/8-ways-to-read-the-books-you-wish-you-had-time-for

The link below is to an article that offers a number of suggestions on how to read more books.

For more visit:

https://hbr.org/2019/04/8-ways-to-read-the-books-you-wish-you-had-time-for

The link below is to an article that takes a look at books about books.

The link below is to an article that takes a look at various modes of transport – planes, trains, ships, etc, and their place in books.

For more visit:

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/04/10/a-readers-guide-to-planes-trains-automobiles/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the history of product placement in books.

For more visit:

https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/4/8/18250031/book-product-placement-bulgar-connection-click-fic-shopfiction

The link below is to an article that takes a look at finding DNA in old books.

For more visit:

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/02/dna-books-artifacts/582814/

The link below is to an article that takes a look at the dos and donts of book promotion.

For more visit:

https://www.thebookdesigner.com/2019/02/book-promotion-do-this-not-that-february-2019/

The link below is to an article that looks at the top 100 books offered in libraries around the world.

For more visit:

https://www.oclc.org/en/worldcat/library100.html

shutterstock

Amy Wigelsworth, Sheffield Hallam University

An emerging genre of fiction in France is providing an unlikely brand of escapism. Growing numbers of French writers are choosing work as their subject matter – and it seems that readers can’t get enough of their novels.

The prix du roman d’entreprise et du travail, the French prize for the best business or work-related novel, is testament to the sustained popularity of workplace fiction across the Channel. The prize has been awarded annually since 2009, and this year’s winner will be announced at the Ministry of Employment in Paris on March 14.

Place de la Médiation, the body which set up the prize, is a training organisation specialising in mediation, the prevention of psychosocial risks, and quality of life at work. Co-organiser Technologia is a work-related risk prevention consultancy, which helps companies to evaluate health, safety and organisational issues.

The novels shortlisted for the prize in the past ten years reflect a broad range of jobs and sectors and a whole gamut of experiences. The texts clearly strike a chord with French readers, but English translations of these novels suggest many of the themes broached resonate in Anglo-Saxon culture too.

The prize certainly seeks to acknowledge a pre-existing literary interest in the theme of work. This is unsurprising in the wake of the global financial crisis and the changes and challenges this has brought. But the organisers also express a desire to actively mobilise fiction in a bid to help chart the often choppy waters of the modern workplace:

Through the power of fiction, [we] want to put the human back at the heart of business, to show the possibilities of a good quality professional life, and to relaunch social dialogue by bringing together in the [prize] jury all the social actors and specialists of the business world.

What better way to delve into this unusual genre than by reading some of the previous prize winners. Below are five books to get you started.

The first prize was awarded to Delphine de Vignan for Les heures souterraines. In this novel, the paths of a bullied marketing executive and a beleaguered on-call doctor converge and intersect as they traverse Paris over the course of a working day. A television adaptation followed, and an English translation was published by Bloomsbury in 2011. Work-related journeys and the underground as a symbol for the hidden or unseen side of working life have proved enduring themes, picked up by several subsequent winners.

Laurent Gounelle’s Dieu voyage toujours incognito, winner of the 2011 prize, takes us from the depths of the underground to the top of the Eiffel Tour, where Alan Greenmor’s suicide attempt is interrupted by a mysterious stranger. Yves promises to teach him the secrets to happiness and success if Alan agrees to do whatever he asks. This intriguing premise caught the attention of self-help, inspirational and transformational book publisher Hay House, whose translation appeared in 2014.

Read more:

Five books by women, about women, for everyone

Le liseur du 6h27 by Jean-Paul Didierlaurent, the 2015 winner, tells the story of a reluctant book-pulping machine operative. Each day, Ghislain Vignolles rescues a few random pages from destruction, to read aloud to his fellow-commuters in the morning train. The novel crystallises the fraught relationship between intellectual life and manual work.

It also illustrates the tension between culture and commerce, arguably at its most pronounced in France, where cultural policy has traditionally insisted on the distinction between cultural artefacts and commercial products. The Independent review of the English translation describes the book as “a delightful tale about the kinship of reading”.

Slimane Kader took to the belly of a Caribbean cruise ship to research Avec vue sous la mer, which claimed the 2016 prize. His hilarious account of life as “joker”, or general dogsbody, is characterised by an amusing mishmash of cultural references: “I’m dreaming of The Love Boat, but getting a remake of Les Misérables” the narrator quips. The use of “verlan” – a suburban dialect in which syllables are reversed to create new words – underlines the topsy-turvy feel.

Unfortunately, there’s no English version as yet – I imagine the quickfire language play would challenge even the most adept of translators. But translation would help confirm the compelling literary voice Kader has given to an otherwise invisible group.

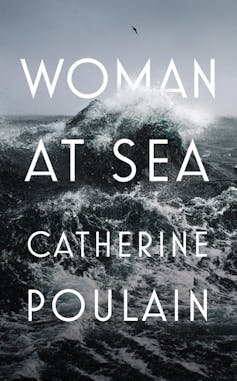

Catherine Poulain’s Le grand marin, the 2017 winner, is a rather more earnest account of work at sea. The author draws on her own experiences to recount narrator Lili’s travails in the male-dominated world of Alaskan fishing.

Le grand marin (the great sailor) is ostensibly the nickname Lili gives to her seafaring lover. The relationship is something of a red herring though, as the overriding passion in this novel is work. But the English title perhaps does Lili a disservice – she is less a floundering Woman at Sea, and more the true grand marin of the original.

This year’s shortlist includes the story of a forgotten employee left to his own devices when his company is restructured, a professional fall from grace in the wake of the Bataclan terrorist attack, and a second novel from Poulain, with seasonal work in Provence the backdrop this time.

The common draw, as in previous years –- and somewhat ironically, given the subject matter –- is escapism. We are afforded either a tantalising glimpse into the working lives of others, or else a fresh perspective on our own. English readers will be equally fascinated by French details and universal themes – and translators’ pens are sure to be poised.![]()

Amy Wigelsworth, Senior Lecturer in French, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sally O’Reilly, The Open University

My happiest times in childhood were spent reading the books of E. Nesbit, C.S. Lewis and Joan Aiken. Preferring to read in hidden corners where nobody could find me, I immersed myself completely in these stories and believed utterly in their magic, even attempting to enter Narnia via the portal of my grandmother’s wardrobe. As an adult, I still call myself a passionate reader, but sometimes feel as if I’ve lost my way compared to my childhood self. I buy vast quantities of books, talk about books, read as many as possible, sometimes even write them – but it’s not often I find that same pure immersion in an imagined world which has been such a lasting inspiration.

Celebrations like World Book day promote children’s reading and remind us all of the pleasures of a good book. Many of us make resolutions to read more, but these days there’s increasing pressure to read the “right” thing. The adult world presents a constant temptation to turn every activity into a competitive sport, and reading is no exception: it is beset with targets, hierarchies and categorisations. We guilt-read chick-lit and crime, skim-read for book groups and improvement-read from book prize shortlists.

Underpinning this is a relentless quest for self-improvement, demonstrated by the popularity of reading challenges, in which readers set themselves individual book consumption targets. On Good Reads, some participants have modest goals, others aim for as many as 190 in the year, which translates to 15.8 books a month, 3.6 a week or just over half a book each day. Impressive? Maybe, but others are reading even faster. One journalist recently embarked on a seven day social media detox and read a dozen books in that time. It’s a far cry from my days with Mr Tumnus.

This raises a fundamental question: why do we read at all? Do we want to enjoy books, or download them into our brains? Are we so obsessed with being able to tick a book title off a check-list that we risk forgetting that reading is a physical and emotional activity as well as an intellectual one? The perceived benefits of reading are often given more attention than the experience itself: campaigners tend to stress its utilitarian value and research findings that it increases empathy and even life expectancy.

But the reading experience is important. A sure sign of loving a book is slowing down when you come to the final pages, reluctant to leave the world it creates behind. As the UK reading agency puts it, “in addition to its substantial practical benefits, reading is one of life’s profound joys”. Children seem to know this intuitively, and engage fully with a story, often to the exclusion of all else. They are demanding, honest readers, more interested in what happens in a tale and where it takes them than whether it’s a Carnegie prize-winner.

As an adult, it is possible to recapture that immersive involvement with a book. What we need is the opportunity to focus entirely on the words, and a willingness to ignore stress-inducing challenges and targets. When I was writing my second novel I lived in Barcelona for a year, day-job free. During that time I read just six books, one of them Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent. At a recent writing retreat, I spent two hours a day reading Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. I engaged completely with these novels, forgetting the outside world, and they have stayed with me, their characters and plot twists vivid and familiar when other books, read hurriedly in snatches amid distractions, have faded from my mind.

I’m not alone in seeing the value of immersive, non-competitive reading. In a recent Guardian article, author Sarah Waters admitted to feeling out of the loop when current writing is discussed. Asked which book she is “most ashamed not to have read” (a telling phrase), she responded, “Anything people are currently raving about. I’m a slow reader, and I read old books as often as new ones, so I always feel like a hopeless failure when it comes to keeping up with brand new titles”.

There are already advocates of slow living, and a cultural shift toward slowing down life’s pace, savouring experience and rediscovering human connection. Perhaps it is time for this to encompass reading too. 184,000 books are published each year in the UK alone, and we’re not going to make much of a dent in that pile even if we read 12 books a week. Indeed, no matter how fast we read, the vast majority of books will remain unknown to us. If there is one skill that adult readers can usefully learn from children, it is that of reading purely for pleasure.![]()

Sally O’Reilly, Lecturer in Creative Writing, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The link below is to an article that reports on books, women and relationships. It is one of those articles I regard as nonsense, still, make up your own mind.

For more visit:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2019/feb/11/shelf-policing-how-books-and-cacti-make-women-too-spiky-for-men

You must be logged in to post a comment.